How do you like roller coaster rides? I love them—provided that I am sitting in the operator’s cabin and not in one of the small, shaken carts frantically moving up and down. In two of my last posts, The Nurtured Golem: A Nantes Neighborhood Transforms Environmental Bad into Good, and Is There any Type of Urban Greenspace that Addresses the Rural-Urban Continuum? Urban Agriculture, I praised urban agriculture as the cornerstone that could help reconfigure more sustainable cities by bringing people together and, eventually, reshaping the whole urban fabric.

Let me be crystal clear: Community gardens, kitchen gardens, organic micro-farming, and rooftop farming are very positive for a city’s sustainability and for the well-being of its inhabitants. I am not trying to disparage urban agriculture. Quite the contrary, my intention is a kind of whistle blowing: to distinguish between the different types of urban agriculture and to denounce those which, under the disguise of promoting agriculture in the city, promote practices that are absolutely unsustainable.

Basically, urban agriculture is the practice of cultivating, processing, and distributing food in or around a village, town, or city. Although both are about growing edible plants in the city, we can distinguish between three very different categories, which share few things in common:

First are kitchen gardens and community gardens, as well as organic micro-farming characterized by collective or family type organization. These flourish at ground level of on rooftops. Second are parcels of conventional industrial farming land, which remain where urban growth incorporates farmlands into the urban fabric. This form is particularly pertinent for cities located in vine-growing or grain-growing regions. Third, is what has been described as “tree-like” skyscrapers for farming, a type of high-tech agriculture—in contrast with the two first categories, which can be considered low-tech—that is often associated with smart cities.

The new craze for urban agriculture, which began 20 years ago, primarily concerned organic micro-farming, and kitchen and community gardens, a type of agriculture that can enrich and transform the city positively and make it more sustainable. But it generated a sudden interest for urban agriculture in general, and drew the attention of many economic and political players, large building companies, architects looking for inspiration (and celebrity), and big farmers doing conventional farming. They generally did not have interest in bringing people together, or in fostering inclusiveness and ownership. Urban agriculture was a label used to sugarcoat the pill to maintain conventional farming in the city or to develop urban projects—like high-rise buildings—that otherwise would have been taken very badly by the people living in or on prospective sites.

Urban agriculture’s mania opened a window of opportunity to impose high-rise buildings or to turn intensive agriculture in the city “green”. All a sudden, concrete and glass towers became acceptable in places where not a single inhabitant would have accepted them before, provided that the buildings looked “green”. At the ground level, conventional urban farming became nice and acceptable, though it can generate nuisances such as dissemination of pesticides and fertilizers that have a negative impact on health and on the biodiversity in the city.

Those who greenwash conventional or high-tech agriculture in the city as sustainable mislead. It is deeply problematic, as I will show with two very different cases that are connected in one important way: the exposure to pesticides of city-dwellers living alongside fields cultivated under intensive conventional agriculture, and the potential destruction of the urban fabric by skyscrapers camouflaged in green.

Towers camouflaged in green

Let’s begin with the case of skyscrapers camouflaged in green, which, by the way, are paradigmatic of the problems that can be generated by mixing intensive agriculture with high-rise buildings. Have you never heard of these new architectures, which have been proliferating since the nineties in the wake of the Smart Cities movement? Tree-like skyscrapers, cultivating plants or breeding animals within tall greenhouse buildings or vertically inclined surfaces? The point of this farming laden with eco-technologies is to exploit synergies between the built environment and intensive—if not industrial—agriculture. Naturally, its promoters emphasize the supposed positive effects of tree-like skyscrapers on the urban environment: recirculating hydroponics and aeroponics that significantly reduce the amount of water needed, collecting rain and treating wastewater, producing photovoltaic green energy, etc. But, curiously, they forget to mention the dark side of it. There are many huge problems inherent to these agritectures:

- Even if a building is largely fenestrated, plants still need soil and additional sunlight to survive. When sunlight is replaced by LEDs, it has a huge energy cost.

- Controlling humidity and air circulation and evacuating the heat released by LEDS also has large energy costs.

- Fertilizers are always necessary, as are pesticides, due to the mildew and other pests found in greenhouses today.

Besides, how could the urban fabric be inclusive of this type of farming? As highlighted by Saskia Sassen, in the broader perspective of the Smart Cities movement: “These technologies have not been sufficiently ‘urbanized’. It is not feasible simply to plop down a new technology in an urban space”.

As beautifully put by Stan Cox and David Van Tassel, tree-like skyscrapers look like a dreamy idea with a solid financial and political hidden agenda, which could ultimately become even more industrialized than modern rural agriculture. Indeed, to defend this type of urban farming, many authors argue that fossil fuels, fertilizers, and government subsidies to industrial farming are also expensive. In doing so, they implicitly assert that vertical farming and industrial farming should be of the same nature and have the same standards, which says a lot about the financial interests and real objectives of urban agriculture. Such a type of urban agriculture is all but sustainable, and can certainly not foster urban sustainability. There is obviously a huge discrepancy between the dream—or the nightmare—and the reality.

These “castles—or skyscrapers—in the sky” are not the most worrying misappropriations of the notion of urban agriculture. They have not been built, anyway (except for Stephano Boeri’s “Vertical Forest” in Milan, in the aftermath of the Expo 2015 “Feed the Planet, Energy For Life !”, but these buildings are not truly high-rise constructions, and besides they are not agricultural holdings but rather residential towers with trees, more like the hanging gardens of Babylon).

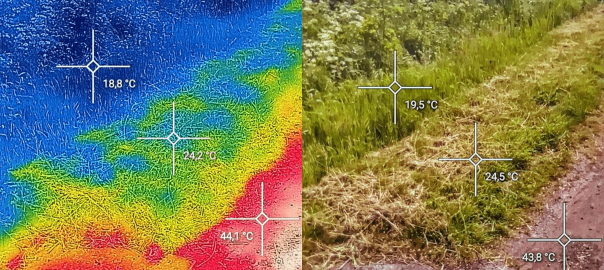

Get back to the ground level: conventional farming within cities is potentially a much graver concern, be it located in a skyscraper or just in the ground. The big issue here is the dissemination of pesticides and fertilizers as well as of the wastes and the by-products of industrial urban agriculture, especially in vine-growing or grain-growing regions—two agricultural productions with high added-value—where vines and fields are frequently incorporated in the city. The inhabitants of such cities are exposed to critical levels of pesticides on a daily basis without them even knowing. Well, they are beginning to know, and it appears that they are not happy at all. In France, many cities are concerned, such as Bordeaux, Reims (the capital of Champagne), and the medium-sized cities of the Parisian basin, such as Orleans or Chartres. It is probably the same elsewhere in Europe and worldwide.

Conventional urban farming: Would you enjoy a nice cup of pesticides?

Take the very well-documented example of Bordeaux. An emblematic case indeed, considering the reputation of Bordeaux wines. Today in France, vine-growing is the second largest consumer of pesticides (20 percent by volume of all the pesticides in France, for only 3.7 percent of farmland in use). You can imagine what the neighbors of these vines passively inhale and swallow. After years of omertà, the inhabitants of the Bordeaux urban area finally started standing up against this agriculture. Farmers and pesticide producers—and local authorities or farmer’s unions, who are sometimes considered as accomplices—are getting sued in court.

All this began in 2014, when twenty-three children and their teacher had been poisoned in their schoolyard in the city of Villeneuve. Last February, the people living near Bordeaux vineyards successfully organized a huge protest against the use of pesticides in urban areas. Several surveys had been disclosed in the preceding weeks that warned them about the impacts of plant protection products on health and on the urban environment. Wine-growing monoculture was especially targeted due to the very frequent spraying of chemicals, including fungicide treatments. According to one of these surveys, hair samples of children going to schools surrounded by vineyards in the Bordeaux region tested positive for 44 pesticides—authorized and unauthorized. Another report mentioned the risks of cancer linked to glyphosate (a systemic herbicide and an organophosphorus compound) used in wine production. The French Ministry of Environment called on the ANSES (Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de l’Alimentation, de l’Environnement et du Travail) to revise this chemical’s existing authorization.

This situation is stupid, considering that many of these chemicals are ineffective, especially those targeting blight, oidium and gray mold, as demonstrated in 2015 by the INRA (French National Research Institute for Agronomy). Why should anyone keep on applying pesticides that yield no results? Well, it gives work to phytosanitary manufacturers and distributors. Besides, wine is an economic sector that carries weight in the Bordeaux area: wine production represents a yearly turnover of 4 billion euros, and is the largest employer in the region. Thus, among the different stakeholders nobody dares to call into question a system of which everyone benefits financially.

The case of Bordeaux is just an example of a much broader issue. In 2015, the NGO Générations Futures carried out tests in houses and apartments located nearby vineyards, cornfields, and industrial orchards, with amazing results. The analysis showed that the inhabitants were living in what the report calls “a pesticide dust-bath.” On average, 20 different chemicals were detected in each dwelling: 14 when near cornfields, 23 when near industrial orchards, and (no surprise) 26 when near vineyards. Even diluron—a herbicide whose use has been officially banned in France since 2008—was discovered in many places. Among those chemicals are 12 endocrine disrupters, which represent 98 percent by weight of all the chemicals detected. Endocrine disrupters are suspected of provoking prostate, testicular, and breast cancers; of triggering hormone system disorders such as diabetes; and of generating fetal development disorders. How about that? Yes, living nearby intensive industrial agriculture in urban areas is not without consequences, and is certainly not sustainable.

When spraying foliage with a plant-protection chemical, only 30 percent to 50 percent of the active product hits its target. Where does the rest go? It is transported in the atmosphere, gets deposited on the ground, and eventually reaches groundwater by leaching. Supposing that you live nearby: you breathe it, you drink it, and—provided that you grow your own vegetables in the contaminated soil and irrigate them with polluted water—you eat it. South of Lyon, people living close to large orchards complain “When we see our neighbor, the farmer, arriving on his tractor wearing his ‘spacesuit’, we lock the kids and ourselves in the house with the doors and windows well closed”. This happens more then 20 times per year between March and September during the growing season, which is when people like to stay outdoors. Not only people living nearby need to be concerned: airborne pollutants are transported quite far from their source. AirParif (an agency accredited by the Ministry of Environment to monitor the air quality in Paris and in the Parisian Region) recently detected (2014) more than 80 different phytosanitary chemicals used in cereal farming in the very center of Paris.

Within the city, farmers and their non-farming neighbors share more than fencelines, and it can be quite challenging to live near industrial agriculture. A hammer can be used indifferently to knock in nails or to shatter skulls, but the hammer is neither bad nor good. It is the person that uses it who decides. The same goes for urban agriculture: All relies on who does what on its behalf.

When trying to determine if urban agriculture may contribute to a sustainable future, the primary question to ask is: Will this agriculture be at the service of the inhabitants? Its success depends on its objectives, its form, and its local ownership by the people concerned.

Once again, my objective here is not to discredit urban agriculture. Conversely, my objective is to illustrate the difference between type of agricultures that help reconfigure more sustainable cities—which I have developed in former posts—and agricultures that endanger sustainability in the city.

François Mancebo

Paris

About the Writer:

Francois Mancebo

François Mancebo, PhD, Director of the IRCS and IATEUR, is professor of urban planning and sustainability at Reims University. He lives in Paris.

So many good points! One of the biggest problems with urban agriculture is the cost. Any good businessman farmer would look for a piece of property to farm that is the most profitable to farm—this will also be easest to farm,m. It will be easy to access every square inch and be as level as possible. It wil be essy to irrigate, and easy to harvest, all comparitive to the other options available, The skyrise, the various small plots of open rooftop, corner lots and indoor hydroponics are definitely not good options. With each difficulty, the costs rise, and no one is going to pay more for produce grown in an expensive rooftop garden, that is the same quality product aa one grown outside of town, just because ir is “urban-sourced.” It is a very bad business model, and won’t last.

I can’t agree. Yes the heat given by a single lead is tiny, but what about the heat given by thousands and thousands of LEDs stucked in confined areas? It is less than with other lighting systems, for sure, but it is still huge and this heat has to be evacuate.

“One day I will live in theory because in theory all goes well”… Yes theoretically, hydroponic systems apply very few crop protection products, but guess what: It usually doesn’t work that well. You always have pests and rodents that finally enter your system, and when this happens what do you do? The control of temperature and moisture is never perfect, and usually mildew also happens quite frequently. And if you want to put things right after this type of event in an indoor closed system, good luck: It is energy consuming, time consuming and it is quite expensive, which also raises questions about the maintenance costs of such systems. Check in real life: There are many examples. You can find them on the Internet, but you can also have a look at Suwon in Korea, or the Dutch PlantLab.

And anyway, the article is not so much about hydroponics but about the dangers of outdoor intensive urban agriculture disguised in sustainable urban farming.

Also:

“Fertilizers are always necessary, as are pesticides, due to the mildew and other pests”

Modern indoor hydroponic systems apply fertilisers in a closed loop – they aren’t discharged. And crop protection products are barely applied at all.

In all, the writer is remarkably ill-informed about the topic he’s chosen to write on.

“evacuating the heat released by LEDS also has large energy costs”

Not so. The heat given out by LEDs is tiny – that’s why they can be arranged so close to crops within high-density multi-storey production units.

One thing not mentioned and perhaps it is another topic is the composting of the organics. Much of it can be done in a Composter. The best in my opinion is the Jora New Era line. http://Www.joracanada.ca.

Growing a garden anywhere will produce not only fresh food but also make growers happy.

Treat a plant with respect and it will reward you.

I taught in an alternate school for decades and I never once have had a plant say to me “go have sex with yourself”

urban agriculture must be organic

The problem is not urban gardening; it is the type gardening. Use organic, no-till gardening in permanent beds. Free info from [email protected]

“…the primary question to ask is: Will this agriculture be at the service of the inhabitants?”

Always a good question to ask about architecture and design!! And if not the inhabitants, then who, and to what end?

muy interesante este artículo