Understanding the nature of the place in which a city exists must be a priority, and involves sensible use of the local context, building in a manner consistent with the particularities of topography—an imperative highlighted in the Colombian Andes—and appropriate integration with hydrology and water flow systems, biodiversity, and other ecosystem characteristics.

Although it is less conspicuous than vegetation in dense urbanized areas, water, the source of all life, is just as vital.

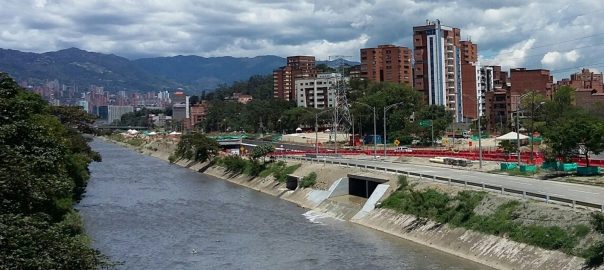

Medellín is the second Colombian city, located in the center of the Aburrá Valley. It is also the main settlement of the 10 municipalities that comprise the denominated Metropolitan Area of the same valley. Medellín has not been an exception to the modality of enforced, rigid, uncontrolled urban occupation over the wrinkled topography of wild or rural areas in Colombia. The colonial introduction of the damero pattern over topological and hydrological conditions, which suggests and even demands other responses, has been repeated across the whole nation’s urban setting. Many disastrous events, such as landslides and annually repeated floods, have demonstrated that we need a harmonious dialog of design and nature.

Despite Medellín’s successes (e.g., in transportation and social urbanism), we haven’t done so well in our relations with nature. Public authorities and people in general feel that the duty towards nature is fulfilled by projecting numbers of trees to be planted, when possible.

Although it is less conspicuous than vegetation in dense urbanized areas, water, the source of all life, is just as vital. Discreet most of the time, but forceful when it occurs in a large body or when it appears suddenly (especially in respondse to climate variations, which have lately become unpredictable), water reacts by following clear hydrological laws and according to the way urbanization, unaware of its effects, has modified the relief and corresponding bed, surfaces, and spaces for free and natural flow.

In particular, cases such as Stuttgart, Boston, St. Petersburg, Zurich, Delft, and Woodlands, Texas, are quite illustrative of a sound dialogue with their water bodies. These cities have become well known for their understanding and harmonious coordination with the aquatic realities of their specific locations. In Colombia, one of the water-richest countries in the world, there is a long way to go in the realms of knowledge and acceptance of the behavior of water in urban settings. In urban planning processes in Colombia, people’s primary concern has tended to be determining the quickest way to get rid of water as soon as it reaches urbanized surfaces. The conviction that we have an abundance of water is counterproductive and reduces our impulse to care for and retain sensible interactions with the hydrological cycle.

The mistreatment of watercourses has been increasing since the first half of the 20th century, when urban planners with narrow, purely utilitarian aims sought to “sanitize”, urbanize, industrialize, and transport. At that time, the administrative authorities decided to “rectify” and channelize the river Aburrá, axis of the valley and source of life in many senses.

Upstream, this “rectification”, channeling, and continuous urban growth mounted along the valley slopes at the fringe of each and every one of the tributary streams, until, today, no brook crossing through urban areas in Medellín leads its waters naturally towards the river. Most of the streams across the city have at least part of their routes channeled in concrete, when they are not fully encased. Images of channels, walls, pipes, and concrete beds have become so familiar that people do not remember the original names of the watercourses, and indistinctly refer to all of them as “the channeling”.

The rapid and little-controlled urban advance towards the mountains’ edges led planning authorities to an idea: draw a thick line to stop the city’s sprawling tendencies. This is the origin of the so-called Metropolitan Green Belt (from the metropolitan administration) and Encircle Garden of Medellín (from the municipal administration). Though the main—and quite optimistic—purpose of that line was to stop urbanization, the names suggest a concern for nature that has not materialized. Although these works, already accomplished, include a certain amount of vegetation, they are dominated by cement or brick tiles, hardening the bed of small runoffs instead of transforming it, as a true green belt would. Certainly, effort has been invested in good quality works, which have been well received by the community. Directors of these projects have involved the suburban communities, and the results have stimulated the recognition of previously inaccessible places and the need to work on increasing biomass. But the water has definitely been the forgotten main actor of the story.

A similar situation occurs again halfway between the mountain ridge and the mouths of creeks in the river, through the scarce green open spaces within the urbanized areas. Even when spaces are converted into parks, in these green patches, water is mistreated. This is the case in the Gabriel Garcia Marquez Channel Park, where a nice recent opportunity to interact with running water in a respectful way or contemplate it, as a constituent part of the landscape, has been wasted. On a plot that used to be the municipal nursery, the sport television offices established themselves, accompanied by a park. Although some of the works respect the natural spirit of the place, in affluent areas, the existing water and vegetation were displaced by rigidly disposed water channels and plants.

We urgently need to attend to water in all its manifestations. All levels of society have responsibility in this task; it must be faced via a joining of wills from several society groups: authorities, administration, the academy, communities, developers, schools, etc.

As it has progressed, studies and guidelines to improve the quality of urban development have been published. The most recent for the Area Metropolitana del Valle de Aburrá is 2015’s Política Pública de Construcción Sostenible (Sustainable construction Public Policy). This policy, which integrates natural resources and building construction, is addressed to builders and developers and articulates the inextricability of principles of biodiversity and environment with gray infrastructure and engineered solutions. The work consists of eight books and, although its overarching title could be interpreted as being focused on buildings, it involves elements from wider scales. If we accept, as the above policy states, that “a collection of sustainable buildings does not produce a sustainable city”, the traditional scope of sustainable building must widen to encompass the open space in between buildings.

The policy´s first book, called “Base line,” orients the reader to a detailed analysis of the place before intervening in it. The book covers all aspects of the landscape, such as ecosystems, biodiversity, natural landscapes, water, and green spaces. In this sense, the document suggests that the recognition of any water flow is important for understanding it and using it in a sound way. Such recognition also raises awareness of the threats from flooding and torrential overflows.

The purpose of this book is to stimulate a responsible attitude towards natural water functioning and avoiding interference caused by unconscious works in open space. Although there are examples and references in many countries, this is the first time that these principles are clearly and explicitly “translated” to our own environment, to be adopted by normative force, for a much more stimulating habitat.

The first step would be to spread the existence of these tools, followed by studying and digesting them, before applying the experiences that emerge from them in every new urban intervention by demanding responsible agents to implement them.

As Gary Grant says in his recent article, “Towards the Water-Sensitive City” (TNOC June 2016): ”When city authorities begin to consider the fabric of the city itself as a rainwater collection facility, this changes the way people design and operate the urban landscape.”

We won’t be able to complain after flooding disasters occur in the lower parts of our cities if, together, we all do not drive attention and efforts to understanding nature’s flows or articulate development interventions to these problems through overly simple adaptation strategies.

Nevertheless, Medellín has recently received international recognition because of its strong and continuous work to reemerge from a pronounced social decline that the city experienced at the end of the last century. Due to its persistent efforts in terms of coexistence, civic culture, equity in public services, and transport systems, Medellín can now share certain important achievements. The unwavering work of various bodies and successive administrations earned Medellín the following awards:

- Medellín won the title of most innovative city in 2013, competing with the cities of New York and Tel Aviv for the “City of the Year”, organized by the Wall Street Journal and the Urban Land Institute -ULI-

- Medellín won The MobiPrice 2015 prize for its model Metro System and EnCicla program, each of which is unique in Colombia

- Medellín won The Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize for their sustainable and innovative urban approach in March 2016

Medellín has thus become a national and international example of social inclusion and the organization of urban operations. However, this does not mean that the city has solved all problems related to everyday urban life. A great debt is still latent: attention to the city’s relationships with its natural ecosystem, particularly water, and equilibrium between urban activity and the city’s “metabolic capacity”— goals of actual “sustainability” that must go beyond semantics.

Our debt is mainly to the abundant water that runs towards the valley axis, which urban development works strive to hide. We all have to remember that water is also nature!

Gloria Aponte

Medellín

Leave a Reply