Citizenship is derived from city, and floristry from forest or jungle. Forest and human being live a socio-ecological pact in which the forest becomes a new citizen respected in its integrity, stability, and extraordinary beauty. Both benefits, as the utilitarian logic of exploitation is abandoned and the logic of mutuality is assumed, which implies mutual respect and synergy. — Leonardo Boff[1]

2020 has been a year full of uncertainties for the whole world. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to change our perception in many aspects of daily life.

This work is long and has not been easy. Sometimes we are discouraged by lack of resources and understanding, by violence, by increases in poverty, by politics, by the realities of Colombia. But our hope is still alive, and we remain motivated to contribute our little piece of peace to the life of this beloved corner of the hills of Bogota.

The country’s capital is a privileged city, as it is surrounded by a majestic mountain range, a set of moorlands[3], peaks, and multiple watercourses that have unfortunately been barely accessible to its inhabitants.

This low access is a subject of reflection and action for those of us who are part of the Bogota Hills Foundation (Fundación Cerros de Bogotá) and for the various groups formed for the defence and the informed and sustainable use of the hills. We assume ourselves as citizens in the high plain tropical forest in the region of Bogota. We extend this type of citizenship “inter-retro-connected” in a new civilizing narrative. In an area of transition between the city and the forest reserve, we promote ways of relating to others and nature in an urban-rural peace process within a city of more than eight million inhabitants, and in a country that is still trying to understand what this means on a national scale. That is why we are agents of peace.

Quarantine does not stop life in the hills

During this year, which has been full of uncertainties, intimacies revealed in virtual meetings, and work with people who only know each other through a screen, the strength and passion of a group of florestanios (“citizens of the forest”) added to the fears derived from the scarcity of opportunities or resources and generated a challenge of creation and intense movement.

The quarantine, which has just been lifted in Bogotá after six long months, shows the impact that the pandemic has had on the streets, on businesses, and on meeting places. We can now see the citizens, almost hidden behind their masks, walking at a different pace of life.

Despite this landscape, life buzzes in the Eastern Hills. Nourished soils and others in the process of regeneration, species of fauna and flora as well as the bodies of water that surround it give life to the city, clean the air, provide a sense of well-being, and reaffirm the sense of belonging.

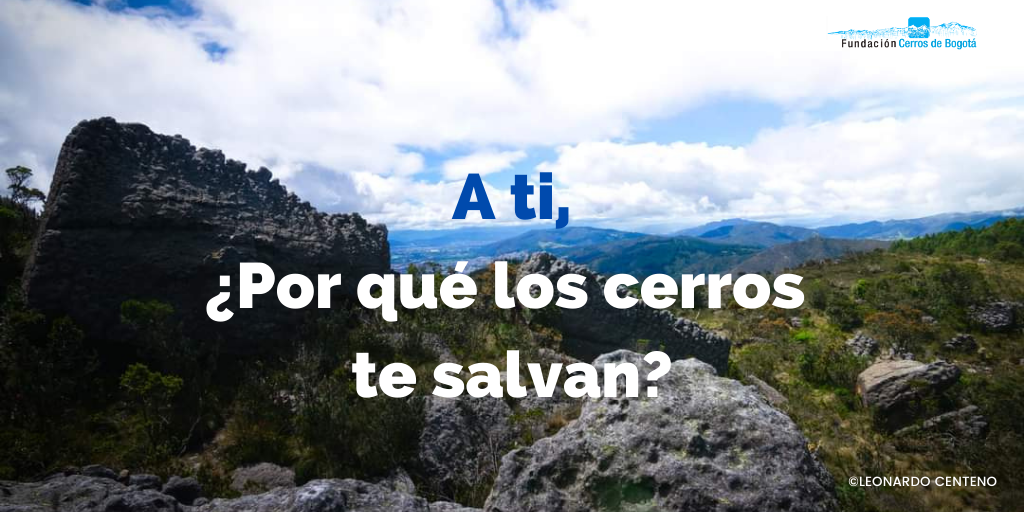

Apart from the importance of their very existence, the hills are also subjects of reinvention. Coinciding with our 11th birthday, as Bogota Hills Foundation, we decided to launch the campaign: The Hills Save Us to highlight the vital and protective role of the hills for the city and reiterate the importance of complying with the ruling of the Council of State that ordered the creation of a social, ecological, and recreational corridor. A need that became more evident in these times of pandemic and quarantine. #LosCerrosNosInspiran (#TheHillsInspireUs) #VozCerros (#HillsVoice) #VisionCerros (#HillsVission) #LosCerrosNosSalvan (#TheHillsSaveUs).

During these six months, we worked intensely to launch the largest platform with complete information about the Eastern Hills, its people, its flora, its fauna, its moors, and its water basins. In addition, citizen initiatives, projects undertaken with children, footpaths, historical studies, and neighbourhood histories are shown there. The citizens will be able to take the hills home thanks to the drawings we designed to download and colour, and, in the process, learn names, toponyms, and sacred places.

A socio-ecological project that cannot be postponed

As “florestines” citizens, we have witnessed the changes that have altered the ecosystem of our hills, and, perhaps pretentiously, we have always said that the mountain needs us for its restoration. We make plans and talk about how necessary these actions are to recover the biodiversity lost by the construction of the city. But at this historic moment, after having spent six months in quarantine, we have seen from our windows the wonderful chain of life. We have breathed the fresh air; we have rediscovered the landscape and only now do we realize that it is not we who will save the hills, but they are the ones who can save us.

In light of the current crisis, the need for green spaces in urban environments – for us and for the whole world – has become clear and precise. People from different latitudes found there a source of strength to face the crisis. However, in other cities, perhaps in too many, the deficiency of safe and accessible green spaces that affect the improvement of the physical and mental health of the communities became evident.

To corroborate this statement, it is interesting to mention a survey carried out by Greenpeace Colombia, as a result of the isolation, in which it was found that 41% of the people interviewed currently value public green spaces more and consider it important to expand, take care of and protect them for the good of the people and the communities, in addition to promoting their sustainable use. Likewise, according to what was observed by the Bogota Hills Foundation at this time, the pressure from citizens to walk the trails, even at the risk of safety, shows the acute need for natural spaces without congestion.

It is precisely this scenario that has motivated us to insist on the possibility of building a shared vision and comprehensive management for the city’s eastern hills. The Foundation dreams of creating a socio-ecological corridor in the Adjustment Strip that restores existing trails with native species and integrates new public spaces. The dream also involves neighbours and hill leaders in the care and management of this new urban ecosystem (what the Foundation calls neighbourhood pacts). The neighbourhood pacts will be trained guides and share stories about ethnobotany, geology, and environmental history at lookouts, among native species as cedars, tibars, tunos, and amargos[4], through visible and clean streams, while spotting Andean guans, hummingbirds, weasels, and frogs.

This affectionate and productive coexistence of the citizen with the imposing Eastern Hills, utopian or risky for some, is already becoming a reality through a small living laboratory in the three hectares of the Civil Society Natural Reserve called Cultural Threshold Horizons. There, with the collaboration of volunteers and experts, talks, collaborative restoration with native species, orchards, and composting processes have been carried out, forming a pilot project that can be replicated as private property for public use.

The Natural Reserve acts as a laboratory of collaborative transformation and, through a volunteer program, we have been carrying out participative restoration for five years now (730 plants of more than 33 different species)[5]. We also generate collective works such as the creation of barriers and filters to retain plant material, mitigating the impact of rain on the area; we produce land art, and offer weekly talks on urban ecology called Cátedra Cerros Bogotá (Bogota Hills Chair) in which the mountain takes the stage.

This work is long and has not been easy. Sometimes we meet walkers who do not fully understand our work. We are discouraged by the lack of resources or frustrated by the slow progress of our activities. We are also overwhelmed by the reality we live in our country, the violence, the attacks on environmental leaders, the increase in poverty, and the generalised pain of a country that resists change, even though it tries hard. We are sometimes saddened by the lack of will and political action to restore the Eastern Hills to its role within the community. However, our hope is still alive, and we remain motivated to contribute our little piece of peace to the life of this beloved corner of the hills of Bogota[6].

Diana Wiesner

Bogotá

Translated by Elizabeth Barragan Porras

Notes:

[1]Boff, Leonardo. “Florestanía” in FLORÆ Magazine # 1. Bogotá: Flora ars+natura, August 2015.

[2]The hills shelter 91,444 inhabitants (2018) distributed in 64 neighbourhoods between the localities of Usme, San Cristóbal, Santa Fe, Chapinero, and Usaquén.

[3] https://cerrosdebogota.org/index.php/nuestros-paramos/

[4] Native trees species common names

[5]According to records published in the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)

https://www.gbif.org/, the Bogota’s Eastern Forest Protection Reserve, as of August 2020, has 1673 species of flora and fauna, of which 137 are endemic, that is, their geographical distribution is limited to this area.

[6] This article is a tribute to that passionate group that has accompanied me this year and whom I thank from the heart to continue increasing the population of “florestanios”: Maria A. Mejía, Lucía Martínez, Isabela Uribe, Jorman Romero, Gabriela Fernández, Miguel Leguízamo, María Paula Guerrero, Nicolás Bazzani, Adriana Cabrera, Mateo Hernández, Ricardo Gamboa, Francisco González, Martha Gómez, Santiago Rosado, Leonardo Centeno, Fernando Cruz, Carlos Lince, Mateo Hernández, Leonardo Villa, Lina Prieto, Jaime A. Vargas, filmico. col, Laura Gómez, Elsa Rey, Carolina Fiallo, Ingrid Obando, Juan Camilo Cruz, Byron Calvachi, Johanna González, Lina Prieto, Andrés Gómez, Juan Camilo Castro, Sebastián Cerquera, María Alejandra Peña, Ana Puerto, Luisa Castro, Juan Pablo Rojas, Nicolás Barrero, Jacqueline Vargas, Erika Tovar, Sofía Estrada, Mark Skepasts, Elizabeth Barragán, Ivone Malaver, Nathaly Ortiz, Gabriela Fernandez and Lauryin García.

* * *

Los cerros nos salvan

Ciudadanía se deriva de ciudad, y florestanía de floresta o selva. Floresta y ser humano viven un pacto socioecológico en el que la floresta pasa a ser un nuevo ciudadano respetado en su integridad, estabilidad y extraordinaria belleza. Ambos se benefician, pues se abandona la lógica utilitarista de la explotación y se asume la lógica de la mutualidad, que implica respeto mutuo y sinergia. —Leonardo Boff[i]

2020 ha sido un año lleno de incertidumbres para el mundo entero. La pandemia derivada de la enfermedad denominada covid-19 nos ha obligado a cambiar nuestra percepción en muchos aspectos de la vida cotidiana.

Este trabajo es largo y no ha sido fácil. A veces nos desalienta la falta de recursos y comprensión, la violencia, el aumento de la pobreza, la política, las realidades de Colombia. Pero nuestra esperanza sigue viva, y seguimos motivados para contribuir con nuestro pequeño trozo de paz a la vida de este querido rincón de las colinas de Bogotá.

La capital del país es una ciudad privilegiada, ya que está rodeada por una cadena montañosa majestuosa, un conjunto de páramos, picos y múltiples cauces de agua que han sido, infortunadamente, poco accesibles para sus habitantes.

Ese bajo acceso es un tema de reflexión y de acción para quienes hacemos parte de la Fundación Cerros de Bogotá y para los diversos grupos conformados para la defensa y el uso informado y sostenible de los cerros. Nos asumimos como ciudadanía en la floresta tropical de altiplano, en la región de Bogotá. Ampliamos esta forma de ciudadanía «interretroconectados» en una nueva narrativa civilizatoria. En un área de transición entre la ciudad y la reserva forestal promovemos formas de relacionarnos con los otros y con la naturaleza en un proceso de paz urbano-rural dentro de una ciudad de más de ocho millones de habitantes, en un país que aún trata de comprender lo que esto significa a escala nacional. Por ello, somos agentes de paz.

La cuarentena no detiene la vida de los cerros

Durante este año, que ha estado lleno de incertidumbres, de intimidades reveladas en reuniones virtuales y de trabajos con personas que solo se conocen a través de una pantalla, la fuerza y la pasión de un grupo de «florestanios», sumadas a los miedos derivados de la escasez de oportunidades o de recursos nos generó un desafío de creación y de movimiento intenso.

La cuarentena, que recién se levanta en Bogotá, después de seis largos meses, permite constatar el impacto que la pandemia provocó en las calles, en los negocios, en los escenarios de encuentro. Podemos apreciar ahora a los ciudadanos, casi escondidos detrás de sus mascarillas, caminando a un ritmo de vida diferente.

A pesar de este paisaje, la vida bulle en los Cerros Orientales, suelos nutridos y otros en proceso de regeneración, especies de fauna y flora así como los cuerpos de agua que la rodean dan vida a la ciudad, limpian el aire, brindan una sensación de bienestar y reafirman el sentido de pertenencia.

Aparte de la importancia de su misma existencia, los cerros también son sujetos de reinvención. Coincidiendo con nuestro 11.º cumpleaños, como Fundación Cerros de Bogotá decidimos lanzar la campaña: Los cerros nos salvan, a fin de resaltar el papel vital y protector de los cerros para la ciudad y reiterar la importancia de cumplir el fallo del Consejo de Estado que ordenó la creación de un corredor social, ecológico y recreativo, una necesidad que se hizo más evidente en estos tiempos de pandemia y de cuarentena. #LosCerrosNosInspiran #VozCerros #VisionCerros #LosCerrosNosSalvan

En estos seis meses trabajamos con intensidad para lanzar la mayor plataforma con información completa sobre los Cerros Orientales, su gente, su flora, su fauna, sus páramos, sus cuencas hídricas; además, se muestran allí iniciativas ciudadanas, proyectos emprendidos con niños, senderos, estudios históricos e historias de barrios (https://cerrosdebogota.org/). Los ciudadanos podrán llevar los cerros a su casa gracias a los dibujos que diseñamos para descargarlos y colorearlos, y de paso aprender nombres, toponimias, lugares sagrados.

Un proyecto socioecológico impostergable

Como ciudadanos «florestanios» hemos presenciado los cambios que han alterado el ecosistema de nuestros cerros, y, tal vez pretenciosamente, siempre hemos dicho que la montaña nos necesita para restaurarla. Se hacen planes y se habla de lo necesarias que son estas acciones para recuperar la biodiversidad perdida por la construcción de la ciudad. Pero en este momento histórico, luego de haber pasado seis meses en cuarentena, hemos visto desde nuestras ventanas la maravillosa cadena de vida, hemos respirado el aire fresco, hemos redescubierto el paisaje y recién ahora nos damos cuenta de que no somos nosotros quienes salvaremos a los cerros sino que son ellos los que nos pueden salvar.

A la luz de la actual crisis, la necesidad de los espacios verdes en los entornos urbanos —nuestros y de todo el mundo— se ha vuelto clara y precisa. Habitantes de distintas latitudes encontraron allí una fuente de fortaleza para enfrentar la crisis; sin embargo, en otras ciudades, tal vez en demasiadas, se hizo evidente la deficiencia de espacios verdes seguros y accesibles que inciden en el mejoramiento de la salud física y mental de las comunidades.

Para corroborar esta afirmación, es interesante mencionar una encuesta que realizó Greenpeace Colombia, a raíz del aislamiento, en la que se encontró que un 41 % de los interrogados valora en este momento más los espacios públicos verdes y considera importante ampliarlos, cuidarlos y protegerlos para el bien de las personas y de las comunidades, además de promover un uso sostenible de los mismos. Así mismo, según lo observado por la Fundación Cerros de Bogotá en esta época, la presión de los ciudadanos por recorrer los senderos, inclusive corriendo riesgos de seguridad, evidencia la necesidad acusiosa de contar con espacios naturales y sin congestiones.

Es justamente este escenario el que nos ha motivado a insistir en la posibilidad de construir una visión compartida y una gerencia integral para los Cerros Orientales de la ciudad. La Fundación sueña con la creación de un corredor socioecológico en la Franja de Adecuación que restaure a su paso los senderos existentes con especies nativas e integre nuevos espacios públicos. El sueño también involucra a los vecinos y líderes de los cerros en el cuidado y manejo de este nuevo ecosistema urbano (lo que la Fundación llama pactos de vecindad), quienes serán guías capacitados y compartirán relatos sobre etnobotánica, geología e historia ambiental en miradores, entre cedros, tíbares, tunos y amargosos, a través de quebradas visibles y limpias, avistando al tiempo pavas de monte, colibríes, comadrejas y ranas.

Esa convivencia afectuosa y fructífera del ciudadano con los imponentes Cerros Orientales, utópica o riesgosa para algunos, ya viene haciéndose realidad mediante un pequeño laboratorio vivo en las tres hectáreas de la Reserva Natural de la Sociedad Civil denominada Umbral Cultural Horizontes. Allí, con la colaboración de voluntarios y expertos, se han llevado a cabo charlas, restauración colaborativa con especies nativas, huertas y compostaje, conformando un proyecto piloto replicable como predio privado de uso público.

La Reserva Natural actúa como un laboratorio de transformación colaborativa y mediante un voluntariado llevamos ya cinco años de restauración participativa (730 plantas de más de 33 especies diferentes)[iii]; generamos, además, obras colectivas como la creación de barreras y filtros para retener material vegetal, mitigando así el impacto de las lluvias sobre la zona; producimos obras de arte de la tierra (LandArt), y ofrecemos charlas semanales sobre ecología urbana denominadas Cátedra Cerros Bogotá en las que la montaña se toma la palabra.

Este trabajo es largo y no ha sido fácil. A veces nos encontramos con caminantes que no comprenden bien nuestra labor, pasamos sinsabores por la falta de recursos o nos frustra el bajo eco que a veces tienen nuestras actividades. También nos apabulla la realidad que vivimos en nuestro país, la violencia, los atentados contra líderes ambientales, el incremento de la pobreza y del dolor generalizado por un país que se resiste a cambiar, aunque lo intenta con fuerza. Nos genera tristeza a veces la falta de voluntad y de acciones políticas que le devuelvan a los Cerros Orientales su papel dentro de la comunidad. Sin embargo, nuestra esperanza sigue viva y seguimos motivados por contribuir con nuestro pedacito de paz a la vida de este rincón amado que son los cerros de Bogotá.[iv]

Diana Wiesner

Bogotá

Traducido por Elizabeth Barragan Porras

Sobre The Nature of Cities

Notas:

[i] Boff, Leonardo. «Florestanía» en Revista FLORÆ # 1. Bogotá: Flora ars+natura, agosto de 2015.

[ii] Los cerros albergan 91 444 habitantes (2018) distribuidos en 64 barrios entre las localidades de Usme, San Cristóbal, Santa Fe, Chapinero y Usaquén.

[iii] Según los registros publicados en la Infraestructura Mundial de Información en Biodiversidad (GBIF)

https://www.gbif.org/, la Reserva Forestal Protectora Bosque Oriental de Bogotá, a corte de agosto de 2020, cuenta con 1673 especies de flora y fauna, de las cuales 137 son endémicas, es decir, su distribución geográfica está limitada a esta área.

[iv] Este artículo es un homenaje a ese grupo apasionado que me ha acompañado este año y a quienes agradezco de corazón seguir adelante aumentando la población de «florestanios»: María A. Mejía, Lucía Martínez, Isabela Uribe, Jorman Romero, Gabriela Fernández, Miguel Leguízamo, María Paula Guerrero, María Elvira Talero, Nicolás Bazzani, Adriana Cabrera, Mateo Hernández, Ricardo Gamboa, Francisco González, Martha Gómez, Santiago Rosado, Leonardo Centeno, Fernando Cruz, Carlos Lince, Mateo Hernández, Leonardo Villa, Lina Prieto, Jaime A. Vargas, Laura Gómez, Elsa Rey, Carolina Fiallo, Ingrid Obando, Juan Camilo Cruz, Byron Calvachi, Johanna González, Lina Prieto, Andrés Gómez, Juan Camilo Castro, Sebastián Cerquera, María Alejandra Peña, Ana Puerto, Luisa Castro, Juan Pablo Rojas, Nicolás Barrero, Jacqueline Vargas, Erika Tovar, Sofía Estrada, Mark Skepasts, Erika Barragán, Ivone Malaver, Nathaly Ortiz, Elizabeth Barragan,Gabriela Fernandez, Maria Jose Velasco y Lauryin García.

Leave a Reply