I recently spent a month in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and have been reflecting on my experience ever since. Chiang Mai is a beautiful and vibrant city, rich in culture and history. The Buddhist religion permeates every aspect of the city and surrounding countryside, with temples and symbols of Buddhism everywhere.

What is the essence of the Thai elephant, and what is its meaning in a modern global society? This is an especially germane subject for the largely urban tourists who flock to Chiang Mai from around the world—most of whom, it might be fair to say, have had few, if any, experiences with real elephants. Arguably, opinions and feelings about this mysterious “other” may largely be based on pop culture imagery, where portrayals of elephants run the gamut from wise beast to circus clown.

In Chiang Mai, the center of Thai elephant tourism, the chance exists to see real, live elephants in the nearby countryside (they are no longer allowed in the city). The range of tourist offerings is wide—from highly structured captive elephant shows to revelatory one-on-one experiences with rescued elephants in natural forest settings.

How or whether a tourist to Chiang Mai selects a live elephant experience—and what type of experience they choose—could depend in part on the images of elephants encountered in Chiang Mai city. The city has had a close association with elephants since its inception more than 720 years ago, so it is not hard to find eye-catching depictions of elephants around almost every corner. What is striking about these portrayals, though, is that the elephants are almost never shown as wild animals, unencumbered by the trappings of human culture. Instead, they are portrayed as ornate, decorated, subservient beasts obligated to serve human needs.

Does this constant portrayal of elephants as domesticated beasts of burden subtly influence how modern tourists, and indeed Thai citizens, think of elephants today, and what they might consider as “normal” treatment of elephants, particularly as vehicles for human entertainment? In this capacity, captive elephants are made to paint pictures, make music, kick balls, stand on their heads, roll over, reenact ancient battles, and carry tourists on their backs. Of course, no wild elephant would perform like this, so captive elephants must be taught, normally through harsh methods, to obey commands. This is the dark side of elephant entertainment, and it is fueling a growing demand to experience elephants on their own terms, free from human domination.

The typical portrayal of elephants as beasts of burden in popular culture, and as frequently experienced in the art of Chiang Mai city, likely does have meaning and resonance. With populations of wild elephants rapidly declining in Thailand, and an unending demand for captive elephants to fuel the growing tourism industry, the knowledgeable Chiang Mai traveler can certainly appreciate the historic representation of elephants in Thai culture while choosing not to buy into its current exploitative forms.

A very brief history of Thai elephants

The Thai people have a long history with the elephant, which can be traced back at least to the Sukhothai period about 700 years ago. The first recorded use of elephants in Thailand, formerly known as Siam, was during the war between King Jhunsri Inthradhit of Sukhothai and King Samchon of Chod, when elephants were used in battle. The Thai people were allowed to capture wild elephants during that time, but the number of domesticated or wild elephants was not recorded. It was known that people had the knowledge and experience to keep and use elephants in the Sukhothai period.

During King Narai’s reign between 1633 and 1688, King Louis XIV’s envoy to Siam wrote that there were approximately 20,000 domesticated elephants in the Kingdom, and that these animals were used in warfare and were honored with noble titles after a victory of the King’s forces. It was noted that the outcome of ancient wars was in part determined by the number of elephants in its service, with the winning side usually having the most and the largest elephants. Elephants were also used for transportation of people and goods along well-worn routes. It was estimated that during King Narai’s reign, there were approximately 200,000 elephants living in the jungles of Siam (Pimmanrojnagool et al, 2002).

Pimmanrojnagool et al. also note that in the ancient past, people used elephants for everyday life, and the lives of people and elephants were inseparable. However, with colonization by Western powers and the introduction of long-range weapons, the use of elephants in war decreased until they were no longer used in the front lines of battle. The role of captive elephants shifted from war to logging, where they were noted for their ability to pull half of their weight, or about 1,000–2,000 kg. According to Pimmanrojnagool, in Chiang Mai alone, 20,000 elephants were recorded working in the logging industry during the reign of King Rama V the Great (1868-1910), while the demand for additional wild elephants was endless.

Some of the elephants that were captured were “white elephants,” notable for the pale color of their skin. These white elephants legally belonged to the King and were housed in the palace. During the reign of King Rama V, there were 19 white elephants in his palace. Thai Buddhists believe that white elephants generally symbolize the power of the King. Because white elephants symbolized the King’s power, people were encouraged to capture elephants in the hope that white ones would be discovered. A person who hurt or wounded a white elephant would receive the death penalty, as would his family (Pimmanrojnagool et al, 2002). The current King of Thailand, HM King Bhumibol, keeps ten white elephants at the Royal Elephant Stables near Chiang Mai.

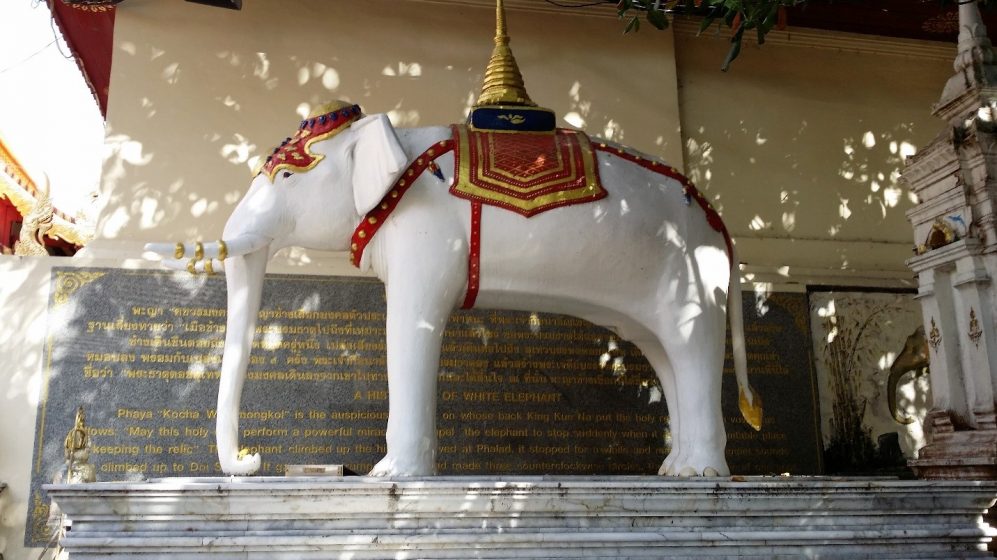

Elephants in general have been historically revered by the Thai people, and ancient cultural and artistic representations of them abound in and around Chiang Mai. For instance, the famous Wat Phra Doi Suthep Temple on the outskirts of Chiang Mai was founded in the 14th century at the spot where a legendary white elephant, said to be carrying a holy relic of the Lord Buddha, climbed Doi Oy Chang, or Sugar Elephant Mountain as it was then known, when he stopped near the peak, trumpeted three times, then laid down and passed away. The king ordered the temple to be built at that exact spot, and today a shrine to the sacred white elephant greets visitors to Doi Suthep temple, and every Thai student knows its founding legend. Inside the temple is a series of beautiful mural paintings depicting the life of Buddha, many of which feature domesticated elephants in various scenes along the Buddha’s journey to enlightenment.

At the turn of the 20th century, it was estimated that there were over 100,000 Asian elephants in Thailand, but by the turn of the 21st century, those numbers had precipitously plummeted to less than 5,000. And, of those, only about 1,000 are thought to be left in the wild, almost exclusively in the Khao Yai National Park and the Thungyai-Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuaries in central Thailand. The remaining are domesticated elephants, used predominantly in the tourism industry.

The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as endangered on its Red List of Threatened Animals. Since the 1970s, no license has been issued for capturing wild elephants in Thailand, although habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation, and poaching continue to cause elephant numbers to decline in every part of the country. Only 1 percent of the elephant population that existed in King Narai’s reign remains today.

In 1989, the Thai Government suspended all logging operations in the country due to severe flooding caused by extensive deforestation. This effectively put domesticated elephants and their mahouts out of work. Unlike wild elephants, which are managed by the Ministry of Forestry, captive or domesticated elephants are considered by law to be the equivalent of draught animals and are treated as private property. As such, they have little protection against being worked by their owners.

With the loss of their traditional role in war and logging, elephants seem to have also lost the noble and revered status they once enjoyed. The cost of maintaining an elephant is high, and Thai society generally considers that a domesticated elephant must earn its keep. With over 2,000 captive elephants in need of food and maintenance, it is not surprising that the Thai government has increasingly turned to the growing tourism industry as a way to manage and maintain the large captive elephant population. Thus, by the vagaries of time and circumstance, the fortunes of captive elephants are now firmly tied to tourism.

Leading up to modern times, images of the elephant have largely continued to reflect back their traditional role as either highly decorated (somewhat mythical) beasts or as domesticated working animals. These images may well suit the artistic sensibilities of their creators, but an inevitable consequence may be a subliminal understanding of the elephant as a service animal. Certainly, artistic representations of decorated, domesticated elephants seem popular with tourists, who face an unending variety of elephant-themed jewelry, clothing, handbags, prints, carvings, cards, statues, and various other portrayals to pick from.

Although many tourists may not question the insertion of captive elephants and their artistic representations into the tourism schema, the relationship has not generally been a happy one for the elephants, with many abuses occurring as elephants are forced to work long hours performing unnatural activities, often under considerably less than optimal conditions. But, with government support for tourism firmly entrenched, and the need to find a new role for elephants to support themselves, one might think elephants’ fates are sealed.

However, new ways of thinking about elephants are beginning to emerge as urban populations the world over start to question the moral and ethical dimensions of this unique human-animal relationship. This change in thinking is increasingly being reflected in the way elephants are portrayed in popular art and culture.

The changing face of elephant tourism in Chiang Mai

Thailand is a prime international tourist destination; it attracted almost 30 million visitors in 2015, many of whom come to northern Thailand to experience authentic Thai and Buddhist culture, the heart of which is in Chiang Mai city and province. As noted, Chiang Mai is also the heart of elephant tourism, offering a range of experiences for tourists.

International tourism has been Thailand’s single biggest foreign exchange earner since the early 2000s, and the need to develop tourism products to suit foreign visitors has included many animal-related offerings. In the Chiang Mai vicinity, there are numerous tiger, monkey, and elephant venues, each offering pre-packaged shows and activities to expectant tourists. Most often these shows involve trained animals performing tricks and stunts in highly controlled settings.

To promote the transition of elephants from logging into tourism, the Thai Government established the Thai Elephant Conservation Centre (TECC) which began as a “Young Elephant Training Centre” for elephants and mahouts, but soon began offering tourist rides and short shows for elephants to display the skills they had learned at the Centre, including skidding and pulling logs, playing musical instruments, and painting pictures. This type of offering has caught on with the private sector and a number of elephant camps have opened up in the Chiang Mai area aimed at the international tourism market.

Because of the fickle nature of international tourism, the TECC has started to explore other avenues to demonstrate the importance of conserving wild and domesticated elephants in Thailand, arguing that tourist rides and tricks “might not be the basis for funding elephant conservation in the longer term” (Duffy, et al, 2010).

Indeed, the TECC has begun to see that the long-term survival of elephants in Thailand might depend more on demonstrating their wider importance to the people of Thailand and to the world, rather than just considering their market value.

Still, as Rosaleen Duffy and Lorraine Moore state (2010, p. 753), very few people in Thailand believe that “culture alone can save the elephant”. Instead, they believe that, due to the high number of captive elephants and the amount of money required to keep a captive elephant, the survival of domesticated elephants will depend on their ability to pay their way, either in the tourism industry or by providing services to people.

As Kontogeorgopoulos argues (2009, p. 443), “Thailand has failed to conserve elephants based on their intrinsic worth as living creatures, and so their future depends on demonstrating their economic importance and utility to human beings.”

That being said, people are trying new and innovative ways to help elephants sustain themselves through tourism. These approaches don’t rely on forced performances and restrictive living conditions. For instance, the approach taken by Sangduen “Lek” Chailert at the world-famous Elephant Nature Park, a 2,000-acre sanctuary outside of Chiang Mai, introduces a concept of promoting elephant conservation through responsible ecotourism which utilizes a nature-based learning experience to help save and sustain more than 40 formerly abused elephants that worked in the logging, entertainment, and tourism industries. This approach provides “learning journeys” for visitors, while also improving the well-being of local villagers (Lin, T., 2012).

This successful model is attracting growing numbers of tourists worldwide, with annual visitor increases of 10-15 percent (Lin, T., 2012). Visits can be booked online or from Chiang Mai. The basic experience at the park is to spend a day or longer with elephants in a natural setting, interacting with the animals on their own terms, without them being forced to perform or to provide rides.

The experience of standing or walking next to a free elephant is overwhelming in its simple power. It teaches respect, empathy, and compassion for these gentle giants who have endured so much in their lifetimes. This non-traditional use of elephants was resisted at first by local Thai people, who were accustomed to more mainstream tourist offerings. However, the idea is slowly catching on as it proves to be an economically viable model (Lin, T., 2012). It offers an alternative path forward for humans and elephants, whose lives and fates are inextricably woven together in this region.

Art and life

Does art imitate life or life imitate art? In the case of elephant portrayals in the city of Chiang Mai, Thailand, both are true. The depictions of elephants to be found in every corner of the city certainly reflect the historic role of elephants as beasts of burden.

As we have seen, in the ancient past, wild elephants were captured for the King and achieved noble status for their bravery in war. They were revered by Buddhists as symbols of the King’s power, and elephants were portrayed carrying Buddha himself in exquisite murals found at the revered Wat Phra Doi Suthep temple outside of Chiang Mai. Elephants were important in building the Thai economy through their role in logging and transportation, and, more recently, in international tourism. The art of elephants in Chiang Mai certainly reflects this utilitarian view of elephants, while also managing to imbue them with majestic power and inward grace.

More recently, different conceptualizations of elephants have started to come to the fore, with more considered and nuanced ideas of elephants and their relationship to humans. The newest art in Chiang Mai portrays elephants in more natural—albeit colorful—unadorned poses, with no trace of material culture attached to their bodies. Is life starting to imitate this type of art? And, how might these new artistic renderings of elephants in the city influence the way people choose to experience the real thing?

From Chiang Mai’s vibrant street markets, where large, colorful paintings of unencumbered elephants dominate, to the epiphanies to be found by interacting with freed elephants at the Elephant Nature Park, the tide may be turning for the captive elephants of Chiang Mai. Let’s hope so—there is not a moment to waste in transforming our relationship to these magnificent creatures into one of dignity.

Through its evolving artistic and cultural depictions, images of elephants continue to imbue Chiang Mai with a magical realism that is hard to resist. Let’s now transfer this into meaningful action on behalf of the real elephants of Chiang Mai.

Lynn Wilson

Vancouver

References

Duffy, R., and Lorraine Moore (2010). Elephant-back tourism in Thailand and Botswana. Antipod, 42 (3), pp. 738-762.

Kontogeorgopoulos, N. (2009). The role of tourism in elephant welfare in Northern Thailand. Journal of Tourism, X (2), pp. 1-19.

Kontogeorgopoulos, N. (2009). Wildlife tourism in semi-captive settings. Current Issues in Tourism, 12 (5/6), pp. 429-449.

Lin, T. (2012). Cross-platform framing and cross-cultural adaptation. Examining elephant conservation in Thailand. Environmental Communication, 6 (2), pp. 193-211.

Pimmanrojnagool, V. (2002). A study of street wandering elephants in Bangkok and the socio-economic life of their mahouts. In Giants on our hands. Proceedings of the international workshop on the domesticated Asian elephant. Bangkok, Thailand, February 2001, pp. 35-42.

About the Writer:

Lynn Wilson

Lynn Wilson (MCIP, RPP) is a regional park planner for a 33,000-acre natural area system on Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation