Inequality is on the rise! Recent statistics published by Oxfam on the economy of the 1 percent show that the richest 62 billionaires own as much wealth as the poorer half of the world’s population. The report goes on to show that the wealth of the poorest half of the world’s population has fallen by a trillion dollars since 2010, a drop of 38 percent. This decrease occurred against an increase in the global population of around 400 million people. Meanwhile, the wealth of the richest 62 individuals has increased by more than half a trillion dollars, to $1.76 trillion U.S. dollars. The report concludes that the fight against poverty cannot be won until the inequality crisis is tackled.

I would add that the inequality crisis cannot be successfully tackled unless we tackle all the manifestations of inequality, not simply wealth and income inequality. We cannot reduce urban Inequality unless we fix inequality in exposure and vulnerability to disaster risk and inequality in the distribution of disaster losses.

How urban inequality shows itself

At the urban level, inequality takes different shapes and forms, including inequality in:

- Wealth and income

- Employment possibilities: legal vs. informal, safe vs. unsafe, healthy vs. hazardous, with or without health benefits, with or without child support, amongst others

- Infrastructure: (availability and quality of water, availability and quality of wastewater networks, availability and quality of road networks and public transportation

- Crime, law, and order: frequency of burglaries, frequency of violent crime, drug-related crime, frequency of crime against more vulnerable groups including women, children, the elderly, and the homeless

- Basic education and health services: in particular access to and quality of: primary education, secondary education, of university and higher education, health services and hospitals

- Housing: size and quality of housing, safety of housing, safety of land

- Vulnerability to risk

Why is inequality on the rise? Why aren’t all forms of inequality being recognized?

Before deciding on what needs to be done, we need to understand what has recently happened such that inequality is increasing at such rates. In this regard, it is important to recognize the recent rise of the interests of financial capital and the rentier sector versus industrial capital and other forms of productive economic activity. It is this dominance of interests, and the drive for quick profits, that is often leading to a degradation of existing infrastructure and to a lack of sufficient investment in the renovation of infrastructure. This trend is also leading to the real estate sector, and unchecked urban expansion, being a main driver of economic growth in many countries. Notwithstanding the importance of all these sectors to GDP growth, these are now acting as disaster-risk drivers that must be promptly addressed in order to reduce inequality.

What is currently being done?

Governments are increasingly recognizing the rise in this inequality worldwide. Similarly, UN and international donor agencies are also trying to reduce this inequality. However, due to the prevailing compartmentalized approach of developmental work, efforts to reduce the above forms of inequality are not sufficiently recognizing the inequality in the exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards and climate change, and the inequality in the disaster losses arising from them.

How does inequality in exposure and vulnerability to hazards manifest?

Inequality in exposure to and vulnerability to hazards manifests in different forms, including:

- Exposure of jobs, infrastructure, housing, and basic services to natural hazards and climate change risks.

- Vulnerability of jobs, infrastructure, housing, and basic services to natural hazards and climate change risks.

- Distribution of disaster losses (in jobs, infrastructure, housing and basic services) caused by natural hazards and climate change.

- Exposure, vulnerability, and distribution of disaster losses due to conflict.

How can urban inequality be reduced?

Urban inequality can only be reduced by first recognizing that a holistic approach is required. It is no longer acceptable to suppose that a compartmentalized approach can work. For example, efforts to improve the quality of health and education services should recognize the inequality in the vulnerability and exposure of school buildings. In addition, efforts to create more jobs in order to reduce unemployment and poverty must ensure that these jobs and livelihoods are resilient against natural hazards and climate change.

However, this can only be done once citizens recognize that they must scrutinize the implications of financial and economic policies that favour the real estate, rentier, and financial sectors at the expense of the job-rich pro-poor sectors, including industry and agriculture. For example, the following, but by no means exclusive, government decisions have direct implications on the exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards and potential losses from them:

However, this can only be done once citizens recognize that they must scrutinize the implications of financial and economic policies that favour the real estate, rentier, and financial sectors at the expense of the job-rich pro-poor sectors, including industry and agriculture. For example, the following, but by no means exclusive, government decisions have direct implications on the exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards and potential losses from them:

- Not providing safe, affordable land for housing inevitably implies that poorer families will build on unsafe land that is more vulnerable to natural hazards such as landslides, mudflows, and storm surges, among others. Failing to provide safe, affordable land for housing also leads to poorer families moving into the vicinity of hazardous polluting industries. In turn, this translates into a higher degree of direct and indirect losses.

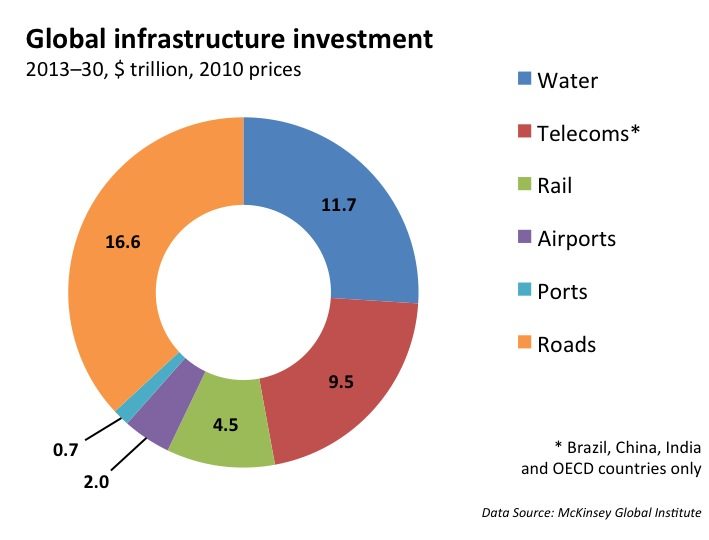

- Not investing in the retrofitting of infrastructure inevitably means that poorer neighborhoods, where infrastructure networks tend to be older and weaker, and where population concentration is higher, will be more exposed to weather related hazards, which are increasing in both frequency and severity due to climate change. It also implies that poorer neighborhoods will not receive the necessary prompt assistance by rescue and evacuation services. This trend should be contrasted against current estimates of an infrastructure gap reaching $57 trillion U.S. dollars, without accounting for sustainable development, which may lead to a larger gap.

- Not investing in rehabilitating slum neighborhoods, and providing land titles, inevitably leads to housing with high vulnerability to natural hazards, thereby explaining the high degree of fatalities in the wake of hazardous events.

- Not developing a national strategy for financing disaster risk management solutions often leads to the lack of availability of micro-finance and micro-insurance, thereby implying that the most vulnerable households, communities and livelihoods cannot invest in reducing risk or in insuring against disasters.

- Favouring reducing inflation, at the expense of reducing unemployment, inevitably leads to more poverty, which—as a main disaster-risk driver—leads to poorer households living on unsafe lands, unable to invest in resilient housing, and unable to find decent jobs to lift them from poverty and allow them to invest in building resilience.

- Favouring the rentier and real estate sector at the expense of the pro-poor, job rich, industrial, and agricultural sectors inevitably leads to higher unemployment, leaving millions unable to afford safe housing or to invest in building resilience.

It is these decisions that often lead to high degrees of inequality in terms of exposure, vulnerability, and disaster losses. Citizens and various stakeholders, including NGOs and various urban pressure groups, can address this inequality by 1) recognizing that it happens, 2) scrutinizing the decision-making process and the vested interests that lead to decisions being made, 3) tracing the decision-making process that leads to risk being constructed due to certain decisions, 4) tracing the transfer of new and existing risk between sectors, 5) forming alliances between NGOs, sectors, urban communities, and vulnerable stakeholders in order to lobby governments and big donors to recognize and address these issues. Only then will the aspirations of donor organizations such as the World Bank’s—We dream of a world without poverty—stop being a dream and become a reality!

Fadi Hamdan

Beirut

About the Writer:

Fadi Hamdan

Fadi has more than 25 years of international experience in analysing the interaction between development, urbanism, disaster risk, climate change, conflict, and state fragility. Fadi cooperates with various companies, cities, and countries to protect people, assets, and the environment

Hi Fadi, you make some excellent points and the link between inequality and disaster risk should be household in any analysis of vulnerability as a fist step to affecting change.

In addition to the points you already made I am wondering about your views on how unequal exposure to risk manifests itself differently in the different political economy scenarios (e.g. industrial/brics versus financial capital dominated economies, vs rentier economies) that influence urbanization and urban governance?

Thank you for this very informative piece of work! I have a couple of questions that I would like to share with you:

1- What can be different roles played by central governments, local authorities, national and international NGOs and private sector in addressing urban inequalities? especially as related to inequality in exposure and vulnerability to disaster risk and inequality in the distribution of disaster losses.

2- What needs to change in the donors’ approaches / mechanisms to funding poverty reduction initiatives that would result in less urban inequality?

3- Is urban inequality manifested in the same way across the humanitarian-to-development continuum or are there specific characteristics that stand out and would require distinct approach(es) to addressing them based on the different phases disaster management cycle?