It takes distance to gain a sense of perspective, and so I find myself sitting in a small market town in the north of England looking halfway across the world at my time living in one of the world’s great emerging megacities, Bangkok.

New investment and land speculation in Bangkok could reshape urban futures…or exacerbate inequalities and relocate risk. So far it is the latter.

From this market town there is a sense of history that goes back over a thousand years, with the architectural and cultural artefacts laid out in the physical structure of the town, and the historical product of massive social upheaval and political struggle evident in the common land that surrounds the town, and the many alms houses that provided early forms of social housing. As enduring as this history is, much of the evidence of the past is missing. During the last 20 or more years, the dockside area has closed and is now rusting, and the manufacturing industry has all but disappeared.

Yet this point of perspective provides a sense of clarity on two enduring tensions: how much we are shaped by our urban history, and how much we continue to find the possibility of radical, transformative change.

The story of Bangkok illustrates a strange contradiction, revealing both the ways in which cities can grow and reshape themselves in dramatic fashion, but also the ways in which cities can become locked-in to a degree of path dependency, whereby alternative trajectories for the future appear constrained by actions of the past and the politics of the present.

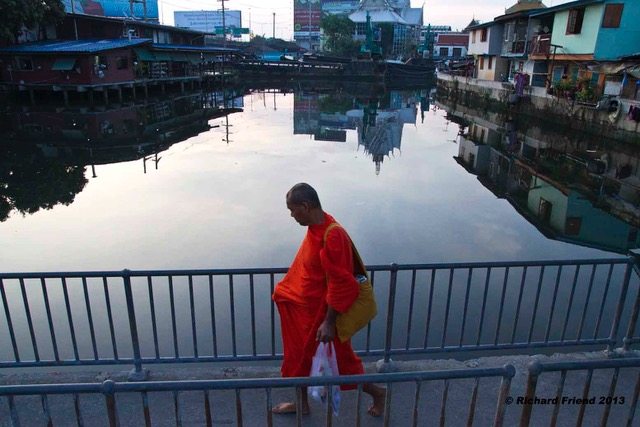

Bangkok is a relatively new city, a mere 200 or so years old. But it is a city that has grown in geographical area and population, and in the global cultural imagination, from the Venice of the East to a form that is increasingly land-based, stretching higher into the sky, lit up through the night. This process of change is visible on an almost daily basis.

Having lived in different parts of the Thailand as well as Laos and Cambodia, I moved back to Bangkok in 2008 just as the impacts of the global financial crisis hit deep. My time in Bangkok was a period in which this relatively modern city went through a fresh round of expansion and intensification, revealing long-standing fault lines of potential conflict, and creating new ones. Arriving in the summer with petrol prices at an all-time high, the notorious Bangkok gridlock seemed to have eased dramatically. People were no longer using their cars, and many who still did were converting petrol engines to liquid gas.

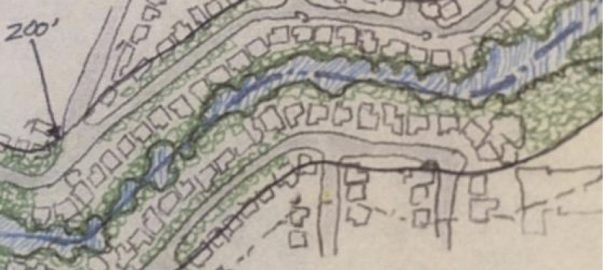

But shortly, the quiet of the crisis was replaced by a new wave of frantic activity. This was especially evident in my own neighbourhood, which was once a relatively distant part of the city, defined by the canal system that joined the main river of the Chao Praya and the low lying floodplain land around it. It was only three or four years ago that the last of the fruit orchards, fish ponds, traditional houses, and small farms disappeared here. Admittedly, they had been hanging on by a thread, but they provided a window into a former time. They were a connection to the wider agricultural landscape around Bangkok. There are still some families that continue to live in much the same way as they have for generations, with houses along the waterways, using small boats to punt themselves and their children across the bank to reach the main urban transport infrastructure. But the waterways were now targeted for a fresh round of land speculation and investment, with high value condominiums and housing estates scheduled to take over the canal banks.

For some reason, it took me some time to appreciate what was happening in my own neighbourhood, but soon it became a regular occurrence to walk down a familiar street, only to find that much of it had disappeared overnight, ready for a new round of construction. The impermanence of the urban landscape—the way in which it could be brought down, reshaped, and reconstructed (sometimes through several rounds) within an astonishingly brief period—was, and is, quite staggering.

Bangkok has witnessed a continued growth in land speculation and investment, drawing capital from around the world but also, significantly, from within the country too. Land speculation has been a persistent theme in the economics of Thailand for many years, and citizens have widely used the phrase “rich in land”, often for those who benefited from the increased market value of what had previously been low-value land. In this way, we have seen farmers sell up to land speculation across the country. This has not always brought the benefits that were expected and there is an enduring motif in popular culture of the rural person who sold their land for quick returns, only to blow the proceeds within a short time and find themselves landless, working as hired labour, worse off than when they started.

Much of Thailand does not have the kinds of land rights that would allow for any opportunity to benefit from the emerging land markets. And so, while investment in land and property involves many people, the costs are often quite clear. Stumbling on an old residential area near the main market that had, disappeared overnight (as if purposefully doing so under cover of darkness), I stopped to talk to the few people that had remained. Initially, they were suspicious, assuming that I was somehow connected to the company that had bought the land to build a condominium. Their story is all too familiar. Despite having lived there for around 90 years, the families had no legal rights. The purchase of the land came as an enormous surprise. There seems to have been no effort to address their rights or their concerns. They told me that the offer of compensation was 3000 Baht (USD$ 86) per household—take it or leave it. Not only were they losing their homes, their connection to place, and their community, but the compensation would not cover any of the costs required to move. And as they said, where else is there left in Bangkok that is affordable and near to work?

Two factors seem to drive the patterns of speculation, and subsequent conversion and construction that follow. Evidently, part of these trends is an apparent attempt to break the path dependence of Bangkok’s transport. The imperative to improve public transport and break the deadlock of traffic gridlock has led to continued investment in the skytrain system. My neighbourhood benefited from such infrastructure. Once considered remote, it is now only a few stops from the glitzy parts of town. Indeed, the glitz has moved out along these routes, and the new urban ideal of the condominium within an overhead walkway stroll’s distance to the skytrain and associated shopping malls has become a physical reality. My neighbourhood is now an area with some of the fastest rising land and property prices—a new investment frontier in the capital.

The sky train demonstrates how investment can reshape traffic. It provides a fast service for getting across the vast area of the city. It also is an alternative to the noise and pollution of the ground level traffic, with air-conditioned carriages and televisions for advertisements. But it is a transport service, and lifestyle, that comes at a cost that is beyond the means of most working families. There is a clear class divide between those who use the service and the rest of the city, that is as strong as the physical separation of the sky train from the ground.

The other factors that have contributed to this reshaping of city transport are much more clearly to do with the way that investment operates in a fast-growing Asian city. Following the maxim of buy low, sell high, money has flowed in such a way as to target cheap land for speculation. Cheap in this context can mean different things—land where ownership is unclear, or where tenancy rights are weak. The relocation of long-established communities is testament to this trend.

An additional feature of the current round of speculation and, indeed, of the history of much of Bangkok and the surrounding provinces, is that much of the land that is targeted is somehow marginal because it is flood prone. Some of the greatest investment in Bangkok and the Chao Praya basin has been on the floodplains, wetlands, and rice fields that flood annually by their nature, and that for a time were protected in state land use plans and zoning. These were easily overturned as capital sought new investment opportunities and high returns; the financial investment, in turn, bought political returns. And so, even the famous King Cobra Swamp, a low-lying wetland on the edge of the city, was targeted for the new international airport. Despite public warnings of the risks this type of land conversion posed to the city of Bangkok, even from the much-revered King, the investments moved forward.

The implications of these investments were revealed in 2011 with the great floods. Many of the industrial parks and housing estates that had been built in the floodways around Bangkok were under water. The impacts cascaded through production chains across the world. At the same time, the pressure to protect the inner city of Bangkok and the international airport led to desperate measures: trying to divert water and halting the flow while maintaining flood levels in some areas. Inevitably, this leads to conflict between those flooded and those spared.

While the new round of investment and speculation in Bangkok illustrates the potential for reshaping urban futures, the most dominant themes that emerge from current trends are of exacerbating inequalities and relocating risk. With limited public dialogue on urban futures, there seems less opportunity for a transformative future that might be more just and more ecologically viable.

Sometimes, reaffirming the basics can have enormous influence. One of my Thai colleagues used to tell me that rights of access to information and participation, and redress and remedy—the Access Rights of Principle 10 from the Rio Summit—would be the foundation for real progress in environmental and social justice. Sitting back in England, I find it’s easy to take these rights for granted. Of course, in Europe, people have come from prolonged, intense political struggle. Their rights have been claimed, rather than granted. From the vast open space of common grazing land that surrounds this market town, to the ability for citizens to organise and petition against local development plans, the landscape here is very different. It does not necessarily mean that outcomes are better, but certainly the odds seem better stacked.

Richard Friend

Bangkok

Leave a Reply