We have come to realize that a greener, safer and healthier world starts at a young age and that the schoolyard is the perfect place to provide urban nature for everyone, regardless of any children’s home situation. The movement for green schoolyards is on!

In my last blog, A Sense of Wonder: The Missing Ingredient to a Long-Term Value for Nature?, Bronwyn Cumbo and I questioned what types of childhood experiences instill a lifelong value for nature and promote stewardship behavior later in life. It turned out that children who experience a sense of wonder through direct contact with nature are more likely to develop a life-long respect and value for the existence of natural areas, the habitats they contain and the species they support. That in mind, you can imagine how happy I am to share the making of the first Tiny Food Forest in the Netherlands—at a primary school!

This story begins on a grey afternoon in January 2018. Twenty-six 9 and 10 year-olds were nervously wobbling on their chairs in their classroom on the 1st floor of a primary school in the town of Ede the Netherlands. The sound of low whispers and hushed giggles, heads curiously turning to the door. Were they expecting a visitor? Indeed, they were. Today, a real scientist would visit their class, as part of the Scientist in the Classroom program (see Box 1). The children were as excited as if Santa himself was about to walk in.

And that’s when I rocked up: Hardly five feet tall, wearing an orange jumper and a bright blue backpack. No lab coat, no looking glass—what kind of scientist was this? The children were told to bring a measuring cup, so surely something sciencey was going to happen. At this point, the children did not know about the sacks filled with sand, soil and pebbles that were awaiting them outside. But as in real science life, before we headed out to test and explore, we first asked ourselves some burning questions and started collecting all presently available knowledge on the topic. On we went.

Box 1: Scientist in the Classroom

Scientist in the Classroom is a program that stimulates “research-oriented learning” at primary schools, developed by several universities in the Netherlands. Scientists interested in engaging with a different audience, are trained in “research-oriented learning” and supported to shape their knowledge and expertise for education at primary school level. Based on their own research, scientists develop a class to teach to 10 to 12 year-olds which is offered via the Scientist in the Classroom website at the start of the school year. Primary school teachers pick their favorite class and are connected to the scientist to discuss about expectations and details, and if it is a match, pick a date. The class is evaluated, and if the scientist would like to, offered again the next year.This is the third year I participate in the Scientist in the Classroom program, and I highly recommend it. It is not only a fun and rewarding way to interact on your research with a new audience; it is also a way to “test” your research and its societal relevance in particular. It made me think: Am I asking the right questions, am I evaluating the right solutions? Teaching in 3rd and 4th grade provided me insight on how children perceive changing weather patterns, what their worries are about urban heat and wet feet, and in which direction they search for solutions. And most importantly, it taught me the need to design spaces that are fun to use and that encourage interaction.

The topic I brought to class was “Climate and Wet Feet”. Upon asking about personal experiences with wet feet after heavy rains and hot and cool spots during last summer’s heat wave, about 26 out of 26 (OK, 52 actually…) hands were raised. Who says discussing climate change impacts should be left to the “experts”? Or that people do not notice, let alone care about, the consequences of changing weather patterns in their daily lives? From the stories that followed from my questions it turned out that all children in class had experienced and held a perception of urban heat and flooding. It became clear that they noticed how nature, from gardens to forests, plays a role in reducing the heat and wetting their feet. Of course, this was exactly what I was after: Talking about and experiencing how greenspace can help deal with heat and flooding in built-up areas. As one girl mentioned:

“The shady garden of my grandparents’ house in the countryside is so lovely in summer.”

—Grade 4 child of Panta Rhei Primary

A boy told us how he would jump puddles on his way to school after a heavy shower, which immediately got supported by his classmate who used to live on the same street. This in turn led to upheaval about their own schoolyard, and the children got up from their chairs to take me to the classroom window for a peek at their view: A large, square yard covered with concrete tiles and the odd play set. There were two tall trees breaking the scene, but they seemed somewhat out of place with their roots all covered in concrete. Unsurprisingly, the trees could not prevent the rainwater from building up at their feet and around the stormwater drain. The teacher was right when she told me, in preparation of this class, that an afternoon about green solutions for climate change impacts would be very welcome.

This was the moment to return to the theoretical part of my class on Climate and Wet Feet. Teaching the children about the consequences of changing weather patterns at the local scale, comparing their own experiences to those elsewhere in the world, they were quite impressed by the images of flooded neighborhoods in the UK and families carrying their belongings high above their heads in the streets of Indonesia. But also, the image of a man being rescued from his car in the Netherlands and a picture of a Dutch student in his swimming trunks moving through the street on an airbed got the children’s attention. This was not something that was far removed from their own personal lives.

To link these climate change impacts to the role of nature in our home environment, we watched a short animation titled “Tile out, plant in!”. In two minutes, the animation shows the negative effects of paved private gardens: rainwater cannot infiltrate the soil, leading to increased pressure on the sewage system. Biodiversity suffers as paved backyards do not offer much in terms of habitat for hedgehogs, birds, bees and butterflies, and the animation also illustrates how paved yards increase the urban heat island effect which effects people as much as animals, especially the young and elderly. Luckily the video did not leave us all sad and gloomy, instead we felt inspired and ready for action! It showed how easy it is to turn around this process of paving and start a process of planting, starting at our home environment. Hence the title: “Tile out, plant in!”.

A science class does not come without fieldwork, so off we went, into the schoolyard, to collect our data. I had prepared a water infiltration experiment in which the children would pour water into similar sized pots filled with soil, sand and/or pebbles and measure the time needed for the water to seep through as well as the difference in volume between the water poured in and the water that had seeped out. The children noted down their results on a scoring sheet, repeating the experiment with different types of fillings (soil, sand or pebbles). We took our data sheets back to the classroom and discussed the results. Soil turned out to be the winner, with most time needed for water to seep through and most water retained by the soil—meaning less water ended up on the pavement for release into the sewage system, and also that water is released more slowly which relieves pressure on the system (especially relevant for peakflow).

So, what’s next? How can we put our findings into practice? It was time to distill and formulate our recommendations. The children came up with numerous ideas to tackle their paved “Wet Feet” schoolyard and turn it into a green, friendly and explorative one, inspired by DIY solutions such as rainwater harvesting and green schoolyard designs of which I showed them examples in my presentation. Most important to the children, was to create a nicer space to play. Yes, they understood the benefits that a green schoolyard provides for stormwater drainage capacity, ambient temperature and biodiversity. But what mattered most to the children, rightly so, was to be able to play and explore together in a green and surprising environment with slopes, tunnels, sand hills and shaded seats of which the looks change with the season.

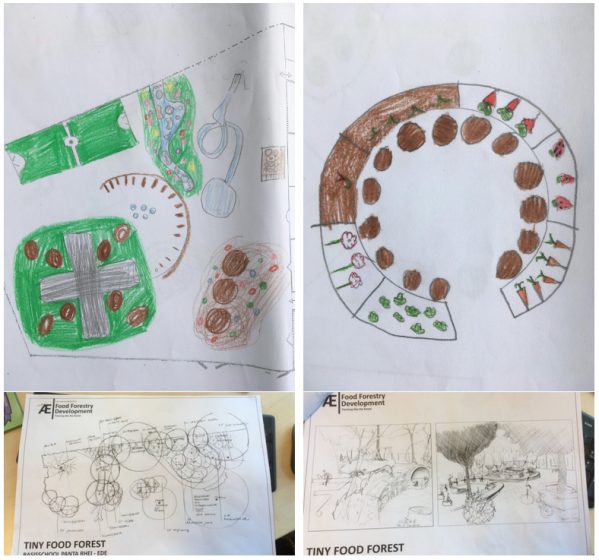

To make sure we all actually experienced what it is like to play in a green schoolyard, the teacher and I planned a second meetup to take the class for a visit to a nearby school that already implemented a green schoolyard. It was much smaller than their own schoolyard but featured an insect hotel, kitchen garden, a tunnel made out of willows, a little stepping stone path with mosaic tiles and an outdoor kitchen. You should have seen the children go. Their play turned into one full of exploration and wonder, and also collaboration. Green schoolyards have been found to improve children’s physical, social and emotional well‐being, including less bullying and a greater feeling of safety (Kelz, Evans, and Röderer 2015; Bates, Bohnert, and Gerstein 2018; van Dijk-Wesselius et al. 2018). Back in the classroom, the children started making designs for their own schoolyard which they would finish in the following weeks.

“Look at these bugs! I want to take one home.”

—Grade 4 child of Panta Rhei Primary

The teacher and I were getting really excited to get this started, but knew we depended on the support of other’s, to push it forward. So, we got to work. The teacher attended a conference on green schoolgrounds and started to warm up her colleagues and school directors to the idea. I knew that local food production is high on the agenda for Ede municipality, so I asked a friend working with the municipality about their support programs for schools with a wish to become ‘greener’. She pointed out several options, from kitchen gardens to daily fruit deliveries. She also put me in touch with the local nature education organization Het Groene Wiel (The Green Wheel) for which the timing could not have been better: their national umbrella organization IVN (Nature Education Institute) had just received a donation to plant 100 Tiny Forests and 2 Tiny Food Forests and for the Tiny Food Forest they were urgently looking for a school. A Tiny Forest is a tennis court sized forest with trees planted closely together in order for them to grow rapidly, and quickly become an ecosystem that does not need any management. A Tiny Food Forest is a similar sized but less densely planted forest in which every plant is, or carries something edible: berry bushes, fruit trees, nut trees and herbs. This makes a Tiny Food Forest perfect for interaction, play and educational purposes.

From then on, things started to move fast. All school staff were gathered for a meeting to be introduced to the Tiny Food Forest concept and to discuss the options for their school, the board was approached, and Het Groene Wiel mobilized their Tiny Forest team. For Ede municipality, this was a perfect opportunity to further promote their image within the leading agri-food center of Europe: Foodvalley. With this team of enthusiasts, a new collaborative project was born. Children, parents, neighbors—everyone got involved. A designer was contracted to work out the plans and after summer break the first preparations took off. Materials were collected with the help of parents and staff and also residents of the school neighborhood came out to help clear the old schoolyard, removing concrete tiles for reuse in the new outdoor kitchen and the construction of a hilly herb garden. Physically, it all got done in a couple of days.

The first Tiny Food Forest of the Netherlands! The festive official opening took place on a cold day in November. The designer, me and a team of Het Groene Wiel volunteers gathered early to plant the trees, bushes and herbs of many different species that would become the Tiny Food Forest. Children had the opportunity to name and plant a tree so they could follow the growth of “their” tree throughout the school years. The school director and my friend from the municipality came out to take a peek before everyone arrived for the official opening. It was a grand opening with tv cameras and photographers from the national youth news channel and local news. Children and parents were excited about everything that was happening around them, maybe even a little nervous? There was a speech from the municipality’s spatial planning councilor, the school director and two children recited a poem about their new green schoolyard. And of course, the Tiny Food Forest needed to be named! In the weeks before the official opening, the team had organized a schoolwide competition in which the children could propose a name for their new schoolyard, followed by a voting round. And today the winner was announced: Het Bosplein, which is Dutch for the forest (bos) yard (plein). The student who invented the name received a big round of applause and together with the 4thgrade teacher, officially opened the new schoolyard by revealing an information board showing facts and illustrations about the Tiny Food Forest.

And what’s next? Hopefully the forest will grow tall and strong to become a place to explore, play in and enjoy—a real place of wonder for the children. It will certainly become a green addition to the neighborhood and a change of scene for staff and children alike. Teachers will find new ways to include outdoor schooling in their teaching, supported by Het Groene Wiel, and children will come home with new stories and adventures. Several of them will become junior rangers of their own food forest. In terms of biodiversity monitoring, Wageningen University started a monitoring project around Tiny Forests and will include the Bospleinin its inventory. Also, IVN, the national Nature Education Institute, will follow all that happens around the Tiny Forests and publish the Tiny Forest newsletter. For the town of Ede, it is great to have this as a national first and I was told they already increased their 2019 budget for greening schoolyards. Similar developments have taken place in cities across the country. We have come to realize that a greener, safer and healthier world starts at a young age and that the schoolyard is the perfect place to provide urban nature for everyone, regardless of any children’s home situation. The movement for green schoolyards is on!

Marthe Derkzen

Amsterdam

References

Bates, Carolyn R, Amy M Bohnert, and Dana E Gerstein. 2018. “Green Schoolyards in Low-Income Urban Neighborhoods: Natural Spaces for Positive Youth Development Outcomes.” Frontiers in Psychology9: 805. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00805.

Dijk-Wesselius, J.E. van, J. Maas, D. Hovinga, M. van Vugt, and A.E. van den Berg. 2018. “The Impact of Greening Schoolyards on the Appreciation, and Physical, Cognitive and Social-Emotional Well-Being of Schoolchildren: A Prospective Intervention Study.” Landscape and Urban Planning180 (December): 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.08.003.

Kelz, Christina, Gary William Evans, and Kathrin Röderer. 2015. “The Restorative Effects of Redesigning the Schoolyard.” Environment and Behavior47 (2): 119–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916513510528.

Leave a Reply