Living green and being mindful of the remote and rural impacts of our green urban living are more than just trends. They are political and ethical emergencies, and also our daily choices. And water—this silent presence that inhabits our bodies, landscapes, and cultures and inspires our work—may be the best guide on this journey.

about the writer

Wythaker Abreu

Wythaker Fernando dos Santos Abreu Junior is a Brazilian executive with expertise in commercial strategy, market development, and stakeholder management. He has led multi-million-dollar projects and high-performance teams in industries such as construction, education, and consumer goods. With a background in marketing and strategic planning, he combines technical knowledge with practical leadership to drive sustainable business growth.

Long before us, there was water. It has always been there, raining and flowing, long before streets, maps, and geopolitics. Even before we learned to dig wells or dam rivers, we followed its paths to find food, shelter, and life and thus found the place to build our City in “green pastures” close to “still waters”: the ultimate home for most of our species. Water flows through our existence, cradling life from its first breath. As the universal solvent, it embraces all it touches, breaking boundaries and dissolving barriers in a dance that mirrors the alchemist’s sacred principle of “dissolve et coagula”, where the cycles of water lead to creation and union.

Today, in the 21st century, water continues to shape the world—but now, for most of us, hidden and “straightened out” beneath concrete, negotiated in international treaties, mixed up with all of our “commodities”, goods and resources, and often carelessly contaminated by economic or health choices, and climate crises.

And yet, it remains the invisible thread that stitches together territories—connecting us as “urbanite consumers” to the farmer who plants, and the ESG analyst to the riverside woman carrying a bucket of water, or the favela resident dependent on water trucks to the investor in the water sector in aircon offices in the Big City. Water―a resource, a symbol for its fluidity, a right not always given, and also a strategy—is at the core of a new territorial economy, where the governance of resources, carbon, biodiversity, and capital, labor, goods, and services are not isolated concepts but components of the same equation. Let us try to learn from the wise courses it takes from clouds to mountains to sea…

Water is both a natural phenomenon and a striking everyday political reality. A source of life and, increasingly, a source of tension. In Brazil, in Africa, or in the Middle East, and around the world, water governance has evolved from a technical debate into a geopolitical, environmental, economic, and cultural arena. It is no longer just about supplying our cities or irrigating crops; it is about understanding water as living infrastructure, a foundational element of a new landscape paradigm that integrates production, conservation, and personal pertinence to a territory. Water is “the life behind all products”.

In this essay, we explore water also as a factor of systemic integration, linking urban and rural areas, consumption and production policies, and the care of capital and the commons, making us as individual “urbanites” rethink our everyday actions as a collective whole.

“Nothing is softer or more flexible than water, yet nothing can resist it.” – Lao Tzu

Brazil: A hydropowerhouse in conflict with its own territories

With 12% of the world’s available surface freshwater and the largest river network on the planet, Brazil should be a global leader in water security and sustainable territorial development (ANA, 2023; IBGE, 2021). With over 85% of its population in cities, and with the largest conurbations in the Southern part of the continent, Brazil’s 5,565 municipalities, including Belem, the upcoming host of the Climate COP 30, should be champions in water-related and nature-based solutions. However, this abundance masks an unequal distribution, both geographically and socially. The North region holds over 70% of the country’s water resources but is home to only 7% of the Brazilian population (IBGE, 2021). Meanwhile, regions like the semi-arid Northeast face chronic water scarcity, directly affecting agriculture, public health, and rural livelihoods.

While a cursory check could indicate that Brazil is a water country, desertification already affects 13% of Brazil’s cities, threatening productive and biodiverse areas in biomes such as the Caatinga, worsened by unsustainable agricultural practices, improper water use, and climate change. The Amazon, arguably the largest water basin globally, is already affected by lack of potable water, wildfires, and drought, but this also strikes, through rivers in the sky, the overdeveloped conurbations around Sao Paulo, Salvador, Rio, and the steeply growing cities in the South (MMA, 2024), who quite literally can smell the smoke and witness the haze thousands of kilometers away. Unplanned urbanization also compromises strategic water sources and increases soil impermeabilization, intensifying floods, shortages, and pollution—as seen in the basins of the Tietê, Capibaribe, Parana, Iguaçu, and Amazon rivers.

This paradox demands more than just supply policies: it requires new territorial intelligence—of a fluid and adjusting kind. As the Brazilian expert, José Galizia Tundisi (2010) stated, “Water resource management is, above all, a matter of knowledge, planning, and integration”. It may also be a proxy for resource management capacity overall, and we need to make its wise long-term goals a crucial issue when hosting climate COP 30 in November 2025.

Water, carbon, and landscape, the “Rio resilience” triad for a water country

The economic and social relationships between water, climate change, nature, and landscape are circular and cumulative across the urban-rural divide. Urban and peri-urban water-based ecosystems such as mangroves, flooded forests, peatlands, and wetlands can capture vast amounts of carbon—up to ten times more than tropical forests per unit area (IPCC, 2021). Their degradation turns them into net sources of greenhouse gases, undermining territorial resilience and water security—very often linked to the degradation of quality of life, revenue, and employment of residents and stewards.

If this is true everywhere, it rings ever more urgent in Brazil, where an estimated 35% of mangroves have already been degraded or replaced by urban developments, ports, and shrimp farming (MMA, 2024). The Amazon’s blue zones, which function as “aquatic lungs”, are threatened by fires, illegal drainage, and deforestation for extensive cattle ranching. This collapse is exacerbated by the lack of integration between land use policies, water resource management, urban planning, biodiversity conservation, and climate mitigation. Brazil is a signatory of the Ramsar Convention (1993) and the original venue of the three Rio Conventions (Climate, Biological Diversity, and Desertification), yet urban and rural planning instruments largely remain fragmented, limiting the effectiveness of environmental public policies (RAMSAR, 2024). However, encouraging signs are coming up.

Among the leading initiatives in sustainable urban development, the “Programa Cidades Verdes Resilientes” (Green Resilient Cities’ Program, PCVR), created in 2024 and coordinated by the Ministries of Environment and Climate Change, Cities, and Science, Technology, and Innovation, integrates urban, environmental, and climate policies to promote sustainable practices and value urban green spaces. The AdaptaCidades initiative provides a useful complement, by bolstering adaptation and resilience strategies and working with local governments in crafting municipal or regional adaptation plans and towards a level of “climate federalism” as outlined in the recently adopted Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and the recently enacted 14.904/2024 law setting guidelines for adaptation plans.

At the subnational level, Paraná State has emerged as a pioneer in biodiversity conservation through innovative financial mechanisms and becoming the first subnational government in the country to implement a biodiversity credit policy aimed at offsetting the environmental impacts of industrial activities. Developed in collaboration with the LIFE―Life Business and Biodiversity Coalition, it already targets 25 Private Natural Heritage Reserves (RPPNs) within the state―it will certainly be replicated elsewhere. Our cities and States have solutions, and we cannot afford the luxury of keeping solutions to ourselves. Coordinated decentralized cooperation is not new but can be scaled up geometrically through incentives―every multilateral development bank, as well as most bilaterals today have a green cities program.

We, urbanites: not guilty, but co-responsible; let’s get busy!

Our concept of “urbanite” is affectionate—as Pogo notably said, “I’ve seen the enemy, and he is us”. We are city-dwellers who, though physically distant from nature, seek to reconnect with it through conscious practices: responsible consumption, organic food, active mobility, green architecture, engaged art, and climate or nature activism. Yet, as individuals we are embedded in a web of material and symbolic flows we often do not recognize because we were trained not to. What seems like a simple act—buying an agroecological product, choosing a B Corp brand, or visiting an urban park—can trigger large-scale economic and ecological circuits involving entire watersheds, production chains, and rural territories. We are just getting the technological tools and awareness to measure and manage these urban-rural linkages, these “butterfly effect” elements in economic territorial policy. And many of our city and State elected officers and public officials have read the writing on the wall for urban Nature-based Solutions, those co-benefits we get from doing things a bit differently, particularly for water security and health. The new ways emerge from the crisis of old ways.

You, dear urbanite, may have never seen an aquifer, never stepped into a spring, or had the patience to hear the sound of a stream outside on a weekend hiking trail―or even felt the need to. Yet still, your life is immersed in water, from 65% of your body composition to 71% of the Earth’s surface covered by it (Guyton et al, 2017; FAO, 2021). Every item in your diet, every product from your online store, every video game you play, even every bitcoin you mine or buy, was produced, transported, reassembled, distributed, and sold somewhere where water—and those who care for it—played a crucial role. Once you know that, you can’t “un-know”.

The countryside can feed the city, the city can finance a healthy countryside, and both can enjoy the benefits of protected areas―but this equation is not working yet. Choices in modes and technologies of rural production are still treated as peripheral by us as “urbanites”, despite ensuring metropolitan food, climate, and water security. The financial flows originating in the city do not always―or even regularly―return equitably to encourage solutions in rural areas. We need―and we already have the basic elements of―a logic of territorial reciprocity: water, food, biodiversity, and ecosystem services come from the countryside; support for the right kind of choices on knowledge, technology, and investment can (and should) come from the city.

The transition towards this virtuous urban-rural, nature-based cycle, for which we already have enough practical cases all over the world, can only be completed if we recognize, upfront, that adjusting to change requires movement, the departure from comfortable ways. Sustainability has seed investments and maintenance costs—and these must be incorporated into our accounting, by design, from inception and through investments, into every urban green infrastructure, fair production chains, and all our public policies, integrating our stewardship of both urban and rural areas.

From concept to practice: Instituto Orizzonte and the flows of governance

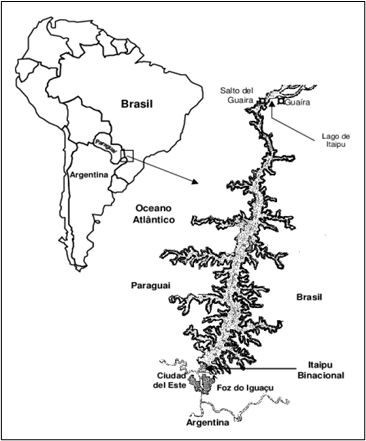

Founded in 2023, Instituto Orizzonte was born from the recognition that sustainable development depends on intelligent territorial governance based on technical knowledge, institutional coordination, and socio-environmental justice. Our founding work with Itaipu Binacional and the 16 municipalities bordering the Itaipu Lake is an example of how water can be revalued as a pillar of planning and municipal and regional integration (ITAIPU BINACIONAL, 2024).

Our institute’s assessment of the lake’s nautical potential goes beyond tourism: it considers water as an ecological and cultural infrastructure capable of simultaneously generating economic development, leisure, identity, and environmental conservation. Our approach attempted to combine technical data, social participation, and institutional innovation, aligning objectives such as the UN’s SDGs 6 (water and sanitation), SDG 11 (sustainable cities), SDG 12 (responsible consumption), SDG 13 (climate action), 14 (Life on water), and 15 (Life on land) with real territorial strategies anchored in multilevel public policies and partnerships (SDG 17).

Water as a language to speak “landscapese”

Ultimately, water is a common language. Its care speaks to everyone: Indigenous peoples and technocrats, farmers and urban planners, scientists and poets. By recognizing it as a link between natural and social systems, we at Instituto Orizzonte aim to build truly integrated territorial governance, capable of addressing 21st-century challenges with justice, efficiency, and beauty.

But this transition requires political courage, economic investment, and cultural engagement. It is not just about “preserving water” but about reshaping how we live with it. For this, urbanites, policymakers, artists, and farmers must converse—and water is where this conversation can begin.

The good news? You, dear urbanite, and Brazil’s cities, have already started, and you can help just through small changes in your choices. The water that reaches your faucet has passed through a watershed, traveled through soil and forests, and certainly crossed political borders. Understanding this means placing yourself as an urban actor within the territory. More than that, it means realizing that we are not isolated in an urban bubble but are part of a larger system that needs us to function better in our everyday choices. Consider the flows of water—what do they teach us? How can we support its natural flow better through our choices every day?

By seeking sustainable alternatives constantly, supporting conscious practices better every day, and gradually realizing how water, climate, and biodiversity are part of most commercial transactions and exchanges with people, you are already part of the change. What we propose here is to go further: to connect these personal actions with collective, systemic, and integrated efforts.

Because, in the end, living green and being mindful of the remote and rural impacts of our green urban living are more than just trends. They are political and ethical emergencies, and also our daily choices. And water—this silent presence that inhabits our bodies, landscapes, and cultures and inspires our work—may be the best guide on this journey. Please reach out to us if you agree and want to contribute to these goals.

Oliver Hillel and Wythaker Abreu

Montreal and Curitiba

References

ANA. Bacias hidrográficas do Brasil. Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico, 2023. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/ana/pt-br/assuntos/bacias. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

BRASIL. Plano Nacional de Segurança Hídrica. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Regional, Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico, 2024. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/ana/pt-br/assuntos/seguranca-hidrica. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

FAO – FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS. The state of the world’s land and water resources for food and agriculture (SOLAW). Rome: FAO, 2021. Disponível em: https://www.fao.org. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

Guyton, A. C.; Hall, J. E. Tratado de fisiologia médica. 13. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2017.

IBGE. Malha hidrográfica brasileira. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2021. Disponível em: https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/informacoes-ambientais/15794-hidrografia.html. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

IPCC. Relatório Especial sobre Mudanças Climáticas e Água. Painel Intergovernamental sobre Mudanças Climáticas, 2021. Disponível em: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/special-report-on-climate-change-and-water/. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

ITAIPU BINACIONAL. A Usina. Disponível em: https://www.itaipu.gov.br/a-usina. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

MMA. Painel Brasileiro de Desertificação e Degradação da Terra. Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima, 2024. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/mma/pt-br. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

RAMSAR. Ramsar Sites Information Service. Secretaria da Convenção de Ramsar, 2024. Disponível em: https://rsis.ramsar.org/. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

UNESCO. Relatório Mundial das Nações Unidas sobre o Desenvolvimento dos Recursos Hídricos. Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura, 2019. Disponível em: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367308. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

WORLD BANK. Water Security and Climate Resilience. Banco Mundial, 2021. Disponível em: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water/publication/water-security-and-climate-resilience. Acesso em: 24 Mar. 2025.

Leave a Reply