Different schools of professional and academic thought have recently emerged to address the unprecedented problems of the sprawling megacity. One particular group believes that solutions will emerge from the cultivation of data and vast amounts of statistical research. This activity, which is sometimes referred to a “datascaping”, reduces the complex problems of megacities to verbal logic that has the capacity to inform other verbal systems, such as the regulatory statutes, zoning, by-laws, comprehensive plans, and public policy of a city.

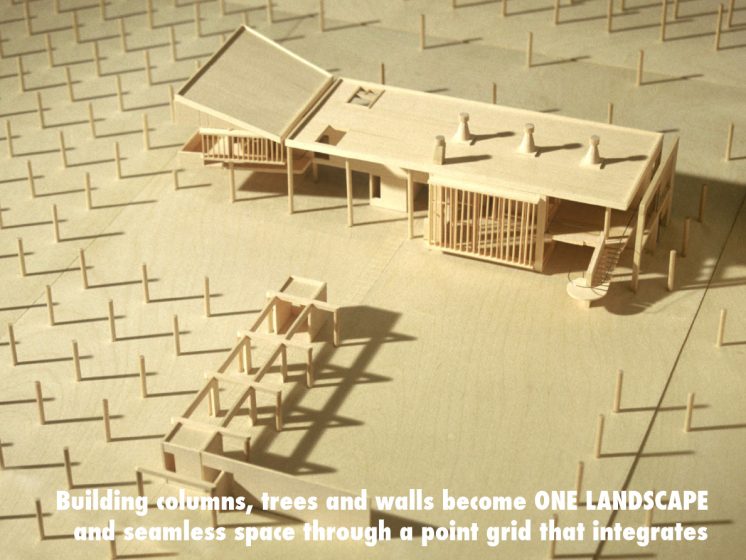

The suburban megacity feathers through endless gradations, from city patterns and built systems to nature and bio-morphic systems, forming ONE LANDSCAPE.

Another group, comprising architects, landscape architects, and urban planners, see the megacity as a design problem. Born out of a long and time-honored history of urban design, this notion extends from a conviction that the spatial arrangements of a city and the uses they contain can be designed, altered, or permuted to foster the social and economic relationships of a society and its goals. In contrast to the datascapers, this group largely sees the city as visual and spatial logic—in other words, Architecture.

Rather than debate the legitimacy of which one is right or better, that a unified theory and nomenclature of megacities do not yet to exist is perhaps a clue that they are not yet accurately understood or characterized. For example, to refer to Rome as a “city” and Los Angeles as a megacity implies that LA is simply a gigantic version of the Roman pattern, which, of course, it isn’t.

Perhaps a productive step would be to characterize the megacity more accurately by its attributes rather than by using nomenclature that is inaccurate or insufficient.

ONE LANDSCAPE

Pulitzer Prize winning architectural critic, Robert Campbell, offers a useful potential assessment of the megacity and its relationship with nature in “Still Steel” for Landscape Architecture Magazine.

“For the first time in human history, the entire world both built and un-built is being considered as one continuous landscape. It is a profound way of re-conceiving architecture (landscape) and cities.”

This article will explore and discuss the suburban megacity and/or mega-region as a landscape that feathers through endless gradations of city patterns and built systems on the one hand, to nature and bio-morphic systems on the other—i.e., ONE LANDSCAPE.

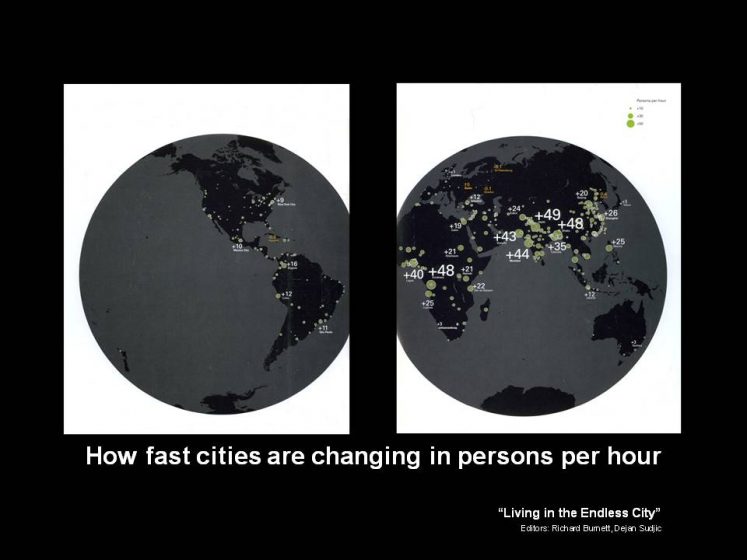

The article begins with a diagnostic of the suburban megacity that maps out a supportive framework for the notion of One Landscape. Density analyses of various cities and urban geographies will be used to reveal pattern characteristics.

Two potential techniques that can intervene in landscape-like patterns follow the diagnostic. The first is based on the notion of “reciprocity between buildings and landscape”, a conceptual device that was loosely utilized by planners and designers in the mid- to late- 20th century. The second is a particular kind of drawing technique that exploits the formal vagueness of megacities and the potential to introduce new qualities within them that unify urban design, landscape, and ecological impulses.

WHICH DENSITY OFFERS HOPE?

Experts on urbanism extol “density”—the ratio of humans to an area of measurement—as an attribute that “offers hope for the future” as a potential strategy that can restructure a suburban pattern. However, simple questions quickly arise. For example, what is the density goal? At what density does urbanity ignite—i.e., what is a target density? And then, by logical extension, would the same density that produces a social and economic network also be sufficient to make energy consumption efficient and economical? Or are these different density thresholds?

And, conversely, at what concentration of building forms and density is the potential for nature and ecologies to exist within a city driven out and replaced by an entirely constructed environment? Simply put, does “density” mean Hong Kong, or is the density of Boulder, Colorado or Savannah, Georgia sufficient, and for what?

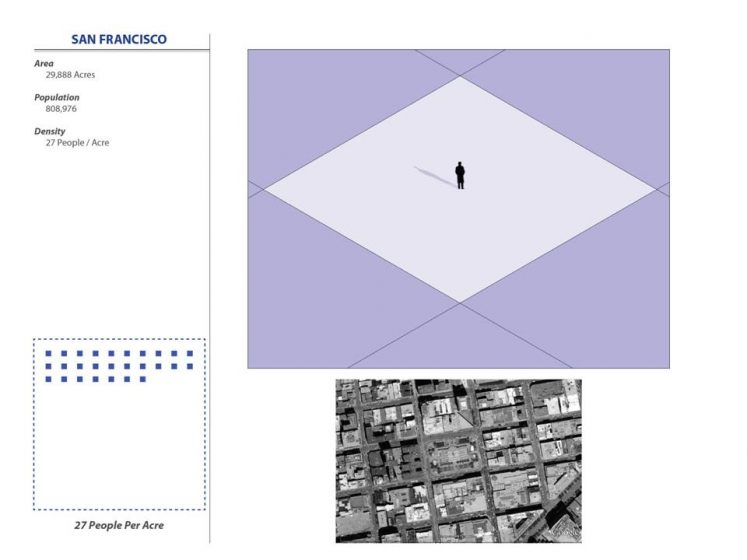

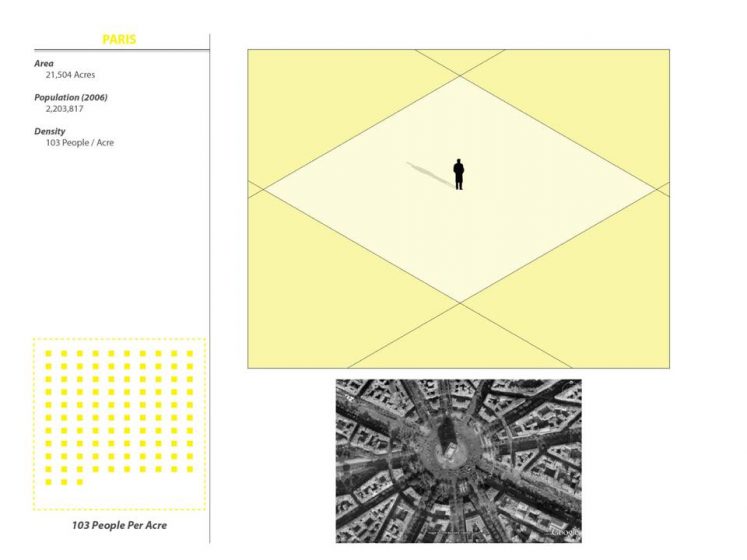

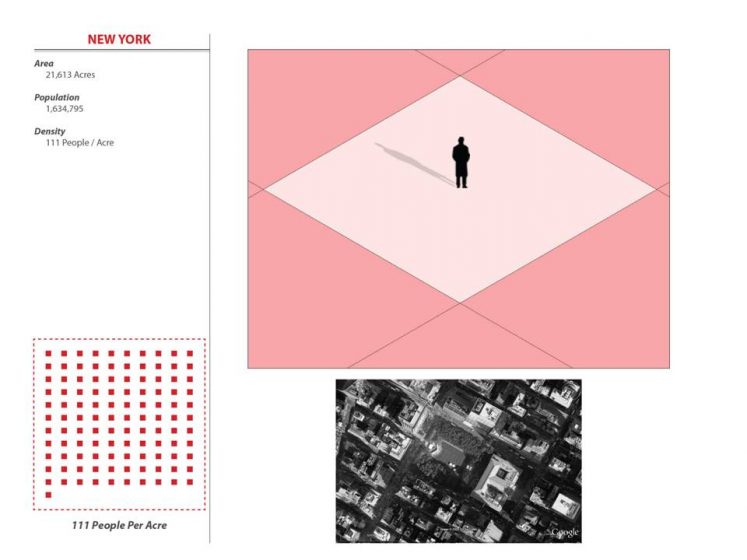

An inventory of the density of key world cities is revealing. The density comparisons that follow take into account only the residential population of a city or region and the area it encompasses. For purposes of this analysis, this limitation avoids potential density distortions that are created by surging commuter populations that originate from outside a geography, and which can heighten the urban performance of an area with pulse concentrations.

When considering only its residential population, San Francisco’s density is 27 people to an acre. Given that San Francisco is generally seen as a highly urbane world city, its surprisingly low resident-density, which stabilizes the urban performance of the city, is also evidence of the commuter surge delivered by BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) into the financial and governmental quarters of San Francisco.

The resident-density of Paris is 103 people per acre. At over four times the resident-density of San Francisco, what comes quickly into focus by comparing the two cities is that Paris is an extraordinarily efficient urban pattern, with an abundance of avenues and public spaces. We can infer that it isn’t as reliant on a commuter surge and/or that the weaving of residences with shops and small officing must be exceptionally integrated and fine-grained to sustain a resident-density of over 100 people per acre.

The resident-density of New York City is even higher than Paris at 111 people per acre. According to Professor Kenneth Frampton, the daily commuter surge into Manhattan can drive the resident-density even higher, with guesstimates falling somewhere between 500 and 1000 people per acre.

Comparing the density of these world cities—which originated around a historical core or a colonial center, or were hyper-densified by unusual geographical restrictions such as those posed by Manhattan island—with the 20th-century suburban megacities of the North American Sunbelt reveals a shocking if not an alarming, reality.

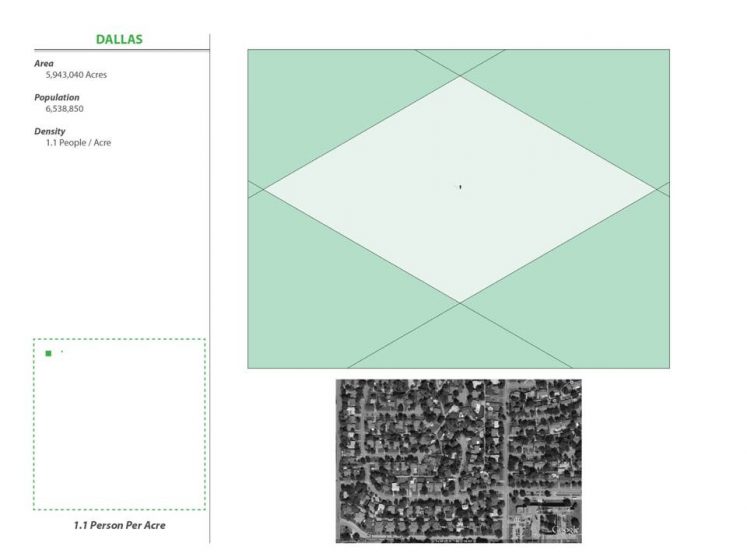

The average human density of Dallas-Fort Worth (or DFW) is 1 person per acre. Unaffected during its rapid expansion by any natural boundaries that might interfere and generate density, what has materialized in DFW instead is a pattern that undergoes a machine migration every day: residents abandon vast tracts of purely residential geographies to commute to purely “officing” or shopping geographies. Taken together with the public easements established for intercity highway and infrastructure, multiple airports (including the colossal DFW International Airport), and its system of water-harvesting reservoirs, every person living in DFW currently requires one acre of civilization to exist.

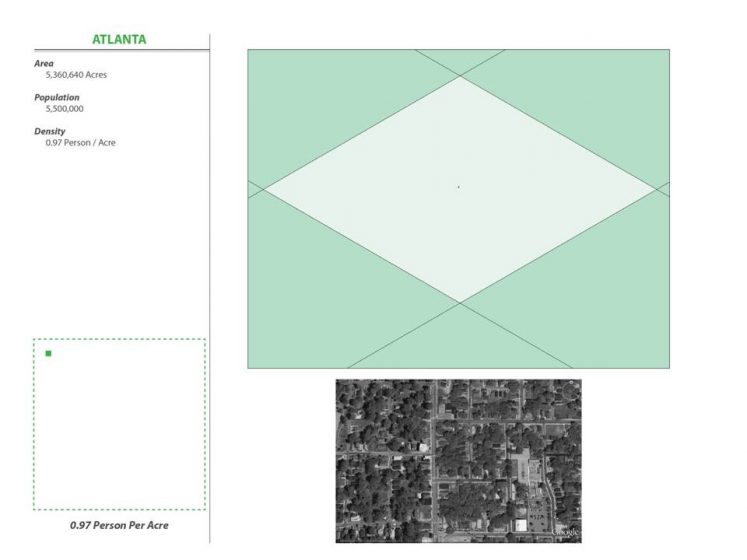

While the astonishment of such a land and resource consumption pattern settles in, keep in mind that Atlanta is virtually the same, with 0.97 persons per acre. Indeed, the same analysis applied to virtually all Sunbelt cities—Houston, Austin, Las Vegas, and others—yields a resident-density of approximately one person per acre.. Since all these cities were largely constructed with the same kind of engineered pattern—designed to the same parameters of traffic, safety, and turning radii—they essentially are one in the same place. Little wonder when critics and writers wax about the “lack of place” that typifies these kind “Generica” environments, they are stating facts that can be supported quantitatively. Whether it was offered as a critique or simply a statistical fact, architect Rem Koolhaas, during his 2008 lecture for the opening of the Wylie Multi-form Theater in the Dallas Arts District, called Dallas (DFW) the, “Epicenter of the generic.”

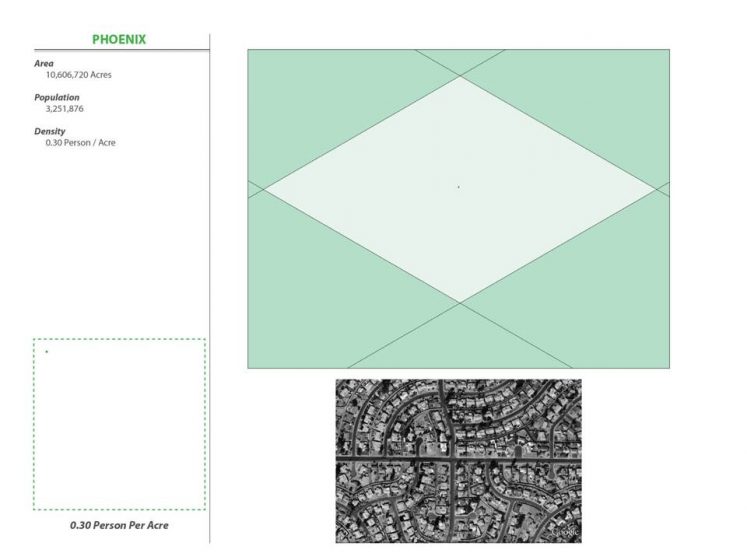

Only Phoenix, with 0.30 humans per acre—essentially one third the density of all the others—distinguishes itself from the monotonous hyper-pattern of the North American suburban megacity, which has produced one landscape built at an average resident-density of one person per acre.

ONE LANDSCAPE AT ONE PERSON PER ACRE

By comparison with hyper-dense cities, the strikingly thin density of the suburban megacity raises a broad spectrum of questions and potential speculations. It provides evidence for why attempts to create nodes of urban concentration and density struggle to succeed. Urban formations are inherently more complex and expensive to design and construct. Costs to achieve them are transferred into the lease and purchasing rates for officing, retail, condos, and apartments. The spike in price point is theoretically offset by the advantages offered by urbanism that include culture, convenience, walkability, safety, and a generally vibrant and satisfying urban environment.

What can be observed with almost documentary evidence is how the thinly densified suburban area around a dense node tends to exert a dissipating effect on the benefit of urbanization by diffusing the amenities of concentrated land uses: cheaper rents and real estate are supported by an endless array of alternative land uses that are equally accessible by motorcar.

The cause and effect relationship between density and urbanity may be more complicated than the simple notion that attaining higher and higher densities should always be the objective. For example, several U.S. cities, such as Portland, Oregon; Madison, Wisconsin; Boulder, Colorado; and Savannah Georgia frequently top rankings of urban places that are highly desirable to live in. The same density analysis approach in these cities reveals the following:

However, it is the counterintuitiveness of the analysis that brings into focus a more poignant revelation about the suburban megacity that may be its most urgent and irreversible characteristic.

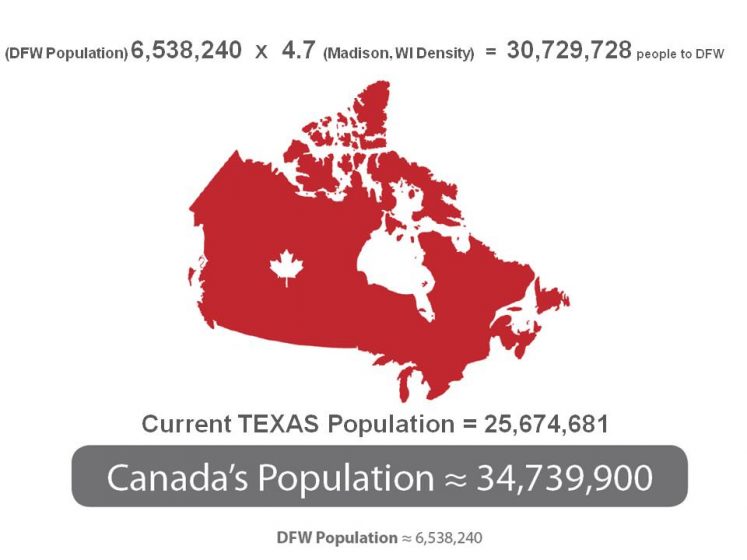

Using North Texas as a typical case study region, we see that 11 separate counties comprise DFW and they incorporate approximately 7 million acres of civilization for approximately 7 million residents. As a simple thought experiment, consider what would happen if the entire DFW metropolis attempted to universally densify to equal the charming and town-like density of Madison, Wisconsin, with 4.7 people per acre. Simple arithmetic reveals that the entire population of Canada would have to move to DFW to inhabit the new and denser city of 36 million people.

Does this potentially mean that any attempt to urbanize the suburban megacity is fundamentally doomed, an exercise in futility or romance for a town-like history that cannot be achieved? Has the unbridled growth and horizontal expansion of the North American city made the suburban megacity statistically impossible to retro-densify? Obviously, nodes of concentration can exist within the pattern, but even the most modest density objectives of, say, a Savannah Georgia-like density project, quickly produce a statistical reality that cannot be achieved. Even if the denser formations were built, there simply wouldn’t be enough people to occupy the buildings.

This documentary evidence could lead us to conclude that the future will, in fact, be One Landscape where nature, either cultivated or “wild,” co-exists with diffuse patterns of civilization that feather across density and nature layers. To meaningfully design new places, design strategies that interchangeably consider nature as architecture and buildings as site elements are needed. A strategy that considered such a hypothesis throughout the history of cities and gardens, as well as in the modern age, that could be useful to the contemporary problem of the suburban megacity, is known as “Reciprocity.”

RECIPROCITY IN HISTORY, LANDSCAPE, ARCHITECTURE & ECOLOGICAL DESIGN

Webster’s definition of reciprocity is “a situation or relationship in which ‘two people or groups’ agree to ‘do something similar’ for each other.” When reciprocity is applied as a design tool for architecture and planning, the phrase “something similar,” means the definition of spaces and places of most types and at most scales for human use. In extending the metaphor and application of reciprocity to urban planning and landscape design, the preceding phrase, “two groups,” that Webster mentions, can refer to architectural elements such as columns, walls, volumes and planes that can “reciprocate” by design with biomorphic and/or landscape elements such as trees, hedges, bosques, and orchards.

The key to reciprocity is that the mutual design of buildings and landscape elements should be a perceivable characteristic to individuals who inhabit environments or spaces that have been reciprocally conceived. Reciprocity is the result of deliberate and composed relationships that put buildings and landscapes into the “reciprocal” role of defining, mending, correcting, making a space or place that is a shared objective. The product of reciprocity is a continuous landscape where buildings and nature are spatially woven into a seamless fabric.

A simple and basic example of reciprocity between buildings and landscape, can be observed in how two repetitive lines of dots can signify the columns of a trellis or colonnade, or the trees of an alley or tree-lined path. If two such conditions were combined, the cadence of the trellis columns could continue into the cadence of the tree trunks and vice-versa.

The same thinking would apply to how a thickened line, drawn in plan view, can signify a building or landscape wall and/or a plant hedge. By further logical extension, a rectangle or volume in plan view, can signify a building footprint—a house—or it could signify a Bosque of trees, or even a biofilter that is planted and filled with dense underbrush.

These basic examples demonstrate how reciprocity can produce environments that are accomplished with the spatial integration of built and biomorphic materials of landscape. Creative extrapolations can rapidly multiply from the basic examples, into a playful and disciplined activity that is rich in possibilities, and thus “The game,” as Shakespeare wrote, “is afoot.”

Traces and built incidents of reciprocity occur throughout history as well as in contemporary buildings and landscapes. While reciprocity has existed as an infrequent occasion for making architecture, gardens, and cities, it could be used more often as a tool to make places and spaces in the diffuse pattern of the suburban megacity.

Two case studies follow that are intended to explain and highlight how reciprocity existed in the Renaissance garden of the Villa Gamberaia, as well as in The Nasher Sculpture Center, a 21st century accomplishment by architect Renzo Piano and landscape architect, Peter Walker FASLA.

Reciprocity in History: The Villa Gamberaia, Settignano Italy

Situated on a Tuscan ridge near Settignano, Italy, and in the hills above Florence, the Renaissance Villa Gamberaia is a textbook demonstration of how garden spaces can be reciprocally conceived with building and landscape elements. Along with the shifted formal relationships of buildings and plant materials, meanings and perceptions produced by the reciprocal operations also shift, adding richness that is an inspiration for how conceptual and perceptual intentions can co-exist in a place of unprecedented beauty and delight.

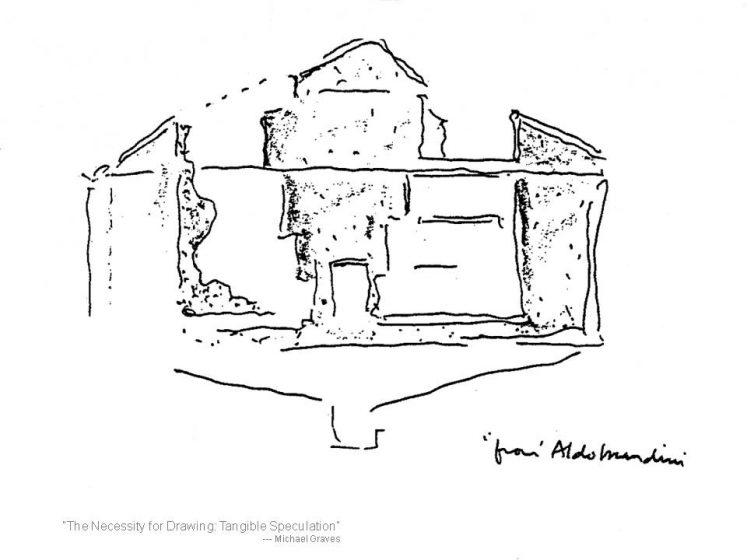

In the same way that the overture of an opera proclaims the essential themes of the musical production, the arrival sequence at the Villa Gamberaia announces to the observer that the entire garden will unfold as an interplay between landscape elements that are rendered as building elements, and building elements that are realized with landscape materials.

The foreshadowing role of the arrival sequence begins on the country road that extends a short distance from the town center in Settignano to the villa entrance, and proceeds through a concavely shaped gate and into a narrow garden corridor that is defined by two monumental bay laurel hedges that terminate on the door-less side of the main house. (Image One) The metaphorical meaning of the hall-like garden corridor is eventually revealed in the sequential presentation of the main space of the V. Gamberaia, which historians often refer to as the “bowling green.” (Image Two)

When examined in plan view, a long and axial bowling green is the dominant spatial figure of the space and the principal element that organizes the entire garden into subsets of other street-like spaces. The main building of the villa, two double arched arcades, a retaining wall that is articulated like a building façade, the edge of an equestrian stable, a banister railing and another bay laurel hedge, are arranged to reciprocally form and define the edges of the bowling green.

A freestanding grotto fountain caps one end and gives the alley-like space of the Bowling Green a kind of metaphorical beginning and origin point. (Image Three) The other end is left open as a belvedere overlook that propels a spectacular view into the Arno valley below.

A third clue is the interaction of the main house with the other dominant object of the garden, which is a monumental bay laurel hedge that was planted and trimmed to appear like a fragment of a Roman amphitheater. (Image Four) A plan view of the garden helps to reinforce the reciprocal reversal of meaning, because the hedge amphitheater looks more like an architecture element than the actual main house, which is a simple rectangular block. Returning for a moment to Webster’s definition of reciprocity, what the two different elements are “agreeing to do for each other,” is to frame and define a formal water garden between them. It is a space made in one part by a building that is simulating a hedge and on the other side by a hedge that is simulating a historical building fragment—an amphitheater. And this pattern of reciprocal operations and reversals in meaning repeats throughout the garden.

When all of these elements are taken together, one realizes that the Villa Gamberaia is a city fragment, where the narrow garden alleys and the bowling green are metaphorical streets and avenues with plants shaped into living facades and building facades that stand in for urban palaces.

Essentially, two places are produced in the same garden. One, in and of the city. The other, outside the city and in a pleasure garden. By traveling outside of Florence to enter a hillside garden, the observer discovers they have been conceptually re-inserted into a city. The concepts and ideals that shift the observer’s interpretation of the environment unfold within a garden that is also exquisitely beautiful and flawlessly integrated into the surrounding landscape.

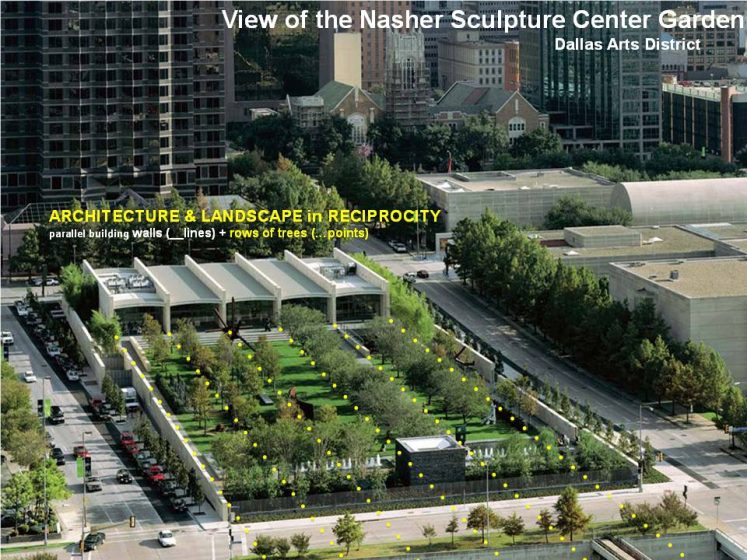

Contemporary Reciprocity: The Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, Texas

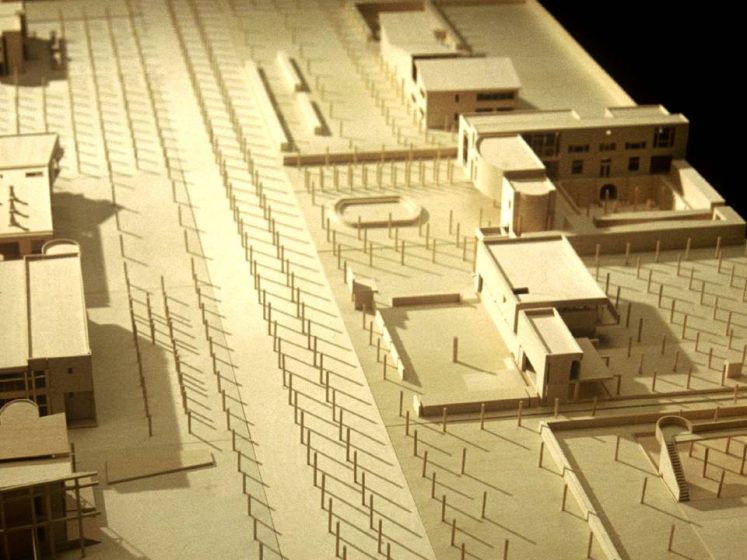

Renzo Piano, architect for the Nasher Sculpture Center (Nasher), referred to the design as a contemporary “ruin” that nature has reclaimed as a garden. Where the Villa Gamberaia demonstrates reciprocity using a classical nomenclature of Roman Amphitheaters and axial alignments, the Nasher utilizes a modern and repeating system of parallel alignments of lines and dots that are reciprocally realized as walls, hedges, columns, and trees.

When viewed in a plan, the dominant quality of the overall arrangement is parallel lines that are the walls of the interior, the exterior perimeter walls of the sculpture garden, or freestanding hedges in the garden that act as spatial dividers and partitions within the overall garden room. Rows of live oak trees (Quercus virginiana) stand parallel with the walls and hedges. These point-lines reciprocally extend the building walls from inside the museum building into the sculpture garden, even as they are simultaneously transformed into landscape points that become the live oak rows and a cedar elm orchard.

To heighten interest, some of the line-points are shifted out of alignment with the building walls in order to adjust for pathways and also allow the imagination of the observer to become involved by correcting the misalignment with their minds-eye. Lines of street trees that lie outside the containment walls of the garden seem typical when viewed as a streetscape. However, when seen from within the garden and in comparison with other garden elements, they read like more rows of the parallels trees and hedges within the garden, that have been multiplied onto the street edges.

In addition to being a place that was exquisitely conceived and impeccably maintained, the Nasher is a textbook case illustrating that the elements of a building can be seen as reciprocally continuous with the elements of a garden landscape.

The net effect of reciprocal design is the work of the mind: inside can become outside, building turns into landscape, and a wall becomes hedge or a line of trees. Taken along with the splashing fountains, shadow patterns on the flawless turf, and the unparalleled quality of the sculpture collection, the reciprocal operations heighten curiosity and enlarge any visit to the center.

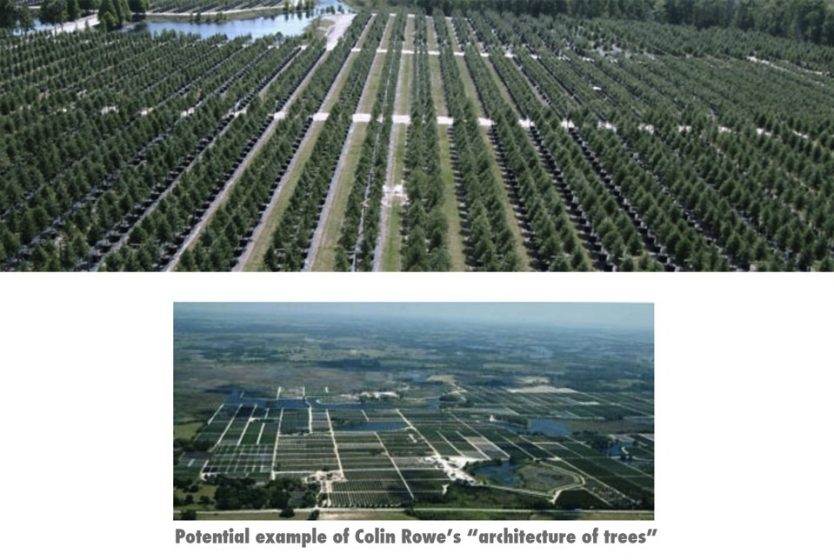

Reciprocity isn’t the only device that is available to mend and restructure the diffuse pattern of the suburban megacity. Urban applications of landscape and building reciprocity as an “architecture of trees” and potential mending fabric for the fragmentary and misshapen spaces of the contemporary city represent another tool that was advanced in late 20th– century writings of Colin Rowe.

“ARCHITECTURE OF TREES”

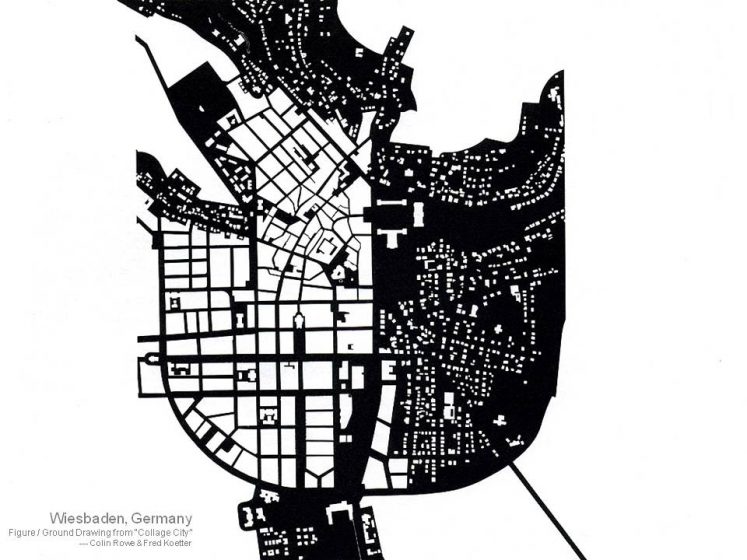

Colin Rowe (1920 -1999) was an architectural historian, theoretician, and professor of architecture at Cornell University, who exerted a significant intellectual influence on world architecture and urbanism in the second half of the twentieth century. His writings and influence revivified the urban design tactics and lessons of the great canonical cities of western civilization such as Rome, Florence, Paris and London.

As a graphic tool to convey and explore patterns of urban space and form, Rowe and his colleagues and followers frequently relied on a particular kind of drawing convention known as figure / ground, that was both a graphic device as well as an intellectual summary of an architectural worldview. The highly reductive, black and white abstractions were useful and consistent to their theoretical interests, considering how the black and white contrast intensified the edge and boundary condition between buildings and the voids that are formed between. The conclusion and summary effect of Rowe’s hypothesis is that cities are essentially building solids and the voids between them. In the same way that architectural space is the reality of a building, to paraphrase Frank Lloyd Wright, cities can also be reduced to the same essential condition. Cities are essentially voids that are deliberately shaped by buildings.

While Rowe’s erudite speculations and the figure / ground drawings that represented them influenced world-renowned architects such as James Stirling, Michael Graves, Leon Krier, Rob Krier (Leon’s brother), Alan Chimacoff, Michael Dennis, Fred Koetter and others, as well as exerting a revolutionary influence on the curriculum of architecture, planning, and landscape programs at Cornell, Syracuse, the University of Virginia, the University of Maryland and individuals within the Harvard GSD, the drawing technique also carried with it the effect of editing out consideration of any role for nature, landscape, and/or the circumstantial interference of topography and/or geography to city form. All cities can be reduced to black and white diagrams of solids and voids. Cities that cannot be mapped by figure / ground, were edited in Rowe’s hypothesis as irrelevant or as anti-cities.

While an entire school of thought formed around the figure / ground-driven view of the “city of (architectural) space,” the same group of academics and practitioners may have overlooked another important lesson that also originated from Rowe’s writing—one that may be an even more provocative offering that could benefit the crisis of the suburban megacity.

While his interests were principally aligned with the European planning models, doubt about their relevance and/or applicability to the diffuse patterns of the suburban metropolis were already unfolding in the American city of the mid-twentieth century. Skepticism about the universal relevance of European cities may have been a by-product of his early teaching years at UT-Austin and the expansive Texas landscape he encountered. He offered the following speculation in an essay he wrote for “The Present Urban Predicament.”

“I would simply like to suggest that the garden may be regarded as both a model of the city; and that the architecture of trees either articulating as parterres as one of the these cases or, amplifying a particular condition as in the other, might well provide some kind of palliative for the contemporary predicament and even some kind of paradigm for the future.”

In the same way that Rowe revivified principles of the European city which are applicable for dense nodes, downtown centers, or dense American cities that have grown, densely, around the originating colonial center, the notion of an “architecture of trees,” and also the idea of the garden as a “palliative” and/or mending fabric for the sprawling and diffuse contemporary city, is an invitation for current generations to potentially extend Rowe’s line of design inquiry and research.

Two projects by Kevin Sloan Studio (of which I am principle and founder), one built and the other unrealized, are case studies that explored “Architecture of Trees” and the potential cohesion it could develop for a diffuse building and landscape formations.

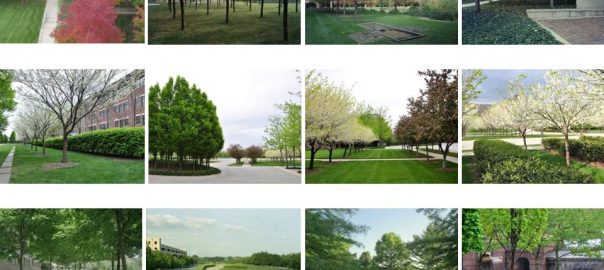

Case Study One: An Architecture of Trees at the Sprint World Headquarters Campus

The Sprint World Headquarters Campus in Overland Park (suburban) Kansas City is an essay on Colin Rowe’s hypothesis for “an architecture of trees.” Situated on 212-acres that were formerly agricultural land, the Kansas City-based Sprint telecommunications company co-located some 13,000 employees within a new campus formation of 21 buildings. While the building design favored a historicist notion of an academic campus in retro-brick, the planning idea for the mixed-use corporate center, produced seven garden quadrangles that were intended to be a spatial, social, and organizational armature for the entire project.

During the master planning process, the physical size of the quadrangles and the building arrangements that formed them was heavily influenced by an interior space-planning strategy that was driven by the area needed for a mid-level executive at Sprint to supervise their particular group on one continuous floor. Consequentially, the typical floor sizes for the office buildings at the Sprint Campus are unusually large—typically 50,000 square feet per floor, and up to 100,000 square feet for exceptionally large corporate divisions.

As a result, the spaces between the buildings were also unusually large and unwieldy for fostering the kind of social interaction between employees that was imagined by the co-location strategy and master plan. The idea to insert an architecture of trees into the seven voids of the quadrangles arose both as a theoretical exploration and one that would also be useful in re-scaling the quadrangles into multiple spaces that would individually be more humane in proportion.

Once within the network of quadrangles, the architecture of trees creates an enveloping effect that rescales the open areas of the quadrangles in some areas, and in others, completely removes the buildings from any perception. Much like the reciprocal metaphors at the Villa Gamberaia, after entering the quads and the highly densified building formations, one is suddenly presented with a landscape world that is without any visual perception of a building. In addition to abstracting notions from the V. Gamberaia, in other situations, we used modern notions of transforming arcade and column formations into tree groves and fountain structures.

In reversing the perceptual reality of the Sprint Campus from the buildings to the landscape in the seven quads, one is invited to imagine removing the buildings to leave only the trees, earth forms, and fountains as the architectural reality of the campus.

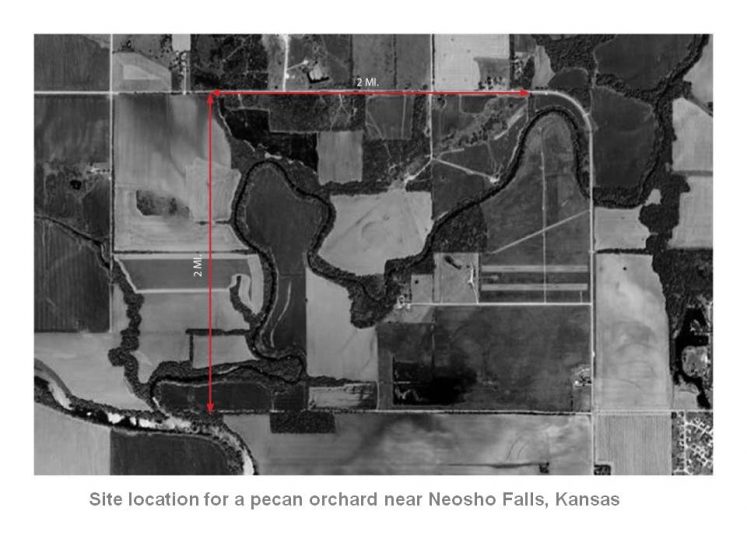

Case Study Two: A Pecan Farm becomes a City of Trees

This project began as an assignment to lay out the orchards of a pecan farm and support buildings on four square miles of river bottomland along the Neosho River in southeast Kansas. In lieu of only an agriculturally established layout, the expansive fabric of trees was re-imagined as a “City of Trees,” to extend Rowe’s hypothesis for an ”Architecture of Trees.”

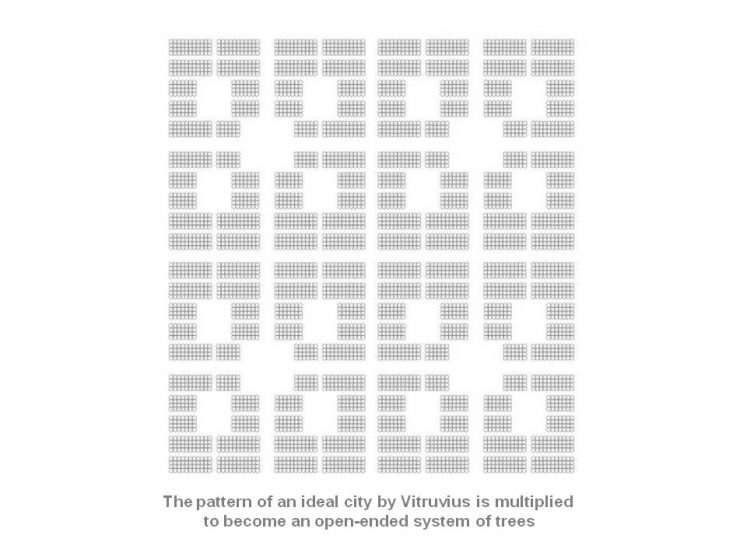

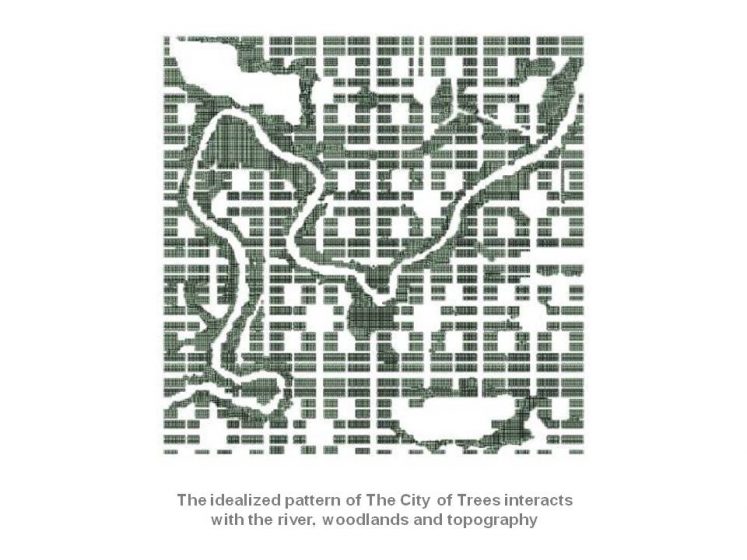

To originate the abstracted city form in pecan trees, the pattern of an ideal city that was conceived by 1st-century Roman architecture, we used Vitruvius and multiplied it into an array. The scale of the pattern was determined by two conditions: 1) the ideal spacing of pecan trees for agricultural production, which was 2) multiplied vis-à-vis the Vitruvian pattern across the area of the entire site.

The insertion of the pattern onto the site forced the ideal pattern and the circumstantial form of the river and its attendant cottonwoods to interfere and modify the design. The project remains unrealized as the landowner reconsidered the economical potential of hydraulic fracking over pecans.

Reciprocity in Drawing as a Design Tool

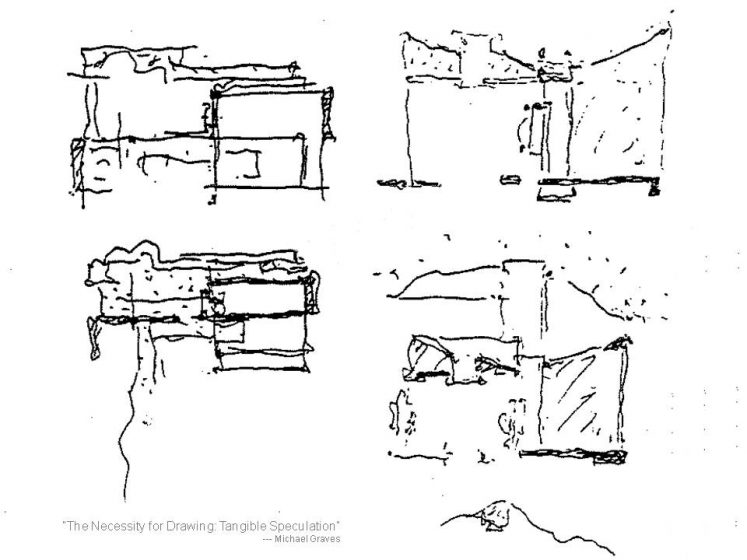

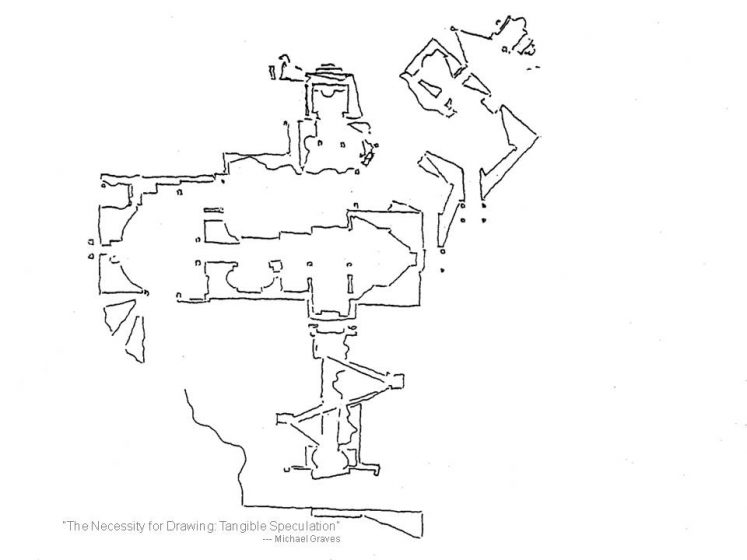

Michael Graves (1934 – 2015) was an American architect who revolutionized modern architecture by repositioning history into contemporary building designs. In addition to his prodigious architectural production and household product designs that included teapots, silverware, and other household items, Graves was an accomplished painter and artist. Drawing assumed an essential role in his architectural production and a particular kind of drawing he referred to as “referential” exploited ambiguities of drawn notations that could be reciprocally interpreted as either a building or a landscape element.

Each of the drawing examples shown above represents different themes, organizational ideas, sets of principles, or even conversations between pieces and fragments that suggest a possible completion or interpretation. The key to the drawing is that the ambiguities remain deliberate, allowing the broadest potential for interpreting what part of the drawing might be the building element and what part the landscape element.

As a demonstration of applying reciprocity as an active part of a landscape or urban design process, Graves’ use of this particular kind of drawing convention may have no equal.

While Graves’ sketches are entirely from his hand, one can easily imagine extending the idea by taking the fragmentary characteristics of an existing site or suburban building arrangement and filling the spaces between with drawn notations that knit, organize, permute and/or transform. By making the drawing insertions similarly ambiguous, the endless speculation that the elements, which knit and transform a fragmentation into a composition, could be additional buildings or landscape devices, is possible.

While Graves may have been definitive in his use of this particular drawing convention for design, much more can be done with it, especially in application towards the vast problems and occasions of the suburban megacity.

SUMMARY

In “Landscape & Memory,” author Simon Schama says, “landscape is the work of the mind.” This elegant and accurate remark clarifies that for landscape to be “landscape,” it must distinctly bear the imprint of the hand of man, distinct from nature. In returning to Robert Campbell’s statement that the entire surface of the earth is now being considered as “one continuous landscape”, by logical extension, we can move to viewing the entire surface of the earth as touched directly or indirectly by the actions of people.

At the poetic level, this notion is compelling and opens up exciting new possibilities for planning, design, and the nature of cities. And at a prosaic level, the statement is less poetry than potential fact, given the threats to the environment that are accumulating from the unmanaged actions of humans.

What is hopeful is not density, but rather how design as a productive and beneficial human could make incremental progress in reversing and transforming the malevolent nature of current building and planning paradigms into a synthesis of building with nature. Indeed, as Campbell concludes, it is potentially a profound new territory for landscape architecture to explore.

Kevin Sloan

Dallas-Fort Worth

Leave a Reply