Urban populations—and the associated concentration of livelihoods and assets in cities—continue to increase worldwide, thereby increasing exposure to hazards. Coupled with aging infrastructure and housing stock, this trend leads to an increase in vulnerability. And this vulnerability is compounded by climate-change driven storms, sea-level rise, and associated flooding and landslides. Such events are increasing year after year; still, governments avoid reducing existing risk because they prefer not to spend money on uncertain outcomes before a disaster, especially because such efforts remain invisible even if the risk materialises. Instead, there are plenty of certain and visible outcomes to spend money on: compensating people after they lose their homess and sources of income. Governments also choose not to spend resources on risk reduction because of the prevailing political-economy climate, which is curbing expenditure in the public sector. This means that new risk (in terms of both exposure and vulnerability) continues to accumulate at a rate higher than existing risk is being reduced by risk reduction and resilience strategies. Most alarmingly, the prevailing process of reconstruction of houses, infrastructure, and livelihoods after a disaster often reintroduces risk into livelihoods and the built environment. Why is this still happening?

The UN, practitioners, and risk management consultancies are doing a lot of good work on disaster risk reduction, including encouraging governments to invest in disaster risk reduction. But the participants in this work haven’t connected to the public debate that is happening about risk—they are disconnected. What can we do to connect them?

To answer the above questions, it is probably good to start with examples of some of the problems that whole cities, and certain sectors (e.g. education sector especially in poor neighbourhoods and urban slums) within cities, are facing worldwide. Below are a few such examples:

- The rapid growth of cities and the populations within them means that cities are expanding quicker than the ability of governments to plan them according to pre-designed urban master plans and land use plans. This makes the people and the infrastructure more susceptible to damage from weather-related hazards (e.g. storms, floods, sea-level rise, etc.) and other hazards (e.g. earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, landslides, etc.). Also, all cities have poorer neighbourhoods with aging infrastructure (sewers, rainwater drainage networks, etc.) that is becoming ineffective even without the additional pressures due to climate change. These poorer neighbourhoods tend to have high population density, with people living in cramped conditions, in old unsafe buildings, and sometimes in close proximity to hazardous polluting industries. Clearly, this is a disaster waiting to happen when the next storm or the next earthquake arrives! Everyone knows that! National and local governments know that, local businesses know that, international aid agencies and UN agencies should know that, and the people themselves most certainly know that! Yet rarely do we see these risks being reduced before a disaster! Why? This is a question that we must ask even if we don’t have a clear answer to it.

- The stock of school buildings varies widely in many countries, with some new buildings built to resist major earthquakes and other risks together with older school buildings designed and built decades ago. Often, such older buildings are crumbling without the help of an earthquake or a storm. Countries that have succeeded in improving safety in all their school buildings are countries that have adopted what is referred to as a National School Safety Programs (NSSPs) that takes a long-term view to safety in schools. NSSPs have been successfully adopted in Chile and New Zealand and are promoted in all OECD (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development) member countries. Yet in many countries, even including those ranked as middle as high income countries, an NSSP is not even on the agenda! Why? This is another question that we must ask!

- In our age of globalisation, economies and businesses in different continents are connected by complex supply chain dynamics wherein businesses in the USA depend on parts manufactured in Asia or Europe and vice versa. Businesses rely on the safe functioning of trade routes, including ports and canals, in order to ship and sell their commodities all over the world. If a trade route or a supply chain is interrupted somewhere, capital and investments will leave and not return. In such cases, local economies and livelihoods will be lost and investments wasted. Yet we still see a prevailing mentality of investments pouring into countries with a short-term view of maximising profits irrespective of the sustainability of these profits or the livelihoods producing them.

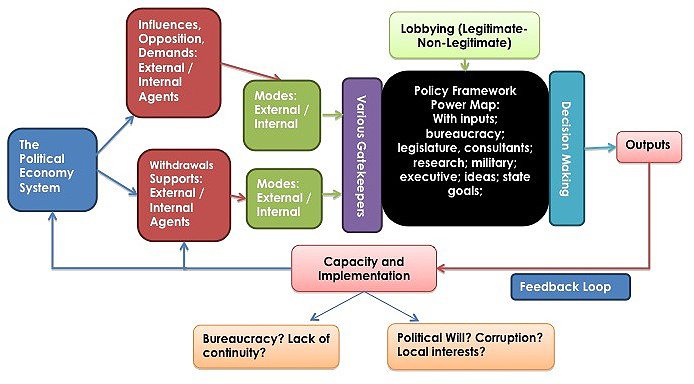

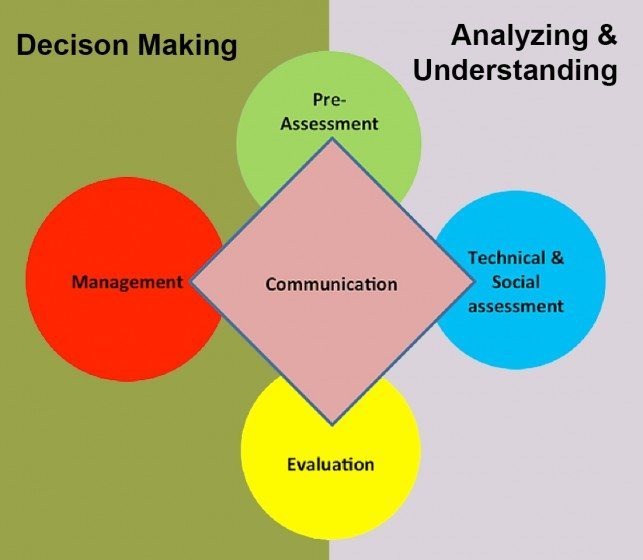

The answer to all of these questions—or, at least, the part of the answer which is often ignored—has to do with the way decisions are made regarding 1) accountability for the creation of risk, 2) what risks we decide to reduce or not reduce, 3) to what levels we reduce those risks, 4) where we get finances to reduce those risk or why we decide not to finance risk reduction, 5) who participates in all of the above decisions and who is excluded in terms of sectors (e.g. banking, industry, commerce, agriculture, natural scientists, social scientists, etc.), and 6) to what degree the decision making process is transparent, subject to scrutiny and accountability (for example: how often are officials held accountable if risk is not reduced or if risk is reintroduced after a disaster?). All of these aspects of decision making related to risk form what we call Risk Governance: how governments arrive at decisions on risk creation and risk reduction, as well as who is allowed to participate in the decision-making process.

It is only recently that we have recognised risk governance as an issue, and so more work needs to be done to rectify problems with risk governance. Improved risk governance is very important because it forms the missing link between the knowledge creation being pioneered by various practitioners, UN agencies, and aid agencies on the one hand and between governments who are ignoring the evidence and not acting on this knowledge on the other hand. Good risk governance will empower all affected people, sectors, and businesses to lobby for enhancing the accountability of decisions regarding risk construction, risk reduction, and risk reintroduction.

But let us first start from the beginning, or near the beginning, of one of the most important international initiatives to manage and reduce risks.

International frameworks and initiatives for disaster risk reduction, including risk governance

The Hyogo Framework for Action 2005 – 2015 (HFA) is a 10-year plan to make the world safer from natural hazards and was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in the Resolution A/RES/60/195 following the 2005 World Disaster Reduction Conference. The HFA set five Priorities for Action for reducing disaster risk between 2005 and 2015:

- Ensure that disaster risk reduction is a national and a local priority with a strong institutional basis for implementation.

- Identify, assess, and monitor disaster risks and enhance early warning.

- Use knowledge, innovation, and education to build a culture of safety and resilience at all levels.

- Reduce the underlying risk factors.

- Strengthen disaster preparedness for effective response at all levels.

The above priorities for action are meant to be implemented at national, local, and sectoral levels. In particular, their implementation at local levels was strengthened by the development of the Making Cities Resilient Campaign, launched by the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) in May 2010.

In analysing progress in the implementation of the HFA, the following challenges have been observed:

- More effort is needed to move from a culture of disaster management that focuses on responding to disasters after they occur to a culture of disaster risk management that prevents new risk from accumulating and reduces levels of existing risk before a disaster actually occurs.

- While significant effort has been directed at planning to respond to disasters and to prevent new risk from accumulating (partly through building codes and land use planning), more effort is required to reduce existing levels of risk. Even when strategies for disaster risk reduction are developed, they are not regularly transformed into policies with corresponding allocations of resources.

- Additional effort is needed in developing recovery strategies, policies, and plans a priori to ensure that reconstruction of livelihoods and the built environment in the wake of a disaster will not reintroduce risk. We can only avoid reintroducing risk by building back better. However, in many cases, in the wake of a disaster, the pressure to restore services and housing means that risk is created and transferred as a result of a reconstruction process that lacks the necessary scrutiny and participation of various stakeholders.

- Additional work is needed to understand how risk is constructed and transferred between sectors, which will in turn allow for much-needed enhancement of accountability for risk construction and transfer.

- Additional effort is required to engage more diverse stakeholders in disaster risk management activities, particularly in the most vulnerable sectors and communities.

- Capacity-building for local and national governments did not lead to the desired change in disaster risk reduction practices. It was concluded that change can only be effected by focusing on improving risk governance as defined above.

- In many cases, capacity-building and awareness-raising is driven by supply (e.g. by universities and research institutions, risk management consultancies, etc.) rather than demand and ignores the social, economic, and institutional factors contributing to vulnerability; instead, such efforts focus solely on natural and physical factors contributing to vulnerability.

- In many cases, too much emphasis is placed on natural factors (e.g. hazard frequency and severity, which are used to produce hazard area and hazard intensity maps) and physical factors (e.g. the physical state of the built environment, critical infrastructure, etc.). Notwithstanding the importance of the physical and natural factors, these alone do not complete our understanding of why vulnerability and risk accumulate (and are allowed to accumulate) and why they are (or are not) reduced. To do that, there is a need to examine the social (construction of risk in informal settlements, limited awareness, social capital), economic (financing disaster risk management from public and private investments, competing sectoral needs) and institutional (e.g. overlap in mandates, gaps in mandates, capacity shortages) factors contributing to vulnerability.

The above challenges are also reflected in The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030 (SFDRR), the successor instrument to the Hyogo Framework for Action, which was adopted at the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Sendai, Japan, on March 18, 2015. The SFDRR reviewed the progress of various states in the implementation of the HFA and identified the following challenges: the need for improved understanding of disaster risk; the need to strengthen disaster risk governance; the need for accountability for disaster risk management; the need to be better prepared to “Build Back Better”; the need for recognition of various stakeholders and their roles; the need for mobilization of risk-sensitive investment to avoid the creation of new risk; the need for resilience of health infrastructure, cultural heritage, and work-places; and the need for accountability for risk creation and the transfer of risk. Based on the above, the SFDRR proposed seven global goals, outcomes, and outputs and then identified the following four priorities for action over the coming 15 years, from 2015 up to 2030:

- Priority 1: Understanding disaster risk.

- Priority 2: Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk.

- Priority 3: Investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience.

- Priority 4: Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective responses and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction.

Gaps in risk governance

At this stage, as the SFDRR is being finalised and the monitoring framework and indicators agreed upon, it is useful to elaborate on some of the main governance gaps in the implementation of disaster risk reduction strategies and policies categorised under different headings below:

- Institutional governance gaps: very few countries worldwide have succeeded in establishing risk governance frameworks to provide checks and balances—in a transparent and participatory manner—throughout the risk management and reduction process.

- Science-based governance gaps: There is unanimous agreement on the need to improve the science/policy interface, particularly in view of the increased recognition of linkages with sustainable development and climate change. However, the “science” in the science/policy interface is often dominated by earth science and risk management consultancies addressing frequency and severity of natural hazards and/or by engineering consultancies addressing the vulnerability of the built environment and housing, including critical infrastructure. Therefore, often the social, economic, and institutional factors are missing from scientific assessments on vulnerability and risk. In many instances, this leads to “scientific” solutions being developed without addressing the social, economic, and institutional challenges and factors that have led to the accumulation of risk and vulnerability in the first place.

- Preliminary assessment governance gaps: In many cases, important solutions are not identified or are ignored at the risk framing stage, when the scope of hazards is identified and the qualitative and quantitative methodologies that may be used to assess risk are being selected. For example, as mentioned in the beginning of this article, in the education sector, best practice dictates the adoption of National School Safety Programs (NSSPs) that have proven to be an effective tool in preventing new risk from accumulating in school buildings and in reducing existing levels of risks. However, in many countries worldwide, NSSPs are not identified as a possible solution. A similar argument can be made for other critical infrastructure sectors (e.g. health, industry, energy, water, public sector buildings, and primary responding agencies). Indeed, in many instances, calls for identifying the financing gap—let alone securing the finances—required for ensuring the sustainable development and resilience of cities and sectors within them go unheeded.

- Comprehensive risk assessment governance gaps: Even though there is scientific evidence that extensive risk (risk that occurs regularly, such as the flood that happens every year due to average year rainfall and is not severe) significantly and disproportionately impacts vulnerable communities and livelihoods, leaving them more vulnerable to intensive risk (which happens rarely, such as the flood corresponding to the storm that happens once every couple of hundred years, but is more severe when it happens), the fact remains that most multi-hazard, vulnerability, and risk assessments continue to a) ignore extensive risk and b) assume that intensive risk happens in a vacuum rather than recognizing that it is superimposed on a socio-economic situation where people and communities allocate resources to address everyday needs and extensive risks (which feel more tangible because they are more frequent).

- Societal risk governance gaps: Very few countries and cities have mechanisms for carrying out both technical and societal risk assessments, which are important in case of substantial uncertainty associated with the frequency and severity of hazards or with the consequences of its occurrences.

- Risk evaluation governance gaps: The value of the tolerable and the unacceptable levels of risk should be determined by states and countries depending on their level of development and available financial resources. Setting values of tolerable and unacceptable risks inevitably involves setting a value on saving a human life. However, these decisions are too often made in an implicit, non-transparent manner or, perhaps even more worryingly, these decisions are knowingly or unknowingly delegated to private sector companies.

- Disaster loss data collation governance gaps: Loss of human lives, sources of income, and assets continues to be influenced by disaster-loss data collation practices that focus on compensation. This automatically implies that those communities that are living in informal housing or whose livelihoods are obtained from the informal sector will not be included in the loss collation exercise, as they are not considered eligible for compensation. However, especially because there is wider recognition of the need to identify and strengthen linkages with sustainable development and climate change, there is a need to widen the scope of disaster loss collation and analysis so it includes direct and indirect losses to livelihoods, lives, and economic sectors irrespective of eligibility for compensation. Furthermore, loss data, when available, is not dis-aggregated according to age, sex, ability, and social and economic backgrounds, making the analysis of factors affecting vulnerability more challenging.

- Recovery governance gaps: Few countries and cities have developed a priori recovery plans so that the reconstruction process will not reintroduce risks into the built environment, critical infrastructure, and livelihoods. Having a priori plans is particularly important when the reconstruction process is being financed using public debt for developments that are unsustainable. These will have to be paid for by future generations who will not reap the benefits of the unsustainable development.

- Financing risk reduction governance gaps: all countries and states have fixed budgets with competing sectors and stakeholders for resource allocation. There is a need to understand why certain strategies and policies for risk reduction are not being implemented, how the winners and losers are determined as a result of decisions being made regarding where public funds are directed, and the type of incentives given to the private sector.

- Governance gaps regarding the regulatory role of governments in disaster risk reduction: National and local governments are allocating resources for responding to disasters. More recently, through land use and building codes, amongst others, new risk is prevented from accumulating via sound investment and development decisions by both the private and public sectors. Through such decisions, governments are fulfilling part of their stewardship role of protecting people against external hazards. Currently, this role is not being completely fulfilled because existing risk is not being sufficiently reduced. In addition, governments are explicitly reviewing and refining mandates for disaster risk management to ensure they are capable of fulfilling their managerial role in disaster risk management. The main gap, however, is in the regulatory role of governments. Governments are required to protect people and sectors against risks created by other individuals and sectors. This was one of the main gaps in the HFA and therefore it is necessary to ensure that it is sufficiently addressed during implementation of the SFDRR. In turn, this requires us all to address the challenging task of understanding how risk is created by sectors and individuals and the manner in which it is transferred, legitimately or maliciously, to other sectors and individuals.

A proposed way forward

Risk management consultancies have vested interests in focusing on the natural and physical factors contributing to vulnerability. Other stakeholders, including insurance companies and contracting and construction companies, may have other vested interests related to risk transfer and recovery practices. Many practitioners are trying to balance these vested interests by calling for a risk governance process to manage all decisions and by producing evidence-based arguments showing the need for risk governance. However, these arguments produced by practitioners will not effect change unless they are taken on board by concerned and affected citizens and stakeholders who want to improve the environment in which we live.

Therefore, it is important for us—disaster risk management practitioners, urban designers, and others—to recognize that we must increase our efforts to ensure that we are providing the needed advice to decision makers. However, perhaps more importantly, we must also view our work as trying to act as the missing link: to inform the public debate that is taking place around disaster risk and resilience, thereby providing the public (the ultimate decision maker) with the scientific tools to carry out scientific, evidence-based lobbying to reduce disaster risk and improve resilience.

Fadi Hamdan

Beirut

About the Writer:

Fadi Hamdan

Fadi has more than 25 years of international experience in analysing the interaction between development, urbanism, disaster risk, climate change, conflict, and state fragility. Fadi cooperates with various companies, cities, and countries to protect people, assets, and the environment

1 Comment

Join our conversation