“Speed is irrelevant if you are going in the wrong direction”

— M K Gandhi

Will we have enough resources to consume and survive if 60% of the world’s population becomes urbanized by 2030? Are our cities self-sufficient entities? How are we going to satisfy the huge appetite of the growing cities and still be able the leave a livable world for our future? Two per cent (2%) of the world’s land surface, which the cities currently occupy, consumes 75% of the world’s natural resources and discharges an equal amount of waste, causing huge ecological footprints.

“We are using 50 per cent more resources than the Earth can provide. By 2030, even two planets will not be enough” (Living Planet Report 2012, WWF).

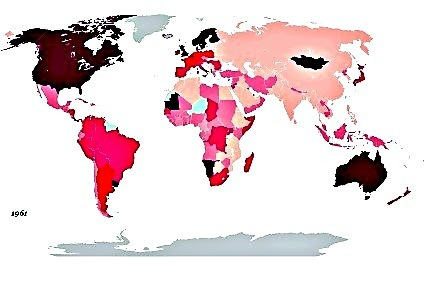

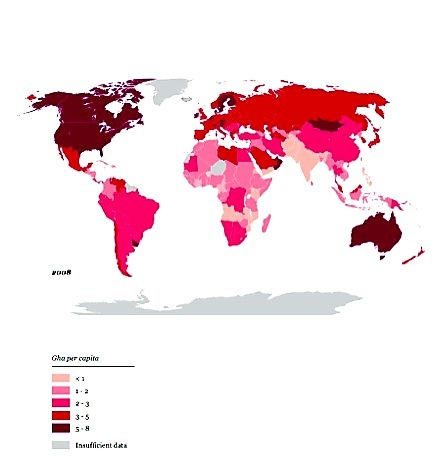

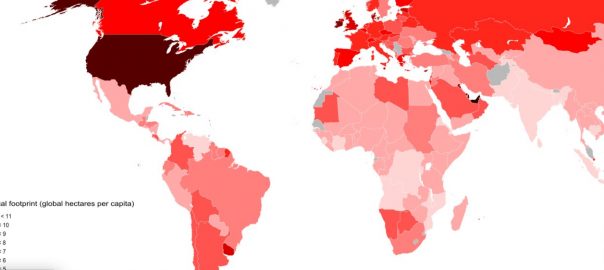

“Ecological footprint”, a term coined by Rees and Wackernagel in 1992, uses land as currency to measure what we have and what our demands are and how our activities impact nature. It measures the land resources required to support the current consumption levels with current levels of technology for supporting our food consumption, housing, transport and waste production. It is measured in so-called global hectares (GHA), defined as the average productivity of all biologically productive areas (measured in hectares) on earth in a given year. The figures above show how much ecological footprints have increased between the years 1961 and 2008. Against an estimated biocapacity of our planet of 1.87 hectares (per person) — as estimated by Wackernagel et al. (1999) — the average ecological footprint is now 2.2 Gha.

The point of debate in this note is not which country has larger ecological footprints, but rather to point out the fact that cities have large footprints and if we do not curb our footprint it would pose a huge challenge for the policy makers and public. The Future We Want, an outcome document at Rio+20, acknowledged that we must recognize the interlinkages among the three dimensions of sustainability and develop various tools and approaches to measure sustainability in a way that can support growth as well as health of the ecosystems.

The key question is: what are the possible ways to ensure that we bequeath a sustainable planet to our future generations? Some of the solutions proposed in various international debates and fora are:

(1) Reduce the ecological footprints by promoting conservation and sustainable use.

(2) Promote green economies, which would reduce negative environmental impacts, increase resource efficiency and reduce waste.

(3) Engage all the stakeholders of the society — the people, governments, civil society and private sector — in the job of achieving urban sustainability.

The prime thing is to reduce our ecological footprints. The ecologists, conservationists, architects and designers all have proposed several alternatives, such as adopting a landscape management approach to improve connectivity between ecosystem fragments, leaving ecosystems undisturbed, planting native species, controlling invasive species and ensuring ecological succession. These are necessary but not sufficient to bequeath a sustainable earth. Policy makers have a huge role to play to tackle environmental and social issues towards facilitating public acceptance towards naturalistic habitats in urban areas.

I am not advocating that we use a particular measure to see how damaging our activities are. Each approach offers its unique advantages and suffers from limitations. One could use various measurable indicators and environmental planning tools to know where we are heading and how to manage our resources, such as carbon footprints, Biodiversity indices for Cities, ecoBudgets, etc. These indicators are like lists, as pointed out by David Maddox in his earlier essay. Everybody likes to be on the top of the good lists (like clean, green, wealthy) and bottom of ‘bad’ lists (carbon, ecological, water footprints etc.). These lists are useful for managing our environment using different environment management tools like Integrated Management systems, Local Agenda 21, ISO 14001, European Environment Management systems etc, to know where we are heading and how to manage our resources. As mentioned, the applicability of these tools and indicators varies as the situation warrants.

We need to learn from each other’s experiences as even a tiny footstep can go a long way in reducing our ecological footprint. Earlier writers in this series comprising a mix of scientists, designers and practitioners shared their views and showcased successful examples on how we can make “livable ecological spaces”. The UN report on “The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity”, launched at the Convention of Biodiversity-Conference of Parties 10 held at Nagoya, reviewed some successful initiatives at international, national, sub-national, local levels, business and citizens.

Some initiatives which policy makers can take up: create green networks with green belts; arrest urban sprawl through city zoning; promote low energy housing and efficient public transports; develop private green spaces; green rooftops, community gardens, green walls and put more solar plants; and citizens can try and reduce and recycle the waste generation and water use, build green rooftops etc. — all very important initiatives for a green tomorrow.

We also need strong incentives and disincentives to induce change in our behavior. Some ways of modifying citizen’s behaviour include: imposing penalties for consuming more land; promoting bonus and off-setting schemes to compensate for the negative impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems; giving financial incentive to reduce waste through “pay-as-you throw”. Local governments must also assume a regulatory role through imposing building codes for impacts on land/landscape due to construction, regulate waste through promoting polluter-pays principle, impose no vehicle zones to encourage pedestrians and cyclists to suggest some.

Yes, we have promising solutions and possibilities for efficient utilization of resources due to the concentrated nature of demand and supply of cities. I have two examples from Maharashtra to support that recognizing the nature’s values can put nature back in our cities.

The first example shows how the land crunched city of Mumbai tried to increase the retention capacity of the land, which has exceeded its biocapacity — a step forward in reducing the impact that we have created on environment due to our activities. The second example, though not from a city setting, shows how a visionary village which lived above its biocapacity recognized the important role of natural resources management and adopted an integrated model of development, to turn people from abrupt poverty to millionaires.

As urban citizens we need to understand that a ‘magic wand’ does not exist to meet our consumption needs, but comes from nature, and our actions impact nature, which can boomerang. We have lessons to learn from not only these examples but from all over the world.

Example 1: Maharashtra National Park

The first example is the Maharashtra Nature Park, also known as Mahim Nature Park in Mumbai covers an area of 37 acres. The park is situated next to Asia’s largest slum, Dharavi. No one would believe that this lush green forest was created on a five-meter deep garbage dump 20 years ago. This Mahim Natural Park, as a result of the efforts of Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF India), who wanted to tackle pollution in garbage dump and create a much-needed green lung for the city of Mumbai.

Now the park attracts 38 species of butterflies, 80 species of birds, have around 13.500 varieties of species, many insects, reptiles and amphibians. The initiative shows how we can put back nature on a system, which exceeded its biocapacity. Instead of shifting all the filth to some other city or place and damaging the ecosystem further, the effort has resulted in bring back ‘green spaces’, an effort to reduce the ecological footprint of the city of Mumbai.

Example 2: Hiware Bazar in Maharashtra

Hiware Bazar in Maharashtra is a semi-arid village that from 1970s to 1990s ran out of most of its natural assets. The village faced an acute water crisis as a result of which during 1989-90, only 12% of the land was cultivated resulting in rampant poverty in the region. A number of youth migrated out of the village. In 1990s a visionary leader Popatrao Pawar adopted integrated model of development with water conservation at its core by adopting the following five principles: (1) a ban on liquor, (2) an ban on cutting trees, (3) elimination of free grazing, (4) family planning, and (5) contributing village labour for development work.

During 1995-2000 the village specially targeted ecological regeneration and also took advantage of the Employment Guarantee scheme to regenerate degraded village forests and catchments and to restore watershed ecosystem. The villagers resorted to various watershed conservation techniques like contour trenching and bunding, tree plantation, rainwater harvesting, recharge of ground waters. The irrigation was mainly carried out through drip irrigation, open irrigation and with minimum use of ground water.

Today the per capita income of the village is twice the average of the top 10 per cent in rural areas nationwide. Since 2002, Hiware Bazar is doing an annual budgeting of water, wherein the total amount of water available in the village is measured, uses estimated and then agricultural cropping taken up as prescribed. The Village council’s decisions are binding. Water for drinking purposes (of humans and animals) and for other daily uses gets top priority. Of the remaining water, 70% is reserved for irrigation and 30% is stored for future use by allowing it to percolate and recharge groundwater. Taking this broad framework for water use, a yearly audit is carried out to assess the water available and adjust its usage.

To Conclude

We need to urgently look for doable solutions that can change our lifestyles before it becomes impossible. We cannot wait for a huge revolution to happen. Our footprint is going to get larger but before nature puts a ‘natural end’ to this (Hurricane Sandy, Hurricane Katrina, Cyclone Aila, Massive earthquakes and Tsunamis in Japan, New Zealand, Haiti, Yangtze river floods) we need to act. Recognizing, demonstrating and capturing the value of various ecosystem services and the benefits that they provide to human well-being is a first step to protect our natural resources. We need to get out of our materialistic thinking with “production and consumption” at the centre.

There is a very crucial role that all the policy makers and citizens can play in achieving this goal of reducing the ecological footprints a move towards sustainability. Small footsteps taken by all of us towards achieving the common goal can become a “giant footprint” enough to bequeath as livable planet for our future generations.

Haripriya Gunimeda

Mumbai, India

References:

- TEEBcase on Hiware Bazaar – Enhancing agriculture by ecosystem management

- Sakhuja, N. 2008, ‘Hiware Bazar- A village with 54 millionaires’, Down to Earth vol: 16 no: 20080131

- Wackernagel, M., Onisto, L., Bello, P., Linares, A. C., Falfan, I. S. L., Garcia, J. M., Guerrero, A. I. S. and Guerrero, C. S.:1999. “National natural capital accounting with the ecological footprint concept.” Ecological Economics 29(3): 375−390.

About the Writer:

Haripriya Gundimeda

Dr. Gundimeda is a Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay; and the President of URBIO. Her main interests are green accounting, mitigation aspects of climate change, energy demand and pricing, valuation of environmental resources, and issues relating to the development in India.

11 Comments

Join our conversation