descanso gardens

los angeles, california

July 12 to October 12, 2025

in a warming world, shade and the cooling benefits of trees are essential, but not every community has the same access.

shade equity is an issue that disproportionately affects working-class communities, who are more likely to work outdoors, rely on public transportation, and live in denser neighborhoods.

despite this reality, providing shade can be done in simple ways — starting with planting and caring for trees.

views on shade

from the nature of cities

To expand and extend Roots of Cool both geographically and temporally The Nature of Cities asked artists, architects, ecologists, poets, and activists throughout the world this question:

As the world warms up, how are you thinking about the role that trees and shade can play in making your city or region livable?

Enjoy strolling virtually through the twenty four answers we gathered from around the world…

Montreal, Canada

“The true meaning of life is to plant trees under whose shade you do not expect to sit.”

When I think of the role of trees, I think about time. There is a proverb, versions of which I’ve seen attributed to many countries and many people: “A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they shall never sit.” Sometimes the old men are omitted: “The true meaning of life is to plant trees under whose shade you do not expect to sit.”

I’m not sure the author — whoever they really were — meant it to be taken so literally about trees. But this is what I reflect on when I think of shade and livable cities.

I hope that we have the foresight to commit to greening our cities now — including in the hard places, where the concrete is abundant, and the trees are difficult to plant and expensive to maintain — knowing that these trees will grow into essential future infrastructure. Mood boosting infrastructure. Stress reducing infrastructure. Life-prolonging infrastructure.

The climate of our future cities will be fundamentally different than today. I hope the residents of those cities will be able to look back at our decisions with gratitude, from the shady future that we chose to set in motion today.

Carly Ziter

Urban Ecologist, Concordia University, Montreal QC, Canada

Bogotá, Colombia

The chance to hear a bird call during your daily routine, to recognize a tree as a symbol of your neighborhood: a “citizen tree” if you may that shapes identity.

Bogotá, the capital of the páramos — those rugged, low-growing landscapes that serve as powerful water factories for millions — continues to expand often without roots, while at the same time severing the connection between the sky and our soils.

In this context, urban forests must be seen not just as groups of trees, but as families of plants that include shrubs, vines, and ground covers. These communities not only help regulate rising temperatures but can also sustain the habitat and poetry of our non-human neighbors — birds, mammals, pollinators — who are vital in the complex urban dynamic and coexistence with children, women, and our elders among others.

It’s not just about shade or climate comfort, but also about hope and sense of belonging. The chance to hear a bird call during your daily routine, to recognize a tree as a symbol of your neighborhood: a “citizen tree” if you may that shapes identity. Betting on these living landscapes is defending the right to a healthy environment and about understanding the city as a shared and resilient ecosystem.

Diana Wiesner

Landscape Architect, Director, Cerros de Bogotá nonprofit foundation.

Accra, Ghana

Historically, the Shai-Osudoku and the Aburi enclave have dense tree populations and beautiful landscapes, benefiting residents’ mental health.

Trees and shade enhance livability and resilience in cities like Accra, absorbing pollutants and reducing noise pollution. Historically, the Shai-Osudoku and the Aburi enclave have dense tree populations and beautiful landscapes, benefiting residents’ mental health.

However, in recent times increased urbanization and the land tenure system that empowers families and individuals with land ownership make it difficult for government regulation, leading to the indiscriminate felling of trees for housing and real estate development.

Another problem is that the beautiful landscapes in these areas enhance property values economically, leading to an influx of real estate developers who do not take good care of nature and the environment while making their economic gains over the years.

The solution, however, lies in promoting a culture of intolerance for the wanton destruction of nature and a commitment to environmental stewardship.

My organization is committed to promoting tree planting and appreciation of public spaces among children and young adults in the Shai-Osudoku area. This initiative fosters community interactions and social cohesion and promotes public interest in tree maintenance and health. Participation from these groups contributes to a sustainable tree planting culture, making Accra more livable and resilient to climate change.

Ibrahim Wallee

Executive Director, Center for Sustainable Livelihood and Development (CENSLiD)

Accra, Ghana

Portland, Oregon

Heat Amplifies Harm | Tree Shade Can Cool Neighborhoods | Quantifiable

High Fives (And Sevens) For Trees!

Segregation Still | Places with Trees Offer Clues | Poor Folks See Less Green

Heat Amplifies Harm | Tree Shade Can Cool Neighborhoods | Quantifiable

Community Science | Landscape Designs for Good Health | Turn Gray Into Green

Vivek Shandas

Professor of Geography, Portland State University

Consultant, CAPA Strategies

Barcelona, Spain

We are losing an agroforestry management tradition that has, for centuries, stopped forest fires and preserved both tangible and intangible heritage

We face the challenge of preventing the irreversible disappearance of the agroforestry mosaic that has shaped Mediterranean cultures for millennia, where trees and crops are combined, creating a diverse and balanced landscape.

The agroforestry mosaic plays a crucial role as carbon reservoirs, support biodiversity, enhance connectivity between natural areas, regulate climate, mitigate flood effects, serve as buffers against forest fires, provide quality products, generate cultural identity, and offer spaces for health-related activities, leisure, and creative expression.

Furthermore, these landscapes are essential for advancing towards a more responsible, equitable, and healthy model of food consumption.

Given the failure of territorial policies, along with the depopulation and abandonment of rural peripheral areas, population ageing, lack of available housing, and decline in family farming, this landscape is vanishing at an alarming rate. We are losing an agroforestry management tradition that has, for centuries, stopped forest fires and preserved both tangible and intangible heritage, such as seeds and species cultivated over hundreds of years, local gastronomic culture, and a rich popular toponymy.

It is precisely the degradation and impoverishment of this millennia-old landscape structure that significantly depletes our toolkit for addressing the global challenges ahead, starting with climate change.

Pere Sala i Martí

Director, Landscape Observatory of Catalonia, Spain

Bogotá, Colombia

In a tropical city, a well-placed tree can turn a scorching sidewalk into a pleasant path, a forgotten corner into a green sanctuary.

NO AUDIO FILE

Big refrigerators, the Power of Trees in a Tropical City

In the heart of a hot tropical city like Monteria in Colombia, where the sun blazes year-round (30 °C) and concrete and buildings trap the heat, trees are more than just decoration—they are life-savers!

These green giants like Almendros, Samanes, Ceibas offer shade, cool the air, and make urban life bearable. Did you know that a single mature tree can cool the surrounding air by up to 7°C (9°F)? we’ve measured that! That’s a natural air conditioner! And its cheap…

Beyond comfort, trees help fight climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen (One tree can absorb up to 21 kilograms of CO₂ per year). They also reduce noise, filter pollutants, and provide homes for birds, lizards, big Iguanas and so many other wildlife—tiny buildings of biodiversity in a sea of cement.

But perhaps most importantly, trees bring beauty, calm and peace. A walk under leafy canopies can ease stress, lower heart rates, and boost mood. In a tropical city, a well-placed tree can turn a scorching sidewalk into a pleasant path, a forgotten corner into a green sanctuary, Japanese people call it Shinrin-yoku (the shower of forest).

Planting native trees isn’t just an act of urban design—it’s an act of hope. It’s about creating cooler, cleaner, more livable cities for everyone. In the tropics, trees aren’t optional. They are essential allies in our fight against heat and chaos.

Wilson Ramírez

Manager, Nature-based Solutions Center,

Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos at Alexander von Humboldt, Colombia

Catania, Italy

I barely have time to stir from slumber each morning before they are already here … curious creatures.

Curious creatures passing through

I barely have time to stir from slumber each morning before they are already here. I spot more of them coming, each one different, curious creatures. I have a friend in the great forest, and we talk often. Even though he lives far away, I send him my messages through our roots. We whisper from tree to tree, and the message travels fast. In that vast woodland, he meets only a few of them.

Under my branches and leaves, they look happy: safe, they shake off their funny clothes, drink cool water, and sometimes rest for a while if they have the time. I’ve learned they’re just passing through.

What makes them rush so much? I see them hurrying to and from those grey boxes in the distance, tired especially when the sun is bright. We trees love the sun its light makes our leaves shimmer. There’s something about those dull grey boxes that clashes with the sun’s warmth, but the curious creatures haven’t realised it yet. They keep building more boxes, one after another, all pressed together.

Sometimes I see one of my tree friends sprouting among the grey walls, but they don’t stay long. Trees are clever; they have realised that you can’t truly live surrounded by all that grey.

A few days ago, one of those creatures sat beneath my leaves, murmuring into a small, glowing mirror. I heard him speak of abandoning the grey boxes and moving closer to the great forest.

At last, I think he has understood, too.

Lorenzo Corrado Pirosa

Architect & R&D Project Manager Italy, Catania

Bogotá, Colombia & Nairobi, Kenya

You are weary. You offer shelter yet have none of your own. There is no shade for the ones who give it.

You are a Horse Chestnut tree, standing tall and dignified at the heart of Place des Vosges. Your broad canopy offers sanctuary to all: children dart beneath your branches, lovers stretch out on the grass, their arms gently draped around each other. Birds sing in your limbs. Life pulses gently around you — peaceful, full.

But not for long.

For thirteen days this month, the temperature has soared above 30°C. Today, it reaches 39.5°C. Journalists will name it Hot Monday. You, sixty feet of living architecture, feel it all. You thirst. Your roots crave moisture. What to do now?

In a desperate act of survival, you begin to close your stomas to conserve water — but in doing so, you silence your natural ability to cool the air through transpiration.

The city grows hotter. Stifling.

Later, they will count 3,000 lives lost to this heatwave.

You are weary. You offer shelter yet have none of your own. There is no shade for the ones who give it.

I wonder who shelters the trees? These living monuments that ask for nothing yet give us so much. In a world growing ever hotter, what is our role in their survival?

María Angélica Mejía

Regional Curator, The Nature of Cities

Basel, Switzerland

There is deep inequality in climate risk and the cooling benefits that trees provide…

NO AUDIO FILE

I believe that, with apologies to Tom Friedman, we live in a hot, fragmented, and crowded world.

Hot, in the sense that climate change is making heat waves more frequent and more intense. The cooling benefits trees provide will be more important than ever, but we also need to be realistic that the magnitude of cooling that trees can provide is only a fraction of the likely global warming, so trees are a partial solution.

Crowded, in the sense that in this urban century, when urban areas are growing faster than ever before, there will be more people in cities, and more pavement. The urban heat island effect could increase in intensity, and we must carefully design new urban settlements to incorporate trees when we can to avoid making our urban areas even hotter.

Fragmented, in the sense of not “flat” in the way Tom Friedman meant it. There is deep inequality in climate risk and the cooling benefits that trees provide, with richer countries and richer neighborhoods being cooler than poorer countries and poor neighborhoods.

The solution must be focusing efforts to expand tree canopy on places that most need and counteract partially the current profound inequality.

Robert McDonald

Lead Scientist for Nature-based Solutions, The Nature Conservancy, Basel, Switzerland

Bogotá, Colombia

Trees are needed for our spiritual growth, but they’re also needed to cool down the temperatures of our cities, of our planet.

My lifelong question—”What would it feel like to be a tree?”—led me to a Montreal park one vibrant autumn. Amidst the stunning landscape, a magnificent ginkgo at a crossroad caught my eye. Sitting beside it, I closed my eyes and sought permission to connect, imagining a bridge between us.

The connection began with its roots, which I sensed extending far beyond where I sat, reaching in every direction. Then came the trunk, branches, and leaves. A profound feeling of timeless steadiness and magnificence washed over me—something beyond words, yet empowering. I felt powerful, alive, and intensely aware, embodying the beauty of that ginkgo.

Later, I learned ginkgos are among the world’s oldest tree species, making the idea of being the park’s oldest tree even more resonant. This experience highlighted that a “livable city” acknowledges life’s unseen dimensions. It’s not just about visible aspects like leaves or trunk shape, but also the hidden depths of roots and the capacity to adapt through seasons.

Trees are far more than mere decoration. As various cultures affirm, they remind us that life involves planting seeds, embracing transformation, and connecting with impermanence. True steadiness isn’t avoiding change, but enabling it and continuous transformation. Beyond their spiritual significance, trees are vital for cooling cities and the planet, and they provide homes for countless species.

Carolina Figueroa Arango

Political Scientist, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá

The Bronx, New York

Trees in cities do a lot of work. The shade they cast is a special kind of shade, different from the hard lines cast by buildings. Tree shade moves and breathes.

Sunlight dances on the sidewalk in the summer. And in the winter, when we need more warmth, the trees adjust by dropping their leaves. And tree shade also has a sound, it catches the breeze and softens the aggressive edges of cars, trains, alarms and other urban noise. Not to mention the occasional bird singing overhead. And tree shade changes color; it flowers in the spring and bursts with warmth in the fall. It also smells, sometimes subtle, sometimes fragrant, but usually delightful. Trees in cities also require care, we must think of their well-being, water them, prune them, and with these acts, we connect to nature in a very direct way.

Matthew López-Jensen

Artist, The Bronx

San Francisco, California

As the world warms, trees and shade become vital allies in making cities livable — but their role extends beyond cooling.

At the Environmental Performance Agency, we advocate for reciprocity: caring for more-than-human communities, even those located on the margins especially those impacted by climate disruption and urbanization. Trees and their vegetal kin sustain us — cleaning air, soil, and water — yet their underground networks reveal even deeper connections.

As Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, “In some native languages, the term for plants translates to ‘Those who take care of us.’” But to truly understand, we must look belowground, where fungi and roots forge cross-species alliances. These hidden mycelial networks enable trees to withstand urban stresses, offering shade not just to humans but to entire ecosystems. In damaged landscapes, such relationships thrive amid weeds and “novel ecologies,” quietly repairing Anthropocenic scars.

This is the Planthroposcene: an era sustained by plants. To act, we must reimagine the plantbodyhumanbody as a collective space — learning through movement and kinesthetic, multispecies fieldwork. Shade isn’t merely relief; it’s a testament to entanglement. By noticing and nurturing these bonds, we can transform cities into resilient, ruderal carescapes.

Christopher Kennedy

Research Scientist (Urban Ecology), Urban Systems Lab at The New School, San Francisco, CA

New York City, New York

In the rapidly changing Arctic, the shifting world of birch trees offers a profound warning about our interconnected future.

Today I sat in a boreal forest in the arctic. This forest was primarily birch trees, growing at every angle imaginable. These trees very slowly tilt and fall over years, their stillness full of movement. Here in Alaska, permafrost is thawing rapidly, and the stability of the land is shifting beneath these trees. As a visual and sound artist, I’m recording and documenting what they look like and recording their subsurface sounds. Over the past seven years, I have been capturing their interior sonic landscape.

In urban neighborhoods, like the one I live in in Brooklyn, trees are often praised for the shade they give—cooling sidewalks, dampening noise, cleaning air. Out here, where few people walk, trees are part of something deeper going on. They hold memory. Their disorienting tilting and collapsing structure is not only a disruption of the shade they give the forest floor in the summer but a warning from the ecosystem itself. The line between city and wilderness is thinner than we think.

As the world warms, I think about all trees as living witnesses. Shade in the hot summer months is a gift but also a reminder to listen. To lie under branches and wonder what they’ve seen. To recognize the collapse as both a symptom and a message. What we plant, protect, or ignore now will shape the soundscapes of our shared future.

Nikki Lindt

Artist, New York City

Tongyeong, Korea

Dangsan Namu—ancient guardian trees in the heart many Korean neighborhoods—help us reconnect urban life with nature, and the cosmos.

The wind moves through her, and she waves gently. A shimmering of sunlight moves between her leaves and the ground. Her trunk is several hundred years old, so big it takes several people, hands strung together, to hug her. Seen from afar, people say she looks like a crown of glistening broccoli poking out above rows of rooftops. When one arrives at the courtyard however, it feels more like a cool, peaceful urban altar. According to locals here, it is.

This graceful giant in the middle of a Korean city is both sacred and wise, and the order and decoration of the courtyard where she stands acknowledges this. The people do, too. They tell me this place honors not only the spirit of the tree, but our relationship with nature and the cosmos.

Koreans call this tree a Dangsan Namu — a living guardian of the neighborhood.

Nearly every old neighborhood in the country has one of these trees, sometimes a Ginkgo, or Zelkova, or Camphor, but always appointed by the people who live in the place. If this is true, then there are many would-be, could be, Dangsan Namu in the world.

They are just waiting to be appointed by you and me.

Patrick Lydon

Artist & Writer, Tongyeong, Korea

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Have you ever wondered why people love trees more than other plants? It might go way back—deep in our history.

Trees aren’t just plants; they’re symbols of life, growth, wisdom, and family across many cultures. Some even see them as sacred, tied to spirits or ancestors.

But beyond symbolism, trees offer real, everyday benefits. They fight climate change by absorbing carbon, clean our air, give us shade, block wind, and provide oxygen. Every neighborhood should aim for 30% tree cover—it cools cities, cleans the air, and makes streets more vibrant.

Trees also inspire admiration. Their size, age, and beauty in every season—blossoms in spring, golden fall leaves, snow-covered pines—make them more captivating than grass or flower beds. They humble us, reminding us of nature’s power.

And they’re practical, too. Trees give us wood, fruit, chocolate, cinnamon—the list goes on.

Most importantly, they’re good for our mental health. Just seeing trees from your window or living near green spaces reduces stress and boosts well-being.

Ana Faggi

Ecologist, Flores University, Buenos Aires

Ayrshire, Scotland

There are trees in every direction I look … and pollinators have more places to be busy because of artists.

I’m in London just now and although the neighborhood is very mixed, there are trees in every direction I look. I recently ran across the question. What does a forest planted by an artist look like? Should you be able to tell that it’s art?

With Agnes Denes’ “Forest Mountain”, you know because of the mathematical pattern. With Cathy Fitzgerald’s “Hollywood Forest Story”, you only know because of the stories. With Katie Paterson’s “Future Library”, you only know because of the annual events where writers hand over manuscripts to be published in 100 years on paper made from the trees. With Joseph Beuys’ “7000 Oaks”, you know because of the basalt columns planted with the trees. With David Nash’s “Ash Dome”, you know because of the formal design and the fletching of the trees. Now, you know, because he’s planted a circle of oaks around the dead ash trees. With Helen and Newton Harrison’s “Future Garden”, you only know because of the story and maybe the song, even though the scientists are monitoring the ensemble to see which plants can adapt to the changing climate.

With various orchard projects, including Anne-Marie Culhane’s at Loughborough, and Annie Lord’s in Edinburgh, the pollinators don’t know that their world has more places to be busy because of artists. For resources on artists working with trees and forests please explore the Padlet associated with the newLEAVES network.

Chris Fremantle

Curatorial Research Associate, UFS Arts

Brooklyn, New York

Have you ever wondered why people love trees more than other plants? It might go way back—deep in our history.

When I founded Dlandstudio in 2005, a primary goal was to reconsider relationships among infrastructure, communities, and urban design, aiming to heal injustices and improve urban ecology. Twenty years in, I reflect on society’s relationship to trees in three parts: Trees or infrastructure, trees as infrastructure, and trees an infrastructure.

Often, trees lose out in conflicts with urban infrastructure like roads, sidewalks, and utilities. They are undervalued, their ecological contributions harder to quantify than engineered systems, and are often treated as disposable.

However, in the coming century, trees will be critical infrastructure. As the climate warms, their cooling through evapotranspiration and shading will be essential. Trees absorb water, filter pollutants, and create habitat for diverse species, including humans, providing places for pause and play.

Trees exhibit “crown shyness,” a resilience strategy for light capture, pest reduction, and water distribution. We can optimize these benefits by coordinating trees with grey infrastructure. Urban tree canopy should be a connected system, as groups of trees are more ecologically productive. Integrating trees into urban infrastructure is vital for the 21st-century city.

Susannah C. Drake FASLA FAIA

Landscape Architect and Architect, Brooklyn, NY

Zurich, Switzerland & New York City, New York

A blur of green crossed the street, a forest on wheels. Stopping, starting, bumping along it made its way across the city.

A “Wanderbaumallee” in German. As part of a city climate initiative, young trees were placed within mobile frames to migrate across town, creating spontaneous green spaces as a means of highlighting the need for more trees in the city.

I’ve recently delved into stories of trees as protagonists, myths, and meeting places for my book, A Tree Grows in Queens. We often speak of how trees cool their surroundings, provide shade, and clean the air but we should also include the sense of wonder and awe they inspire. These last two sensations may be more readily available in the “great outdoors” but why not in the city? Why can’t magic and surprise be a part of the urban forest?

And so this funny, festive, joyful procession of trees moving through the city filled me with hope. Trees can spark conversation, brighten a grey city, or cause traffic to slow. Who gets to find comfort under the shifting leaves of a tree? Using creative, surprising, even playful solutions can remind us that anyone can and should be given the chance.

Magali Duzant

Artist & Writer, Zurich & New York

Caulfield, Australia

Urban tree planting must be pragmatic not purist, to create novel ecosystems, drawing on a rich palette of trees

I have often wondered what is meant by ‘livable’? One person’s notion of a livable city might not be that of another, but in its broadest sense a livable city is one that is “suitable or good for living” (Cambridge Dictionary).

For all cities to be livable, trees must be abundant, providing an effective canopy for shade. I recall a time in the not-too-distant past when ‘beautification’ drove tree planting in cities. The value of trees was aesthetic or for amenity. Move forward to today and biophilia and biodiversity are the two ‘b’ words driving tree planting. The appearance of the trees is still important but so too is their contribution to an urban landscape that enhances human well-being through its ecosystem services and functions as habitat for wildlife.

Ideally, urban trees will be indigenous but this is a challenge in Australia where most indigenous trees are evergreen. Shade is important in summer but in winter we love to see and feel the sun. Urban tree planting must be pragmatic not purist, to create novel ecosystems, drawing on a rich palette of trees that will survive the harsh urban conditions to give us humans summer shade and winter delight.

Dr Meredith Dobbie

Landscape Architect and Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, MADA, Informal Cities Lab – Revitalising Informal Settlements and Their Environments, Monash University, Caulfield, Victoria, Australia

Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

Urban forests are important parts of city planning, not just for the environment, but for public health and infrastructure.

NO AUDIO FILE

Nature-based solutions (NbS) are actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems that address societal challenges. Urban forests when understood to be the combination of all woody vegetation within and close to the urban area are already acting as a nature-based solution. However, management of the urban forest can be optimized to if nature-based benefits are the key objective.

In a recently completed five-year study undertaken between Europe and China these management enhancements were investigated. The key finding was that ecosystem services management of the urban forest should take precedence over managing risk and aesthetics. For example, the importance of the soil in the root zone of trees and the need to give the highest priority of protection to existing mature trees were highlighted.

There is also a key role in urban planning especially in the relationship between developers and regulators. Developers should encourage close to nature living in their developments and regulators should ensure that developers enter legally binding ordinances to protect existing mature trees. City authorities should also ensure that the urban forest is featured in city development plans not just in the environment section but also in public health, infrastructure and city zoning.

Other beneficial actions include encouragement of microhabitats on trees which provide an increased number of living spaces for a vast variety of organisms, including pollinating insects. Cities that have urban brownfields should also consider these as a strategic ecosystem resource where tree planting and management of naturally regenerating vegetation creates ecological connectivity and extends existing green infrastructure corridors.

Clive Davies

Chair of Board of Directors, European Forum on Urban Forestry

Mumbai, India

We are dealing with immeasurable stresses in daily life — physical as well as sensorial. Trees offer relief.

Relief.

Trees hold stable the earth below our feet. Canopies capture rain, and avoid run off into our strained drainage systems. Trees can reduce surface temperatures by 8 degrees in cities that are battered by increasing and dangerous heat-island effects. They add a sense of a human scale to city spaces. We are dealing with immeasurable stresses in daily life — physical as well as sensorial. Trees offer relief — in shade, from noise, dust and heat. Most importantly, trees are a visual delight, swaying branches and green leaves offer a softness amidst our overly built cityscapes.

Relief.

Tree cover, shade and the naturally cooling presence of urban greens are things that we need, but are often left yearning.

We must rally to protect and enhance city forests to counter our overly built environments — to sustain a better quality of life for our future generations. Trees must be integral to cityscapes — not used merely as decorative features. Rather, they must be planted in groves and clusters that promote the concepts of city forests and linear tree covered parks that will ensure a decentralised approach towards urban greening – an effort to provide more comfortable urbanscapes for people to inhabit.

Samarth Das

Architect, Urban Designer

Design Lead at PKDA Architects, Mumbai

New York City, New York

In caring for trees, we express our care and concern for each other. We need those expressions of care all the more…

Trees are critical infrastructure for our cities and towns. They provide shade, cooling, water retention, habitat, and beauty – all essential functions for making our places liveable for humans and nonhumans. This is now conventional wisdom in urban forestry and city planning, and it is true.

But does calling trees infrastructure minimize that they are also living beings? What can we learn from being in relation to these beings that are adapted to exist in such a wide range of settings — from mountainsides, to coastal floodplains, to urban streets? They are our constant companions — exchanging Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide with us. They help us mark time – cyclical time through seasonal changes of bud, bloom, leaf out, leaf drop, and dormancy – and linear time as they emerge, grow, senesce, and die. We honor our dead and our historic events through commemorative acts of planting and care. In caring for trees, we express our care and concern for each other. We need those expressions of care and the bonds that they strengthen all the more as we enter a much more irregular, erratic, and disrupted climate and world.

Lindsay K. Campbell

Human Geographer, New York, NY

Paris, France

A squirrel crosses the park’s avenue

Climbs on a tree, a soft spot,

Fresh, protected,

In the ocean of heat

That is now the city

Excerpt from a poem by Carmen Bouyer

Shade is everywhere

It’s night time

We sleep in the shadow of the Earth

Its thick dark blanket protecting our dreams

Velvet cool air

The sun is rising

Slowing painting the rocks and the high leaves

With its pink and golden rays

Pavement is still fresh like the night air

Birds are singing now, joyously welcoming a new day

Cars, more and more numerous,

Are starting over their relentless ballet

In the bright morning, warmth is already here

Time to turn on the AC and your favorite radio show

Inside the car

Coffee time and the sun is already high

It’s summer

A time when our astral fire rises higher

Faster it seems

Towards its zenith

Sidewalks are now fully lit

Asphalt starts to tremble

Slowly, softly, then more wildly

Creating zones of visual hallucinations

Portals to ever dry oceans

A squirrel crosses the park’s avenue

Climbs on a tree, a soft spot,

Fresh, protected,

In the ocean of heat

That is now the city

Carmen Bouyer

Artist, Paris

Rome, Italy

After years of studying and working with trees, you’d think I’d be used to them. But honestly, they still surprise me.

I’ll give you an example.

One blistering afternoon last summer, I was walking through a dense part of the city—heat bouncing off glass and pavement, air thick enough to wear. Then I turned a corner onto a tree-lined street, and it was like stepping into another world. The air changed. It was cooler, quieter. The leaves above were doing their work—shading, breathing, transforming the space around them. And I remember thinking: this is what resilience looks like.

Urban trees aren’t just pleasant extras. They are living infrastructure—carbon sinks, cooling systems, stormwater managers. A single mature tree can store over 20 kilograms of carbon each year, intercept rainfall, filter pollutants, and create a microclimate that supports people, pollinators, and even soil health.

But beyond the data—beyond the charts and figures I’ve worked with for years—there’s something almost magical about what trees do in cities. They turn stress into calm. Heat into breath. Concrete jungles into places you want to stay.

In the face of climate change, we need solutions that work—and trees do. But we also need solutions that inspire. And trees do that, too.

Simone Borelli

Retired Agroforestry and Urban Forestry Officer, UN FAO, Rome

Charlottesville, Virginia

There is a towering and majestic tulip poplar that I pass by everyday. I whisper a hello to her as I touch her deep furrowed bark.

There are many large trees that pass everyday in my home city. They are to me spectacular, beautiful, an embodiment of life optimism in bark and leaf form; their skyward branches and deep roots are what hold communities together, literally, and they add a dose of delight and uplift to every single day of my life. There is a towering and majestic tulip poplar, likely a 100-years old at least, that I pass by everyday. I whisper a hello to her as I pass by and touch her deep furrowed bark.

The shade these large trees provide is of course immense, and during hot Virginia’s summers trees make it possible to live a truly human life outside. Without their shade and evopotranspiration it is often so hot that it feels like attempting to walk on the moon without a spacesuit. They are home to many birds and other nonhuman species. Without these trees there would be little birdsong in my city (or any city) to enjoy. Yet we’re losing many older trees in cities and they are often viewed as of secondary importance and expendable (something barely on a par with street furniture.

We need to do many things to support the trees around us. We need to give them names where we can and talk about them in ways that convey the power and personal affection we have for them. We need to draw them and write poems about them and talk about the beauty they bring to our lives. We need to make clear that we consider them part of our community. We of course need strong tree codes that ensure that trees are not lost or removed for frivolous reasons and that acknowledge the many public benefits they provide (including shade and “coolth”) but also their intrinsic moral worth. We need increasingly to understand them as complex, sentient creatures (as forest ecologist Suzanne Simard argues). We need to change our fiscal systems to reward the protection of existing older trees in cities–lower property taxes where trees are protected and cared for, higher where they are unnecessarily sacrificed. And we need to stand up for them and give them a voice where we can (and for the countless birds and nonhuman life harmed when older trees are removed). Ultimately we need a tree-centric (and nature-centric) politics where future mayors, council members and planning commissioners campaign for their positions by standing up for trees.

Tim Beatley

Professor of Sustainable Communities, University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Berlin, Germany

Trees could turn our cities into gardens. They could turn our cities into paradise.

Just imagine a city with a dense tree cover, with shrubs and green in the shade. Like in a garden. But before, humans need to know that they can live in paradise when they want.

There are three trees in my back garden dying of the worst drought for ninety years in Germany. And I have made myself shouted at by neighbours when I gave them water.

There are people who don’t want to live in paradise and who don’t want others to live in paradise. And this is a practical problem.

Andreas Weber

Biologist, Philosopher, Nature Writer

Berlin, Germany & Varese Ligure, Italy

descanso gardens

los angeles, california

July 12 to October 12, 2025

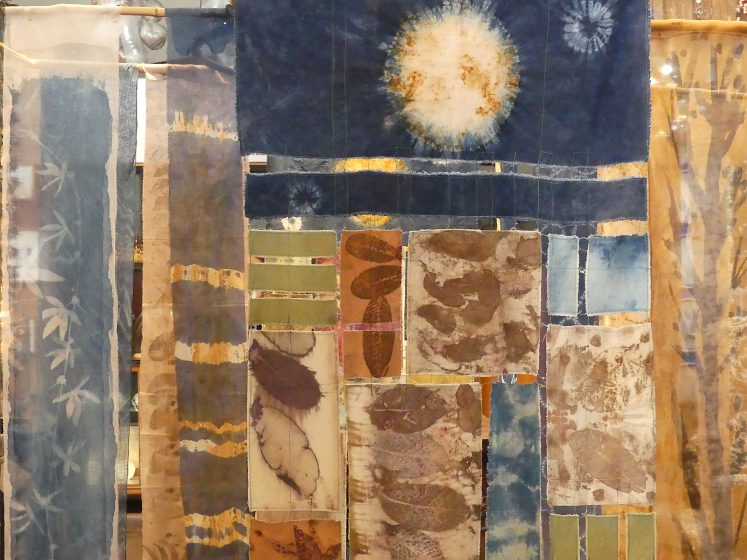

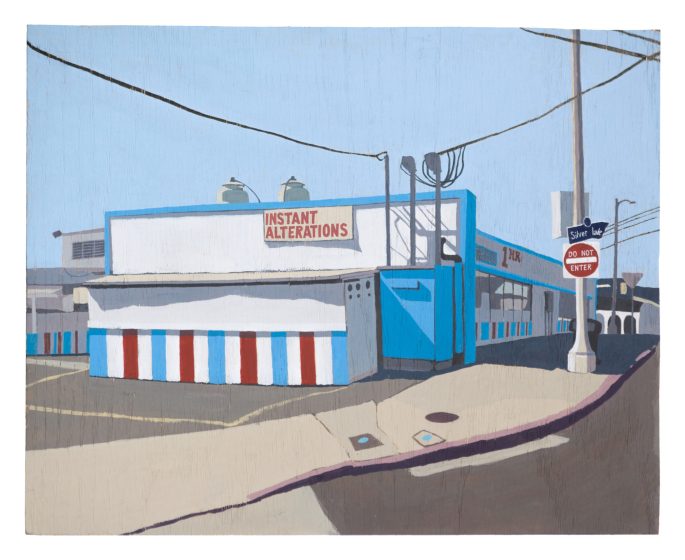

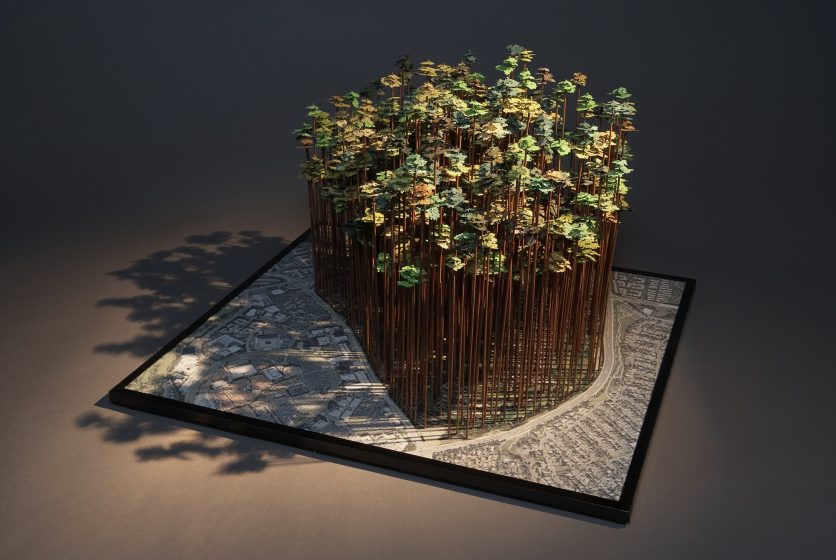

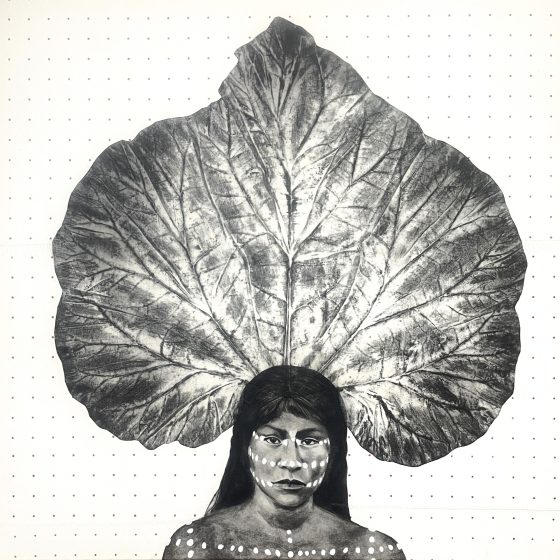

Thirteen women artists plus the Yarn Bombing Los Angeles collective explore the past, present, and future role of trees and shade in the city, with visual and musical works to inspire us to collectively imagine a cooler, greener future. The only way to get there is to train our eyes to see opportunities in our neighborhoods to make change, and then roll up our sleeves and make it happen.We each have more power than we realize.

We are rooted in the past. We are rooting for the future.

on urban trees:

MORE WRITINGS from the nature of cities

shade in action:

explore shade-related projects from the nature of cities

EXHIBITION

shade in the city

rising heat and inequity in a sunburnt era

ECO-POETRY

SPROUT POETRY JOURNAL

ISSUE 3: shade

Produced by

The Nature of Cities

for

Roots of Cool

and

Descanso Gardens