Many of the challenges we are experiencing in cities and communities around the world are connected to water. What we can do to make our water flow in abundance, and life on this planet thrive again?

In 2010, the UN General Assembly explicitly recognized the human right to water and sanitation. Equal access to safe and clean water, however, requires a major change in how decisions over use and rights to water are made and needs appropriate legal frameworks to curb over-extraction and unsustainable behavior.

Qanats are an ancient system of under-ground water channels in Iran that together equal the distance from the earth to the moon; they are now recognized as a World Heritage site. They are still in use for agriculture and livelihoods in arid regions of the world. They give back water to nature and have given life to millions of people over centuries. They are an excellent example of sustainable water management solutions that remain valuable over time.

Water is our source of life but, unfortunately, it often features in the news through stories of crisis: flooding, droughts, oceans filled with plastic, water pollution, scarcity, and contamination of drinking water. Populations of migratory fish have fallen by three-quarters in the last 50 years (The World’s Forgotten Fishes, 2021). In 2020, 6.13 billion people were living in critically water-insecure or water-insecure countries, (Global Water Security Assessment 2023). Around one-quarter of the global population lives in water-stressed countries, and by 2050, 5.7 billion people are likely to live in water-scarce areas, while the number of people at risk from floods is projected to rise to around 1.6 billion (UNEP, 2023).

Water deserves all our attention, as it is essential for life on earth and for all business and economic activities. The reason why I want to dedicate this essay to water is to better understand how the challenges we are experiencing in cities and communities around the world are connected to water and what we can do to make our water flow in abundance, and life on this planet thrive again. The aim is to give insights into water-related challenges and the value of restoring nature in addressing these challenges.

Even though we may think that we are in dire water straits, there are a range of solutions that we all can contribute to. The secret to some of these solutions is trees. Forests have a crucial role in regulating the water cycle and the frequency and intensity of rainfall (Global Environmental Change, 2017). Restoring forests and natural landscapes can impact water cycles, water availability and quality, and climate change adaptation in extraordinary ways.

Universal water challenges

A growing demand from an increasing world population, insufficient infrastructure, climate change, pollution, overexploitation, and flawed water governance lead to multiple water-related challenges around the world.

Every year, we withdraw 4.3 trillion cubic meters of fresh water from the planet’s water basins. We use it in agriculture (70 percent of the withdrawals), industry (19 percent), and households (11 percent). We often are not aware that all industries depend on water for some part of their production processes: for food and beverage companies the water use is obvious, but metal and mining companies need water for dust control and drilling, data centers require water for cooling and apparel companies rely on water to grow cotton and wash garments (McKinsey, 2020).

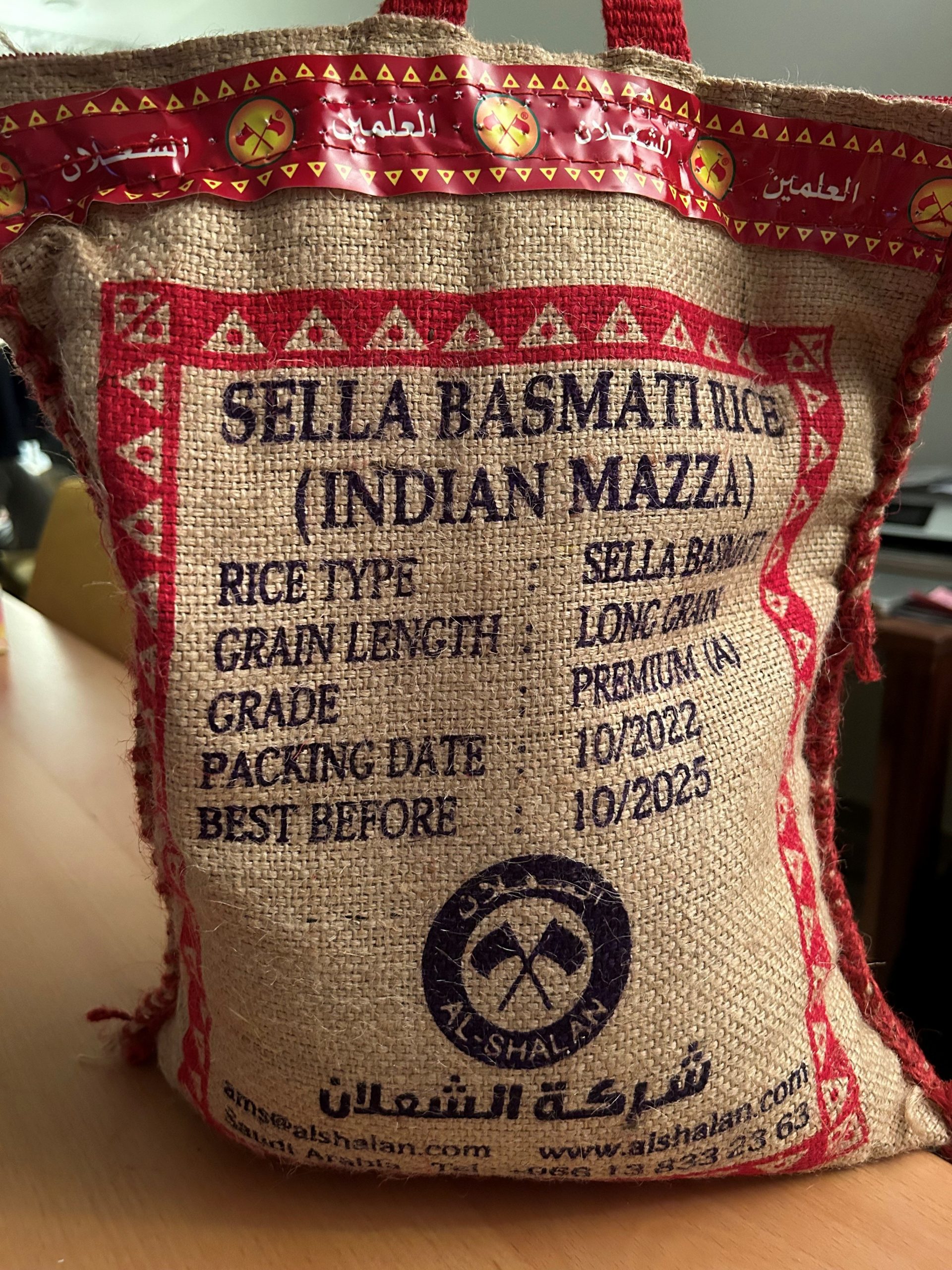

An example is the export ban on rice in India. India is the world’s largest rice exporting country, providing around 40% of the world’s supply, 22 million tonnes in 2022. India is home to 18 percent of the world’s population but only has 4 per cent of the world’s water resources, which leads to high levels of water scarcity. To grow rice, water is added to aid weed management and increase nutrient uptake for higher yields, so-called “ponding conditions”. This consumes 60 million litres of water per acre of rice paddy, or the equivalent of a hundred households’ domestic water consumption a year. The volume of water used to grow rice cannot be replenished by rainfall alone, therefore farmers pump groundwater to irrigate their paddies, up to 5,000 litres for every kilogram of rice produced. This means that water is exported with rice production rather than used for meeting domestic needs. Last year at least 47 billion liters of water were used to increase rice supply to sell overseas. Transition to other less water-intensive crops, such as millets or pulses, vegetables, and fruits may be needed in the coming years.

The supply of fresh water has been steadily decreasing while demand has been rising. In the 20th century, the world’s population quadrupled—but water use increased sixfold. A study on freshwater stress and storage loss published in Nature last year (Huggins et al. 2022) indicates that the most vulnerable freshwater basins encompass over 1.5 billion people, 17% of global food crop production, 13% of global gross domestic product, and hundreds of significant wetlands.

Water is a growing business risk and to tackle this, companies need to understand how they are interacting with basins that are projected to become water stressed and prioritise efforts there. Companies can focus on several areas of action to help mitigate water stress: direct operations, supply chain, and wider basin health. Some companies are already taking action in all three areas. Apple, for example, anchors its water stewardship policies by mapping its global water use against regions with heightened water risk.

In partnership with The Nature Conservancy, Starbucks China pledges to replenish at least 1.5 million tons of water annually to Qiandao Lake, by the beginning of 2030. Qiandao Lake is the largest manmade freshwater lake in the Yangtze River Delta and a vital water resource for 10 million residents in Hangzhou, Jiaxin, and other areas in Zhejiang province. By focusing on sustainable agriculture and wetlands restoration, this partnership will meet the annual water consumption needs of 23,000 citizens in the vicinity. As water is essential to the Starbucks agricultural supply chain and store operations, it aims to give back water used by protecting surface water against pollution and allowing water from rain, storms, and rivers to naturally replenish the local ecosystem. It entails the restoration of 2 hectares of wetlands and support to local farmers to implement sustainable agricultural practices for their crops, to reduce the use of fertilisers and pesticides, reduce soil erosion and surface runoff while improving yield.

All these examples of business and economic activities that depend on water, demonstrate that insight into risks and the need for efficient use of water is not sufficient to ensure equal access to clean and abundant water, in particular in cities and water-scarce areas, such as India and China. Investment in water infrastructure and measures for water saving and groundwater management and water price reform are important actions, but effective legislation that prevents overexploitation and unsustainable water use is essential in every part of the world.

The origin of water and its use — biodiversity matters

To understand the state of water, it is important to start with the origin of water: more than 97% is salt water, held by our oceans. The remaining 3 percent of freshwater is mostly frozen in glaciers. What remains for drinking water is 1 percent. Availability of fresh water differs by location and the majority originates from a few hundred named basins, of which the Nile, Indus, Amazon, Congo, Yangtze, Mekong, and Colorado rivers are well-known ones. Freshwater can be found in lakes, ponds, rivers, streams, and wetlands, but also in less-obvious places: more than half of all fresh water on our planet seeps through soil and between rocks to form aquifers that are filled with groundwater. The top surface of an aquifer is called the water table, and this is the depth where wells are drilled to bring fresh water into cities and homes (National Geographic).

According to Hydrologist Emma Haziza, every species living on earth needs water as much as we do. Water extraction creates economic wealth and is part of everything that is produced and consumed, clothes, food, electronics, houses, cars, technology, and machinery but this destroys the water cycle on a planetary level. This leads to a loss of biodiversity as droughts increase.

With climate change and increasing temperatures, the water cycle is accelerated with more evaporation, evapotranspiration, and precipitation. The risk of torrential rains also increases and droughts occur more frequently. Emma Haziza has worked for more than 20 years on the International Panel for Climate Change projections and as we are currently noticing around the world, the scenarios for future drought are beyond what has been predicted. In parts of France for example, in one year of drought deep water reserves collapsed by more than 70%. Most parts of Europe experience extreme droughts, groundwater is overconsumed and water stress increases, as well as urbanization and soil sealing. Heavy agriculture machinery also prevents water from penetrating and reaching the groundwater and harms soil quality due to pesticides and fertilisers. Such lifeless soils have no water absorption capacity and harm the deep water table as they are unable to recharge. The way we treat the soil determines to a large extent the water resources available in the world’s aquifers. Without deep water tables, there is no river flow and life disappears.

Trees sustain biodiversity and climate resilience

By evapo-transpiring, trees recharge atmospheric moisture, contributing to rainfall locally and in distant locations. Trees’ microbial flora and biogenic volatile organic compounds can directly promote rainfall. Trees enhance soil infiltration and, under suitable conditions, improve groundwater recharge. Precipitation filtered through forested catchments delivers purified ground and surface water (D. Ellisson et al, 2017).

Species richness, particularly native species and forest rehabilitation can provide positive effects on the health of forests and their water-related ecosystem services. Forest rehabilitation offers opportunities to restore water-related ecosystem services (Ellisson et al, 2017).

Drought is not caused by a lack of water but by a failure to convert water vapor into viable clouds, rain, and a failure to retain that water on the earth within plants, soil, and water structures. Converting heat-holding water vapor into viable cooling low-lying clouds produced through bio-aerosols made by plants while protecting soils, is essential for combatting drought (Cindy Morris, INRA, 2017). Water retention landscapes, rich soil fed by micro-organisms and livestock nutrient cycling, cover crops, trees, and plants of all varieties producing as much foliage as possible, cool the earth, release necessary cloud seeding aerosols, and induce rainfall.

More information about the hydrologic cycle which explains the continuous journey of water between oceans, atmosphere, and land can be found here: NASA Water and Energy Cycle.

How nature brings water to life

Nature plays an important role in keeping urban water sources reliable and clean. Natural solutions, such as reforestation, better farming practices, river bank, or wetland restoration can reduce erosion and run-off that pollutes water. This can improve water quality and reduce treatment costs. The Urban Water Blueprint (Mc Donald, Schemie, 2014) analyses the state of water in more than 2,000 watersheds and 530 cities worldwide to provide science-based recommendations for natural solutions that can be integrated alongside traditional infrastructure to improve water quality.

The Urban Water Blueprint explains that source watersheds provide the natural infrastructure that collects, filters, and transports water. On average, the source watersheds of the largest 100 cities are 42 percent forests, 33 percent cropland, and 21 percent grassland, which includes both natural and pastureland.

Watersheds and their land use greatly influence the quality of water cities receive; it is a dependence that becomes clear when significant changes happen. Changes in land use, particularly the conversion of forest and other natural land covers to pasture or cropland, often increase sedimentation and nutrient pollution. Increased human activity and the expansion of dirt roads in source watersheds can also lead to many other pollutants increasing in concentration, impacting the cost of water treatment and the safety of urban water supplies (McDonald, Schemie, 2014). In the period 2000-2012, more than 40 percent of source watersheds have had significant forest loss, which results in growing water challenges. Protecting and restoring the natural functions of watershed areas, through forest protection, reforestation, riparian restoration, agricultural best management practices, or forest fuel reduction can improve water quality and regulate water flow. It can reduce the costs of drinking water provision while providing multiple other benefits for nature and people. For instance, New York City avoided having to build a filtration plant by agreeing to the conservation of the Catskill watershed, the main source of its drinking water, thereby saving US $110 million per year. The water that originates from the watershed complies with water quality standards as a result of natural filtration by trees, swamps, and soils on its way to NYC.

In a time where technological solutions are spreading with the speed of light, we need to keep an eye on ancient systems that have proved themselves over centuries of life on the planet. New is not always better. Trees and natural ecosystems offer some of the most effective solutions to water security and climate change mitigation and are much cheaper than technical solutions such as carbon capture and storage (Nathalie Seddon, 2022). What is most important, they offer additional benefits, such as water filtration, clean air, biodiversity, livelihoods, and health.

When Charles Darwin arrived in Rio de Janeiro in the early 1830s, there was a chronic lack of drinking water due to the deterioration of the forests surrounding the city. He observed the complete deforestation and soil erosion of the hills around Rio that resulted from sugarcane and coffee production. The same hills that today are covered in lush native forest. This forest is Tijuca, the largest replanted tropical forest in the world that was created due to long-term government laws, regulations, management plans, and conservation policies (Drummond, 1996). Seeds and seedlings from mountaintop forests were collected and replanted on the hills over the course of more than 20 years, which resulted in a new forest in which rivers and streams flow again, and that cleans the air and lowers the temperature for citizens of Rio.

Another example of natural solutions to water challenges is under development by the Weather Makers, an engineering company that is involved in an ambitious project to bring rain back to the Sinai Peninsula. As land use in the Sinai changed with overgrazing and depletion of water, the loss of vegetation prevented the formation of clouds, allowing more and more water to evaporate from the area, increasing the rate of desertification. The local population suffers from heat waves, sand storms, and flash floods. By looking at the peninsula on Google Earth, they discovered that the scars of old rivers crossing the desert are still visible.

Re-instating the hydrological ancient water cycle leads to a substantial increase in water sequestration, a decrease in land surface and air temperatures, combined with unprecedented carbon sequestration. The Weather Makers works with a range of partners to regreen the Sinai desert, starting with the restoration of Lake Bardawil and its surrounding wetlands and an integral planning approach for regenerative landscape development of a total area of ~30,000 km². The fertile marine sediments that are dredged from the bottom of the lake are used, as well as sustainable sediment treatment, freshwater management, water harvesting, and flash flood prevention. In this way, native vegetation can be brought back, and it will change the direction of the winds, bringing water vapour from the Red Sea and Indian Ocean back to the Mediterranean land and as well the rain that is so desperately needed. The restored wetlands will increase the presence of birds, add fertility and new plant species, improve water and food security, and provide extensive carbon sequestration benefits.

Reflecting on the earlier mentioned Qanats, which harvest and convey water in a sustainable manner without damage to the tapped aquifer, their success relies on the social systems, the so-called Qanat Civilisation. This allowed for peaceful and cooperative management of water in arid regions of the world for safe drinking water, food security, water quality, and sanitation and we can learn a lot from this at a time when the world faces increasing water scarcity. These social systems were based on deep knowledge of the natural environment, indigenous culture, communal trust, and social cooperation. The social institutions fostered by the Qanats spread to other realms of social life, becoming part of the social capital of the society.

The cultural and social structure of Qanats offers a foundation for optimising water and land use to ensure sustainable socio-economic development based on cooperation. Cooperation is essential for any successful solution and in relation to water and management of water sources and their distribution will require new forms of stewardship and trust as well as the sharing of ideas and knowledge. This will strengthen societal efforts for change within and across societies.

United for water and nature

During the UN Water Conference in March 2023, the Freshwater Challenge was launched: a country-driven initiative to leverage the support needed to restore 300,000 km of rivers and 350 million hectares of inland wetlands by 2030 to enhance water security, tackle climate change, and reverse nature loss.

Trees are among many other things, food suppliers, rain makers, water keepers, and oxygen providers. If we restore forests and our natural vegetation systems, temperature extremes can drop, and the hydrological cycle will restore their cooling potential and with that improve the health of soils and biodiversity. This may even help to mitigate geo-political tension, as water does not stop at borders, which makes trees also peace makers.

As the examples mentioned before demonstrate, restoring nature is of tremendous value to make our watersheds healthy again in every part of the world. There are many success stories to present, but what they all have in common is that investing in nature-based solutions brings many benefits. However, despite these benefits, raising the financial capital and political will for their implementation remains very challenging. It requires cooperation between all of society and across disciplines, awareness, education, and capacity building. Not one watershed, river, or wetland at a time, but with united efforts across the globe.

As Sumetee Gajjar in her TNOC essay from May 2019 points out: “as scholars are allowed to experience and visit a living ecosystem from the past, they may be able to imagine and wish to sustain nature of their cities in the future. The lake thus becomes a classroom”. She adds that this is not only through what we can learn by studying it as a living social-ecological system but also by simply existing alongside its physical and ecological presence.

Urgency and large-scale action towards regulation are essential to address the water-related challenges in a changing climate, and part of the solution is up-to-date information about water developments. Global Water Watch, by Deltares, WRI and WWF, is an excellent resource that provides high-resolution information on thousands of global reservoirs, estimates the current state of a reservoir, and maps surface water. This can help to determine priority areas for action by governments and the private sector to conserve and restore ecosystems and natural water cycles.

If water is to be everyone’s business, then stakeholders will need to unite in water-scarce countries to make some difficult trade-offs on the road to water resource security (Charting our water future, McKinsey). Some solutions may require potentially unpopular changes, such as higher prices and the adoption of water-saving techniques and technologies by millions of businesses, farmers, and households.

In large water basins, individual action by a particular city’s water utility may not make economic sense as many millions of people live in cities that rely on this water. Conservation action would benefit multiple cities and water users downstream. Although each action alone may not have enough benefit to solely fund conservation, collective action may make economic sense. In this way, the scale of the intervention will go from a local level to regional and beyond, developing approaches that strengthen the landscape-wide application of land use planning for the provision of ecosystem services.

Countries with largely informal water sectors can re-allocate subsidies to incentivize water conservation. Simply removing subsidies and adjusting pricing might incentivize more prudent use of water but would also lead to challenges for farmers or other water users who cannot afford additional costs. Therefore, market-based mechanisms and financing instruments have to be designed in an inclusive and equitable manner, as demonstrated by the ancient Qanats, making water available to all in a cooperative manner.

“Water is not a commodity – it is life-making material. We need to ensure every living being has access to it” – Sadghuru.

Chantal van Ham

Brussels

Leave a Reply