A review of Large Parks, edited by Julia Czerniak and George Hargreaves. 2007. ISBN 1-56898-624-6. Princeton Architectural Press, New York. 255 pages. Buy the book.

“Large parks are priceless, and those cities that do not have an effectively designed one will always be the poorer.” –James Corner

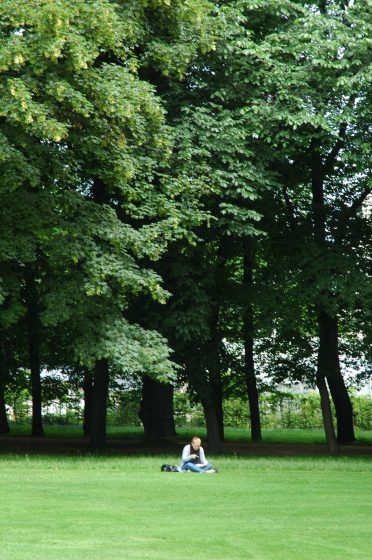

As a Regional Park Planner, I have to say up front that I love large parks, especially those embedded within urban areas. To me, there is nothing quite so compelling as temporarily leaving behind the sights, sounds, and smells of a bustling modern city and slipping into the magical realm of a large park. The jolt to my senses as I transition from one realm to the other is always profound.

When I am in a large park, I wake up to my surroundings—I become immersed in the sights, sounds, and smells of the world around me. As a regular large park visitor, I get to witness the playing out of natural and social processes over time, such that themes of constancy and change become a mirror to my own lived experience. To me, a large park completes a city and a large park completes my city experience.

“Large Parks” is at once thought provoking and sophisticated, helping us understand why large parks are complex—and vital.

That’s why I was so excited to be able to read and review Large Parks, a 2007 Princeton Architectural Press book edited by Julia Czerniak and George Hargreaves. The essays in this volume explore many of the dimensions of large urban parks from a landscape architecture perspective. Large Parks is at once thought provoking and sophisticated in its arguments and narratives. The contributors to Large Parks are some of today’s leading landscape architects, architects, design theorists, critics, and historians.

Large Parks emerged out of a series of events, including a conference held at Harvard University Graduate School of Design in April 2003, where ideas about the significance of size in relation to parks launched discussions relative to the planning, design, and management of past and future large parks. Subsequent colloquia, meetings, discussions, and debates helped to shape the eight essays contained in this volume. Large Parks follows The Landscape Urbanism Reader (2006) and Recovering Landscape (1999) as the third in a series of publications from Princeton Architectural Press that focus on a continuing and abiding interest in landscape.

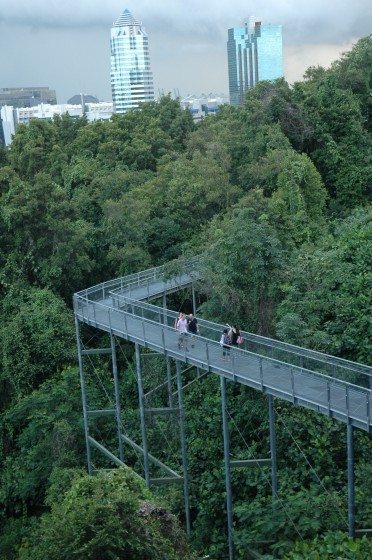

James Corner starts things off with a stimulating Foreword that paints a picture of large parks as “extensive landscapes that are integral to the fabric of cities and metropolitan areas, providing diverse, complex, and delightfully engaging outdoor spaces for a broad range of people and constituencies.” He recognizes that large parks are also valuable for their ecological function, providing habitat for a rich variety of plant, animal, bird, aquatic, and microbial life, as well as essential ecosystem services such as storm water filtration, air purification, and climate regulation. Corner believes that large urban parks function as “green lungs,” helping to cleanse, refresh, and enrich city life.

While these essential functions of large parks have been fundamental to their establishment and on-going public support, Corner states that the creation of most contemporary large parks are now a by-product of expansive development schemes, or as remediation projects for abandoned industrial sites. Unfazed, Corner says these sites present us with enormous opportunities to create entirely new types of public parkland that still provide essential ecological benefits while also embracing often uncomfortable site histories. According to Corner, “the time to reinvent large parks has never been better.”

Corner lays out a central thesis of the essays contained in Large Parks by stating that the ecological, operational, and programmatic aspects of large parks is vitally important, but not very well understood in the development of large urban parks today. These concerns are particularly significant to landscape architects, because large parks are usually designed spaces.

Corner carefully argues that the creation of large parks is a long-term process, subject to revision and change over time. The trick for landscape architects, according to Corner, is to design a large-park framework “sufficiently robust to lend structure and identity while also having sufficient pliancy and ‘give’ to adapt to changing demands and ecologies over time.”

Corner contends that if a large park design cannot address serious issues such as park stewardship, maintenance, cost, security, programming, and ad-hoc politics, that the result will be “the typical bland, populist pastoral pastiche that passes for most recreational open space today, with none of the grandeur, theatricality, novelty, or sheer experiential power of real large parks.”

In her Introduction to the essays, author Julia Czerniak delves deeply into the two words forming the title of this volume—“Large” and “Parks.” Czerniak makes the case that studying parks selected by size allows us look at parks not usually considered together. She argues that due to the present number of large parks in various stages of conceptualization, planning, and development, that a study of large park design, management, and use is timely and necessary.

Czerniak highlights the relevance of “large” in relation to parks, saying that size has practical and disciplinary consequences, and that as the “sole criterion,” the term becomes critical. For the purpose of the essays in this volume, Czerniak defines a park that is at least 500 acres in size as large. This definition in part derives from a statement made by Andrew Jackson Downing during the development of New York’s Central Park that “five hundred acres is the smallest area that should be reserved for the future wants of such a city…”

Czerniak argues that large amounts of land are indeed necessary for ecological resiliency and for economic sustainability, in the sense that today’s parks must be big enough to include the resources for their own making. To Czerniak, size also implies ambition—or the embrace of “big plans” as exemplified by Daniel Burnham in talking about his plans for Chicago. Largeness also requires “considerable energy, vision, commitment, and innovation” by those who work to make these parks happen.

In her discussion of the term “park,” Czerniak acknowledges it is one of the most debated forms of landscape. While early park advocates tied its meaning to green open space with turf and trees, Czerniak notes that now the “character and image of parks, the roles they play, their emergence relative to cities, and their use by various publics has certainly changed.”

Czerniak rightfully notes that, together, “Large” + “Parks” claim a complex conceptual territory which allows for “inquiry at multiple scales and through diverse frameworks that may give rise to how we think about parks today.”

In her contribution to the book, “Sustainable Large Parks: Ecological Design or Designer Ecology?,” Nina-Marie Lister delves into recent shifts in perceptions of ecosystems as deterministic and closed to a more nuanced view of living systems as open, self-organizing, and unpredictable. To Lister, this view of ecological processes demands a new approach to the design and management of large parks. Lister argues that complex natural processes must inform how parks are envisioned to allow for self-organizing and resilient ecological systems to emerge. Lister further argues that designing a park to allow for an “operational ecology” is a basic requirement for long-term sustainability. Lister makes a clear case that large parks within metropolitan areas warrant special consideration and study, and that planning, management, and maintenance must provide for “resilience in the face of long-term adaption to change, and thus for ecological, cultural, and economic viability.”

Landscape historian and theorist Elizabeth K. Meyer builds on Lister’s essay in “Uncertain Parks: Disturbed Sites, Citizens, and Risk Society,” where she discusses how many contemporary large parks are created from ecologically and culturally disturbed sites, such as abandoned factories, landfills, and military bases. These damaged sites are a byproduct of industrial era expansion and modern consumer culture. As such, they are “constituted by debris and toxic byproducts of the city.” Meyer doesn’t ask us to erase these site histories, but rather to view them as spaces to recollect and interpret precise site histories. Meyer interestingly advocates for telling the site’s particular story through park design and programming that reveal and blur the boundaries between “toxicity and health, ecology and technology, past and present, city and wild.” Meyer believes this will allow the public to confront “perceptions of ourselves as a collective of citizen-consumers and as residents of a risk society.”

Architect Linda Pollack’s contribution, “Matrix Landscape: Construction of Identity in the Large Park,” posits that a preoccupation with “thin green veneers” often masks a park’s heterogeneous character. She focuses her essay on the Fresh Kills Landfill, a 2,200-acre site that had served for more than 50 years as New York City’s landfill. An international design competition was held for the redevelopment of the site after it was closed in 2001. The design team Field Operations In New York won the design competition, and in 2006, a draft master plan was released for Fresh Kills Park. The project website stated that “the Parkland at Fresh Kills will be one of the most ambitious public works projects in the world…” Pollack elaborates on the conceptual and representational design strategy used by Field Operations, which she calls the “matrix.” According to Pollack, Field Operations conceptualized the project as a “reconstituted matrix of diverse life forms and evolving strategies” as represented in the spatial framework of threads, islands/clusters, and mats—which, Pollack says, can be understood as the “agent of a fluid set of ecological systems, allowing the interaction of programmatic, cultural, and natural elements to create the complex, synthetic environment.”

In his essay, landscape architect George Hargreaves asks, “why large parks”? To Hargreaves, who approaches the question from a design perspective, size does matter. In his words, large parks “afford the scale to realistically evaluate the degrees of success or failure of many of the issues embedded in public landscapes: ecology, habitat, human use and agency, cultural meaning, and iconographic import, to name but a few.” Hargreaves believes that these issues can’t be understood without considering the physical characteristics of the site itself, and that large parks reveal the importance of the designer’s attitude towards the site and its physical forms and natural systems. He argues, “the extent to which designers embrace or fight the physical history and systems of a site is an important determinant of a park’s long-term success.” Hargreaves provides seven case studies of parks that he has visited and photographed to showcase the work of designers who have grappled with these issues with varying degrees of success.

Landscape theorist Anita Berrizbeitia’s essay, “Re-placing Process,” examines potential associations between making places of lasting identity and value, and facilitating the natural and cultural processes that transform them. Berrizbeitia recognizes that large urban parks are complex and diverse systems that respond to change through time, and as such that they require a process-driven design approach that is open-ended and adaptable. Berrizbeitia believes that large parks “absorb the identity of the city as much as they project one, becoming socially and culturally recognizable places that are unique and irreproducible.” According to Berrizbeitia, successful large parks are the product of deliberate decisions that leave them flexible in terms of management, program, and use, and that they result from “equally conscious decisions that isolate, distill, and capture for the long term that which makes them unique.” Berrizbeitia’s essay captures the relationship between process and place, between those practices that leave a site open to “contingency and change,” and that also capture a place’s “enduring qualities.”

In his essay “Conflict and Erosion: The Contemporary Public Life of Large Parks,” critic John Beardsley writes about the “multiple, often conflicting publics that use large parks” and the possibility of even finding a large park anywhere in the world today that is fully public. To Beardsley, this means a park that is “entirely free and accessible in all places at all times and fully supported by public funds.” Beardsley writes that the complexity of large parks has an impact on how they are designed, such that there is an increased focus on “adaptability to accommodate different user groups at different times.” Beardsley is alarmed at what he sees as the most disturbing trend of all in contemporary parks, which is the increasing expectation that they will pay their own way. He states that “the pastoral park is obsolete; parks are now looking more like commercial landscapes or entertainment destinations…” In the end, Beardsley believes we must reaffirm that “unimpeded access to public parks is a crucial element of environmental justice,” and that we must reclaim large parks as “key features in functioning urban social and ecological systems.”

Editor Czerniak closes the book with her essay “Legibility and Resilience,” in which she looks at how large parks have “significant ecological, social, and generative roles in the contemporary city.” Czerniak argues that successful large parks share two essential characteristics: legibility and resilience. By this she means that a park must be understood in its design scheme, and it must be able to experience disturbance while maintaining its identity and function. Czerniak elaborates on the locational shifts of many contemporary large parks from the urban core to the periphery, where redevelopment lands are often located. She highlights winning schemes from recent international design competitions as case studies, examining how large parks can play vital roles in the city in three ways: as social catalysts, as ecological agents, and as imaginative enterprises. Understandably, Czerniak believes that “the large, the park, the city, and the future are intimately related” and that parks are something that, “both literally and metaphorically, must be cultivated.” She finally calls on those within the design field to understand why parks are necessary, the roles they can play, and how they can look.

The essays in Large Parks are individually and collectively stimulating, thought provoking, and often challenging in their observations and conclusions. The writers are at such a high-level that non-landscape architects may find the material a bit difficult to work through, particularly if they are not familiar with landscape design language and concepts. That being said, a careful read through Large Parks is well worth it, particularly if you are interested in gaining a greater understanding of some of the theoretical and practical considerations that design professionals are concerned with at this level.

As a regional park planner, I am familiar with natural area parks in an urban context, although the parks I work with are not “designer parks” per se; by Julia Czerniak’s standard, they would probably lack “legibility.” That being said, I’ve been fortunate to visit some of the world’s great large urban parks and I can certainly attest to their enduring and irreplaceable qualities, which I now believe stem in large part from successful landscape design strategies that facilitate emergent processes and spontaneous interactions, while also celebrating the familiar and beloved characteristics that bring people back time and again.

It would be hard to imagine the world’s great cities without their iconic parks. However, after reading Large Parks, I better understand the complexities inherent in designing, planning, and managing these often contested public spaces, and I have a greater appreciation of the challenges that they face now and into the future. I would recommend Large Parks to anyone interested in learning about one of our most important and enduring forms of public space from a highly informed landscape architecture perspective.

Lynn Wilson

Vancouver

Click on the image to go to Amazon and buy the book. A portion of the proceeds returns to The Nature of Cities.

Leave a Reply