As urban environments become more cosmopolitan, there is an increasing urgency to think critically about how to care for and be in relation to novel ecosystems and the plants they support. Artists and cultural creatives are showcasing a range of strategies to help shift worldviews, to embrace the traits of plants we deem invasive, and to begin a long process of healing and building empathy for the more-than-human world.

In early September 2019, a plant known as Jimson weed (Datura stramonium) was considered one of the top threats to public safety in New York City. Although fairly common in the region, a Tweet from Adrian Benepe, the former commissioner of NYC Parks & Recreation went viral after he found a specimen growing on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Within a day, local media outlets like the New York Post and an NBC affiliate circulated sensational headlines warning that one touch of this “killer” plant could turn you into a “zombie”, and cause convulsions or hallucinations. A post from the neighborhood blog Patch.com even went so far as to trace the history of the plant to Nazi Germany and the Manson family, alleging it was used as a poison in cult sacrifices.

While indeed, Jimson weed can be poisonous, it also provides a number of benefits or ecosystem services ranging from creating a habitat for nocturnal pollinators and moths, helping to filter air, stabilizing soils, and absorbing stormwater, and is used by Indigenous communities to treat mental illness, tumors, infections, and more. Despite this, headlines about plant and insect invasions are on the rise, filled with war-like rhetoric that seems to insinuate humans are in a battle with so-called alien invaders. Scholars and artists alike have been warning us for decades that these invasive narratives are not only xenophobic but perpetuate notions of human exceptionalism which can have a negative influence on our attitudes towards urban nature at precisely the same time we are suffering from a biodiversity crisis. This not only contributes to a biased view of naturally occurring plants but also distances urban dwellers from the lifeworlds of species they regularly encounter. While management and monitoring of changes to species diversity are important, ecologists increasingly argue we need to think differently about how best to manage and find kinship with the plant communities they support. Not only because of the multiple benefits they provide but also because of the equity, justice, and governance implications they present to communities.

Today, whether we like it or not, cities are now composed of novel ecosystems, which are self-assembling biotic communities that emerge in sites of disturbance with little or no human management. Chances are you’ve encountered some and haven’t even realized it ― from vacant lots and post-industrial sites, along roadways, and even in your backyard. In large part artists, designers and other creatives are on the cutting edge of developing new methodologies and creative actions that seek to repair our relationship to these sites and the urban plant communities they support. Here I want to explore some examples of what artist Ellie Irons describes as an emerging form of “eco-social art” ― artworks and creative practices that aim to cultivate a sociality in plant-to-human interactions and draw from new fields of study like critical plant and multispecies studies, and also emerging concepts such as Donna Harraway’s “naturecultures” or Robin Wall Kimmerer’s notion of “biocultural”. We’ll start with some initial grounding and context, and then consider three methods artists are using to envision a world beyond humans.

The emergence of invasion biology and the multispecies vegetal turn

In the US, the war on weeds and invasive species is nothing new and has shaped policy on land management and conservation for decades. Although there are many historical trajectories, much of the disdain toward “exotic” or “alien” species can be traced back to the early histories of European colonization. In a North American context, the arrival of colonists brought with it not only a divine calling to seize occupied lands but also many seeds and specimens of plants from Europe and other parts of the world, as well as a Western ethos of agriculture that continues to drive land stewardship today. The field of invasion biology, or the study of the adverse effects of “invasive alien species”, also plays a pivotal role. Mark A. Davis, a historian of invasion biology, points to the publication of Charles Elton’s “The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants” (1958) as an important milestone in the formalization of the field and popularization of the term “invasive alien species”. Research from Elton and other scientists quickly inscribed the notion of “biological invasions” as a preeminent threat to humanity, utilizing war-like language to describe certain plants and animals as potential “ecological explosions”. By the 1990s scholarship in the field had grown exponentially with many studies focused on the impacts of biodiversity on island nations, often used to support restoration agendas and conservation policies that do not reflect recent theories of ecological resilience or adaptation.

In a recent piece for the art space Pioneer Works, Banu Subramaniam reminds us that invasion biology, even today, suffers from a kind of collective amnesia by failing to recognize the centuries of human and more-than-human interactions that have continually shaped ecosystems across the globe. Today more than half of the plants deemed invasive in North America were actually brought here purposefully as agricultural imports or exotics cultivated for various purposes. Yet still, the Society for Ecological Restoration refuses to acknowledge the value of ecosystems that happen to harbor these plants and to update its International Standards to focus more on understanding the function and benefits of ecosystems. This is not to say that ecological restoration efforts have no value, in fact, they can be critically important in many parts of the world, especially in biodiversity hotspots where the abundance of certain species is critical for maintaining food webs and ecological services urgently needed worldwide.

However, the question of how we discuss these emerging issues remains a key concern. Many in the field highlight how the discourse of invasion negatively influences our perception of urban environments and supports restoration practices that aim to recreate the “historical continuity” of an ecosystem by attempting to “restore” or bring them back to some arbitrary time in the geologic record. Ecologists largely agree this is nearly impossible and quite subjective given natural systems are continually changing and impacted by human activities. What’s more, despite continued efforts to prove invasive species are a driver of extinction or biodiversity loss, the majority of global studies conclude that ‘alien species invasions’ have not resulted in any significant threat (See The New Wild by Fred Pearce). Many ecologists now agree that invasive species are merely passengers of disturbance and that climate change and human activities impact biodiversity more significantly. Nonetheless, most approaches to ecological restoration or conservation in the US remain unchanged, requiring expensive, carbon-intensive practices, and herbicides that are often not effective long-term and divert resources away from addressing the very systems driving biodiversity loss in the first place (See Tao Orion’s Beyond the War on Invasive Species). And it’s important to note, that this is not an issue resigned singularly to parks or natural areas but is, in fact, something inscribed into most local zoning and property ordinances, making it illegal to harbor any plants considered to be invasive or noxious above 10-12 inches.

Today, our perception and attitudes towards naturally occurring plants continue to be shaped by multiple forces ― from popular media to the social pressure and legal responsibility to maintain a manicured lawn, to political and cultural ideologies that presume nature is merely here to serve human ends. This has cultivated what many call a form of “plant blindness”, where we tend to ignore the value and presence of plants in our daily lives or demonize the perceived traits of weedy plants which many assume to be parasitic, destructive, and aesthetically displeasing. This is not something innate but rather learned over time, which I argue contributes to an implicit bias against naturally occurring plants and urban nature. A number of scholars have attempted to better understand this, notably Joan Iverson Nassauer’s (1995) research on landscape perception and the “Cues to Care” framework, which finds that many people prefer landscapes they recognize as designed or signal ongoing human care rather than semi-wild or unmaintained areas. Yet, decades after Nassauer’s work has circulated, little has been done to radically reorient how we conceive of and manage urban greenspaces and natural areas, prompting what many call a vegetal or multispecies turn in thinking about a range of fields/practices.

In recent years “multispecies thinking” has emerged as a way to consider the interdependencies between humans and other species. Examples range from multispecies ethnography, to kincetric ecology, ecological art, or the concept of “multispecies urbanism” which advocates for consideration of the well-being and needs of nonhumans within planning and design to ensure mutual flourishing and survival. Interdisciplinary scholars like Donna Houston, Anna Tsing, and Debra Solomon even promote the idea of “multispecies entanglements” to build empathy and relationships with organisms we may deem a nuisance or invasive. They describe this as a process of attunement involving interactions with urban nature that integrate embodied practices, Indigenous knowledge, and new ways of knowing to envision strategies for communication and inclusion of more-than-human actors, especially organisms we label as invasive, alien, or feral.

The turn toward multispecies thinking is also informed by a long trajectory of what others describe as a ‘vegetal turn’ in art, philosophy, and other fields noting how human history has been shaped by interactions with the plant world (For additional information read Vegetal Entwinements in Philosophy and Art). Anthropologist Natasha Meyers’ proposition of the Planthroposcene, in many ways, encapsulates this ethos. Meyers argues that because plants are the precursor to all life on the planet, (e.g., cyanobacteria, or aquatic plants found in the ocean made an oxygen-rich atmosphere possible 2.4 billion years ago) then we actually live in the Planthroposcene, an era shaped and enabled by plants. While Meyer’s proposal is purposefully provocative, concepts like the Planthroposcene are not necessarily useful unless we develop meaningful ways for others to reconsider our relationship to plants, advocating for interdisciplinary approaches that include the arts. Let’s take a look at some examples. [Note: It’s important to note the examples are drawn from my own experiences in the North American context, and do not necessarily reflect the diversity of approaches across the world.]

Using embodiment and somatic practices to cultivate vegetal kinship

The use of movement-based practices to connect people with plants has many histories. In the US, emerging art movements like Dadaism and Fluxus influenced new interpretations of classical dance and dramatic arts, inspiring experimentation with forms such as performance art and guerrilla theater. Works by Betsy Damon (A Shrine for Everywoman, 1980-88) and Mierele Ukeles (Touch Sanitation, 1979–1980), Anna Halprin (Planetary Dance: People power for peace, 1980), and Meredith Monk (On Behalf of Nature, 2013) among others seized this moment and created opportunities to explore the body’s relationship to plants and the environment. But when it comes to artists using embodied approaches to engage with novel ecosystems, this is a more recent phenomenon.

One example is artworks developed by the Environmental Performance Agency (EPA). In 2017, I co-founded the EPA, an artist collective using artistic, social, and embodied practices to advocate for the agency of spontaneous urban plants with collaborators Andrea Haenggi, Ellie Irons, and Catherine Grau. The EPA was founded in the wake of the 2016 US presidential election of Donald Trump and the subsequent dismantling of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under administrators Scott Pruitt and later Andrew Wheeler. Realizing the urgency of the situation, we created an alternative EPA as a political and artistic gesture focused on learning from spontaneous urban plants and cultivating what EPA Agent Irons describes as ‘plant-human solidarity’, noting the ways we are “entangled with vegetal life as a foundational aspect of working towards eco-social justice”.

EPA agents work primarily through forms of somatic and performative practices that aim to cultivate a critical space for encounters between people and disturbed landscapes. Projects range from opening a fictional EPA field office in Washington DC called the Department of Weedy Affairs, to launching an online platform called the Multispecies Care Survey, to a practice we call public fieldwork which involves using movement, improvisation, and field science to engage with urban weeds in cities. EPA agents often use scores as a device to structure encounters, a loose set of instructions that invites the public to directly encounter, learn from, and be in relation to weedy plants or what EPA agent Haenggi calls “ethno-choreo-botan-ography”. One of our first projects was the Urban Weeds Garden cultivated within a 1,900-square-foot “vacant lot” in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Over several years the site, once an auto repair shop, was left to go wild and supported a dizzying array of 50+ species of plants and organisms (both “invasive” and native). We began to invite the public into the space, hosting improvisation workshops, and experimenting with scores and protocols to envision a world beyond humans.

In one example, EPA agent Andrea Haenggi created a score called “Embodied Scientist: Creating Weedy Plant Labels.” After a brief introduction, a participant is invited to locate a plant they feel drawn to and to focus on the plant’s movement, shape, texture, and smell. Next, the participant is invited to change their body’s position, to be in relation to the plant in different ways, and to develop a movement in response. Finally, the participant creates a label for the plant, encouraging them to rewrite its story and imagine a new name and origin that rejects the classical Linnaeus binomial system. The label is then placed next to the plant.

What we found through these engagements was a marked change in how participants spoke about plants they may have overlooked just a few hours ago, as well as a kind of bodily awareness of the margins and edges of urban space. We would often receive follow-up text messages the following day or week with images of weeds and reflections. Return visitors would also bring specimens, and notations on wild garden plots they had found in the city as well as questions about how naturally occurring plants can be used as medicine, food, or resources for dyes and art making. Here we view the artwork not as a singular object or ephemeral experience, but rather a sensorial ongoing encounter that creates a lasting memory and space to confront our assumptions about plants and spaces we see as damaged, disturbed, or out of place. An embodied methodology in this sense invites a sensory immersion and interruption to the everyday ritual of city life that can cultivate an opportunity for shifting worldviews. Scholars like Elizabeth Ellsworth (2005) describe this as a “nonlinguistic event”, where the mind, body, heart, and soul coalesce in our experience and make sense of the world. As we engage and participate, learning unfolds as a radically relational activity, a network of experiences and unconscious awakenings.

Social resilience and communities of practice

Increasingly artists create spaces for learning and social exchange exploring issues related to novel ecologies and naturally occurring plants. These artworks and projects can cultivate meaningful communities of practice or a group of individuals who come together to share a common interest and engage in learning and collaboration. Through engaged work together, a process of social co-participation between a learner (or newcomer) and a member of a community of practice (or old timer) unfolds, and often allows one to delve deep into new discourses or worldviews.

One example is the Grafters X Change, initiated by artist Margaretha Haughwout, a collaborative project that explores the politics and potential of grafting fruit-bearing branches onto non-fruit-bearing trees in urban and post-industrial landscapes. Each exchange unfolds as a regional gathering of fruit tree enthusiasts who share scionwood and seeds, skills, fruit foods, and art projects and practices. The aim in many ways is to make visible the labor and expertise involved in ecological restoration, urban agriculture, and to interrogate forms of environmental care. As communities of practice form, the group experiments with different grafting techniques, sharing bioregional resources for food sovereignty, and stories that echo the implications of monoculture street tree plantings. A key element of each Grafters X Change gathering is also a critical examination of what Haughwout describes as “invasive thoughts” in a publication created for the 2022 event at Colgate State University:

Interrogate your belief system and your (perhaps invisible) relationship to settler-colonial coercion. If you have the knowledge to call a plant or critter “invasive,” you probably have the skills and tools to investigate why they are here in the first place. Ensure your stance in the landscape is not simply prolonging a harmful legacy of power-over mentality. Hold humility close and don’t you dare call yourself a “Master Gardener.”

In New York City artist Candace Thompson launched the Collaborative Urban Resilience Banquet in 2019, which she describes as a multi-species experiment exploring how to adapt to the climate crisis by meeting (and eating) our non-human neighbors. Through community science experiments, dinners, foraging walks, and social media storytelling, Thompson explores food-based justice by learning from and with weedy edible plants, and organisms considered invasive. She forages and prepares the food in preparation for large gatherings she calls banquets, inviting the public to quite literally consume the very things we label as pests or invasive. Thompson diligently tests and researches the food stuff collected, measuring the concentration of heavy metals and other contaminants often found in urban soils, and then compares her findings with similar tests performed on ingredients found in local supermarkets. Thompson regularly finds that the levels of certain contaminants are actually quite higher in the supermarket, in comparison to plants collected at a brownfield or post-industrial site. Her activities are rarely singular, inviting communities on foraging walks, to dinners and performances that forge a community of practice.

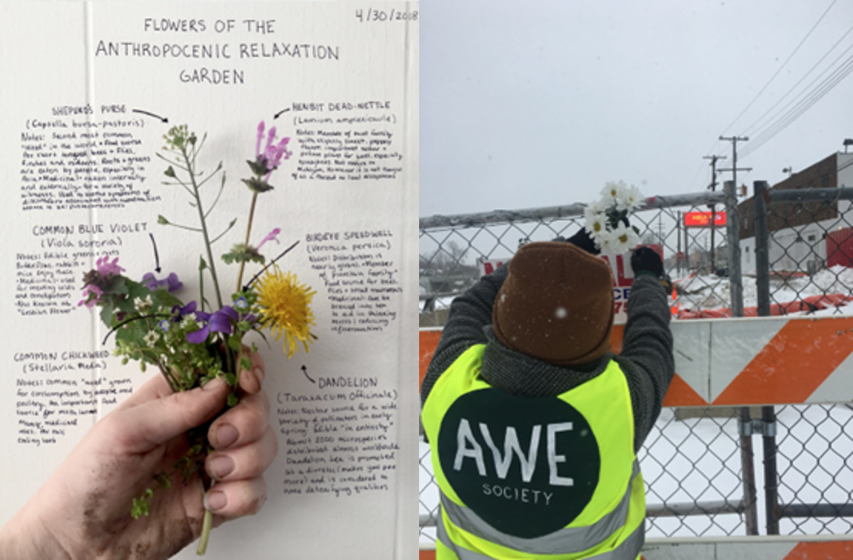

In Detroit, Michigan, artist Bridgette Quinn established the A.W.E. Society (Area Wilds Exploration Society) as a platform inviting the public “to play within the borderlands between the city and nature, between the psyche and the environment.” Quinn utilizes society as a mechanism to bring together diverse groups of people to tour urban creeks and greenspaces contaminated by nearby auto and oil refineries. The Society’s activities often include elements of acoustic ecology, collecting the sounds of a newly hybridized landscape, and the plants and organisms that coexist. Sometimes the work becomes political. In The Resonant Underbelly, Quinn sought to explore creeks and running water near her home, leading her to a culvert in Warren, Michigan. When she looked closely at the water, she discovered an oil spill and E. coli contamination, a finding she submitted to the Warren City Council in 2018. Despite fairly convincing evidence, the city did little to address the issue prompting Quinn to invite participants on a kayak tour of the creek where they engaged in improvisational singing in creek culverts. The field recording was pressed into a limited-edition vinyl record, with one side the sounds of the creek, and Quinn’s testimony at the Warren City council hearing.

One last example comes again from Ellie Irons and her collaborator Anne Perccoco. In 2013, they launched The Next Epoch Seed Library (NESL) which collects and preserves seeds from plant species that are considered invasive or opportunistic within their respective ecosystems. Through workshops, foraging walks, and seed burial performances, the NESL creates a platform for artists, scientists, and communities interested in studying and understanding these plants and their potential uses. By gathering and sharing seeds, the project recognizes the ecological and evolutionary significance of these plants and seeks to explore their potential contributions to future ecosystems in a changing climate. Through the seed library and foraging walks, individuals and communities can access seeds for artistic projects, scientific investigations, and ecological experiments.

In these works, the co-creation of a community of practice surrounding issues of invasion, novel ecologies, and plants has the potential to create spaces for dialogue and circulate public pedagogies that may not surface otherwise. The communities of practices that form also have the potential to cultivate and improve social resilience, or the capacity to make meaningful connections with others and the ability to increase well-being and health. In conversations with each of the artists who created these works, they attest that creating alternative spaces for exchange can help address fears and assumptions surrounding the role of naturally occurring plants and importantly motivate a radical kind of stewardship for disturbed ecologies. I like to think of these inflection points as ruderal carescapes ― places where communities can begin to develop a relationship with damaged terrains, which may help reframe conventional notions of care and restoration toward regenerative models of self-healing and mutualism. And raise important questions about the ethical obligation to care for more-than-human worlds.

Spaces of encounter, confrontation, and healing

Artists experimenting with eco-social practices also work within and around the confines of art institutions and spaces, creating spaces for encounter, confrontation, and healing. One example is Brazilian artist Maria Thereza Alves’ artwork, Seeds of Change (1999-ongoing), which has traveled to multiple locations across the world, exploring the historical, cultural, and ecological significance of plants and their role in shaping human societies. Alves specifically highlights ballast flora (seeds/plants brought over on cargo ships) from the port cities of Europe exploring how the global redistribution of plant species through colonial and imperialist endeavors has impacted diverse cultures throughout history. She creates participatory installations in museums, galleries, or community spaces consisting of display cabinets, containers, and sculptural gardens where the seeds are grown, or meticulously arranged and labeled with detailed information about their origins and histories.

Similarly, artist Okoyomon, a Nigerian-American artist has created participatory installations and artworks exploring the politics of invasive species. In their immersive exhibition of her work “Earthseed” (2020) at the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, Okoyomon installed young kudzu vines and mounds of topsoil in the Zollamt gallery highlighting how the plant was used in the American South to address issues of soil erosion when cotton was grown extensively in the region. Rather than presenting kudzu as a rapacious weed to be exterminated, Okoyomon uses the plants as a living medium to help cultivate a habitat for other organisms and as a support structure for six faceless “angels”, constructed from black lambswool, dirt, wire, and colorful yarn. Like Alves, Okoyomon explores how plants portrayed as ominous or deadly can help surface underrepresented histories.

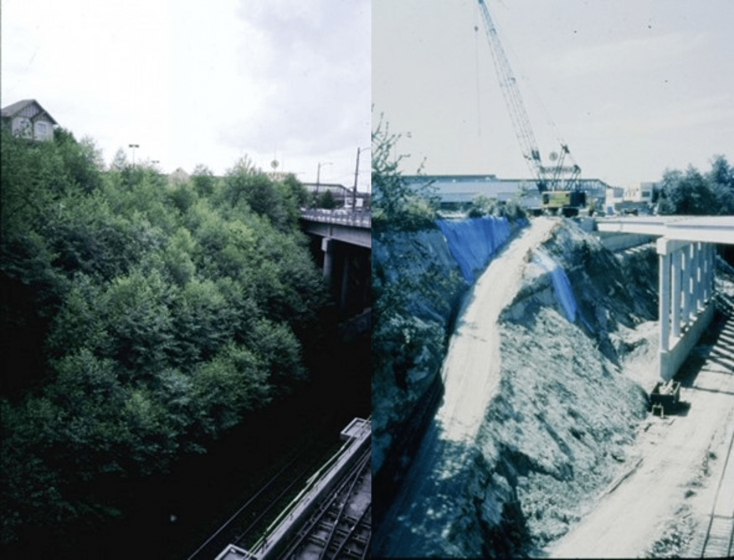

Finally, in Toronto and other cities across the world, artist Oliver Kellhammer creates work that intersects with invasive plants and post-industrial landscapes. Through his artistic practice, he explores the ecological and social dimensions of these landscapes, focusing on themes of regeneration, resilience, and the adaptive capacities of both plants and communities. In projects like other gardens, he invites participants to explore overlooked gardens that he characterized as ‘ruderal’ or plants growing from wastelands, dumping sites, or post-industrial. In other works, Kelhammer experiments with methods such as ecological restoration, permaculture, and community gardening to transform degraded or abandoned sites into vibrant and productive spaces. He often works with invasive plants like cottonwood as pioneering species that can help regenerate soil, provide habitat for wildlife, and improve overall ecosystem health. In works like Healing the Cut Bridging the Gap (1992), he uses hundreds of willow and cottonwood cuttings, which would root and stabilize the soil until the original alder and big-leaf maple forest re-established itself.

Co-creating a world beyond human

Further research to assess participatory art methods is urgently needed, especially as the presence of novel ecologies and urbanization accelerate. In finding ways to reframe how we relate to and kind kinship, even with organisms we deem a nuisance or pest, there may be an opportunity for greater understanding of the systematic drivers of ecosystem change worldwide, as well as mutually beneficial approaches to care for, conserve, and reimagine disturbed environments as sites of possibility and not merely spaces devoid of life.

Artists and cultural creatives are showcasing a range of strategies to help shift worldviews, to embrace the traits of plants we deem invasive, and to begin a long process of healing and building empathy for the more-than-human world. If we take Meyers’ assertion that our history and survival are indeed indebted to plants, then the call for plant-human solidarity needs to be taken seriously, especially in this time of incredible change and disruption.

We are now living in the Planthropocene. This is a time to listen to our plant allies, to repair a broken trust, and support the many creative communities working to envision multispecies kinship. The next time you see a weedy friend, try to find an opportunity to meet the plant, to listen, and find resonance. You might find they have something to tell you, but first you have to be open to listening.

Christopher Kennedy

Austin (Working in New York City)

Leave a Reply