We might know how green spaces benefit our health, and we might even know which green spaces are best for us, but what is less clear is how to get people to engage with these green spaces.

How can we design urban green spaces that support health and well-being? What are the roles played by users, practitioners, and researchers? These questions guided our virtual seed session “Designing urban green spaces for health and well-being” during the TNOC Festival 2022. Fifteen participants shared their experience as a user of green space, a landscape designer (practitioner), or as a researcher. This approach allowed us to generate actor-targeted recommendations for designing green and healthy cities.

Before presenting the harvest of our seed session, we should share something about how this seed session came to be. Agnès Patuano and Marthe Derkzen co-lead the Health and Environment Cluster of Wageningen University & Research and were looking for a collaborative opportunity to discuss the health promotion features of urban nature landscapes. The Nature of Cities Festival 2022 offered a platform to bring together not only researchers but also practitioners, artists, users, and policymakers. And, importantly, it was possible to build on a previous TNOC blog post by Takemi Sugiyama and others on ‘Nature Fix for Healthy Cities: What Planners and Designers Need to Know for Planning Urban Nature with Health-benefits in Mind’, which was published after organizing a similar seed session at the 2021 edition of the Festival. The key messages in that blog post were primarily addressed to planners and designers of Australian cities. In the present blog post, we propose and discuss recommendations for a global and diverse audience including green space users and researchers along with designers. These recommendations are based on discussions between participants from the Americas, Africa, Australia, and Europe.

What makes a healthy city?

As a pre-session exercise, we asked participants: what do you think makes a healthy city? We collected their answers and generated a word cloud (see below) that reflects their image of a healthy city. Spaces that are green, natural, and blue (water) pop up as important features of a healthy city. The way in which a city’s infrastructure is designed also clearly influences its health potential, e.g., through accessibility, pedestrian-friendliness, and opportunities for active mobility. Finally, human elements such as a sense of community, art, and care are seen as aspects of a healthy city.

Three perspectives on green spaces emerge: the users, the practitioners, and the researchers. This is developed hereafter.

From the perspective of researchers:

Researchers are well aware of the health benefits of urban green spaces. Studies have found that having urban green spaces nearby can confer many health benefits, which are derived from multiple pathways. An overview of these benefits can be found in the 2016 WHO review of evidence. For instance, urban green spaces can facilitate people’s physical activity, which is considered a “wonder drug”. Contact with nature (physical and visual exposure to green elements) has been shown to be beneficial to mental health. Promoting opportunities for social interaction is another mechanism through which urban green spaces can contribute to nearby residents’ health. Those spaces may be public, as in equally accessible to all citizens, or “semi-public” such as in the urban green commons (Colding and Barthel, 2013) for which diverse control and managing rights may be given to a community. In either case, urban green spaces are an important resource for community health.

However, it is also known that green spaces are not evenly distributed, and their quality also differs between areas. It has been suggested that disparities in the access to and quality of urban green spaces may be contributing to socioeconomic inequalities in health since disadvantaged areas tend to have poor-quality parks (Barthel et al., 2021). Even more critically, access to green space has been found to be associated with reducing the difference in health observed between the richer and poorer (by up to 40%) (Mitchell et al., 2015). Regarding green spaces where social interaction is naturally occurring, such as the urban green commons, access, and maintenance are precisely the object of numerous claims by communities that feel left out of modern urban developments: famous examples are “guerrilla gardening” in New York (Camps-Calvet et al., 2015) and the protests against the destruction of Gezi Park in Istanbul (Kuymulu, 2013).

Since improving the health of the entire population by eliminating uneven distribution of poor health is a key challenge for public health, it is important to make sure that environmental initiatives to improve health pay attention to the disparities between advantaged and disadvantaged areas. In this case, improving all green spaces equally would not narrow the health gap. What is needed is to identify target areas in which improving green spaces can help mitigate health inequalities. Such a target approach requires collaboration between researchers, public sectors (local government), and local communities. Researchers can provide information about areas where residents can benefit most from green space enhancement. Local government and the community work together to identify how best to enhance green spaces to meet the needs of the community. Researchers can contribute to this process by helping them to make evidence-based decisions.

In this process, it is critical to involve local communities to assess their needs. Improving green spaces has been shown to lead to gentrification in some instances (Wolch, Byrne & Newell, 2014). By taking residents’ needs into account, targeted interventions can be planned which can lead to health benefits for them without driving housing prices up and avoiding the displacing effect. However, communities can be difficult to engage as they lack disposable time and possibly also interest to participate in planning and designing processes. Therefore, a better understanding of the community is needed, i.e., time availability, care responsibilities, age, income, gender differences, digital gaps, etc., as well as their potential involvement as active decision-makers in the solutions to their needs and expectations. In our seed session, researchers shared their experiences and recommendations to ensure participation, proposing activities and tools to involve participants. The guiding question was: How can vulnerable populations be involved in green space research?

Recommendations to involve vulnerable populations in research:

- Engage with the community in a way to gain their trust and better understand the community vision and its habits.

- Apply non-invasive methods, such as (participant) observation, or methods that can be of use to participants, such as focus groups, which can strengthen community ties and offer opportunities for learning. Practicalities: Split the participants into smaller groups if needed.

- Explore alternative tools to involve people, such as gamification, digital tools and apps, and collaborative art installations. Practicalities: Take care of the digital gap!

- Use communication methods in the right places, such as posters and flyers in community centers, and through the right persons, such as community gatekeepers. Practicalities: Carefully consider how you communicate and where.

- Make sure you communicate with the municipality to join forces and limit participant burden.

- Carefully consider the timing of participant involvement in your research process. Do you want to involve the community at the start, or throughout via living labs and other co-creation processes? Practicalities: Be wary of what expectations you might raise.

- Make sure the outcomes of your research bring something directly valuable to the community, as this is part of reciprocity on which trust depends. Practicalities: Communicate your research according to your audience.

- Last but not least, your attitude as a researcher is key: be humble, culturally sensitive, and mindful of the context and local perceptions of “green needs” and wishes. We need to pay more attention to what ‘green’ means, what ‘vulnerable’ means, and the intersectionality of both.

From the perspective of practitioners:

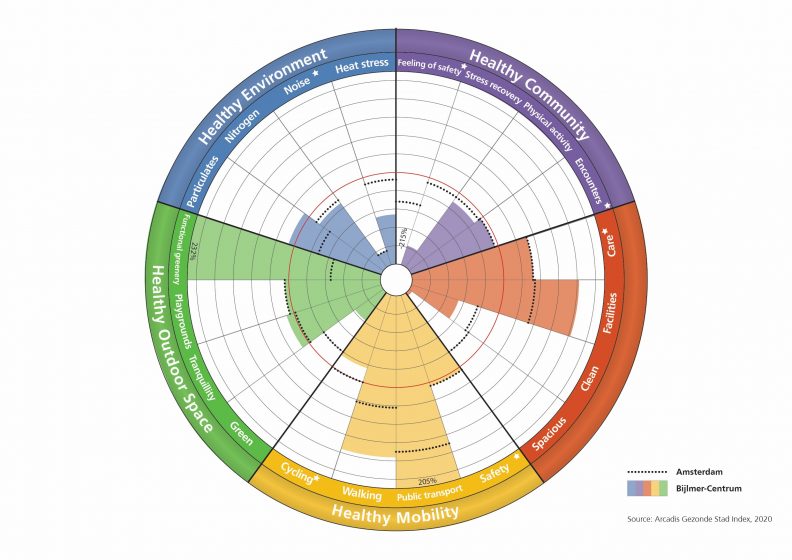

A perspective that is not often taken into consideration within academic research is that of practitioners. Particularly, within landscape architecture, there is a considerable gap between theory and practice that remains to be bridged. In order to invite practitioners’ voices into our seed session, we enlisted the help of John Boon, a senior landscape architect in the Dutch office of Arcadis, an international design and engineering bureau. In 2020, Arcadis conducted their own research, based on research of the RIVM (the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment in the Netherlands), and developed the Healthy City Index, an assessment of the health conditions provided by the environment in Dutch cities. Therefore, John was invited to the seed session in order to lead a discussion for practitioners on:

How do you include health considerations in your design?

Unfortunately, though perhaps characteristically, no other landscape architect or urbanism or spatial planning practitioner was in attendance to share their experience and recommendations. Therefore, we share here only John’s recommendations from his own practice. Specifically, using the indicators from the Healthy City index, landscape architects at Arcadis were able to assess the health threats and opportunities present in specific sites in order to target their interventions.

These indicators include:

- A healthy environment, including air quality, less noise disturbance, and low heat stress

- A healthy community, meaning a city where people feel safe, where they can manage their stress, where being physically active is attractive, and with plenty of meeting places in public spaces.

- A healthy built environment, meaning not too dense, clean, and with facilities accessible and usable by everyone

- Healthy mobility, where it is safe and easy to move around by bicycle or on foot, and with good public transport

- Healthy outdoors, including green spaces to play in or look at, with quiet, sheltered places (from the noise, and the wind), and where children can play outside.

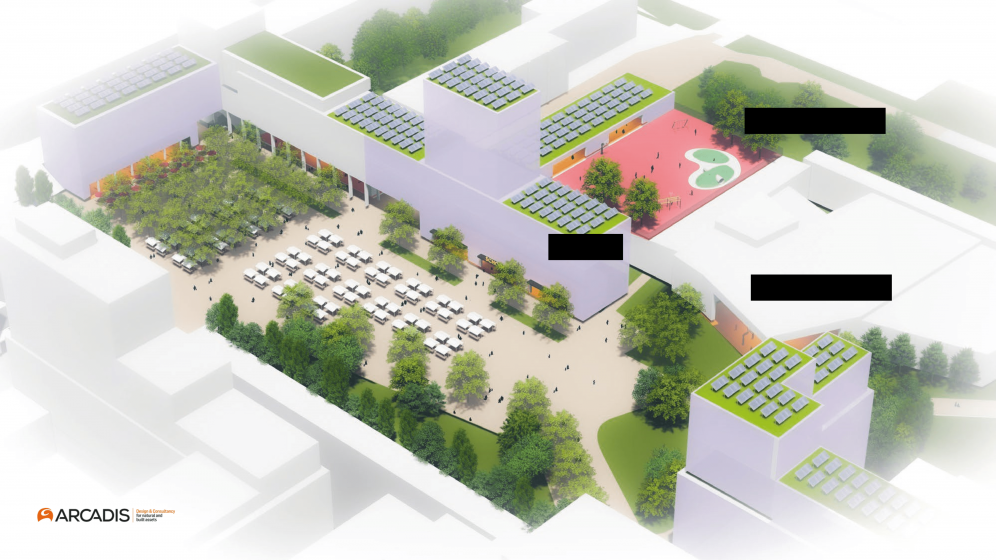

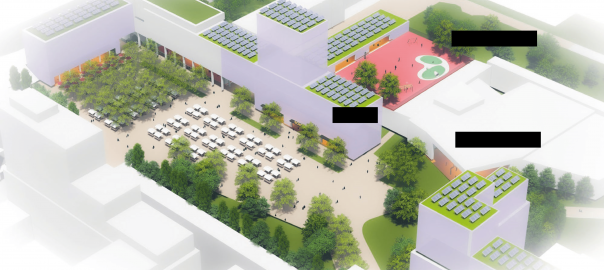

In his presentation, John Boon shared an example of such an intervention with the case of Amsterdamse Poort, a vulnerable district of Amsterdam.

First, using open data and GIS, they analyzed the situation in the area and compared it with Amsterdam as a whole and the other 19 cities in the Healthy City Index. Using these indicators, they found out the elements of the environment which needed improving: residents needed more green spaces, less pavement, and more opportunities to meet and exercise.

Therefore, the designers chose to reduce the number of paved surfaces and to add greenery to provide a healthy and attractive public space also visible from the residents’ homes. They stimulated physical activity by making the walking routes more attractive and by adding facilities such as sports fields and a climbing wall. And they placed outdoor seating so meeting people was facilitated.

Credit: ARCADIS

Credit: ARCADIS

You can read more about the design of Amsterdamse Poort here (in Dutch).

Recommendations:

From this example, it is clear that the Healthy City Index can easily be used by practitioners in the Netherlands but also in other areas of the world where similar data might be available, as a starting point for design interventions. However, beyond GIS and open data, it is always best to also involve the residents themselves. In cases where public participation needs to be organized by the designer, other recommendations were formulated through the discussion:

- Communicate with residents to let them know what is on offer

- Be open to diverse interests

- Also, talk with users about functions and programming, and not only about design

- Put forward short-term achievements to motivate the community!

- You can raise expectations about what environment can be created, but make sure you can deliver.

- Take care to include communities also after a green space has been implemented. A flourishing green space needs physical but also social maintenance.

From the perspective of green space users:

To address the user perspective, we tackled the question: How to organize civic participation in urban green spaces? Marthe Derkzen introduced the topic by sharing examples from the research project PARTIGAN at Wageningen University & Research, which is about participatory greening as a strategy to reduce socioeconomic health disparities. She illustrated how green citizen initiatives can provide well-being benefits to people working and volunteering at these shared spaces. Green citizen initiatives are designed and led by citizens and have a clear local and bottom-up character. Think of a community garden, food forest, or veggie patch in a residential neighborhood where people collaboratively work, often as volunteers.

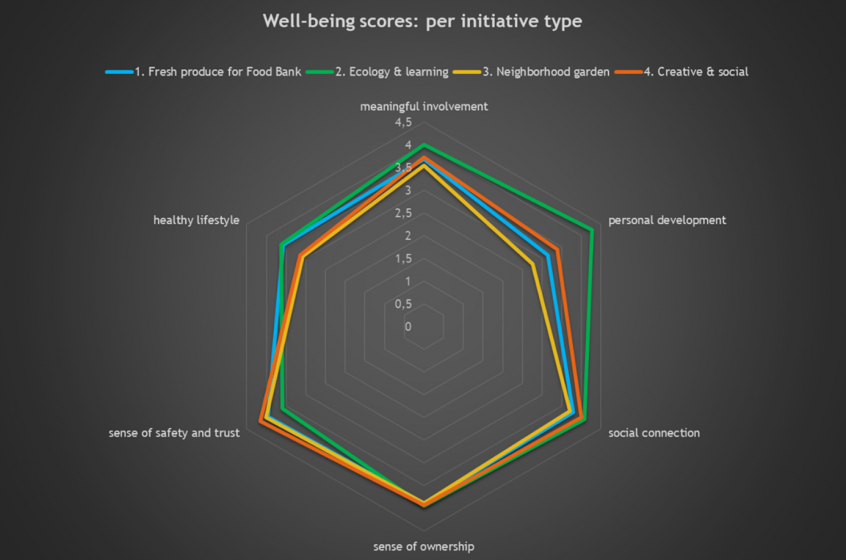

The PARTIGAN project includes four types of green citizen initiatives (see image): an urban agriculture initiative with close to 100 volunteers that produce mainly for the food bank, medium-sized initiatives that focus on ecological values and knowledge sharing or horticultural training, small community gardens that are first of all social meeting places for the neighborhood, and broader initiatives that feature a garden next to other activities such as creative workshops, yoga, or theater classes.

So, how do these user-designed urban green spaces contribute to health and well-being? We conducted interviews, a survey, and Photovoice experiment (see the TNOC essay Growing food together is healthy) to explore the well-being benefits of the aforementioned green citizen initiatives. Well-being outcomes were assessed on six dimensions, as is visible in the spider diagram. The initiatives score highest on the sense of ownership, sense of safety and trust, and social connection, while the experienced personal development varies among the different types of initiatives. This indicates that the way an initiative is developed and coordinated influences the type of effect it has on volunteers’ well-being. For more details on the study, please see the journal article Healthy urban neighborhoods by Derkzen et al. (2021).

Credit: Marthe Derkzen

The participants in the Festival session shared their own examples of how users get involved in local green spaces. Commonly mentioned examples were community gardens where vegetables are being grown by active neighbors and volunteers. An example from the Netherlands was BuitenLeeft, an outdoor meeting spot where everything is about the relationship between people and nature. In the UK, there are plans to develop an old railway line as a green walking/cycling route. The additional value of such projects is the possibility to connect urban nature with peripheral nature areas. Another UK example is the community street audits, which made us wonder whether one could organize community park audits as well, to evaluate park quality by users. Regarding health, one participant mentioned that many organizations now have sustainability goals (often connected to the UN SDGs) and that health is part of these goals, which could help to discuss this with clients when designing urban green space.

Recommendations for user involvement

When discussing the user perspective on designing urban green spaces for health, the conversation quickly came to revolve around the question ‘How to organize civic participation in urban green spaces?’ Several recommendations were formulated on this topic:

- Split the community into smaller task groups, so that people can contribute according to their interests, and feel ownership and responsibility

- Propose activities and events, or better: have people themselves organize green activities

- Social media groups work well for self-organization

- Use green space as a stepping stone for other activities and user groups, e.g. start with a community garden and over time reach out to artists to involve children and youth

Finally, we talked about the mode of communication, and especially about the perks of online tools. During the pandemic, we have learned that online participation makes it easier for some target groups (for example younger people) to participate. A tool used by Arcadis is Swipe-o-cratie. This is a Dutch app through which users can judge a design option on their mobile phone. They ‘swipe’ the example to the ‘good’ or ‘bad’ side, just like on Tinder. This facilitates obtaining user input in a low-key manner.

However, our discussion ended with what you could call a small warning regarding the exclusive use of online tools. The efficiency of exchanging short online messages in collaborative processes, and the difficulty to engage all potential actors, remain challenges (Deng et al., 2015; Rao, 2013). Such tools may still be perceived as elitist or exclusionary by more vulnerable communities. The shallow sense of engagement online tools provide often requires the community to additionally meet offline. Indeed, a network already connected by personal ties and trust has more chances to overcome the possible digital limitations.

We therefore really need to use both online and offline communication when engaging with users, as we should not forget about the conviviality and quality of offline exchanges!

Wrap-up

Although the aim of the session was originally to discuss three different perspectives on the design of urban green spaces for health and well-being, it is clear from the recommendations above that the main concerns of our participants revolved around the participation of vulnerable populations, who could benefit greatly from green space improvement. When considering the significant amount of evidence for the health benefits of urban green spaces, this is not surprising. We might know how green spaces benefit our health, and we might even know which green spaces are best for us (Beute, et al., 2020), but what is less clear is how to get people to engage with these green spaces.

Urban green spaces are inherently social spaces, connecting communities and facilitating engagement. They are also relatively easy to change compared to other urban infrastructures and deliver quick wins. At the same time, cities have to deal with increasing land scarcity. One place where this is reflected is in the gardens of newly built homes – these are becoming smaller and smaller. In response to this, there are examples of underused private green spaces being shared as commons in the US. However, this is only possible when populations get together and get involved. And not everyone has the time, energy, or the capacity to do so.

This is particularly true for vulnerable populations, who might struggle to make ends meet. In some cases, vulnerable neighborhoods might be overly solicited by researchers and municipalities in a way that might cause participant fatigue and stigmatization. Participants might also feel like such activities raise their expectations in terms of environmental improvements which are then not delivered.

However, civic participation, in particular of vulnerable populations, remains essential in order to avoid gentrification and to deliver the most health benefits. Although having green spaces available provides some health benefits, engaging with such spaces either alone or as part of a community is shown to deliver significantly more (WHO, 2017).

Finally, we hope that our recommendations help facilitate the engagement with urban green spaces of society in its broadest representation, whether you are a researcher, practitioner, or user of urban green spaces, human health, and well-being is a common purpose.

Marthe Derkzen, Agnès Patuano, Takemi Sugiyama, John Boon, Andrea Ramírez-Agudelo, & Arthur Feinberg

Arnhem/Nijmegen, Wageningen, Melbourne, Amsterdam, Bonn, and Rotterdam

about the writer

Agnès Patuano

Dr. ir. Agnès Patuano is an Assistant Professor in Landscape Architecture and Spatial Planning in Wageningen University (The Netherlands) and an expert on landscape architecture and human health.

about the writer

Takemi Sugiyama

Professor Takemi Sugiyama is the leader of Healthy Cities research group in the Centre for Urban Transitions. Building on his background and research experience in architecture, urban design and spatial/behavioural epidemiology, he explores how urban form (building, neighbourhood environments) can be modified to encourage active living and enhance population health.

about the writer

John Boon

Landscape architect John Boon (Hoorn, 1969) has been committed to making our cities healthier. Since 2005, John works at Arcadis where he is head of the landscape architecture and urban design team. In addition to his work at Arcadis, John is a member of the Executive Committee of IFLA Europe, and a member of the Supervisory Board of USH.

about the writer

Andrea Ramírez-Agudelo

Andrea holds a Ph.D. in urban sustainability, and her experience in science, policy, and practice has motivated her to look for strategies to facilitate knowledge sharing for urban transformations and a more sustainable future.

about the writer

Arthur Feinberg

Arthur is a postdoctoral researcher at the Erasmus University (Rotterdam), focusing on social resilience through citizen initiatives: the urban commons and social community enterprises such as cooperatives.

References

Barthel, S., Colding, J., Hiswåls, A. S., Thalén, P., & Turunen, P. (2022). Urban green commons for socially sustainable cities and communities. Nordic Social Work Research, 12(2), 310-322.

Beute, F., Andreucci, M.B., Lammel, A., Davies, Z., Glanville, J., Keune, H., Marselle, M., O’Brien, L.A., Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Remmen, R., Russo, A., & de Vries, S. (2020) Types and characteristics of urban and peri-urban green spaces having an impact on human mental health and well-being. Report prepared by an EKLIPSE Expert Working Group. UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

Camps-Calvet, M., Langemeyer, J., Calvet-Mir, L., Gómez-Baggethun, E., & March, H. (2015). Sowing resilience and contestation in times of crises: The case of urban gardening movements in Barcelona. Partecipazione e conflitto, 8(2), 417-442

Colding, J., Barthel, S., Bendt, P., Snep, R., Van der Knaap, W., & Ernstson, H. (2013). Urban green commons: Insights on urban common property systems. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1039-1051

Deng, Z., Lin, Y., Zhao, M., & Wang, S. (2015). Collaborative planning in the new media age: The Dafo Temple controversy, China. Cities, 45, 41-50.

Derkzen, M.L., Bom, S., Hassink, J., Hense, E.H., Komossa, F. and Vaandrager, L. (2021). Healthy urban neighborhoods: exploring the well-being benefits of green citizen initiatives. Acta Horticulturae 1330, 283-292.

Kuymulu, M. B. (2013). Reclaiming the right to the city: Reflections on the urban uprisings in Turkey. City, 17(3), 274-278.

Mitchell, R. J., Richardson, E. A., Shortt, N. K. Pearce, j. R. (2015). Neighborhood Environments and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Mental Well‐Being. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49, 80‐84.

Rao, A. (2013). Re-examining the relationship between civil society and the internet: Pessimistic visions in India’s ‘IT City’. Journal of Creative Communications, 8(2-3), 157-175.

WHO (2016). Urban green spaces and health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Europe.

Wolch, J.R., Byrne, J. and Newell, J.P., (2014). Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landscape and urban planning, 125, pp.234-244.

Leave a Reply