A sustainable ecology of cities is possible when we successfully combine environmental and socio-economic dimensions equally in our plans and actions. In fact, it is the extent of their integration and inclusion that should form a criterion by which we evaluate our success.

It is with this objective that I consider building relationships collectively between people and with nature as an important mission. This mission includes an understanding of such relationships and networks of interactions, particularly those that develop in the process of collective interventions by citizens on demands pertaining to social and environmental justice and how they contribute to the larger interest of sustainability of cities.

I would like to view cities from social and environmental perspective and understand how the two together constitute a necessary condition, and what their union means for the achievement of a higher state of sustainability. The two are inextricably entwined and neither is exclusive. Thus, a sustainable ecology of cities is possible when we can successfully combine environmental and socio-economic dimensions equally in the plans and actions that we pursue. As a matter of fact, it is the extent of their integration and inclusion that form a criterion by which we evaluate the value of our work and engagements.

Very often we find ourselves absorbed into zones of comfort and complacence, engaging in issues and places that have already been developed or achieved exclusivity. But to get out and engage with situations of instability and discomfort, dealing with the invisible yet perceived barriers across city landscapes, and their unification, is indeed challenging.

After all, what can be more equal between nations, influenced by neo-liberal globalisation, than the question of land mis-utilisation, exclusionary city planning, and the deplorable state of the environment in which vast numbers of people are discriminated and subject to climate change risk. It is for these reasons that the local struggles of the marginalised and discriminated people for equality and sustainability, across borders and nation states, are indeed global in their essence and spirit.

What we are deeply concerned about is the constant division of our cities into disparate fragments, both in social and spatial terms. Polarisation of people and communities in terms of their religion, race, caste, class, faith, gender, nationality is leading to social instability and tension. Indeed, our cities are producing and reproducing backyards of exclusion, discrimination, hatred, neglect and abuse; even natural habitats are being systematically destroyed leading to increasing levels of social intolerance and climate catastrophe, thus undermining the very idea of cities and their sustainability.

As these conflicts begin to dominate the city landscape, we are compelled to intervene, particularly on behalf of the excluded, discriminated, and much abused backyards of people and places that are, in most instances, situated in the borders, edges, peripheries, and margins.

Our discourses on cities have relied on the understanding of social relationships and how the modes of production have influenced their formation. In support this statement, I would like to refer to David Harvey and his book Social Justice and the City, when he quotes from Karl Marx: “The totality of these relationship of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life, conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. In terms of Marxist terminology, the urban and the process of urbanization are simple superstructures of the mode of production (capitalist or socialist)”.

Further, in the same book, Harvey has analysed social relations, built form and environment and how each influences the other, but his reference to environment is restricted to built-environment and does not include the natural ecosystems. I quote: “Urbanism may be regarded as a particular form or patterning of the social process. This process unfolds in a spatially structured environment created by man. The city can, therefore, be regarded as a tangible, built-environment- an environment which is a social product.”

Interestingly, Pickett, Cadenasso and McGrath in their book, Resilience in Ecology and Urban Design, quoting McGranahan and Satterthwaite, present a much wider understanding of the environment. I quote: “A great deal of the urban sustainability literature tends to promote the so-called ‘brown agenda’ of environmentalism, which emphasizes the need to solve immediate needs of the billions of people who live in degraded, unsanitary conditions and grueling poverty, while the ‘green agenda’ emphasizes protection and enhancement of ecosystems to support future generations and other species. Reconciling green with brown agenda issues, however, is at the heart of more encompassing viewpoints on sustainability, recognizing that poverty and environment conservation are inextricably entwined (McGranahan and Satterthwaite 2002)”.

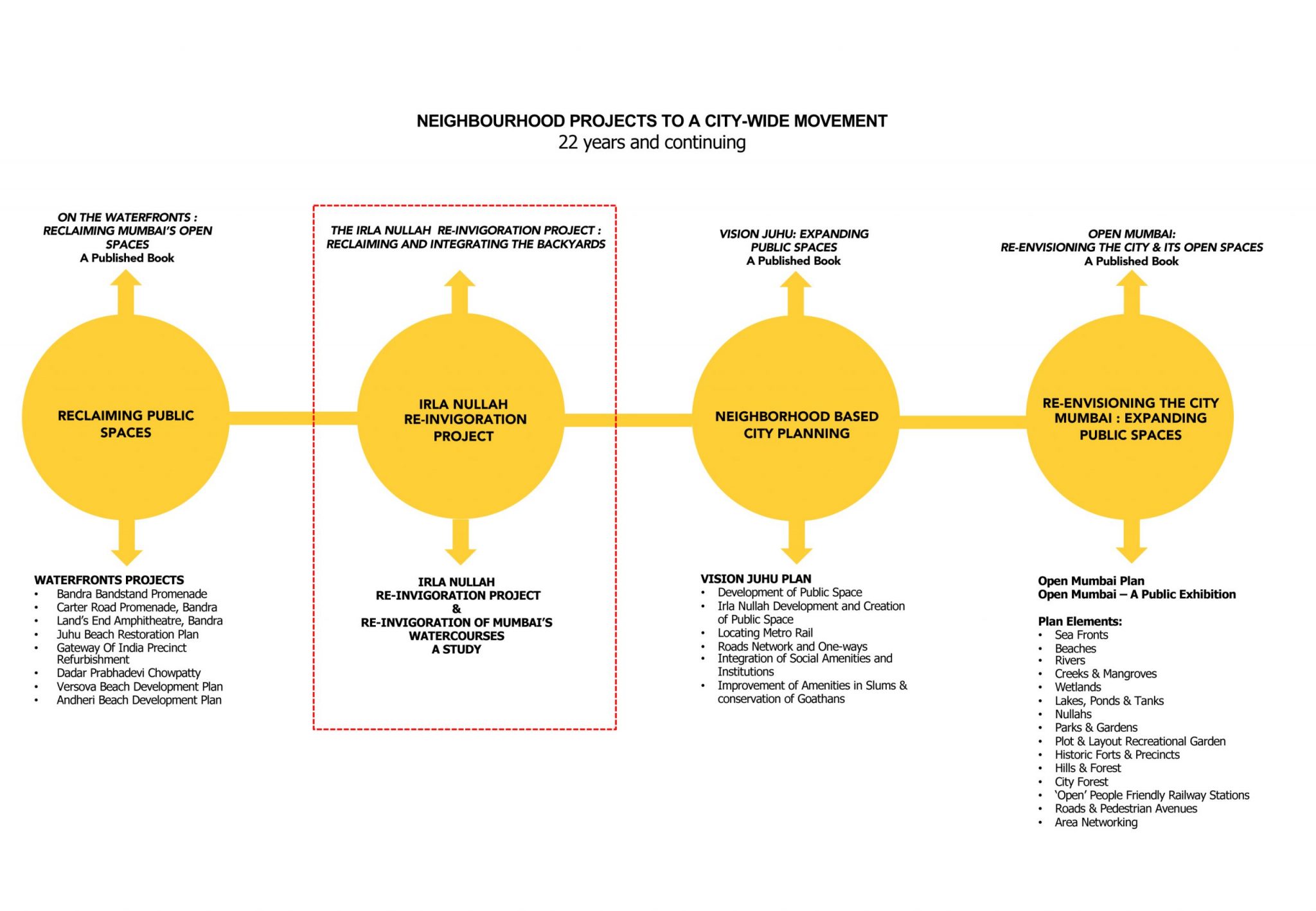

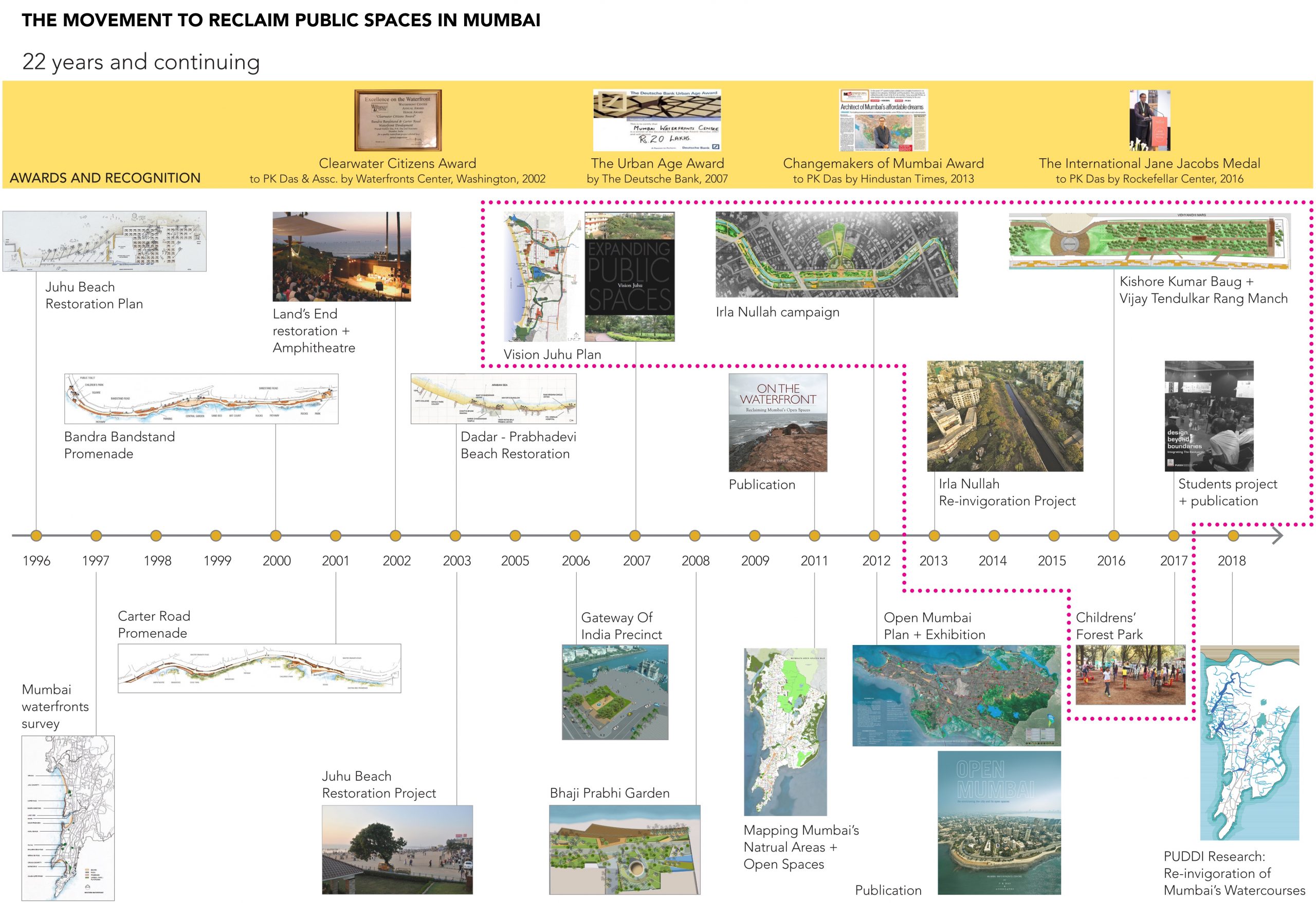

Such reconciliation is indeed the essence of the Irla movement, of which I am a part.

This phenomenon is realized in many world cities, more critically experienced in the cities of developing nations. While cities are expanding, public spaces are rapidly shrinking, in both physical and democratic terms. The democratic “space” that ensures accountability and enables dissent is also shrinking—very subtly but surely. This means space for wider public participation and dialogue are shrinking. It is in these prevailing conditions that we are compelled to pursue the idea of public spaces as being the foundation of city planning. Public spaces ensure physical, social and democratic well-being of all. The city’s shrinking open spaces are of course the most visible manifestation, as they directly and adversely affect our very quality of life.

It is in this context, I consider our struggles to pursue the idea of unification of cities through architectural and design endeavors as being important; while engaging closely with social and environmental movements. Our priority has to be to establish close relationship between architecture and people, placing strong emphasis on participatory planning from the very beginning and at every stage.

Leave a Reply