Today I would like to celebrate the First Congress of the Society for Urban Ecology (SURE), which took place at the end of July in Berlin, just in the place where urban ecology emerged as a discipline. And also I’ll consider what our discipline of urban ecology has to say to people in cities such as Berlin and my hometown, Buenos Aires.

The conference brought together more than 300 people from different continents, who spoke in keynote presentations and symposia. It was an encouraging opportunity to meet old friends, members of The Nature of Cities blog who only knew each other through their posted essays, and also some Urban Ecology “celebrities” (those famous guys of the literature).

Twenty-five speakers participated in the symposium entitled “The Nature of Cities: The diverse roots of coupled social-ecological research that leads to design of urban environments” giving credit to the excellent idea conceived one year ago by David Maddox, encouraging readers to reconnect to nature and to think about the necessity to maintain urban nature and biodiversity.

The conference reinforced ideas that have been discussed in the last decades in the context of disciplines like Urban and Landscape Ecology, Geography, Landscape Architecture, Urbanism, Sociology, among others, showing that cities are complex socio-techno-ecological systems impacted by external drivers at different scales (as discussed by Nancy Grimm). That each city has a distinctive cultural heritage, development history, planning tradition and social structure, offering at the same time opportunities to reimagine and reinvent a sustainable future for all species (Thomas Elmqvist).

As expected in times of climate and demographic change, special attention was placed on the relevance to livability, resilience and sustainability of green and blue infrastructure in densely built-up areas (Giovanni Sanesi). As many presentations showed, investments in such infrastructure represent win-win ways to reconcile urbanization with the protection of ecosystems, landscape ecological functions and processes (Cecilia Herzog).

Nonetheless, other evidence showed that in many cases urban park designs frequently do not reflect the necessary full spectrum of ecosystem services that we care about considering needs, values and perceptions (Jürgen Breuste) and that global trends in urban design and planning are responsible for sadly homogenous flora in gardens across latitudes, when in fact native plantings would easily support biodiversity and be more locally relevant (Maria Ignatieva).

The Congress’ message was this: people want cities that are livable, resilient and smart (Christiane Weber), in which they can appreciate, be aware and celebrate worthy things. What works in nature to produce healthy and resilient systems? What works in communities of people to make heathy and livable cities? Let’s (re)discover these things and apply them in our cities and towns. Wei-Ning Xiang offered useful advice in a keynote presentation: learn from the past. This is a fundamental principle in all ecological restoration projects!

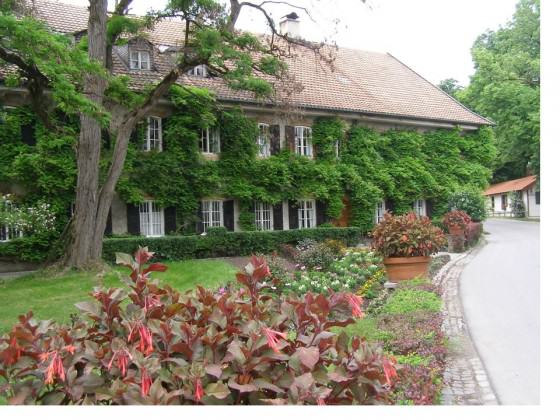

At the end of the day, on the way to my accommodation in the Steglitz neighborhood, I tried to recognize in the urban matrix of Berlin evidence of our discussions during the conference. They were hot days and suburban train travellers showed signs of climate discomfort, showing the importance of the urban green and the need of improvements in transport conditions in the heat waves that are likely to be more frequent. Such simple things as windows that would open, makes us realize that good design is secured by cultural norms and at the same time by environmental realities and imagination. On the other hand, the massive turnout of people in the parks and lakes in the late afternoons confirmed how they profit from the existing green and blue infrastructure within the city. The appearance of mammals — a fox between parked cars, squirrels and porcupines in a front garden — was to me a sign of a livable, green Berlin unlike the everyday in the Buenos Aires metropolis, where I live.

Buenos Aires is a good example demonstrating that cities are products of history and therefore socially conditioned. The European immigration in the late 19th century shaped the city. Today we can recognise the Spanish and Italian Heritage in the city grid and design and, at the same time, the French and English influence in the signature of green areas.

The city has a high population density, which comes at the expense of green space — just 6 square metres of green space per person within the city area. In trying to regreen the city, today the local government is revitalising green spaces, creating at the same time a network of green corridors with bicycle lanes that connect parks, plazas, the waterfront and an urban ecological reserve.

This reserve is an important focus for environmental conservation and education downtown and resembles the conservation area Schöneberger Südgelände, one of the excursion destinations offered during the SURE conference.

In Buenos Aires the 370 hectares reclaimed from the river were very soon spontaneously colonized by humid forests, grasslands, scrublands and wetlands. The new landscape offered shelter and food to many bird species and other animals. By the early 1980s the lagoons and grasslands attracted the attention of bird watchers and the place also became a meeting point for joggers, cyclists, students and naturalists. In 1986, the City Council granted protection to the area in response to claims from many local Non-Governmental Organizations. Since 2005 the natural reserve “Costanera Sur” is included in the Ramsar list of important wetlands for bird conservation.

On the majority of the Schöneberger Südgelände site, also natural development began to take place, which, by 1981, had led to a richly structured mosaic of dry grasslands, tall herbs, shrub vegetation and individual woodlands, then for over four decades an almost untouched new wilderness (Kowarik & Lager 2005).

The Buenos Aires ecological reserve, on the other hand, is a landfill area created in the La Plata estuary using the Dutch “polder” system, which was invented in 1978. A few blocks away from downtown, the embankments were built with demolition materials brought from highway construction works. The polders were filled with silt and sand from the river and drained. However, as in the Schöneberger Südgelände in Berlin, the area was abandoned and the spontaneous sucession resulted in an extraordinary urban wilderness. In both brownfields regeneration areas, visitors are surprised at the beauty of spontaneous vegetation and the force of Nature in reconquering land.

Both cases are good triggers for debate, especially talking about restoration in complex socio-techno-ecological systems as cities are. Ecological restoration is defined by the process of repairing damage caused by humans to the diversity and dynamics of native ecosystems. What is going on in the new urban wilderness is more inclusive, covering reclamation projects, replacements, ecosystem creation and naturalized areas. In general, the challenges of restoration are difficult if not impossible; this is particularly true in cities where the intentional ecological manipulation of ecosystems is subject to variables that go beyond the ecological understanding.

Schöneberger Südgelände is an example of a brownfield reclamation; Costanera Reserve of the creation of a terrestrial ecosystem in a river bed. Both areas have received relatively little systematic stewardship and have become, over time, naturalized. Both are threatened or — depending our values and perceptions — modified by invasions, and are living examples of the New Nature in cities. As exemplary biodiversity urban bastions they mirror the stories that gave them life.

In many ways, they show us that we are living in a new time, where old assumptions — including the ecological ones but also societal choices — must be reconsidered, looking for a compromise in restoration projects where the main objectives should be to improve ecosystem services while reconnecting people with local, native, and spontaneous nature.

Ana Faggi

Buenos Aires

About the Writer:

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

I am studying at Cambridge University in UK, and carrying out a study for my 3rd year dissertation on people’s perceptions of Urban Wilderness in Berlin. Do any statistics exist that have identified this or the value people place on such areas (I guess as apposed to ‘green spaces’ eg managed parks and recreational areas). Anything connected with this would be valuable.

It is an extremely interesting area particularly as here in the UK pressure for urban housing development is acute, and the role of green infrastructure in sustainable development is paramount to the biodiversity and health of our cities.