0

There’s an old saying about defecating and eating and not doing both in the same place. It is usually applied to interpersonal relations but serves just as well for industrial ones. And it is particularly relevant to mining. Certainly we don’t want to mine directly upstream of water intake sites, blast into rock near dense human settlements or leave scarred sites unrehabilitated. But as the scramble for increasingly scarce resources intensifies and the price of energy escalates, our axiom becomes increasingly untenable. Material flows are intensifying as their travel distances are shortening. With resource extraction, separation and containment are becoming less and less viable.

Offsetting the damage that mining does in one area by compensating with another less-disturbed site — which suggests that a landscape is composed of interchangeable pixels — is making it even harder. As the world effectively shrinks we may well have to eat, draw water and live where our waste ends up. Indeed in many ways we urbanites already are. Why shouldn’t this be a good thing? Cities have long been accruing refined products and are poised to deliver higher recycling yields than they currently are. We need to rewrite the equation so that cities — rather than being the distant instigators and, increasingly, victims of mining — are at the center of the metabolic loop.

1 Minerals

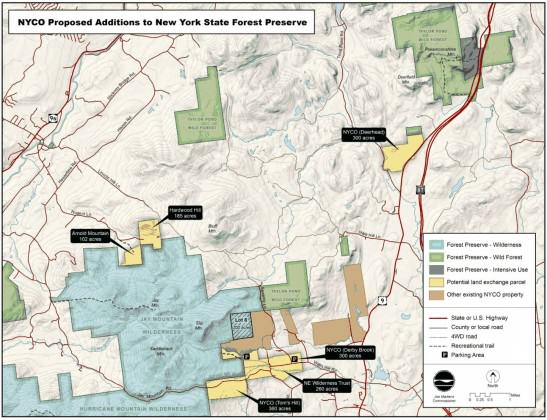

In the last local election in New York State, in November 2013, the question of whether to allow mining in an upstate forest preserve was put to the voters, including those in downstate — and potentially downstream — New York City. This made me happy. Even if some 400 km away, having a say in what happened in the far north was poetic justice since the distant State government had long held sway over local issues within New York City borders. (In fact some contend that the State government has long been ‘mining’ the City by spending less than 10% of the City’s tax revenue on City-related concerns.) It was also the first time I remember being able to directly vote on an environmental issue.

One of six on the ballot, Proposal Five was to amend a portion of the State Constitution to allow mineral extraction on roughly 1 km2 of land within Adirondack Park. Adopted in 1894, that portion of the State Constitution protected the 25,000 km2 Adirondack Park as off limits for sale or lease. Second to the higher-profile Mayoral election, all six Proposals were hidden on the back of the ballot like the throwaway songs on the ‘B side’ of a vinyl record. (20 per cent of voters didn’t even bother to flip it over. In New York City, 40 per cent of voters ended up abstaining on the referenda.) Still, I was sure New York’s voters would reject it.

Though it was the only Proposition on which New York City disagreed with the rest of the state, the measure narrowly passed with 53% of votes in favor of constitutional amendment. I was tempted — as I often am — to cast bad design as the villain. (The election in the State of Florida in 2000 illustrates the spectacular fiasco that poorly designed ballots can create.) But the culprit in this election was probably far more banal: simple ignorance. As a result NYCO Minerals, a private corporation, will extract wollastonite — a fairly anodyne mineral conventionally used in ceramics, plastics and asbestos replacement — from within a protected area.

Some ‘yes’ voters’ consciences may have been assuaged by the Proposal’s offset arrangement whereby an equivalent amount of land outside the current preserve would be substituted for the piece surrendered within. But New York State may be setting a more ominous precedent. This will be the first ever land swap within Adirondack Park — the largest park in the contiguous US, roughly the size of Albania or Rwanda — for private commercial profit. If NYCO Minerals were to go out of business the extracted land might not be returned to the public trust. In an age of global resource grabs and trade-offs with sometimes catastrophic consequences, the Adirondack mining expansion is relatively small scale. Still, it provides a fascinating lens through which to view the rural-urban continuum and it touches on the wider issues of tradeoffs between economy and environment, geopolitics and offsets.

Edward McClelland writes that ‘[a]n industrial city follows the same life cycle as a prizefighter or a prostitute. Its native beauty, the freshness of its earth and water, the youth and strength of its people, are used up and discarded’. Whereas downstate New York City remains a global financial capital, upstate New York State — like most of the Rust Belt that extends west across the Great Lakes — has never fully recovered from the loss of its manufacturing base. It is easy to understand why the region would seek to attract new jobs. On the other hand, if one doesn’t have a personal (and direct) stake in the economic gains, it is also easy to criticize prioritizing short-term economic gains for more dubious long-term environmental health. As it turns out, the new NYCO mine is expected to support just 100 jobs. In Essex County, where the mining site is located, 65% of voters supported Proposal Five (37% of some 26,000 eligible voters voted in Essex County), where conservatives outnumber liberals 2 to 1. That support — and general turnout — declined with distance to a low of 29% in remote New York City (24% of some 4.6 million eligible voters voted in New York City, where liberals outnumber conservatives 6 to 1).

While not one of the sexier rare earth minerals famed for their cool performance under high-heat conditions, wollastonite is nonreactive and bright. Second only to China in global production, the US extracts all of its wollastonite from two existing mines in the New York Adirondacks. The mines never sleep, operating 24/7 until the day they are tapped out and closed. One is reaching the end of its life and the land swap now allows NYCO to replace it with another. Increasingly wollastonite is being used as a performance-enhancing additive in concrete, which is now the second-most used resource in the world behind water itself. For the world’s most rapidly urbanizing areas access to concrete is essential. The wollastonite from the new mine may well end up deposited in the new skyscrapers of expanding cities around the world. Perhaps even in New York City itself, which anticipates a net gain of more than half a million residents by 2030.

In 2012 NYCO’s parent company was acquired by a minerals conglomerate in Athens that controls more than 100 mines in 20 countries, representing a diversification of supply and dispersal of risk. Environmental offsets such as the one represented by this land swap suggest that we can neutralize the sins we make in one area by compensating for them in another. Applied spatially, offsets treat land as an undifferentiated field of pixels, any of which could be swapped for another. But of course the effects of land and habitat degradation cannot be easily contained. And the false equivalency of ‘here for there’ distracts from the wider issues of land fragmentation and watershed degradation. Yet, in the ‘iTunes’ mentality of the early 21st century, New York State’s voters seemed content to see this story as two micro-targeted areas of interest in ignorance of the interrelated whole surrounding them.

2 Water

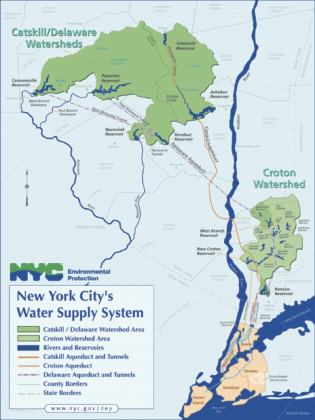

As it turns out, New York City is not actually part of the same watershed as the NYCO mines. Though the Hudson River also originates in the Adirondacks, the new Adirondack mining site is drained by a watershed that ultimately flows northward to the St Lawrence River, just downstream of Montreal. New York City’s vaunted tap water comes from another watershed, the Delaware-Catskill, which ultimately empties out further south near Philadelphia. Still, the themes of economy vs. environment and pixilated offsets have been playing themselves out over the wider politics of the US.

It has been said that upstate New York was the victim of its own ingenuity. In response to demands of the New York City printing industry, a Buffalo engineer more or less invented air conditioning in 1902. Air conditioning spread rapidly across the hotter, drier southern US, making the naturally mild climate and plentiful water supply of the northern Great Lakes region less of an advantage. Over the next decades, then, a great many factories left the north for the weaker labor and environmental regulations of the south. The fastest growth in the US still persists in the Sun Belt states. However, long forgotten upstate New York and the rest of the Rust Belt may have the last laugh if recent, record draughts in the Sun Belt prove more than a passing exception. California is now experiencing the worst drought in 500 years. Traditional extraction-friendly states like Texas and Oklahoma are seeing no better. The Executive Director of the Associate of California Water Agencies said that ‘[his] industry’s job is to try to make sure that these kind of things never happen. And they are happening.’

In West Virginia mining-related water troubles have been plaguing some 300,000 residents around the city of Charleston since early January when 20,000 litres of 4-methylcyclohexane methanol (MCHM) seeped out of storage tanks of Freedom Industries into the Elk River, just upstream of the water intake for the region. Exposure to MCHM in the local tap water has caused headaches, nausea skin irritation and difficulty breathing. Though the chemical has long been used in the processing of coal mined from the surrounding mountains, its human and environmental effects have never been thoroughly tested. In response to criticisms that the State was not doing enough to provide water and mitigate public health risk, the Governor simply said ‘[i]t’s your decision […] if you do not feel comfortable, don’t use it.’

Faced with multiple lawsuits over the Elk River spill, Freedom Industries filed for bankruptcy. There were other, less successful attempts to pick up and move on. While the tap water prohibition was still in effect the local water company allegedly attempted to provide untainted water in trucks on a point-by-point basis. The problem was the source of that water: the same Elk River, two km downstream from the chemical spill site. Either they did not understand or hoped no one else would notice that, where water is concerned, a polluted site cannot so easily be substituted for a non-polluted one. An increasingly dispersed scramble for diminishing supply is driving some increasingly desperate attempts to access resources where deposits are costly to access and rife with side effects. Extraction at this scale and intensity is seriously calling into question whether containment and offsets can actually work.

3 Oil and gas

Mining and water supply in New York State remain fairly well regulated, but what does potentially threaten New Yorkers’ water supply is the specter of hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as ‘fracking’. Use of the procedure is accelerating as much of the world’s low-hanging fruit, in terms of energy, disappears. Injecting high-pressure chemicals, water and sand into deep rock strata can liberate otherwise difficult-to-access places. But it is also premised on the gauzy hope that the desired substances — and only the desired ones — will be released. In fact, side effects not infrequently include ground water contamination of ground water, fresh water depletion — especially in the drought-afflicted areas of the Great Plains — air pollution and the migration of gases and hydraulic fracturing chemicals to the surface.

Proponents contend that it is safe when properly executed. Yet there remains so much that is uncontrollable and, frankly, unknown. And when potential profits exceed the litigation costs of possible environmental disaster, we are digging ourselves into a hole that is both spatially and metaphorically deeper than we have bargained for. Fracking represents a kind of three-dimensional pixellization in which chemicals are injected underground, often across vast areas and beneath settlements under the shaky assumption that its effects — whether contamination, tectonic shift or others — will not percolate beyond the target area. Nevertheless, widespread complaints in four US states (Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and West Virginia) suggest its effects are far from contained. In one viral example, a North Dakota man who lives in a fracking zone has posted an online video of him lighting his tap water on fire.

Until now, fracking has been banned in New York State. However, the ban is currently under review and many civil society organizations worry that intense industry lobbying may pressure Governor Cuomo. A new energy plan recently issued by the State does not include fracking as part of its long-term strategy, though it remains agnostic on the issue as a whole. But the Governor’s wider decision has yet to be announced, perhaps before November 2014. There is concern about the potential effect on the Delaware-Catskill watershed: if the state’s fracking ban were lifted, would New York City forfeit its waiver of the national water filtration requirement?

Until now, fracking has been banned in New York State. However, the ban is currently under review and many civil society organizations worry that intense industry lobbying may pressure Governor Cuomo. A new energy plan recently issued by the State does not include fracking as part of its long-term strategy, though it remains agnostic on the issue as a whole. But the Governor’s wider decision has yet to be announced, perhaps before November 2014. There is concern about the potential effect on the Delaware-Catskill watershed: if the state’s fracking ban were lifted, would New York City forfeit its waiver of the national water filtration requirement?

Two weeks ago we saw the environmental impact assessment for the Keystone XL pipeline that would increase the capacity to transport oil from Canadian fields to the US Gulf Coast for shipping. Like the NYCO minerals mine, the lifespan of the existing pipeline is near its end and expanded fracking is raising transport demand. But while a revised route has Keystone XL circumventing the fragile Nebraska Sand Hills, 400 km of it would still cross the highly superficial 450,000 km2 Ogallala Aquifer that supplies water to more than 2 million people. The report takes the shockingly cynical position that since climate-damaging fracking would essentially be taking place anyhow, the pipeline might as well be built. As we double down on our unsustainability, Godfrey Reggio’s film Koyaanisqatsi comes immediately to mind. But what is troubling about this movie is that it is so beautiful we almost forget to be alarmed by its wider message. Clearly it is ‘Life Out of Balance’, but the spectacle and sheer kinetic energy of so much production and consumption is dazzling. I wonder whether we are complacent or just bedazzled by it all. Or both?

1* Garbage

Interestingly, local environmental advocacy groups were somewhat divided on the merits (or evils) of the NYCO land swap. National environmental groups such as the Sierra Club joined Protect the Adirondacks in opposing it because of the precedent established by swapping land for private profit. On the other hand, Adirondack Council and Adirondack Mountain Club believe the 100 jobs and 7 km2 of forest land in exchange make it worthwhile. NYCO Minerals, which will operate the new wollastonite mine in the Adirondacks, has a record of restoring former mining scars to a modicum to habitat recovery. But, as past attempts have shown, a multi-storey hole in the ground is a drastic change and recovering mixed-growth, biodiverse habitat takes many human generations; far beyond the extremely narrow window of opportunity we have to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. But we are running out of time and land, and the metabolic circle is tightening.

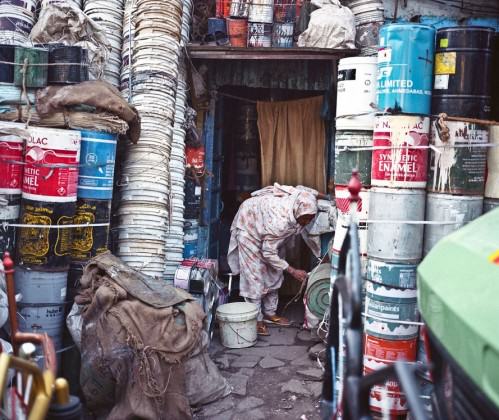

Consumption in population-heavy areas often instigates the rural mining that comes back to haunt those same areas in the form of contaminated water and food supply. Urban areas are usually seen as both the perpetrators and victims of unsustainable extraction. But they could be heroes, if their consumption literally fueled itself. Turning waste into inputs allows us close the loop on material flows. Whereas mineral ores have accrued over many millennia, cities often accrue valuable deposits over mere decades. The substances extracted and refined elsewhere are ‘redeposited’ into the buildings, landfills, sewers and other infrastructural systems of the city. In The Economy of Cities Jane Jacobs wrote about the city as a ‘waste-yielding mine’. By transforming that which is challenging and dangerous (and in any case difficult to contain), such as sulfur dioxide and fly ash, into a valuable asset.

Much earlier, and clearly inverting our earlier axiom, Paris achieved an elegantly circular metabolism of its food system whereby ‘night soil’ (i.e. human solid waste) was collected and redistributed as fertilizer to peri-urban farms. Since then, urban mining has reemerged in ways both intentional and informal. In many Rust Belt cities of the North American Great Lakes region, abandoned building stock that remains is frequently vulnerable to theft. Rather than going for typical consumer end products, renegade urban ‘miners’ strip the copper pipes and wiring from the buildings’ plumbing and electrical systems. Clearly this does not qualify as a ‘best practice’, but it signifies the increasing value seen in urban material deposits.

McClelland writes ‘[a]fter a car maker or a steel mill wears out a factory, extracts all the tax breaks a treasury will bear, and accumulates more obligations to its workers than the stockholders will bear, it flees town like a deadbeat husband, leaving a worn-out, exploited patch of land no one else will touch.’ Nevertheless, China has begun to invest in whole portions of cities in the US Rust Belt. For example, Toledo’s recently-obsolete, bargain-priced built infrastructure — and its easy fresh water supply — is a valuable asset to high-growth, limited-resource China. One high-growth economy is taking advantage, like a hermit crab, of the unoccupied urban shell of another. On some level this may be speculation on temporarily undervalued urban space. But it also effectively represents an innovative form of mining of post-industrial urban detritus.

Other more formal ways have been widely touted for their ability to transform problems into solutions. A number of cities including New York have begun generating power from methane emitted by landfills. A few such as Singapore have taken to purifying and transforming waste water into drinking water. Other cities are looking to generate power from the waste water that they collect and consolidate, 30% of the energy embedded in which can be readily reused. Most common, in any case, is the recycling of e-waste for more common and rare earth metals. The informal settlement of Dharavi, in Mumbai, continues to exemplify that cities are mines as profitable as conventional ones in rural areas, and they favor a more granular approach suited to SMEs. The continued obstacles of toxicity and child labor are formidable, but with better environmental and worker safety standards they can also provide work that is more decent.

The elephant in the room, or course, is energy consumption. Continued development is predicated — as it always has been — on a continuous supply cheap energy. But existing sources of minerals, water, oil and gas can only be extracted at an increasingly untenable financial and environmental cost. Cities can at least help with relative decoupling of growth from energy consumption and reduce energy demands in transport and building sectors (which are already responsible for approximately two-thirds of energy consumption globally). Shared infrastructure that reduces per capita demand. Material flows analyses are being undertaken by MIT and others. These analyses aim to account for all inputs, transformations and sinks generated through the city-regions’ production, distribution and consumption systems.

In the city, however, we are not necessarily faced with the binary of environment or jobs. Here we can have both if unwanted outputs become desirable inputs by exploiting cities’ highly concentrating infrastructural systems. ‘[City] mines will differ from any now to be found because they will become richer the more and the longer they are exploited. The law of diminishing returns applies to other mining operations: the richest veins, having been worked out, are gone forever. But in cities, the same materials will be retrieved over and over again. New veins, formerly overlooked, will be continually opened. And just as our present wastes contain ingredients formerly lacking, so will the economies of the future yield up ingredients we do not now have’ (Jacobs). Eldorado may not be a distant, legendary city of dazzling gold, but rather– as Calvino painted — our very own city built of cast-off things, whose riches are hidden underfoot. We may as well be bedazzled by it all. But there’s no need for cynicism.

Andrew Rudd

New York

About the Writer:

Andrew Rudd

Andrew Rudd is the Urban Environment Officer for UN-Habitat’s Urban Planning & Design Branch in New York, where he leads substantive advocacy for the urban dimension of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (including the SDGs).

You hint at necessary technological advances for a new urban world. I would add that we have good technology that happens to be old that should fit in. For example, the main classroom building at my alma mater, Vermont Law School, boasts composting toilets. The toilets were a necessity because the village wastewater system would not have been able to handle the influx of new facilities had the architects used a water flush mechanism. The toilets do not smell, and do not pollute the river that runs through town just a few hundred yards from the building. As a bonus, they never fail to freak out urbanites.