A review of the International Conference on the Economics of Happiness, held on September 3-5, 2015 in Jeonju, South Korea.

“We need to re-establish the link between city and land.”

At the opening ceremony of the Economics of Happiness conference, we were happily greeted with this statement from the event’s director, Dr. Helena Norberg-Hodge, who called for everyone present (governments, NGOs, activists, and local citizens) to re-establish the link between city and land, and in turn, as we understand, to use this link as a basis for how we go about our economic and social activities.

Norberg-Hodge called for all activists to be “big picture” activists, united by a shared vision for social and ecological wellbeing. “How do we get there?” she asked the audience “re-connect to others and re-connect to nature.”

It’s a sentiment that we’ve all seen echoing not only through activist circles, but also through professions from architecture and urban design to politics and law. Bringing individuals from such professions together, the Economics of Happiness is a global initiative, bolstered by the success of the recent film of the same name. Through the film and the parent nonprofit organization Local Futures, which Norberg-Hodge directs, it would seem that a global cultural phenomenon is slowly taking root in cities and communities around the world.

Global though it may be, Economics of Happiness is perhaps more appropriately described as a global collection of local initiatives, all of which are united by a shared vision rooted in things like compassion and connection. The conference was uplifting—as you might expect a conference on the Economics of Happiness would be—and filled with advice and success stories presented by speakers from the USA, UK, Japan, and South Korea.

Of particular interest to The Nature of Cities readers, the conference was supported largely by Jeonju city’s Mayor Seong Su Kim, who wants to use it as a blueprint for building a happy, sustainable city, one that looks at a more “useful” measurement than GDP and per-capita income in order to gauge the wellbeing of its citizens. Speakers chimed in to this effect through multiple viewpoints including law, industry, public service, and—perhaps most pervasively—the subjects were sprouting directly from the social and ecological ground in which they are planted.

“The roots of all our major problems are intertwined” noted Keibo Oiwa, author of Slow is Beautiful, and founder of Japan’s Sloth Club, a movement for slow living amidst one of the most fast paced countries in the world. By the acknowledgment that all of our problems are intertwined, we also come to see that the solutions, too, are intertwined.

As in nature itself, sharing one success broadly and across disciplines and borders, will ultimately lead to more success.

A common theme at the conference, Oiwa asked us to look to nature, saying that “Nature seems to know where to stop its growth and progress… how to take just enough”, further suggesting that the major deficiency in the way we think of and carry out “progress” is that this process is fundamentally disconnected from nature, from reality, and often from other people.

Oiwa’s philosophy also pushes us to see how re-connecting to nature and each other as the basis of our design and building process does not necessarily mean stopping progress.

All we have to do is look at the progress of nature itself for a case study, at how fast nature grows and re-generates and innovates; we can have a sustainable progress that is connected to and informed by nature, giving us amazing progress and beauty side by side.

Speaker Janelle Orsi took the concept of ‘connection’ from a social angle, giving a sharp yet witty critique of the “sharing economy.” A highly contested term in urban areas, the “sharing economy” is most often identified, ironically, with highly lucrative business models like Uber and AirBnB, which claim “sharing” as their philosophy.

Orsi, who is co-founder of the Sustainable Economies Law Center in Oakland, California, gave the conference attendees a different take on the meaning of a sharing economy, calling for us to look more deeply at what sharing means, and whether we can morally justify profiting wildly from others and still call it sharing.

The “real sharing economy”, Orsi says, is seen in projects such as community gardens, worker-owned businesses, car shares, and collaborations. She gave a convincing argument for a new local economy, one based on four levels of increasing scale: relationships (such as borrowing and sharing on a temporary basis), agreements (such as co-owning and space sharing), organizations (such as a food co-op), and universal systems of support (public transit, basic income, universal healthcare).

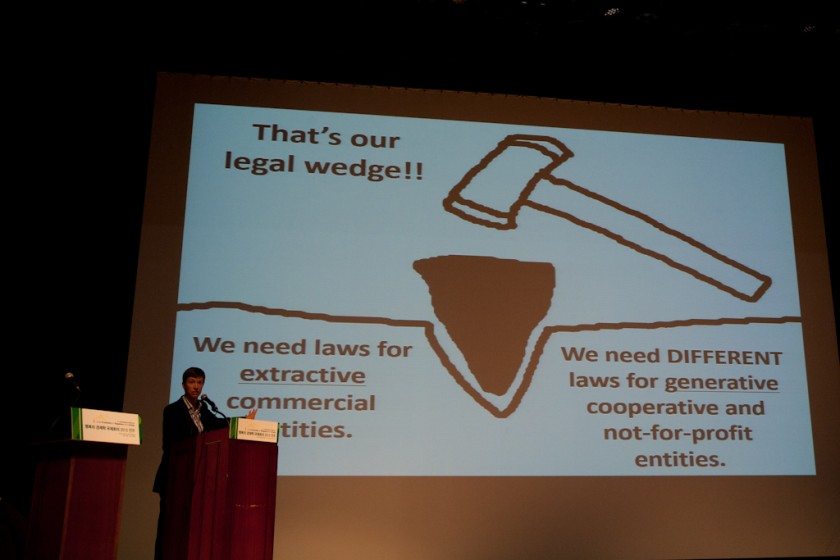

Being a lawyer by trade, Orsi is engaged with “fixing” the restrictive laws we find—perhaps most often at state and local levels—which prohibit a true sharing economy from emerging. “We need different laws and regulations”, said Orsi, suggesting a set of laws for what she calls “extractive” commercial entities, and a different set for “generative” entities like co-operatives and non profit organizations.

The intent is to be more restrictive on profit driven organizations, which tend to “extract” wealth from a local economy, and to be more encouraging for those organizations which generate wealth and wellbeing for the people.

Reflecting strongly the thoughts of the late economist E.F. Schumacher, another constant theme throughout most of the conference was the call to be small. Schumacher’s 1973 book, “Small is Beautiful”, continues to be a highly influential call for economic thinking which puts people and the environment as central concerns.

Smallness encourages better relationships between people and the environment, and better relationships between people and the environment give us a framework to take development actions that have sustainability and wellbeing built into their core. Schumacher’s concepts are statements of absolute simplicity and clarity at once.

Speaking to this point, Neil McInroy, from the U.K. based Centre for Local Economic Strategies, gave a plan to “bring the economy back home” by building out a full, diverse, and resilient local economy that merges “commercial, public, and social” economic sectors.

Perhaps most surprising was Jeonju’s Mayor Kim’s very sincere call to action for building a happy and sustainable city, much of it surrounding ecological and agriculture-related themes.

Mayor Kim, who was a huge champion of bringing the Economics of Happiness event to his city—and who insisted that the organizers make it an annual event going forward—gave a very daring strategy which, he noted, goes against the national agenda in South Korea. This is not easy territory for a South Korean mayor to tread, even in a mid-sized city like Jeonju.

One of Mayor Kim’s main points was ecology, where he highlighted efforts by the city to invest in local biodiversity, reforestation, and cutting river pollution. Of these, the call for biodiversity is one of the most critical, yet is only beginning to take form in public forums.

Mayor Kim might be happy to know, however, that such topics are well discussed here on TNOC:

- http://www.thenatureofcities.com/2014/11/30/urban-biodiversity-is-both-educational-and-public-awareness-challenge/

- http://www.thenatureofcities.com/2014/11/23/a-study-of-biodiversity-in-the-worlds-cities/

- www.thenatureofcities.com/2012/08/14/discovering-urban-biodiversity/

It’s good to see that biodiversity is now a major target for Mayor Kim and Jeonju City.

In the area of food and agriculture, Kim noted that only 10 percent of food consumed in Jeonju city is from local sources, and he made a call for the city to aim for food sovereignty.

Food sovereignty!

Those are big words, and the Mayor backed them up at least in part, by highlighting the establishment of a city “food charter” which will mandate the use of locally-produced organic foods in schools and city-government organizations. This is only a small gesture compared to what would need to happen for food municipal sovereignty, but the momentum is moving in the right direction.

How will the Mayor go about true food sovereignty? Rather than focusing on urban agriculture, the Mayor primarily pointed to focusing on the broad areas of agricultural land that he is fortunate to have surrounding the city.

Mayor Kim has a year to get to work before the next Economics of Happiness conference, and though none of us reading this are likely strangers to empty promises from political figures, in his corner, the Mayor had a good few hundred citizens in attendance at the conference and related workshops.

Immediately following the conference, there were local workshops, and the Mayor implemented a distributed network of small neighborhood support centers to deal with social economy and urban regeneration, instead of just having a central development office. Small is Beautiful.

Small, local, connected to the environment and to each other: it’s an enviable framework that is taking root both here in Jeonju, and in cities around the world where local governments and citizens are mobilizing to take local actions.

All of that local legwork could add up to some big global changes.

Patrick Lydon

San Jose & Seoul

About the Writer:

Patrick M Lydon

Patrick M. Lydon is an American ecological writer and artist based in Korea whose seeks to re-connect cities and their inhabitants with nature. He writes The Possible City series, is co-founder of City as Nature (Daejeon). He is an Arts Editor here at The Nature of Cities.

I wish that I had known about this conference. I am an expat who has lived in Korea for more than 15 years. I teach courses in globalization, futures studies, and intercultural communication at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. I have also worked with Dr. Park, Hyun-rhul on Heal-Being Culture in Korea. I believe that I would have enjoyed attending this conference. Anyway, it’s good to see the good works and I hope that in the future I will be able to attend.

As a City of Joondalup Councillor (http://www.joondalup.wa.gov.au – a local government located in Western Australia, near Perth) and a project coordinator (on a voluntary basis) organising community action to restore our local biodiverse coastal reserves and bushland parks (for example, http://www.porteouspark.org.au – a website created by one of the volunteer members of that particular group), I was pleased to see that a conference has been held to promote the connection of the city to the land. I am doing that in just one of many different ways that is possible, helping residents in my city to understand and appreciate their natural assets. Also, using grant money, I employ some community members (sometimes young people needing work experience) part-time under my supervision to do the more specialist tasks. The volunteer + part time contractor model helps us achieve great on-ground results together!