While much of the nation reacted to coronavirus by enacting either strict lockdown procedures or reckless reopening, we sought to demonstrate that it was possible to carry out in-person experiential education that was designed around strict health protocol and productivity.

Disasters, from hurricanes to wars to plagues, disproportionately impact the poor. The coronavirus pandemic, combined with this summer’s worldwide protests against police brutality and systemic racism, has laid bare and shone light upon multiple persistent societal inequalities. These inequities are notably visible and pronounced in inner city environments. Poverty, along with other social and environmental determinants of health, have left low-income and communities of color particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus. Widespread unemployment and economic uncertainty have compounded these stresses, while access to nutritious food and healthcare has only grown more limited. In the meantime, environmental, climate, and food justice issues plaguing inner-city communities continue unchecked.

In response to these challenges, Radix put out the call for and began organizing the creation of “pandemic resilience gardens”—food production centers built to not only give residents some sense of control over their futures, but to seize the opportunity in the crisis to address long-standing issues of food access and sovereignty. Similar to the victory gardens of the world wars, pandemic resilience gardens provided a sense of stability and reliability during frightening times, while simultaneously encouraging people to go outside, eat nourishing food, breather fresh air and feel sunlight—all essential for immune support. The several pallets worth of seeds we had been donated the previous fall proved enormously useful as widespread panic buying resulted in national seed shortages. This allowed us to get numerous trays of vegetable starts going in our greenhouse to be distributed to Albany residents and to neighborhood gardens. Our biggest limiting factor in planting more was a labor shortage. Working within the confines of a greenhouse, it was difficult to maintain social distancing among volunteers. Furthermore, our year-round afterschool youth program was forced largely online after schools closed. As the weather warmed, however, it was possible to move more of the planting work outside where distancing was easier and air exchanges increased.

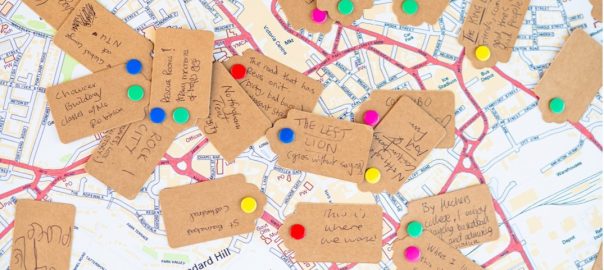

It is in this context that the Radix Center ran its “Pandemic Resilience and Climate Justice” summer program. It consisted of a ten-week in-person experiential education offering involving fifteen AmeriCorps employees (recruited through Siena College’s SPIN program) and twenty high-school age youth employed through the city’s summer youth employment program. As a team, we planted multiple garden sites, keeping them weeded and watered throughout the summer, composted significant amounts of food waste, and distributed food and vegetable starts to neighbors in need. Going beyond gardening work, students worked as teams to engage in community-based participatory research throughout the South End neighborhood, investigating socio-environmental issues including food access, evictions, lead-based soil contamination, and “innovation blocks” a door-to-door neighborhood outreach program of our partner organization, AVillage…Inc. For intellectual growth, collectively we read and studied a number of articles on topics ranging from environmental justice, food access, gender studies, prison abolition, climate change, redlining, urban commons, and more. This focused study was necessary for understanding the big picture issues and theories that informed our work in its particular context.

As their opportunities for education, employment, and entertainment have been drastically curtailed by the shutdown, urban youth have been notably impacted by the coronavirus. When schools closed in March, many of them were left in precarious positions with tenuous access to computers and reliable internet connections. At-risk youth were in danger of slipping through the cracks, cut off from meals, guidance, and other essential services provided by schools. Some youth found themselves in dangerous situations, forced into lockdown isolation with abusive family members. Far more students were simply bored, weary from zoom calls, frustrated by the lack of sports, camps, or extra-curricular opportunities of any sort. In this sense, we hoped to provide an enriching employment opportunity that gave youth the chance to be outdoors, learn, and engage with one another, albeit wearing masks and from six feet away.

Safety was of utmost importance to us in the pandemic resilience program. While much of the nation reacted to coronavirus by enacting either strict lockdown procedures or reckless reopening, we sought to demonstrate that it was possible to carry out in-person experiential education that was designed around strict health protocol. Employing program participants of co-designers of these pre-cautions, we enforced a strict stay-home-if-sick policy, mandatory mask wearing, and social distancing, all while being outdoors nearly all the time (we were blessed with remarkably good weather—on only one or two occasions was it necessary to take shelter in the neighboring warehouse, itself a well-ventilated and spacious structure). We are happy to report that to our knowledge, there were no transmissions of coronavirus within the group. In stark contrast to much of the rest of the country, infection rates in upstate New York remained relatively low throughout the summer.

The rise of Black Lives Matters and the racial justice movement over the summer of 2020 created an intense synergy with the conditions of the pandemic, and for the focus of our program. The South End of Albany is itself a prime example of what happens to a neighborhood after decades of racist policies—federal redlining practices creating zones of disinvestment where basic services are absent, substandard housing is prevalent, and opportunities for advancement are few. Just one week before its start, the South End was engulfed in protests, tear gas flooding every corner of the neighborhood. The South End precinct station, less than a block away from the Radix Center, was the epicenter for much of the protest activity, with community members demanding accountability from the local police. In response, giant concrete barricades were placed in the road by the station, blocking any vehicular access to the street. Their presence was a constant reminder of the intensity of the moment as we each day navigated wheelbarrows loaded with soil, food, and tools between their confines. The eventual removal of the blockades was a moment of jubilant celebration for the group, their symbolic shadow of oppressive securitized control lifted. While the problems facing the South End will require generations worth of work to remedy, the events of the summer created a sense of urgency and timeliness to the work of challenging degenerative structures and regenerating enviro-social equity and health.

The Black Lives Matters movement timed well with the beginning of the South End Night Market, a weekly outdoor market organized by AVillage…Inc. that featured local, predominantly black vendors selling a variety of products to the local community in an effort to build local black wealth and prosperity. After the initial shutdown, the future of the market was cast in doubt as there was a ban on gatherings of almost any sort. Fortunately, Radix’s agricultural “essential” designation came in useful once again as it permitted farmers markets to continue. By selling our locally grown produce at the Night Market, it could be regarded as a farmers market and be allowed to continue. Vendors were carefully spaced on the sidewalk outside of Radix with tape marking the safe setbacks for shoppers to stand behind. The Night Market drew progressively larger crowds over the summer, creating a community event where local wares and affordable produce could be bought. We were fortunate to involve Pandemic Resilience participants in the market, having them help with tasks ranging from set up, produce sales, vendor questionnaires and promotions.

As the summer ends, autumn brings cooler temperatures and continuing uncertainty. How long will this state of emergency continue for? Will in-person education ever resume? Are further waves of disease and political violence on the horizon? While there are no clear answers, we know that we must increase our adaptive capacity to effectively respond to future events with the needed urgency. It may be entirely possible that summer 2021 is a replay of summer 2020, but if it is, we at least have some blueprint of success to work from.

Scott Kellogg

Albany

Leave a Reply