It is tempting and comforting to think that after each disaster, the tragic loss of life, the loss of livelihoods and the loss of productivity awakens the political class to do things differently. Sadly, it seems not to.

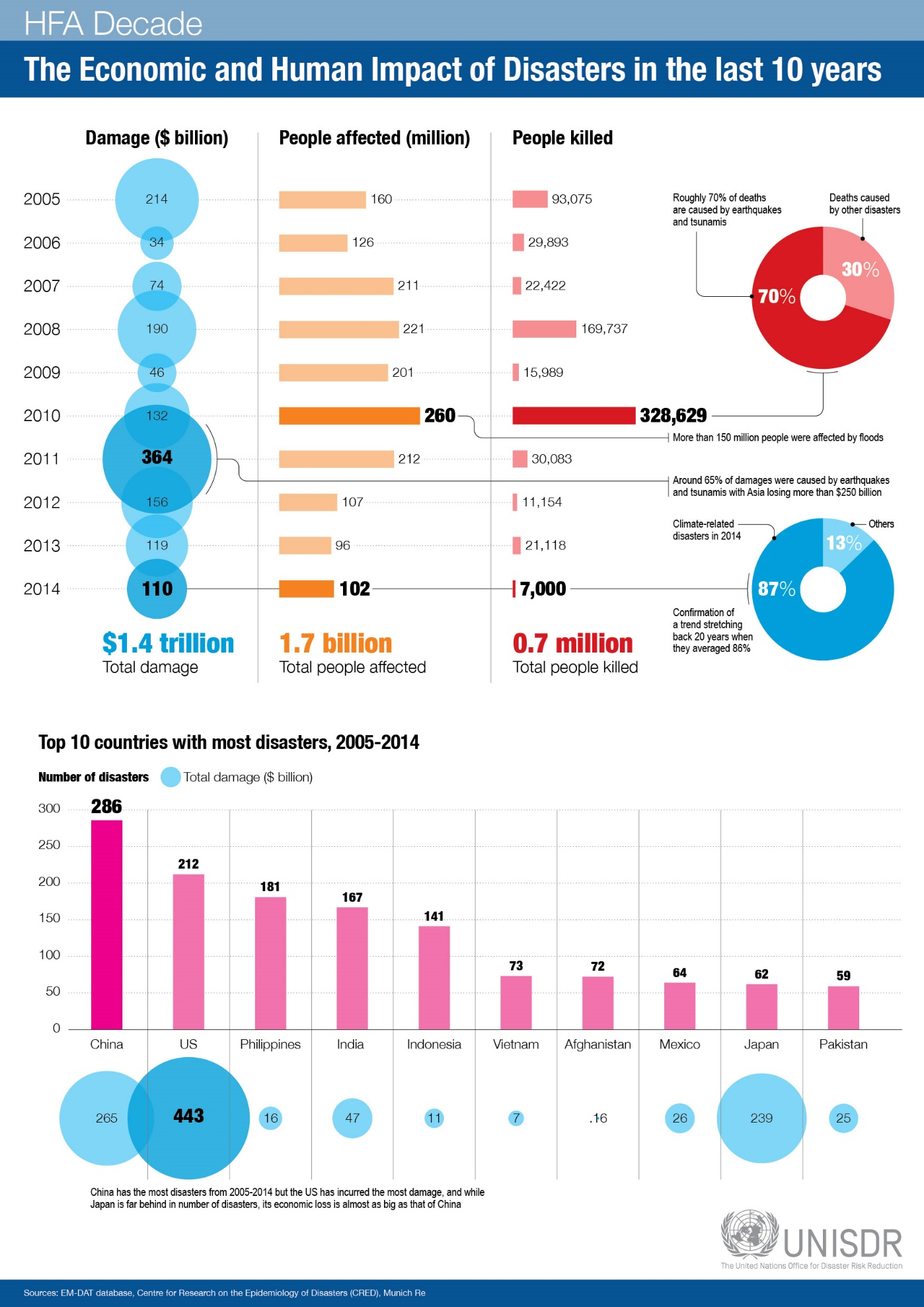

This destruction is obviously a tragic event, which usually leads to thousands of fatalities, injuries and displaced people, loss of income and livelihoods, loss and interruption of essential basic services (e.g. water, sanitation, electricity, food supply, transportation, telecommunication, internet, etc.)—all of which also culminating in significant losses to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, these disasters, by transforming the existing risk to reality, reduce this existing risk to zero (as the risk embedded in structures, infrastructure and livelihoods has materialized). Hence, these disasters present an “opportunity” to rebuild back better[i] cities, where the hard infrastructure and housing is resilient to disaster risk and where the root causes of disaster and conflict (including inequality, exclusion, unplanned urbanization, weak governance and environmental degradation) are mitigated or avoided rather than reintroduced into the reconstruction and rebuilding processes.

The post-disaster recovery and reconstruction process is often done in a rapid manner, without sufficient time for planning, and is often significantly influenced by the vested interests of local, national and international private sector actors and their partners in the public sector. In many global south countries, the repayment of public debt consumes a large percentage of the budget, thereby leaving limited funds for governments to invest in development initiatives much needed to mitigate conflict drivers including socio-economic exclusion, youth unemployment and rising inequality. In many of these countries, this situation is exacerbated by prevailing weak governance practices, which hinders the private sector from fulfilling its potential role in being an engine for economic growth and rising employment.

When unplanned, the recovery and reconstruction process reintroduces conflict risk drivers into future societies. In addition, even when the reconstruction and recovery process have accounted for natural hazards by building against earthquakes and flash floods for example, it often misses the opportunity to mitigate existing disaster risk drivers including poverty, environmental degradation, rapid unplanned urbanisation and weak risk governance.

On the other hand, a planned and transparent recovery and reconstruction process, based on inclusive principles, that aim to reach the most disadvantaged in society, can significantly mitigate disaster risk drivers especially when it is based on “build back better” principles. Learning from the mistakes of the past, and trying to mitigate disaster and conflict risk drivers; urban communities, affected people and practitioners call for the following good practices to be accounted for in the reconstruction and recovery processes [vi]:

- Housing rehabilitation and reconstruction, based on build back better principles that account for natural hazards and green building considerations.

- Housing land and property rights restitution and protection.

- Urban livelihood recovery and the creation of decent jobs across society including for youth and women. This should also include training for unemployed and to new entrants to the job market to ensure that skills match market needs.

- Protection of historic urban areas and cultural heritage areas, while balancing the needs fort the local population and the stresses of economic growth and development.

- Restoration of basic services including water, waste water, energy and transportation while accounting for natural hazards and climate change considerations.

It is tempting and comforting to think that after each disaster, the tragic loss of life, the loss of livelihoods and the loss of productivity awakens the political class to do things differently, to mitigate conflict and disaster risk drivers, through some form of a “NEWer, Greener, More Inclusive Deal” that aims to leave no one behind, or at least not so many behind. However, in many parts of the world, both developing and developed, both rich and poor, the exact opposite is taking place: Disasters have become the opportunity to push for further rapid privatization of basic state services and further deregulation, with short term profits as the main incentive. An incentive that has shown once and again that it is the creator and feeder of conflict and disaster risk drivers.

These trends can also be seen at the international, developed country level, including for example meeting the commitments for financing climate change action as recommended by successive climate change conferences. Developed countries are still far from reaching the goal of mobilizing $100 billion to developing countries by 2020 [vii], to ensure that investments and financial flows worldwide are aligned with climate and development objectives. The climate action-financing gap exacerbates the existing situation where trillions of dollars of investments are directed at actions that ultimately damage our climate and contribute to conflict drivers and disaster risk drivers. Indeed, this is difficult to achieve when investment decisions are funded by agencies focused on shareholders’ short term profits.

The outcome, and the fate of our societies, will be determined by how much we can come together to demand and enforce more resilient, inclusive, greener and more humane reconstruction and recovery processes. In short, recovery and reconstruction processes affect us all, and as such are everybody’s business, and are too important to be left as the exclusive terrain for international finance and aid agencies!

Fadi Hamdan

Beirut

Notes:

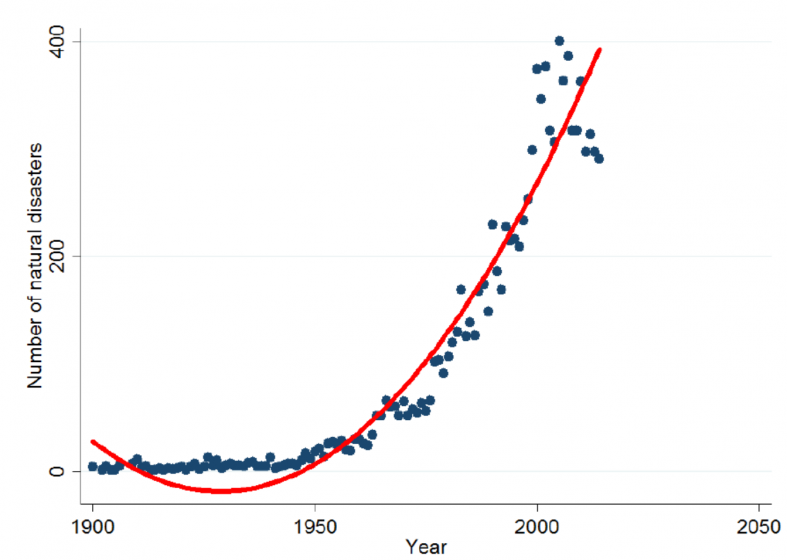

[i] Build Back Better is defined by the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN-ISDR) as “the use of the recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction phases after a disaster to increase the resilience of nations and communities through integrating disaster risk reduction measures into the restoration of physical infrastructure and societal systems, and into the revitalization of livelihoods, economies and the environment”. [ii] The fiscal impact of natural disasters, Ian Koetsier, Utrecht University – school of economics, Discussion Paper Series nr: 17-17, 2017, https://www.uu.nl/en/organisation/utrecht-university-school-of-economics-use/research/working-papers/discussion-papers-2017. [iii] UNISDR Disaster Statistics, https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/disaster-statistics. [iv] Unhealthy conditions-IMF loan conditionality and its impact on health financing, Gino Brunswijck, European Network on Debt and Development, 2018, https://eurodad.org/files/pdf/1546978.pdf. [v] Don’t owe, shouldn’t pay, The impact of climate change on debt in vulnerable countries, Jubilee Debt Campaign, 2018, https://jubileedebt.org.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Dont-owe-shouldnt-pay_10.18.pdf. [vi] E.g. The New Urban Agenda, United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, HABITAT III, QUITO 17-20 October, 2016, UNHABITAT, 2017, http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf. [vii] At COP24 Paris Proved its Worth, Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, WWF, 2018, https://medium.com/@WWF/at-cop24-paris-proved-its-worth-93846e8481de.

Leave a Reply