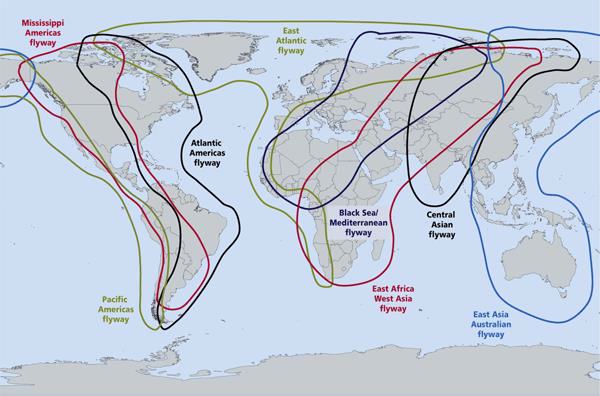

In our transition from rural to urban life (arguably the largest ever migration of humans on Earth), we lose contact with Nature—that we already knew. It is not easy to find ways to raise awareness of the beauty, as well as the critical role, that living beings, all 30 million species of them, play in giving us our health, food, air and water in our cities. One interesting approach I’d like to propose here is to appropriately manage the natural attraction we have for birds and other animals (from butterflies to whales to bats), notably those migrating “en masse” across continents and seas looking for food or protection in wetlands or protected areas. Not surprisingly (as birds are evenly spread across all biomes in the world, and as around 1,800 species of migrating birds represent about 19% of known bird species), so-called “bird flyways” cross all continents and ecosystems.

Birds are colorful, visible and ubiquitous. Three million people take international trips each year to witness the spectacular movements of migratory birds, traveling thousands of miles along their flyways, but it is estimated that domestic numbers can easily attain 10 times more. According to US Fish and Wildlife Service, bird watching is reported as being the fastest growing outdoor activity in America with 51.3 million people contributing more than $36 billion to the US economy in a year. In the UK, expenditure is estimated at $500 million each year and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in the UK has membership of over 1 million people. It is thus not a surprise that the Mexican birdwatcher and architect Hector Ceballos-Lascurain coined the term “ecotourism” in 1985 working in an American Flamingo breeding place in northern Yucatan.

“Birding plays a significant and growing part in the tourism industry, and creates direct and indirect economic benefits for many countries and communities, also amongst developing countries. Wildlife watching appeals to a wide range of people, and opportunities to participate in wildlife watching are and should increasingly be a factor in tourists’ holiday choices today” said Elizabeth Mrema, Acting Executive Secretary of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).

Like tourism in general, that attraction to migrating birds can be compared to fire in terms of its relation to the protection of Nature: it can cook your food but can also burn your house down. The right kind of “bird flyway” tourism can help finance parks for these migratory animals, can raise political attention and public awareness to these often endangered species, and can provide much-needed and relatively low-impact jobs and business opportunities for local communities around parks, making them allies for biodiversity (and for the implementation of multilateral agreements like the Convention on Biological Diversity, for which we work). Without the right institutional governance setup, however, too many people can literally “love the parks—and the birds—to death”, or what is as bad, unvisited and badly managed parks of critical importance to the birds may be left to waste outside of the public view and we lose the opportunity to put birds and parks towards decent livelihood options and source of pride for locals. Those areas (most often wetlands and watersheds) also provide surrounding communities with freshwater (wetlands are very cost-effective filters—treating water chemically and through water plants costs around 10 times more) and leisure options (strongly linked to urban health).

Moreover, it turns out that in terms of governance, success or failure of these initiatives depend largely on the close cooperation between national, subnational and local governments mediating and facilitating cooperation with business, civil society and other major groups. The sustainable use of such “bird flyways” as tourism attractions depends largely on the capacity of local and subnational governments to conserve their biodiversity and ecosystem functions, restore degraded areas and leverage the business opportunities from tourism for residents and park agencies alike, always involving civil society in governance and stewardship.

Some examples of migratory animals as tourist attractions

- Ann W. Richards Congress Avenue Bridge, Austin, Texas, U.S., is home to the world’s largest urban bat colony. The Mexican free-tailed bats reside beneath the road deck in gaps between the concrete component structures. They spend their summers in Austin and migrate to Mexico in winters. According to Bat Conservation International (BCI), 750,000 ~ 1.5 million bats come and nest in the bridge each summer. The nightly emergence of the bats from underneath the bridge at dusk, and their flight across Lady Bird Lake to the east to feed themselves, attracts as many as 100,000 tourists annually, with economic impacts on the city reaching US$10 million each year. A project called “Bats and Bridges” has been put in place by the Texas Department of Transportation, in cooperation with BCI, to study the best way to make bridges habitable for bats. The Austin Ice Bats minor-league hockey team was named in honor of the bats.

- Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve in Singapore was designated as a nature park by the government in 1989 and officially opened to public in 1993, and has received constant support to help preserve its beautiful space and its vast variety of nature and wildlife. The reserve was recognized as a site of international importance for migratory birds with Wetlands International presenting the reserve a certificate to mark its formal entry into the East Asian Australasian Shorebird Site Network, which include Australia’s Kakadu National Park, China’s Mai Po and Japan’s Yatsu Tidal Flats. From late 1990s to early 2000s, it received 80,000 – 90,000 visitors annually on average, of which 4,000 were tourists. Now as one of leading wetlands in the flyway, it has currently over 130,000 visitors and the number has been increasing every year as the site becomes better known and its reputation for conservation and awareness-raising is increasingly appreciated.

Taking action at UN level

Building on these and other examples, key partners with experience in the field of conservation and tourism have joined forces to design a Flyways and Sustainable Tourism project. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the Secretariat of the Convention on Migratory Species (UNEP/CMS, which in 2006 produced a seminal publication on the topic), Wetlands International and Birdlife International (as implementing partners) are collaborating with the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD), UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (UNESCO/MAB) and World Heritage Centre (UNESCO/WHC) Programmes, the Ramsar Convention Secretariat, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to protect migratory birds and their habitats and support the creation of sustainable livelihoods for local communities through the development of innovative sustainable tourism products. In the first phase, the Flyways and Sustainable Tourism project focuses on the East Atlantic, West Asian East African, Central Asian and East Asian Australasian Flyways.

Since 2006, negotiations to implement several multilateral environmental agreements (the Convention on Biological Diversity but also the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the Convention on Migratory Species, the World Heritage Convention and the selection of Important Bird Areas), have advanced on the critical role of local and subnational authorities, supported by national/federal governments, in ensuring that wetlands are well used BOTH as freshwater security “insurance” and as tourism attractions—with economic benefits reverting both to steward communities and to the park agencies responsible for monitoring and minimizing impacts of visitation. While federal governments are expected to provide guidelines, incentives and policies that create the enabling environment for those solutions, as well as leverage the use of national parks, subnational governments can apply appropriate land-use planning tools, leverage their parks and provide appropriate infrastructure. Local authorities, in their turn, can enforce rules, apply incentives and help incubate key businesses, involve and educate citizens, manage and restore ecosystems.

The critical role of local and subnational authorities

The sustainable management of tourism equipment and facilities for visitors, including the freshwater security aspect of wetland protection and restoration, depends largely on the capacity of local and State/regional/provincial (i.e. subnational) governments. Protecting water sources and the ecosystem service of filtration is critical to the quality of life of local residents, but often even more so for tourism: freshwater is one of tourism’s key resources (international tourists easily consume 10 times more water than local residents according to a study by Conservation International and UNEP) and a crucial resource in the years to come (between 1980 and 2000 available per capita freshwater supply decreased by almost half).

An interesting example comes from South Korea (the CBD COP 12 host in 2014), where Seocheon County in Chung-cheong-nam Province is being considered as one of the 8 sites of the UNWTO project. The Secretariat of East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership is also housed in Incheon. Suncheon-si is a small city located on the southern coast of South Korea, once left behind in the country’s industrialization race. A debate on Suncheon Bay’s restoration started in the late 1990s, as the administration decided to follow a different growth path. While surrounding areas devoted wetlands to industrial purposes (mostly petro-chemical plants and steel mills), Suncheon-si launched a project to restore the tidal flats into the largest sanctuary for hooded cranes.

As a result of concerted efforts by the city government and its citizens, Suncheon Bay was designated as one of the first coastal Wetland Protection Areas in 2003, and South Korea’s Ministry of Environment applied its experience with river restoration in Jeonju, Suwon and Cheonggye streams. Suncheon Bay was designated as the first Korean coastal wetland registered on the Ramsar list in 2006, and is now one of the top ecotourism destinations in the country. Additional investment in complementary infrastructure facilitated the arrival of more than 2.95 million visitors in 2010, a dramatic increase from the 0.1 million tourists in 2002. By the end of 2009, about 6,400 jobs had been created in a city of just over 200,000 people, and more than US$87 million was generated only in 2010.

One interesting fact is that the number of wintering birds in the bay also has increased, in a clear conservation/development win-win model. Nineteen species with 5,210 individuals of migratory birds were found in 1999, and with enhanced governance these totals reached 125 species and 58,000 individuals in 2011. The number of Hooded Cranes, the flagship species, was only 60 in 1996 but now is 660 in 2013.

Source: Suncheon Bay Garden Expo

Source: Suncheon city and Ramsar

Suncheon’s key success factor lies mainly on the local government’s strong leadership supported by the national government’s policies. Initially, plans to restore the Suncheon Bay ecosystem met strong resistance from business and land owners whose private interests were restricted when commercial areas were relocated out of the bay area, and rice fields were turned into a reserve for migratory birds. Strong leadership by mayors was the critical factor in turning initial resistance into support and eventually into political success.

- The collaborative relationship between civil society and the local government was formalized in 2007 when a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the Korean Federation for Environmental Movement (Korean NGO) and the Suncheon city government promising continued cooperation for ‘the efficient conservation and sustainable use of Suncheon Bay’.

- At the local level, the Committee on the Ecology of Suncheon Bay, consisting of 30 local residents, experts, and NGO members, has been organized to collect opinions, provide policy advice, and establish a cooperative system among various stakeholders.

The importance of national, subnational and local government’s collaborative and complementary roles can also be seen in New York City’s very recent plan of restoring Jamaica Bay. In 2010, U.S. President Obama launched the America’s Great Outdoors Initiative as an agenda for conservation and recreation in the 21st century, proposing that the federal government partner with States and local communities to rework inefficient policies and establish conservation solutions. As part of this effort, the U.S. Department of the Interior, the National Park Service, and the City of New York met with other public agencies, non-profit organizations, and private groups to seek new opportunities for collaboration. Last May 2013, NYC Parks, in partnership with the National Park Service, launched the Jamaica Bay/Rockaway Parks Restoration Corps, with funds from a National Emergency Grant through the U.S. and NYS Departments of Labor. Approximately 200 workers were hired to assist in the clean-up, restoration, and reconstruction of Jamaica Bay and Rockaway Parks – including areas that sustained serious damage from Hurricane Sandy.

Nitrogen discharges were significantly reduced, waterfronts restored, existing natural areas were recovered based on science, and the actions and financial investments of federal, state and local agencies were coordinated with environmental stakeholder groups. Sustainable urban infrastructure (more permeable, with better drainage and was developed as part of NY’s Green Infrastructure Plan. Seaweed was converted into biofuels, oyster beds were recovered and endemic plants reintroduced. Improved satellite environmental monitoring allowed for the production of the Jamaica Bay Watershed Ecological Atlas. Enhanced attractiveness of the area led to visitation almost doubling between 1994 and 2008 (4 to 9 million visitors/year).

Conclusion

This brings us back to the UNWTO project. One key issue on which the Secretariat of the CBD would like to cooperate with all partners, most specially networks of local and subnational authorities, is to focus on capacity-building processes for these levels of government to promote sustainable tourism development as an effective and sustainable mechanism for job creation and regional economic development, always linked to successful conservation and management of wetlands and protected areas in the Migratory Birds Flyways as critical biodiversity and tourism hotspots. Please contact us at [email protected] for more information and exchanges.

Oliver Hillel

Montreal

with Jiyong Huh, SCBD intern and Seoul University Business School graduate

Leave a Reply