41% of the total land area in the densely built city of Mumbai must be reserved as open spaces. A change in the mindset, along with not so radical changes in the development plan, can make this city very eco sensitive and a sustainable urbanized centre to live in.

We feel the need to prepare development plans with open spaces expansion being the basis of planning for Indian cities and towns because of worsening conditions of our urban life. Deteriorating quality of life, growth of informal sector, degradation and deprivation of open spaces, destruction of the environment and the abuse of the ecological assets including water bodies have rendered our cities into a regrettable state. Also the high cost of urban transportation, lack of housing for a majority of the people, inadequate and costly amenities, fragile services, overwhelming real estate thrust, colonization of land and arbitrary decisions in urban development make our cities an arduous place to live in. Our attempts at city development are tragically fragmented, disparate, contradictory and almost always reactionary. Anarchic growth marks the character of most Indian towns and cities.

In response to crises and adversities, the government and development agencies have only looked at ways to exploit the real estate potential of the city. Real estate turnover, in fact has been the single largest thrust of our cities’ development even at the cost of social amenities, basic infrastructure appraisal and loss of open spaces. Our cities are controlled by a real estate agenda and arbitrary changes in land use and development control regulations which work against public good.

As towns expand, their open spaces are shrinking. The democratic ‘space’ that ensures accountability and enables dissent is also shrinking. Over the years, open spaces become ‘leftovers’ or residual spaces after construction potential has been exploited. Hence we need plans that redefine the ‘notion’ of open spaces to go beyond gardens and recreational grounds –– to include the vast, diverse natural assets of our cities, including rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds, exhausted quarries, mangroves, wetlands, beaches and the seafronts. Plans that aim to create non-barricaded, non-exclusive, non-elitist spaces that provide access to all citizens. Plans that ensure open spaces are not only available but are geographically and culturally integral to neighbourhoods and a participatory community life. Plans that redefine land use and development, placing people and community life at the centre of planning — not merely real estate and construction potential.

The objectives for any city should be to expand its open spaces by identifying its natural assets, preserving them and designing them to turn into public spaces for recreation. The aim should be to expand and network public open spaces, conserve natural assets & protect eco-sensitive borders, prepare a comprehensive waterfronts/natural assets plan, establish walking and cycling tracks to induce health enhancing behavior while promoting energy efficient transport and promote social, cultural and recreational opportunities.

Also, interaction in public spaces is an old tradition and needs to be policy of contemporary cities. A good city should have a good community life. Urbanized centers world over have a tendency to create individual spaces and gated communities which result in aloofness, loneliness and depressed lifestyles. Sense of community fades and individualism takes over. According to urbanologist Jan Gehl when the city whole heartedly invites to walk, stand and sit in the city’s common space a new urban pattern emerges: more people walk and stay in the city. We need to design cities as meeting places — for small events and larger perspectives. City designers need to set the stage for necessary activities like walking, optional activities like enjoying a view and social activities like tempting public interaction. Public institutions tempt public interaction and greatly enhance and consolidate social, cultural and community aspirations. Historically public institutions like libraries, cultural centers, theatres, planned squares and chowks, etc have led to significant movements, demonstrations and alternate thinking. For now and for the future it is necessary to establish public institutions to contribute and enrich the life of all the people in the city and facilitate growth of public engagement and knowledge for human development. By building public spaces we weave psychological and intellectual growth into a comprehensive physical plan while bringing substance to the notion of public realm.

Open Mumbai

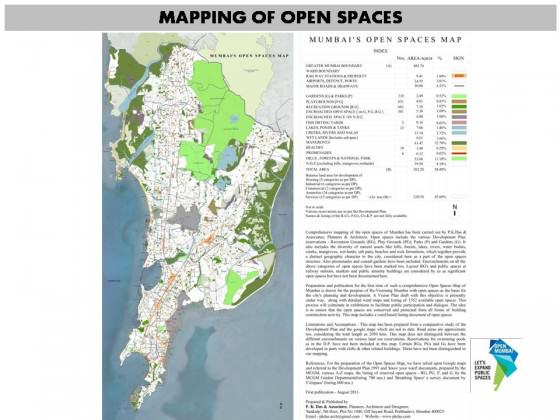

The ‘Open Mumbai’ plan takes into consideration the various reservations in the existing development plan of the city. The recreation grounds, playgrounds, gardens, parks, rivers, nullahs, hills are already marked in the development plan; we are recognizing them and linking them with marginal open spaces and pavements along roads. No radical land use changes are proposed, except to limit further conversion of natural assets to buildable land. Such measures would make implementation simpler and successful.The various reservations are most often segregated and individual and so we are bringing them together to create a larger network of public spaces.

For example, we are maintaining the land along the mangroves as eco sensitive border but integrating it in the urbanized area with the concept of promenades and cycling tracks and thus merging it with the idea of open spaces, to experience them as a part of the public realm. This will also contribute to enormous recreational activity as citizens can walk, cycle along the marshy bushes and also learn about the ecosystem. Children too will get a chance to play in natural, open to sky surroundings instead of just visiting artificial atriums created in malls — the notion of contemporary public spaces today. Thus the idea of creating green spaces is not just designated to the building of cute and fancy parks and gardens but creating a network of open spaces, open and clear forever for all the citizens equally.

‘Open Mumbai’ Plan objectives and elements (Open Mumbai Map)

Maps are an insight into a nation’s progress. Not maps that define national boundaries, but maps that define cities and neighbourhoods. Maps that reveal the resources we have and how we share them. And the resources we may have lost. Open spaces, water bodies, vegetation, wildlife. Maps that make us vigilant and protective. Ours is a voluntary effort that has helped create a basis for the ‘Open Mumbai’ vision plan. An even more concerted effort by government is needed to continually map the city in extensive detail…if we are to build a more equitable city for its citizens.

Objectives:

- Expand and network public open spaces

- Conserve natural assets & protect eco-sensitive borders

- Prepare a comprehensive waterfronts plan

- Establish walking and cycling tracks

- Promote social, cultural and recreational opportunities

- Evolve and facilitate participatory governance practices

- Democratise public spaces

- Undertake necessary amendments in the DP and DCR

‘Open Mumbai’ Plan Elements:

- Vast Seafronts

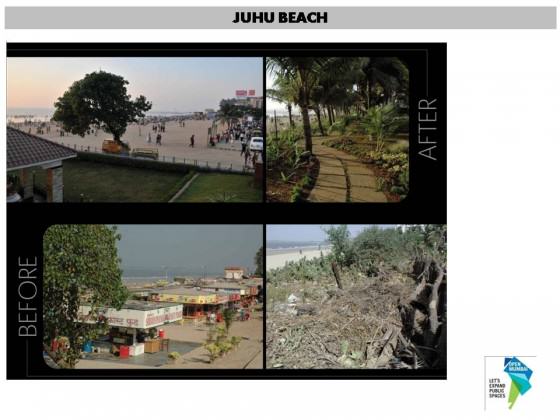

- Beaches

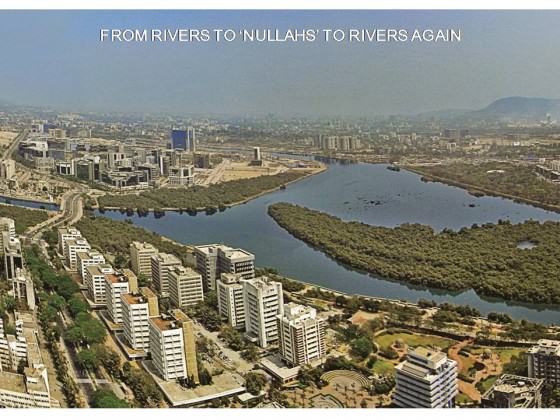

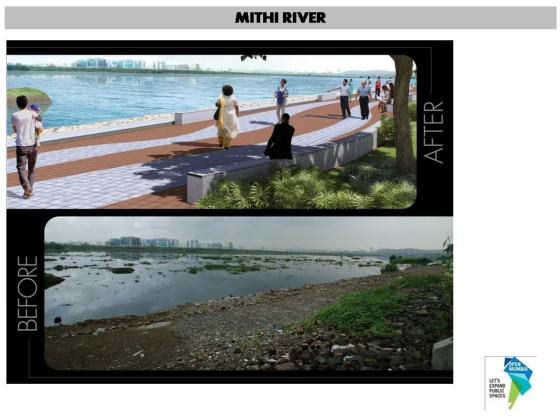

- From Rivers To Nullah’s To Rivers Again

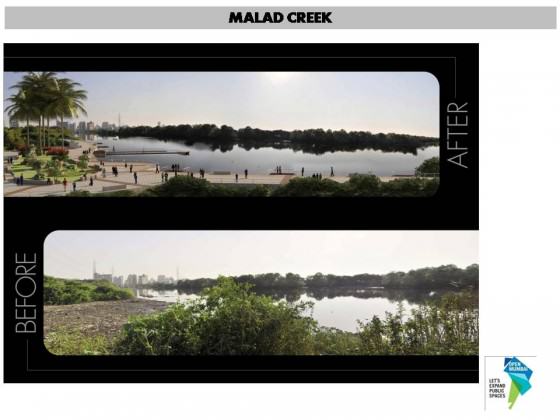

- Creeks and Mangroves

- Wetlands Conservation

- Lakes Ponds and Tanks

- Integration Of Nullah’s

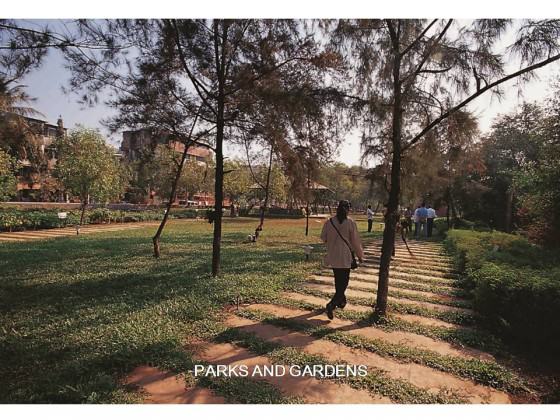

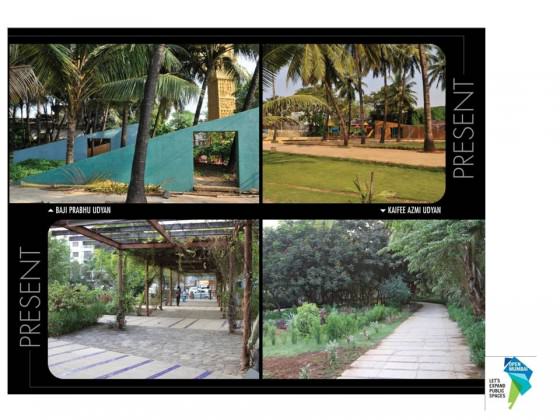

- Parks and Gardens

- Plots and layout RG’s

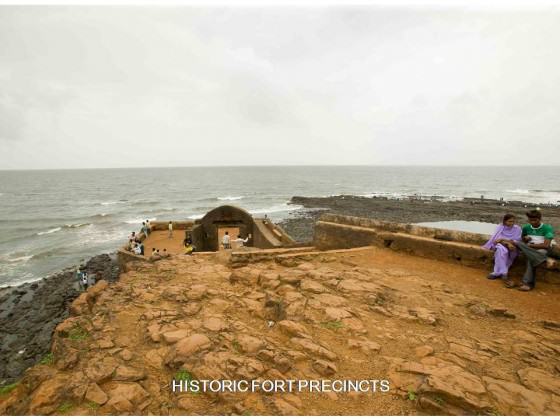

- Historic forts and Precincts

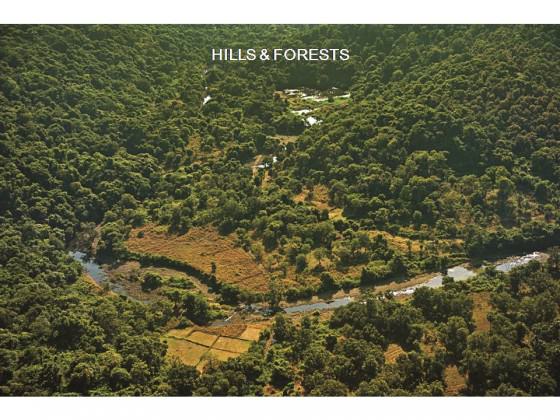

- Hills and forests

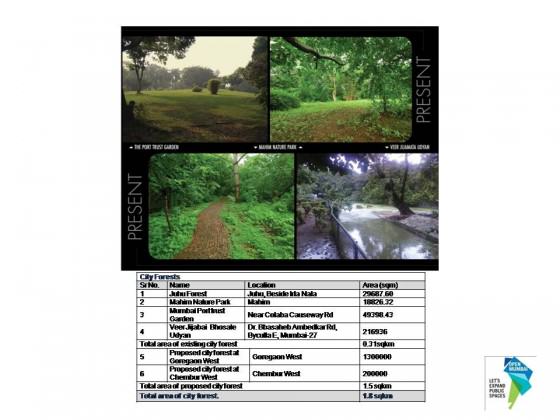

- City Forests

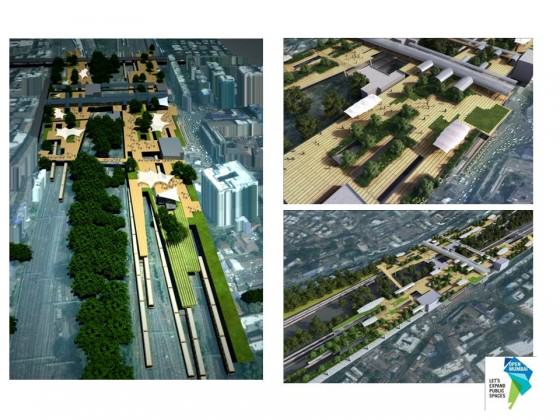

- ‘Open’ people-friendly Railway Stations

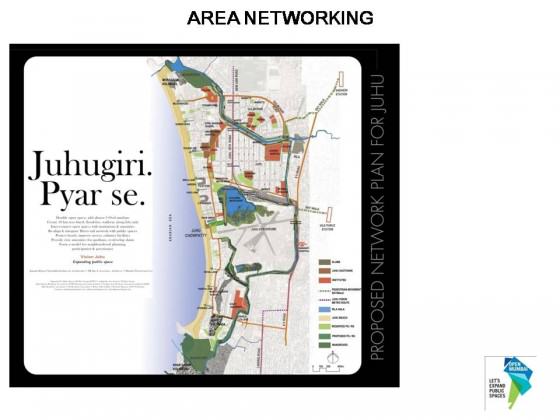

- Area Networking

The Way Forward: Summary

The Way Forward: Summary

- Reserve open space around or adjoining the various natural assets and define boundaries of various elements like seafronts, beaches, rivers, creeks and mangroves, wetlands, lakes, ponds, tanks, nullahs, parks and gardens, plots and layout recreational grounds, historic forts and precincts, hills and forests, city forests which will help in creating buffer zones in order to arrest the continuing abuse of these assets.

- Earmark spaces that would enable the networking of the various categories of open spaces. These networks may take the form of avenues, ‘squares’, plaza’s, walking and cycling tracks, landscapes, reserved as ‘Open Networks’.

- Reserve spaces adjoining markets and public buildings as ‘Open Spaces’.

- Reserve spaces adjoining railway stations and other public transportation hubs as ‘Open Spaces’ and reserve the precincts as special planning areas.

- Reserve all waterfronts as open spaces.

- Demarcate the various beaches as reserved ‘Open and Conservation Precincts’.

- Demarcate and reserve 6m open space on both sides of the nullahs and develop them as public open space while also providing access for the maintenance of the nullah.

- Identification and demarcation of NDZ land to be reserved as compulsory open spaces, marked as ‘Open NDZ’

- Distinguish hills and forests from all other open spaces reservation.

- Limit building/civil construction to public conveniences like toilets, drinking water fountains & assistance booths in all accessible spaces.

- Permit landscape development to only include promenades, plantations, paving, walkways, seating, lighting, signage, drainage, boardwalks, cantilever decks, railings, steps, plaza’s, open-air performing spaces and edge retaining walls along the natural assets.

- Make necessary modifications to ensure that Recreational Grounds (RGs) are effective open spaces for recreation and not fragmented, misused and built upon at anytime. Also, layout RGs be notified as Designated Protected reservations.

- It is the State government and the Municipal Corporation who have to initiate the planning and development of public open spaces. Therefore, public participation and dialogue on issues relating to public open spaces becomes necessary.

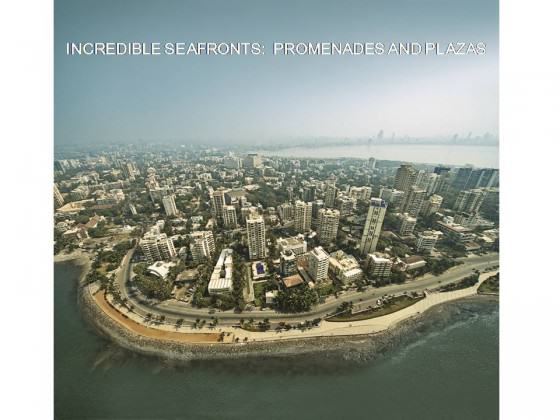

Vast seafronts: 0.95 sq km

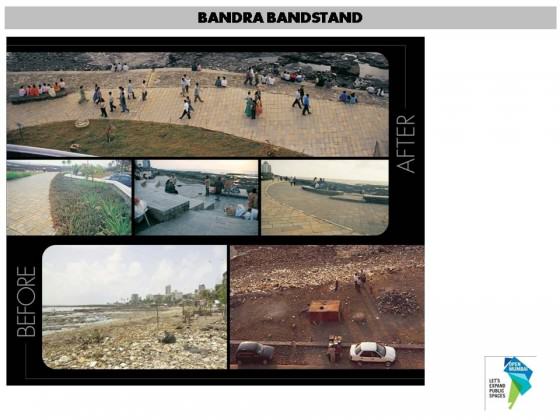

With 149 kms of coastline and seven interconnected islands, Mumbai is a city on the sea. A city with few parallels in the world. Yet how much of this coastline is respected, preserved and used as planned public space? The promenades at Carter Road and Bandstand in Bandra demonstrate how neighbourhood initiatives, ‘inclusive’ non-elitist planning and government and private support can transform our seafronts meaningfully.

Mumbai has a whole series of once iconic waterfronts that have the potential of becoming vibrant, open public spaces, providing access to all sections of society.

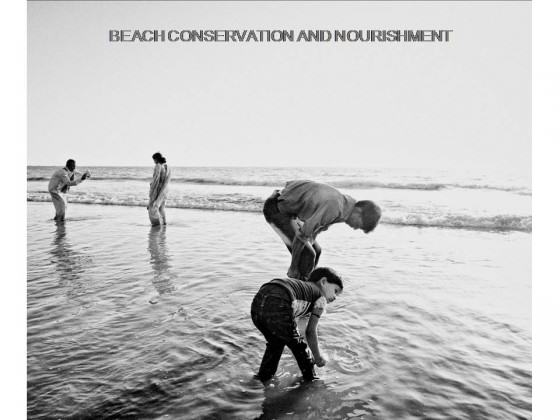

Beach conservation and nourishment: 16 km in length

Beach conservation and nourishment: 16 km in length

With 16 kilometers of beaches, Mumbai should have an abundance of public open spaces and opportunities to enjoy the Arabian Sea. Unfortunately, our beaches are shrinking due to unbridled construction along the coast and consequent ecological damage. Some of the damage can be reversed by a beach conservation and nourishment programme similar to the one undertaken in Tel Aviv, Israel. On a modest scale, this is being attempted at Dadar Prabhadevi with encouraging results that can be replicated at other beaches in the city. As the beach ‘regenerates’, an inevitable corollary is neighbourhood pride that ensures ongoing conservation.

From rivers to ‘Nullahs’ to rivers again: 81.4 kms in length — both banks

From rivers to ‘Nullahs’ to rivers again: 81.4 kms in length — both banks

Did you know that Mumbai has four rivers? Mithi, Oshiwara, Dahisar and Poisar, together 40.7 kms long? Almost invisible to the city’s population, these rivers are waiting to be ‘discovered’, protected and their shores revitalised as open public spaces. Mumbai’s riverfronts can yield 81.4 km of walking and cycling pathways. They are the ‘veins’ that can be networked with other public spaces, creating a veritable ‘tree of life’ for the city.

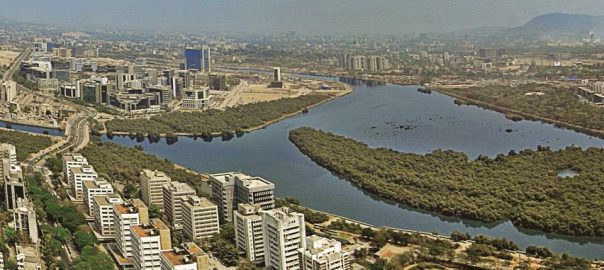

Creeks and mangroves: 34 km

Creeks and mangroves: 34 km

Mumbai is one of the few cities in the world where over 70 sq km of creeks and mangroves coexist with the city’s land mass. A proven natural barrier against high tides, cyclonic winds and coastal erosion, their environs also represent unused potential for the development of ecologically-sensitive public open spaces. The city stands to gain approximately 33 km of boardwalks and promenades in the process. By creating these spaces alongside ecologically rich creeks and mangroves, we open them to public vigilance and therefore greater protection too.

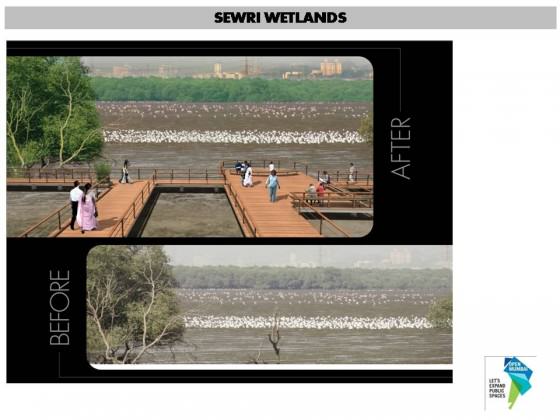

Wetland conservation: 10 km

Wetland conservation: 10 km

Every year, hundreds of flamingoes temporarily migrate to Mumbai, drawn to our urban wetlands. A part of nature’s bio-engineering, wetlands protect our coastlines, check soil erosion, keep floods at bay and breed precious marine life. We can integrate our wetlands by creating boardwalks, promenades and gardens along their edges. Let us protect and enjoy our rich natural treasures, instead of building upon them.

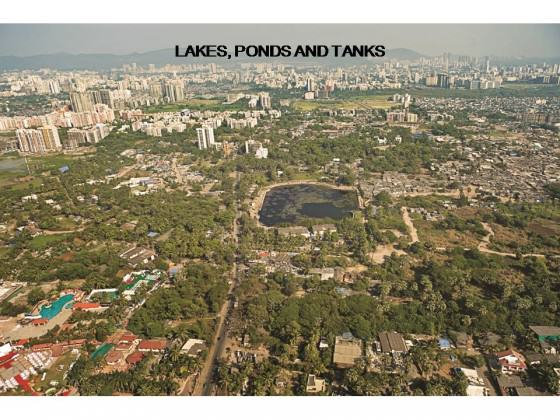

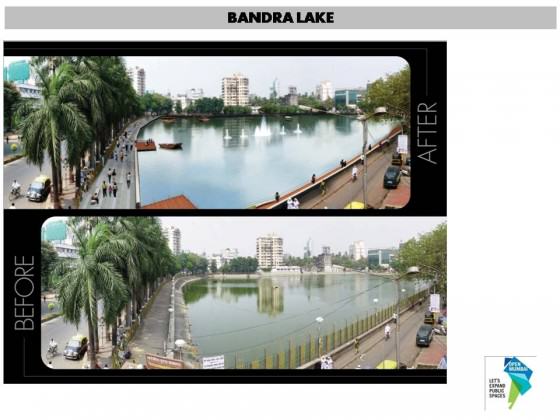

Lakes, ponds and tanks: 2.4 km

Lakes, ponds and tanks: 2.4 km

Compared with our attitude to other natural resources, Mumbai has recognised the importance of its lakes, be it Vihar, Tulsi or even Powai. Our ponds and tanks, however, are an altogether different matter. Instead of losing our once-pristine ponds and tanks to pollution, waste disposal and development, we need to work towards their conservation, so that we can enjoy them. Instead of barricading them, let us network our lakes, along with our ponds and tanks, with other neighborhood open spaces so they become an organic part of the city.

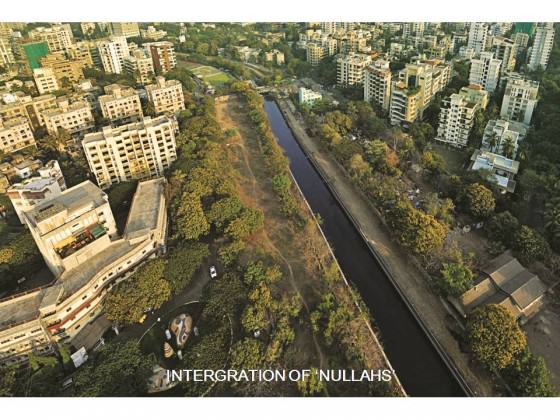

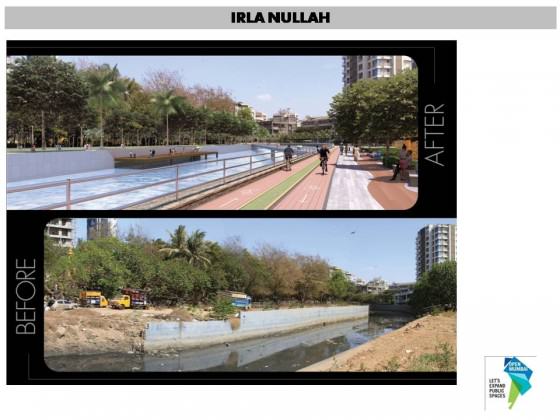

Integration of ‘Nullahs’: 96 kms

Integration of ‘Nullahs’: 96 kms

Mumbai has 16 planned nullahs covering a length of 48 kms. Designed to be storm water drains meant to protect the city from flooding, these nullahs are misused as dumping grounds for sewage. Let us protect these vital lifelines from abuse and keep them clean. Let us integrate these spaces into our neighborhoods, create walking and cycling tracks and plantations along their sides.

Playgrounds, parks and gardens: 13.37 sq km

Playgrounds, parks and gardens: 13.37 sq km

London has 31.68 square meters of open space per person. New York has 26.4 square meters. In comparison, Mumbai has just 1.58 square meters of open space per person. Under current development policies, this will further reduce to 0.87 square meters per person. Mumbai’s Development Plan (DP) provides 2053 playgrounds and gardens covering 18.98 square km. Of this, 5.3 square km have already been encroached upon.

The city urgently needs to safeguard and expand its green space through gardens and parks that provide opportunities for enriching community life and expand open spaces. We need to turn all the marginal open spaces along nullahs, roads, transportation links, public buildings and our vast natural assets into welcoming gardens and parks.

Plots and layout Recreational Grounds: 23.15 sq km

Plots and layout Recreational Grounds: 23.15 sq km

In an effort to maintain our green cover, development regulations stipulate that a certain portion of all plot and layout development have to be reserved for Recreational Grounds (RGs). Despite these guidelines, there are no official records or audits that ensure compliance by builders with these regulations. This invariably leaves these spaces open for misuse through further construction, which further depletes our open spaces.

Let us ensure that the roughly 23.15 sq km of open spaces earmarked for Recreational Grounds, which constitute 10.49% of Mumbai’s ‘developable’ land area, is opened up for public use, instead of being misused.

Historic forts and precincts: 0.083 sq km

Mumbai has a rich martial heritage that includes six forts, designated as ‘protected’ areas but in practice entirely neglected. The transformation of the once derelict Bandra Fort into a cultural hub that dominates the urban landscape, proves that all it takes to restore our imposing forts is determined, concerted effort. Mumbai’s ancient forts represent important landmarks in the city’s history. Developing them into meaningful public open spaces as neighbourhood initiatives, supported by government, can ensure greater vigilance and protection of these sites.

In a city where land costs are among the highest on earth, there actually exists something even more precious — small urban ‘forests’. The verdant BPT Gardens in Colaba, the green cover around Juhu’s Irla nullah (created by an enlightened former-municipal commissioner), and the hidden gem that was born on a dumping ground, the Mahim Nature Park, are only a fraction of the potential that exists.

Instead of cutting down trees and small urban ‘forests’ in the name of development, let us create new ‘forests’ as part of developmental projects, by adding buffer zones along and around creeks,water bodies and coastline edges. Let us create landscapes that are contiguous, enabling networking of open spaces and inter-weaving of neighbourhoods.

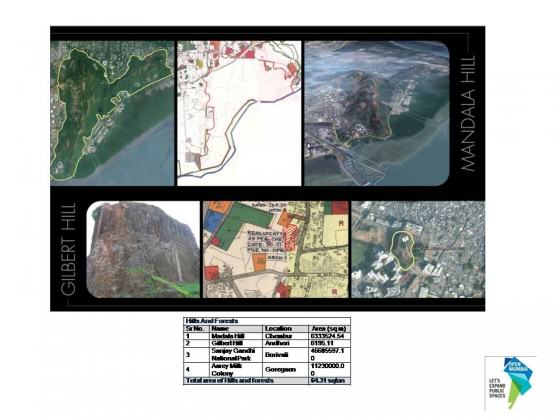

Development control regulations for hills: 64.31 sq km

Development control regulations for hills: 64.31 sq km

- Restoration of the hills damaged by quarrying and re-forestation.

- Protect the National park by defining its borders with walking and cycling tracks, along with necessary resting places.

- These hills and forests should further be declared as ‘Conservation Areas’ to ensure their safekeeping.

Name, Location, Total Area (square meters)

- Mandala Hill, Chembur 6,333,524.54

- Gilbert Hill, Andheri 6,195.11

- Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Borivali 46,685,597.10

- Aarey Milk Colony, Goregaon 11,230,000.00

- Total: 64.31 square km

Open peopl-friendly railway stations: 0.06 sq km

Trains are the lifeline of Mumbai. Almost 7 million Mumbaikars use them every day to travel to work. Our city has 51 stations, covering 155 acres. Yet, crowds, congestion and chaos are the words that come to mind when we think about the hubs that link our trains — the railway stations.

A simple act of building ‘Roof Plazas’ at railway stations, with multiple connectivity to neighbourhoods and their surrounding streets, could ease some of this congestion, and greatly improve the quality of travel. With extensive landscaping and public facilities, these Roof Plazas would not only provide substantial open space, but also enable easy access to and from platforms, help commuter dispersal and contribute substantially

Roads and pedestrian avenues

Roads and pedestrian avenues

In our Open Mumbai Plan, we propose comprehensive planning of roads having dedicated and segregated steady lanes to allow the flow of traffic and efficient mobility by various modes of transport including walking and cycling. These roads would then form an integral part of the open space networks throughout the city.

In this plan, many of the arterial roads are redesigned as one-way roads with additional lanes along with adequate space for walking and dedicated cycling tracks. Wider one-way roads will facilitate faster movement of traffic thereby de-congesting the roads. Arterial roads that are parallel with each other would be interconnected laterally to form rings for easy access and dispersal. This road pattern is illustrated in the case of DN Road in the fort area. In our plan certain other roads are re-oriented largely for pedestrian movement and cycling along with motorable service lanes in cases where the buildings have no other access road. The road from Churchgate to Flora Fountain and Horniman Circle is an example of such conversion. Many neighborhood roads throughout the city can be similarly altered.

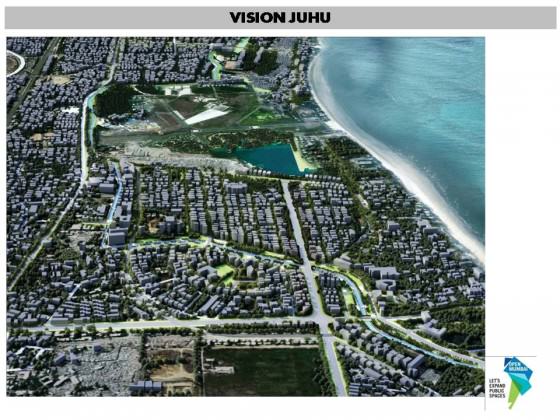

Mumbai, like any other global city, is an amalgamation of a diverse set of neighborhoods, each with distinct identities, opportunities, strengths and weaknesses. Neighborhood planning which focuses on individual neighborhoods, without losing sight of the city at a macro level, empowers local residents and leads to quicker development, as seen in the case of ‘Vision Juhu’.

The aim? To develop contiguous open spaces by interconnecting various areas open to the public. A ‘Green Spine’ that nourishes community life, neighbourhood engagement and public participation.

Conclusion

Conclusion

These plans and proposals are essentially rooted in ideas of conservation, restoration, recycling, re-planning and re-structuring existing realities and their spatial transformation. Rather than mega projects with large-scale displacements and enormous revenue burdens, this approach is based on more pragmatic and people-oriented alternatives.

Firstly, we believe that all re-developments should recognise and respect existing realities as part of the planning and urban development process. Public open spaces as the basis of planning are an effective means to achieve these objectives. Such an approach engages citizens, leads to better quality life and ensures a more ‘democratic’, more equitable city.

By achieving intensive levels of citizens’ participation we wish to engage and influence governments to devise comprehensive plans for public spaces and re-envisioning the city with open spaces being the basis for planning including the vast natural assets of the city.

P.K. Das

Mumbai

All images are © Open Mumbai and P.K. Das

About the Writer:

PK Das

P.K. Das is popularly known as an Architect-Activist. With an extremely strong emphasis on participatory planning, he hopes to integrate architecture and democracy to bring about desired social changes in the country.

The constructively written article is very nice. The insights of the city shown here through words and the great plan for maintaining a percent of open space are highly appreciated. Thanks a lot Mr. PK Das for spreading awareness through your article.

To: Peeyush Sekhsaria,

The central issue before us is the integration of the vast extent of natural assets in the city of Mumbai with built environment and daily life of people.

All edges of the natural assets are abused and misused today, being used as dumping grounds for debris, solid-waste, etc. This has greatly damaged mangroves, wet-lands, rivers, creeks, etc. Our objective is therefore to achieve a buffer zone along side all natural assets in the city as interface area. These buffer zones are being proposed in my plan as public open spaces facilitating walking and cycling. In places we also propose to develop cultural spaces. Public use will ensure protection of our fragile environment and coastal eco systems. Community vigilance is the best way to achieve this objective.

Depending on the existing condition, we have proposed mud tracks, board walks. Paved walkways are suggested in the making of the promenades on the seafronts of Bandra. These promenades are developed not by infringing eco-sensitive areas but on illegal land filling and dumping grounds.

To: Urmila Rajadhyaksha

The nullah walls and the walkways are both in concrete. These are unsustainable rather, violent interventions in ecological terms.

Unfortunately, we have inherited both these elements as fate accomplice. The Municipal Corporation of the city in its thirst for concrete turn-over, has built reinforced concrete walls on both sides of the water channels – referred to as nullahs, across the city having a total length of more than 200 kms. In places they have also built concrete roads to facilitate movement of JCBs and trucks required for the cleaning of the nullahs.

We have struggled to check further concretization. Our central objective at this point is to expand public spaces in the city. Spaces on both sides of the nullahs are an opportunity which we are developing for walking and cycling. These initiatives are being undertaken through community net-works.

Expanding public spaces in Mumbai is significant under the present situation where the ratio of open spaces is abysmally low. As Mumbai is expanding, its public spaces are shrinking. This is also true for many cities across India.

Though an essential initiative, I think there is a need for a greater understanding of ecological aspects of these natural systems before an intervention is planned. Virtually every edge/interface is treated as a human interface to be accessed by concrete based pathways.

Very interesting in thought but I’m just a bit concerned by the design solutions which seem to focus on large built up interventions especially the nullahs where retaining walls and grass flanked paved walkways are depicted.

Also present rules do not really prioritise which areas a developer should locate RGs in…maybe like proposed roads proposed greenways would help!