The problems facing urban waterways are genuinely wicked and often expensive. But there are some simple, affordable, and decentralized techniques that can result in mutual and reciprocal benefit to both people and their waterways.

Albany, NY, Summer 2018. The news cameras closely followed the group of youth as they carried the floating island down to the banks of the Hudson River near the edge of the heavily industrialized Port of Albany. Resembling a mass of plastic tubing intertwined with swamp plants, the island was placed in the water and dragged out with kayaks and canoes to be strategically placed near a massive sewage discharge pipe. Already in the river was a solar panel-equipped barrel-raft, tied to several other smaller floating islands. Once all the pieces were coupled together, makeshift anchors created from concrete blocks were dropped on either side, holding the island in a southward-facing orientation. Now fully powered, a solar powered pump hummed away, blowing beautiful tiny bubbles into the roots of the plants from the murky depths below. The artful-yet-functional techno-ecological hybrid assemblage known as the “artificial floating island” was now complete. As the crowd of onlookers applauded and cheered, I could feel the sense of satisfaction and pride that the youth took in their accomplishment.

With hope, this creation would help to degrade sewage and storm water pollutants that impaired the health of the river. At minimum, it was a participatory project that fostered a sense of care, love, and responsibility between local youth and the well-being of the river. By shining a light on persistent infrastructural problems such as combined sewage overflows, I sought to illustrate the connections between urban ecosystem health and concerns of social justice, access, and equity, weaving in broader conversations about issues of exclusion and alienation in the urban ecosystem. This one small floating island was an encapsulation of the much larger idea of “urban ecosystem justice”.

Urban ecosystem justice

Cities and societies are not sustainable unless there is justice. Urban Ecosystem Justice (Kellogg, 2018) is a framework that views cities as complex adaptive socio-ecological systems and looks at how questions of equity, access, fairness, race and class apply to the biophysical dimensions of urban ecosystems (soil, water, waste, air, biodiversity). By doing so, it makes explicit and moves social sustainability to the forefront of sustainability discourse, while simultaneously challenging ecological alienation by making the urban ecosystem a legitimate, and relevant, topic of study. Both of these issues of social sustainability and ecological alienation are deserving of closer analysis:

Social sustainability

While the urban sustainability movement has had many successes over the past decades, the benefits have been disproportionately befitted affluent residents. This is partly on account of the fact that sustainability discourse over recent years has placed a stronger emphasis on the “environmental” and “economic” aspects of sustainability, largely ignoring or underemphasizing sustainability’s social dimension. This trend has produced a form of “techno-managerial sustainability” that is attractive to business owners, policy makers, and the ruling classes as it promotes a “green” agenda that is at once friendly to capital and conducive to crafting the illusion of community consensus. By relegating the social component, inconvenient questions regarding equity, access, fairness, race and class are glossed over, and fundamental structural socio-economic inequalities are never addressed. As such, the status-quo remains unchallenged and environmental initiatives privilege only affluent communities. Little to no attempt is made to ensure that there is equitable distribution of environmental harms and goods, and in cases when environmental amenities are provided to low-income communities, it often results in the unintentional (or intentional?) consequence of their displacement/cultural alienation (i.e. gentrification). The most extreme form of this manifests in the phenomenon of “urban ecological securitization” (Hodson, 2009), where premium environmental services are provided to the wealthy and the poor are displaced to the urban periphery where they are subject to the brunt of ecological risk, exposure, and vulnerability.

Ecological alienation

Ecological alienation, or ecological rift, is a present-day manifestation of the nature/society dualism professed through modernist ideals and philosophy. Through it, urban residents are profoundly separated from and ignorant of the natural processes and systems that make life on earth possible (i.e. food production, water, composting/decomposition, energy, atmospheric/climatic processes, non-human life). The separation of town and country has relegated these processes and systems to the urban periphery or hinterlands, making them invisible and inaccessible to urban residents. In instances where “remnant” ecologies remain in cities, they are commonly made inaccessible through enclosure, poisoned, degraded, or otherwise de-valued. Where environmental education does exist in cities, it teaches about the environment and nature as external to the city, with urban environments being considered unworthy of study. Likewise, definitions of “the environment” seldom are extended to include social and human processes. The combined influence of these conditions produces in both children and adults what is referred to as “ecophobia” (Sobel, 1996), or fear of ecological systems and processes. When a citizenry has no sense of inter-relation, love, concern, or responsibility for ecological systems, they cannot be expected to act in their defense.

Urban ecosystem justice importantly situates itself within a citizen-center, grassroots context. In this regard, it focuses on exploring and creating mutually reciprocal symbioses between ordinary citizens and urban ecologies from the ground up, an angle typically not explored from top-down planning and policy perspectives. By applying a DIY ethic to the “ecology of cities” paradigm developed in the discipline of urban ecology, humans are seen as central and integral to urban environmental processes. In this regard, urban ecosystem justice can be thought of a “science of cities for the people”. Urban water issues are good starting place for seeing how an urban ecosystem justice response may be operationalized.

Water in cities

Water is essential for life: for drinking, irrigation, fishing, washing, transportation, trade, and industry. It’s no wonder that most cities are built on the edge of a river, lake, or ocean, providing the lifeblood to urban activity. Over time, however, on account of the growth of cities, industrialism, and auto infrastructure, waterways have become increasingly abused and neglected, treated like open sewers to carry away all manner of urban waste products. Correspondingly, the health of urban waterways has suffered, causing them to become unsuitable for either swimming or fishing.

Take New York’s aforementioned Hudson River as an example. Once a thriving tidal estuary with abundant aquatic life that sustained people over thousands of years, in Albany there are now advisories against eating most fish species out of the river, a consequence of PCBs (Poly Chlorinated Biphenyls) leaching from industrial sites and building up in the food chain. To make matters worse, the construction of Interstate Highway 787 in the mid-twentieth century has all but cut off resident’s access to the riverside, a tragic decision made to facilitate suburban commuting at the expense of people’s connection to the river. The inaccessibility and poisoning of waterways has had a disproportionate impact on lower-income urban residents, who frequently rely on fish caught from them for sustenance and survival.

The health of urban waterways is further impaired by polluted storm water runoff. On account of the tremendous amount of impervious cover (asphalt, concrete, and rubber and tar roofs) in cities, very little rainwater is absorbed into soils. The majority of it rushes off streets roofs and flows rapidly into storm drains, carrying a toxic mixture of gas spills, fertilizers, pesticides, and dog droppings. In older cities, storm drain pipes are often combined with sewers. During heavy rain events, these will spill over into local waterways, resulting in what’s known as a CSO (Combined Sewage Overflow). This noxious mixture of storm water runoff and sewage contributes to significant water quality issues in urban water ways including eutrophication (excess of nutrients) and the spread of disease.

The problem of storm water runoff and sewage overflows can seem enormous and daunting. Small actions such as building floating islands can give people the feeling that they have the ability to make an impact, even if it is just a first step.

Return to the island

Such was the impetus for the design and creation of the Artificial Floating Island, or AFI (Yeh, 2015). The AFI was a project of the Radix Ecological Sustainability Center, an urban environmental education non-profit based in the South End of Albany. It was carried out in conjunction with Radix’s “Ecojustice Summer” program, a five-week summer youth employment immersion that combines community gardening with sustainability justice education and outdoor adventure. The AFI’s construction was made possible through a $5,000 award from the Albany Water Board, who opted to fund an environmental benefit project in lieu of paying fines to the Department of Environmental Conservation for failing to report a sewage discharge the previous summer. While Radix had built many AFIs previously, it had always been done on a shoestring budget. Consisting of bundles of recycled plastic bottles, they had been jokingly referred to as “floating trash islands”. Now with some financial backing, we could construct the Cadillac of floating islands complete with a component of active aeration.

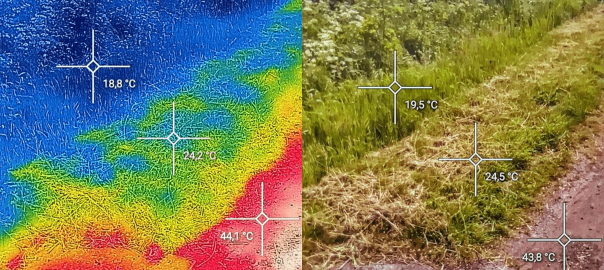

Here’s how it worked: “islands” kept afloat by rolls of irrigation tubing would support native wetland plants affixed by zip-ties. While floating in a contaminated water body, the plant roots would grow down into the water column and be colonized by beneficial bacteria. A solar panel mounted on a floating dock powered an air pump that would oxygenate the water and support the microbial community. Sewage and other pollutants flowing through the roots of the plants would be consumed by bacteria while the plants themselves would uptake nutrients from the water, transforming them into a harvestable biomass. Inspired by “natural” floating islands that help to purify lakes and ponds, its design is simple, elegant, and effective. AFI technology had advanced considerably, with a substantial body of published studies proving their effectiveness.

The islands, built cooperatively by the Ecojustice youth, were “incubated” in stock tank ponds at Radix for several weeks before being deployed. This not only gave the chance for both plants and their attached microbes to mature, but also allowed to youth to develop an intimate and daily familiarity with the system, seeing it grow and develop over time. Not only did the island function as a tangible model of participatory, problem-based, and experiential learning, it also spurred interest in the history and ecology of the river itself, an effective means for challenging ecological alienation among the youth who for many, despite having grown up in Albany, had never actually stood on the banks of the Hudson, let alone gone out into it on a boat.

Conclusion

The problems facing urban waterways are genuinely wicked, some of which can only be solved through multi-million dollar infrastructural upgrades performed by municipalities. How then, is it possible for the average urban resident to have any impact on this problem? The good news is that there are a number of simple, affordable, and decentralized techniques that can be carried out that will result in mutual and reciprocal benefit to both people and the health of their waterways.

In addition to floating islands, these include rainwater collection, de-paving, and rain gardens. While the impact that any of these might have by themselves is small, collectively and synergistically they can produce significant results. It is critical to point out that these decentralized approaches must be done in coordination with broader political action aimed at “turning off the tap” of storm water and sewage pollution—residents cannot bear the burden of “mopping up the mess”. More importantly, citizens taking any kind of initiative towards improving their relationships with local waterways has profound symbolic and educational value. Just thinking of impaired waters as anything other than hopelessly polluted and deserving of care creates a powerful counter narrative to the idea of urban waters as being dead, toxic, and beyond salvation—an essential first step towards building urban ecosystem justice.

Scott Kellogg

Albany

Citations

Hodson, Mike, and Simon Marvin. “‘Urban ecological security’: a new urban paradigm?.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33.1 (2009): 193-215.

Kellogg, Scott. “Urban Ecosystem Justice: The Field Guide to a Socio-Ecological Systems Science of Cities for the People”. Ph.D. Dissertation. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 2018. ProQuest.

Sobel MEd, David. Beyond ecophobia: Reclaiming the heart in nature education. Orion Society, 1996.

Yeh, Naichia, Pulin Yeh, and Yuan-Hsiou Chang. “Artificial floating islands for environmental improvement.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 47 (2015): 616-622.

Leave a Reply