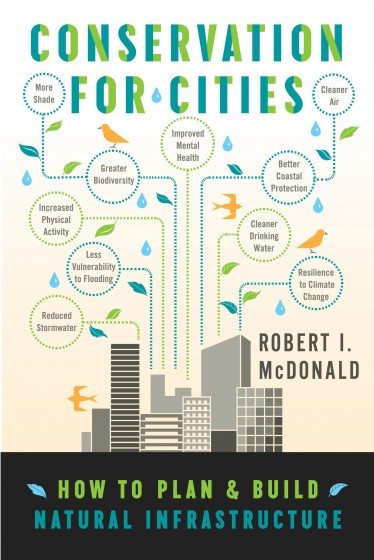

A review of Conservation for Cities How to Plan and Build Natural Infrastructure, by Robert I. McDonald. Island Press, Washington. 2015. ISBN: 9781610915236. 268 pages. Buy the book.

In Conservation for Cities, Robert I. McDonald seeks to “guide urban planners, landscape architects, and conservation practitioners trying to figure out how to use nature to make the lives of those living in cities better.” The book succeeds as an introduction to how a broad range of municipal services can be provided by ecological systems—both natural and man-made. It is a slim compendium, based on the Manual for Cities published by The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB 2011) program, and extends this manual by providing planning strategies, implementation guidelines and monitoring protocols.

In Conservation for Cities, Robert I. McDonald seeks to “guide urban planners, landscape architects, and conservation practitioners trying to figure out how to use nature to make the lives of those living in cities better.” The book succeeds as an introduction to how a broad range of municipal services can be provided by ecological systems—both natural and man-made. It is a slim compendium, based on the Manual for Cities published by The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB 2011) program, and extends this manual by providing planning strategies, implementation guidelines and monitoring protocols.

Following an overview of the ecosystem service concept and a planning framework for Conservation for Cities, ten chapters each focus on one ecosystem service. Each ecosystem service chapter begins with a short and compelling narrative case study that highlights an environmental problem and how ecosystem services have contributed to a solution. Quito, the second largest city of Ecuador, illustrates drinking water protection through source watershed protection by restoring the paramo—high altitude grasslands. France, the country that suffered the most fatalities in the 2003 European heatwave, demonstrates benefits of tree-shade for heat mitigation. Paris, France, experienced 142 percent higher mortality rates in August 2003, with different neighbourhood microclimates acting as a predictor of death rates—more shaded suburbs had lower death rates. Los Angeles children that participated in a Southern California health study highlight the positive effect access to parks can have on the health and wellbeing of children. The common thread that these stories illustrate is the power of working with nature instead of against it. Consistent organisation of these chapters provides ready access to the topics: how to map important services; common threats and common solutions; valuation of the natural infrastructure; implementation; and monitoring.

The ecosystem services selected for this book are arguably the most vital for enhancing the livability of cities. They range from stormwater protection and flood damage mitigation to the utilisation of tree-shade for heat mitigation and green spaces for physical and mental welfare. Dr. McDonald draws on his experience to include introductory technical information regarding how to measure and assess ecosystem services. Especially useful are his synopses of available tools for mapping, evaluating and analysing extant natural infrastructure. Tables on various software programs provide an at-a-glance summary of models used to value air and drinking water quality, coastal protection status, floodwater risk and stormwater services. Key data inputs and outputs identify how usable or appropriate a software program might be given available data, and highlights limitations of existing models or data sets. Some of the other chapters—particularly on drinking water protection, shade and air purification—illuminate well how natural systems can achieve these goals using measures and analyses comfortable for city engineers and planners. By contrast, it is in the most qualitative and complex areas—mental health and biodiversity—that this book is weakest; little justice is done to the complexity of the latter, in particular. Further still, the ecosystem services of food production and fibre provisioning are omitted entirely, although these are distinctly challenging topics for peri-urban areas.

While Conservation for Cities dwells on how to value (in quantitative terms) and use nature, it is disturbingly silent on a second stated concern—“how conservation actions can maintain or create natural infrastructure, ensuring and perhaps enhancing ecosystem service provision.” At the heart of asset planning—be those assets buildings, pipes, roads, or money—is creation, maintenance and renewal. With a few exceptions (for example, trees), the natural asset protection or management component of natural infrastructure is largely absent or underdone—which is notable if only because these elements are at the core of the term conservation. Regrettably, this introductory book misses the opportunity to emphasise and explicate the multiple benefits (or co-benefits) a particular element of natural infrastructure can provide.

In his overview, Dr. McDonald points out that “many conservation actions provide multiple ecosystem service benefits” and proceeds to ask “if it is the sum total of all co-benefits that should be considered, why is this book structured with each chapter considering a separate ecosystem service?” His answer is “for the simple reason” that most planning processes or pieces of legislation focus on one service. All the more reason a book like this could challenge traditional thinking, drawing out the potential value of these multiple opportunities in a discrete chapter, case study or diagrams. Mention is made here and there about co-benefits, but we fear they are easily lost in the welter of words focusing on the topic at hand.

In his closing chapter, Parting Thoughts, Dr. McDonald notes that although he has used utilitarian language to discuss ecosystem services because “these are often the terms on which important planning decisions are made,” there is another way “to frame conservation in cities to preserve or enhance ecosystem services: as actions to promote the common good,” concluding that “the new science and tools of ecosystem services merely allow us a clearer, more precise vision of what steps must be taken to preserve the common good.”

This is admirable stuff, but we offer a cautionary note. Utilitarian language may be appropriate in this context, but the dangers of discussing the use of ecosystems without a conversation about their protection or enhancement may be a focus on ‘using’ nature, with too little attention paid to the potential negative environmental impacts of this use or the consequences of unsustainable use. If we turn the focus solely to the component parts of ecosystem services, like clean air or drinking water, the ecosystem itself—a vibrant, dynamic interconnected system unique to a geographic place with living entities at its heart—simply drops out of the picture. That is not likely with the readers of TNOC. Yet it is something to keep in mind for readers with no background in natural resource management.

This book has an ambitious goal: to guide urban planners, landscape architects, and conservation practitioners in utilising natural infrastructure. This goal is one which more experienced practitioners may feel is under-delivered. Achieving brevity and breadth with such complex subject matter requires sacrificing depth, and we missed the provision of comprehensive references to topical material in a number of places. Guidelines for implementation and monitoring are generally advisory, considerably brief, and very high level.

To conclude, students, local government authorities and urban planning organisations as well as interested members of the general public will find this book helpful as an overview of the benefits a range of ecosystem services can provide for city living. Many of the chapter case studies are inspiring, showing how elegantly simple solutions, many of them involving protecting natural assets, can have a powerful impact in mitigating environmental problems and improving city livability.

The sting in the tail is that exactly how we might reproduce such examples, or incisively examine them, remains elusive. Such detail is not the province of this book, but it will have served its purpose if it takes readers further down an exploratory path.

Anna Backstrom and Laura Mumaw

Melbourne

You can support TNOC (and the book’s authors) by buying the book via this link.

About the Writer:

Laura Mumaw

Laura’s work, based in Melbourne, is in engaging communities with nature.

About the Writer:

Anna Backstrom

Anna is a Landscape Ecologist working throughout Victoria, Australia and a PhD student at RMIT University, Melbourne, researching urban biodiversity conservation.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation