A review of The Revolutionary Urbanism of Street Farm: Eco-Anarchism, Architecture and Alternative Technology in the 1970s, by Stephen E. Hunt. 2014. ISBN 978-1-906477-44-8. Tangent Books, Bristol. 246 pages, including 16 pages of illustrations.

Visions of cities draped in vegetation are now de rigueur for any architect, planner or urbanist who wants to lay claim to any kind of green mantle. But in the early 1970s—when environmentalism had no eye to the city except to see it as an abomination—and demands for insulation and double glazing in buildings was challenging the conceptual comfort zone of the average architect, the Street Farm vision was almost obscenely green. They wanted to plough the streets! To transform banal highrise office towers into fantastical forms consumed by vegetation gone wild! As an architecture student at the time, I loved it! And, I confess, I still do, so news of this book and the opportunity to make a small contribution to it rekindled all that old excitement. Reading the book caused the flames to rise again.

Author Stephen Hunt is from a humanities background and isn’t trained in architecture or planning—or ecology. His specialism is radical history, and this book records just that: a radical history of some of the most influential pioneers in the field of what the protagonists themselves called ‘revolutionary urbanism.’ Noting that ‘Radical history learns from the past to inform the present and inspire the struggle for the future,’ Hunt saw his project as ‘an unparalleled opportunity to look at the ideas of a unique grassroots activist group and to help understand the intersection between alternative architecture, the counterculture and the ecology movement in the 1970s.’

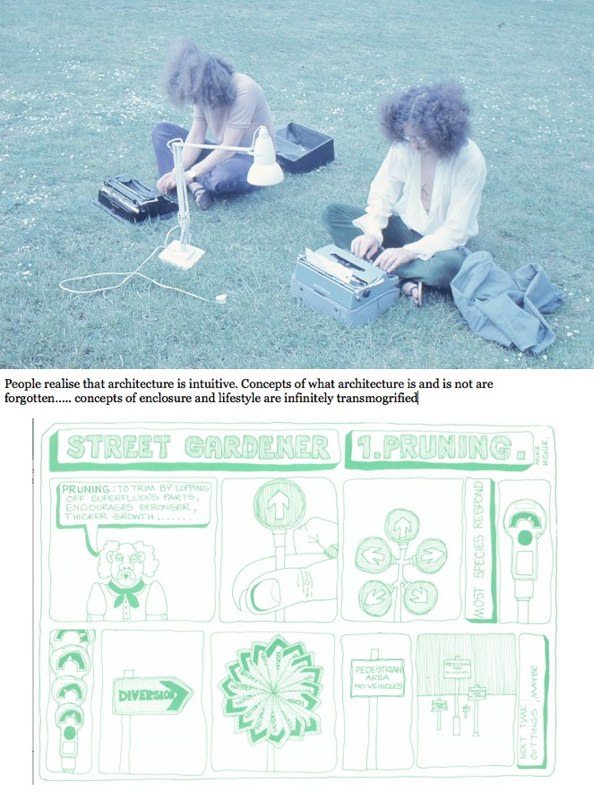

Hunt is an advocate of oral-history interviews ‘as a method for revealing the overlooked experiences of unofficialdom,’ and was keen to capture directly remembered experiences of a part of a remarkable period in western cultural history. It was the time of the first Club of Rome report on Limits to Growth. The Internet had barely been invented, photocopiers had barely begun to have an impact and mechanical typewriters were the norm. It was a time of foment and the atmosphere in the student world was febrile and charged with the idea that radical, creative political change was not only necessary, but possible. It can be difficult, now, to appreciate the disenchantment felt by young people about the state of the world at that time. Paris had undergone near-revolutionary uprisings in 1968. The shadow of the atom bomb stretched across the entire political landscape. Environmental concerns were making headlines and affecting public discourse for the first time. ‘The Limits to Growth’ was published in 1972, the same year Street Farmhouse was built (and both predated the 1973 ‘Oil Crisis’).

There are now twice as many people on the planet, energy costs have continued to rise and the planet’s tree cover has halved, but almost every new architectural project claims to be ‘sustainable.’ The term has usurped ‘ecological,’ but I would argue that the latter contains more meaning, as it embraces the language of living systems. Hunt tells us that a flag with a clenched green fist flew from the top of the polyhedral greenhouse which was part of Graham Caine’s Street Farmhouse, built after securing temporary planning permission on the playing fields of Thames Polytechnic in Eltham, London, by Caine and friends between September and December 1972. The project ‘hit national and international headlines as the first structure intentionally constructed as an ecological house.’ It was the first time the term ‘Ecological House’ had been applied to a dwelling. It has had enduring influence on people such as eco-architecture pioneers Brenda and Robert Vale—and myself.

Caine was supported in his endeavours by Alvin Boyarsky in his role as chair of the Architectural Association, a school of architecture known for both the high quality of its programs and for possessing a long and illustrious tradition of supporting radical and challenging ideas in architecture and design. Begun when he was age 26, Caine and his partner lived in the house for the two years while Caine still a student. He later abandoned pursuit of an architectural qualification in favour of ‘pursuing the betterment of the planet’—one reason, perhaps, that he is not in the notable alumni list in the Architectural Association’s Wikipedia entry.

The eco-house was featured in the U.K. magazine ‘Undercurrents’ and in ‘Mother Earth News’ and in various other publications at the time, including the influential counter-cultural book ‘Radical Technology’ (eds. Godfrey Boyle and Peter Harper 1976). Street Farm’s contemporaries included The New Alchemists, ‘fellow anarchists with similar underlying principles,’ who built the Cape Cod Ark Bioshelter in 1976. In conversation with the book’s author, Graham Caine stated that, to him, ‘an ecological house was about a biological system, so it had an ecology going on within it… it was about experiencing yourself as part of nature.’

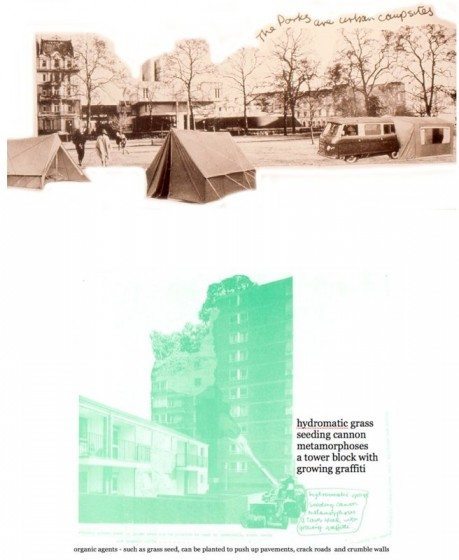

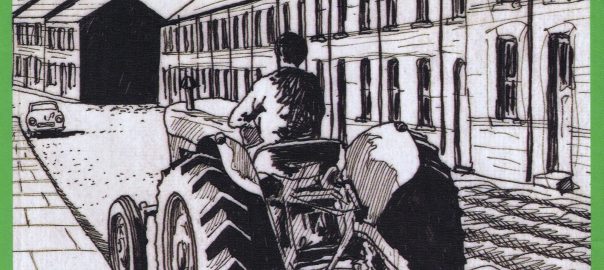

Street Farm formed as a small group of radical, like-minded architecture students—Graham Caine, Peter Crump and Bruce Haggart—who, like Pink Floyd back in the heady days of the late 60s and early 70s, were dissatisfied with the status quo and set out to change it. The ‘Floyd focused on music, the ‘Farm took aim at the largest, most complex creations in the human universe—cities. Placing themselves at the most radical end of the counter-cultural spectrum, Street Farm linked the personal with the political and the philosophical. The spirit of Street Farm was that of the Situationists, one of whose favourite slogans was ‘Be realistic. Demand the impossible!’ In the 1950s, the Situationist International developed ‘Unitary Urbanism,’ a critique of status quo urbanism that informed much of future Situationist thinking and which rejected a functionalist approach to urban architectural design and the compartmentalisation of art away from its surroundings. In Paris in 1968, through slogans and graffiti, these ideas gained a kind of popular currency with widely repeated phrases such as ‘Sous les pavés la plage’ (‘Under the paving, the beach’—which was also a reference to the fact that the cobblestones torn up to be used as weapons against the police in street riots were laid on sand). Such imagery simultaneously reflects the idea of the city as a blanket stifling the natural world, and as a potential place of imagination and liberation. Such powerful themes can be seen in Street Farm’s playful, sometimes deliberately amateurish ‘anti-graphics,’ in which sheep overrun city streets, tractors plough the roads between terraced houses and the ‘urban alchemy’ of creative vandalism leads to streets being transformed into new age villages.

Street Farm rebelled against the system but, because the system is all-embracing and brooks no real escape, they worked within its constraints with sufficient alacrity to deliver genuinely fresh ideas and to produce the first eco-house alongside some of the earliest attempts to reimagine the city as a place of fecund biological activity rather than sterile, technological imagery. Street Farm were the antidote to Archigram, nascent technocrats brewing at the same time in the same school of architecture, who purveyed images of cities as slick, mechanical devices, even walking machines. In an attempt to break down the traditional walls of alienation associated with architecture, Street Farm used multi-media in their presentations at a time when that meant slide projectors and tape recorders. Adopting the roles of entertainers and jesters, they created ragged montage-rich movies and their magazines made extensive use of collage—all to convey the message that architecture and cities could be reclaimed by people through revolutionary direct action, that alienation could be overcome. They drew upon Murray Bookchin and on the Situationist critique of consumerism, the ‘society of the spectacle’ and the potential to remake the urban environment through popular, creative, subversive play.

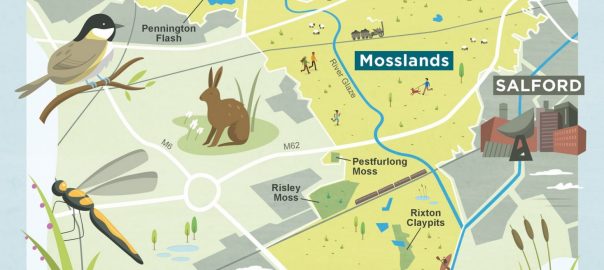

Many strands of environmental concern can be traced back to movements and ideas that arose in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but ‘green urbanism’ is rarely mentioned. The ideas of Street Farm were radical but are now almost routine—every week sees more images of urban buildings splattered and trailing with vegetation in a way that almost mimics the cartooned proposals of Street Farm to simultaneously undermine and remake the city by planting seeds to encourage rampant vegetation. Their vision included planting seeds to change the way living and managing cities took place, as part of a whole remaking of the economic and social order in favour of workers’ control, self-determination and autonomy from the state. At a time when most of the publications of the counter-culture seemed to be all about back-to-the-land romanticism, Street Farmer One proclaimed itself ‘an intermittent continuing manual of alternative urbanism,’ calling out that ‘Spring is here and the time is right for planting in the streets.’ In the ‘road not travelled’ that the counter-culture promised, one can find countless examples of failure, but also examples where it provided the fuel and impetus for changes that have made their way into the DNA of the mainstream. This is one of those examples and it still resonates over four decades later.

Hunt’s interest in the group seems to have been very personal. He was inspired by the need to document the people and ideas that made the counter-cultural 1960s and early 1970s so fecund and fascinating, to show how so much of what we now take for granted in the realm of mainstream ideas can be traced back to initiatives and inventiveness that characterised the best of those years, and to capture something of the spirit and intentions of the times before they melt away into the ether and are lost with the passing of the characters who made it all happen. In this, he has done an excellent job. By concentrating on the activities of a small, almost forgotten group who were extremely active in their day, he provides a snapshot of their concept of ‘revolutionary urbanism’ that delivered ‘a toolbox for practical change’ which could be used in pursuit of the ‘desire for liberation in the nature and quality of our daily lives…and…a transformation of the visual appearance, sound and smell, the texture and ambience of the urban environment’.

Hunt puts it in a nutshell: ‘Taking inspiration from Situationism and social ecology, Street Farm offered a powerful vision of green cities in the control of ordinary people.’ (Think Paris 1968 and anarchist philosopher, later ‘municipal libertarian,’ Murray Bookchin). Their concept of urbanism was about social liberation, but integral to it was ‘a reconsideration of the human relationship with other species and their habitats.’

Street Farm’s narrative consistently advocated an urbanism based on community and, as Hunt observes, were exponents of ‘community architecture’ long before the term was coined. Cities are fundamentally about community and require co-operation and shared endeavour before anything can be built. In many ways, cities are the antithesis of the kind of Ayn Rand individualism that is sometimes mistaken for anarchism. Anarchism is arguably the most misunderstood and maligned of any political philosophy. It conjures up images of chaos, lawlessness and disorder. Although anarchism does mean ‘absence of government,’ it does not mean absence of order, anymore than chaos in nature means there is no order in the patterns assumed by natural processes.

Cities are complex, highly organised structures made up of countless unpredictable individuals, each with a personal agenda made up of needs and wants, informed by circumstance and whatever knowledge each possesses, yet collectively, people are predictable. Can anarchists make cities? Surely, cities require leadership? Street Farm provided a kind of leadership, demonstrating the ethos that leaders should offer concrete solutions to real problems and proffer working models of what can be achieved, but should not lay claim to membership of any kind of pantheon. In this model of leadership, skills, ideas and organisation are made available for as long as they are needed without dynastic tendencies or attempts to cement the leaders themselves into a permanent power structure.

Mikhail Bakunin, founder of ‘social anarchism,’ is famous for claiming that ‘the urge to destroy is a creative urge.’ That can be understood as another way of saying we’ve got to get rid of dead wood. A number of people would argue that on a planet where the very survival of our species is threatened by anthropogenic climate change, the urge to destroy the hegemony of coal and oil companies is an entirely creative urge. Even then, that process of destruction demands that people work collectively to achieve it; they cannot be in constant opposition to one another. Street Farm’s creative urge offered images of destroyed cities, but these were existing cities transmogrified—a favourite Street Farm term—from lifeless piles of concrete into places reinvigorated by nature, covered with vegetation and, crucially, under the direct control of their citizens.

Advocates of green cities and ecological urbanism might wonder where their ideas come from or not care at all. But I hope they will understand that if they are to succeed in shifting the culture, a memory helps. Henry Ford may have claimed that ‘History is bunk,’ but for a culture to lose its sense of history is like a person losing his or her memory. The person might still function at a basic level, but loses nuances, sense of meaning, purpose…and, most of all, can’t learn from past mistakes or successes. When Street Farm advocated alternative (renewable) energy, they drew from Bookchin and made the crucial distinction that they were proposing the use of liberatory technology… ‘a technology that will change the existing situation,’ whereas ‘alternative technology is one that will make the existing situation more tolerable.’

In many ways, it is possible to discern Street Farmer sensitivities in much of the best of modern practice and theory in regard to urban systems. Hunt argues that their revolutionary view of the nature of cities was an expression of ‘an ecological sensitivity that aspires to human interaction with the natural environment and other species and looks to confront and abolish the urban/rural divide.’

Street Farm paved the way for an approach to urbanism that is simultaneously playful and trenchantly critical, whilst putting forward ideas about what cities should be like that encompass social justice and revolutionary change, and ceding a central place to the fecundity of nature and the energy of community. That’s no small vision, especially considering that they were active at a time when environmentalism was pessimistic to the point of being ‘doomful’—which was a reasonable response to the increasingly informed analysis, exemplified by Limits to Growth, which warned of ecological and thence social collapse without major shifts in the patterns of industrial civilisation. That those warnings were not heeded is an historical fact, that the general gist of the warnings was correct is disputed with the same fervour that some apply to denying that the Nazis designed and manufactured the Holocaust. Hunt rightly points out that Street Farm were not ‘doomful.’ Their critiques and analysis of the dominant paradigms of capitalism and its consequences in the creation of modern cities wasn’t cheerful—how could it be?—but their solutions were marvelously creative, positive and joyful to anyone who could see past conventional prejudices.

Hunt concludes with a chapter that includes the offer of ‘an index of possibilities’ for how a revolutionary urbanism might be realised. This is an entirely legitimate exercise but it interrupts the flow of his otherwise immensely readable narrative by being in the form of a slightly clunky, annotated list of nineteen items like ‘Ecological awareness’ and ‘Thoughts to street furniture’ that could have been presented better in an appendix. The rest of his concluding chapter would have read well without this in its middle, and perhaps could have avoided the question of whether a list that included the ‘Rational organisation of space’ had quite the Situationist timbre that the topic deserves and that, otherwise, the book conveys well.

This book will be of particular interest to anyone with an interest in the lineage of ideas that have informed the movements towards ecological design, eco-architecture and green cities. Those with an interest in radical politics will find it a comprehensive and very digestible study of one of the ‘lost treasures’ of the counter-culture. This thoughtfully illustrated book may favourably dispose the reader towards the concept of transmogrification and it should be read by anyone interested in efforts to refresh, remake or reimagine the nature of our cities.

Paul Downton

Adelaide

About the Writer:

Paul Downton

Writer, architect, urban evolutionary, founding convener of Urban Ecology Australia and a recognised ‘ecocity pioneer’. Paul has championed ecological cities for years but has become disenchanted with how such a beautiful concept can be perverted and misinterpreted – ‘Neom' anyone? Paul is nevertheless working on an artistic/publishing project with the working title ‘The Wild Cities’ coming soon to a crowd-funding site near you!

Add a Comment

Join our conversation