At least in one sector of society, there is a growing interest in practicing sustainable tourism that respects the environment, promoting practices such as ecotourism, the responsible use of natural resources, and the protection of marine wildlife.

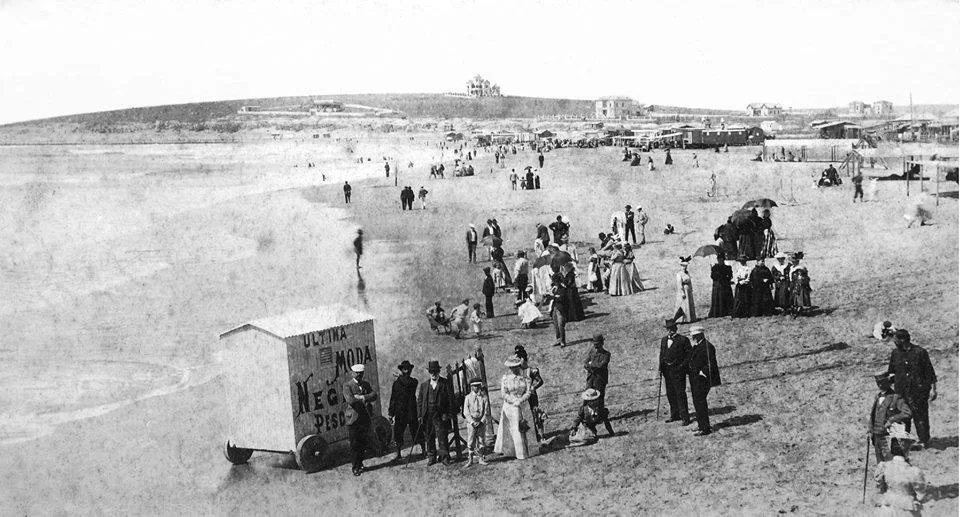

Sun, sand, and sea tourism is one of the most popular and widespread types of tourism worldwide. It originated in the healing practices of the 19th century when high society traveled to the beach seeking the health benefits of contact with salt water and sun exposure (Fig. 1). At the beginning of the 20th century, the middle classes joined the scene, and urban tourism triggered the transformation of coastal areas, where natural landscapes gave way to recreative waterfronts offering activities that fascinated tourists.

Leisure tourism became established in the first half of the 20th century because of economic growth and increased travel accessibility. It expanded from the 1960s onwards with the rise of tourism and improvements in infrastructure. Today, sun, sand, and sea remains one of the most important sectors of global tourism, with a wide variety of destinations tailored to different types of travelers who enjoy beaches, sunshine, and warm weather, and engage in all kinds of activities, especially water activities such as swimming, surfing, scuba diving, snorkeling, windsurfing, and sailing. Beaches offer an ideal setting for relaxation and disconnecting from daily routine (Fig. 2).

Sun and sand destinations often have well-developed tourist infrastructure, such as resorts, hotels, second homes, restaurants, and activities for all tastes. Many tourist destinations depend on these activities to generate income and employment, encouraging ever-increasing construction. Although the essential components are summarized in the well-known “sun, sand, and sea” formula, many contradictions lie behind it that are not always clearly resolved.

The occupation of the coastal sector with housing and infrastructure has been a global phenomenon on both islands and continents (Fig.3)

With the advance of urbanization along the coast, natural beaches have become urban ones. Although their primary objective is to enjoy the coastal landscape, these beaches have sacrificed their natural qualities over time in favor of infrastructure development and the consumption inherent in contemporary urban life. Although tourism advertising invites tourists to enjoy a beach in a natural setting, extensive and clean, with clear sand, transparent waters, cloudless blue skies, clean air, quiet, and expansive views, such advertising promises are rarely fulfilled.

Urban beaches are those most frequently visited by mass tourism and are not exempt from degraded environments. The construction of hotels, resorts, and housing in coastal areas leads to the loss of biodiversity and the transformation of the landscape. This is especially true through the modification of the geomorphological dynamics that supply sand to the beach and protect it from storms. Other impacts of urbanization include soil sealing and the alteration of natural biotic and abiotic mechanisms, especially those of environmental self-cleaning.

It is often forgotten that beaches are fragile ecosystems, and overuse can have negative effects on the environment, such as water pollution, the degradation of marine biodiversity, and the accumulation of debris in the sand. In gently sloping coastal areas, the shoreline mitigates storms, floods, and other extreme events. These benefits are diminished by the occupation and transformation of these lands.

Among the ecosystem services provided by beaches, erosion control, and storm protection are among the most valuable, especially in the face of extreme storms, and rising sea levels.

Currently, the main pressures or drivers of change on coasts are due to climate change which causes rising sea level rise, and increased precipitation, evaporation, storm intensity, and frequency. In the last decade, the pounding of waves from more frequent storms has led to the loss of buildings near the sea in many locations (Fig. 4).

The motivation to offer good quality beaches has led to certification initiatives, such as the international Blue Flag (1), the PROPLAYAS Beach Ranking (2), along with other national standards, which promote compliance with environmental regulations, so that beaches strive to maintain their natural appeal without compromising their ecological health (Fig. 5).

In certifications, beach accessibility is always a very important attribute. Good access, public transport, and parking are seen as a right that guarantees access to Nature, especially for people with reduced mobility. The Right to Nature has also been strengthened based on clearly tourism-related interests, where residents and tourists highly value easy access to the landscape, among other aspects such as infrastructure, safety, and services. The incorporation of accessibility criteria aims to encourage full enjoyment and participation by people with disabilities, guaranteeing access to the sand and even ocean bathing, as required by certifications such as the Blue Flag. However, increased accessibility can lead to the overexploitation of natural resources, especially in fragile systems such as coastal ones. Its increase facilitates urban development and attracts mass tourism, which often causes, as mentioned above, landscape degradation. The fragmentation of ecosystems and the loss of natural habitats undermine the Rights of Nature because they prioritize human demands over those of the natural environment. This dilemma continues to be evident in coastal landscapes, while natural resources are the mainstay of tourism, urban and recreational development is prioritized, negatively impacting the landscape (Fig. 6, 7).

We explored a database provided by the 2024 Beach Ranking. In 147 urban beaches in 10 countries (Argentina, Spain, Cuba, Colombia, Ecuador, Brazil, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Guatemala, and Mexico) we analyzed 17 variables that estimated the beach’s vulnerability to erosion, especially due to rising sea levels and frequent storms. The results showed that the beaches only covered 70% of these services, so their resilience was compromised. These are the preliminary results of research we are conducting presently. We are interested in exploring how accessibility can pose a threat to the natural contributions of the coastal system to protection and conservation.

Given the current climate change challenges, it’s worth asking what the new role of the seafront in coastal locations should be? Because it can no longer be thought of only from the aesthetic and hygienic perspective that has prevailed since the late 19th century, or the recreational role in the 20th century.

Today, when thinking on how to manage coasts, we should strongly consider previously overlooked functions. The coast should be viewed as a natural barrier to erosion and flooding, one that adapts to and mitigates climate change. Large areas covered with vegetation would help sequester greenhouse gases and improve climate comfort due to rising temperatures.

It is essential to control coastal development, maintain conservation areas, marshes, and vegetated natural dunes that guarantee the supply of sand to the beach, sediment capture, hydrological regulation, and water availability that allows for the provision of fresh water through rainwater infiltration. Balancing tourism with the environmental value of beaches is often a difficult challenge. We must first combat the denialism of many who are only willing to react to catastrophes, nor can we wait for voluntary solutions alone.

Beach quality certifications like those mentioned above are the way forward. While they are currently voluntary, the possibility of making them part of the obligations to be met by both concessionaires and the municipality would contribute to the required solutions.

Sun and beach tourism remains one of the main motivations for travelers and is a driving force for the economy and a real estate attraction. At least in one sector of society, there is a growing interest in practicing sustainable tourism that respects the environment, promoting practices such as ecotourism, the responsible use of natural resources, and the protection of marine wildlife. Communicating these new challenges to the community will be key to achieving a balance between the enjoyment of these destinations and their conservation for future generations.

Ana Faggi

Buenos Aires

References

Mir-Gual, M, Pons, GX , Martín-Prieto, JÁ , Rodríguez-Perea, A (2015). A critical view of the Blue Flag beaches in Spain using environmental variables. Ocean & Coastal Management 105, 106-115. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0964569115000046

De Oliveira E., Botero, CM (2024) Reporte de Evaluación y Ranking de mejores playas. https://rankingmejoresplayas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/reporte_ranking_2024.pdf

Leave a Reply