about the writer

Gitty Korsuize

Gitty Korsuize works as an independent urban ecologist. She lives in the city of Utrecht. Gitty connects people with nature, nature with people and people with an interest in nature with each other.

Introduction

This roundtable wants to shine a light on the habitat night from different perspectives and different parts of the globe.

Natural darkness isn’t merely a time of day. For countless extraordinary species, it’s home. When the sun sets, things start to get interesting among wild animals. Wherever we live, whether in the city suburbs, or country, darkness conjures a hidden world of wildlife that most of us rarely glimpse. Foxes, wolves, and bears prowl while skunks, opossums, and porcupines lurk; fireflies send flashing signals to potential mates; raccoons rummage for food; owls and bats fly overhead. Night is not just a time, but a diverse habitat we know little about.

This roundtable wants to shine a light on the habitat night from different perspectives and different parts of the globe. It aims to take readers on a journey to discover the secret city nightlife around the world. During the Nature of Cities Festival 2024, in Berlin, this field trip to a Berlin cemetery brought people and nocturnal wildlife together. There was also a moment to connect with and experience the dark. Back then, the book by Sophia Kimmig was only available in German. In 2025, we welcome the English version.

Read the book excerpt by Sophia Kimmig here.

about the writer

Niels de Zwarte

Niels de Zwarte is the head of Bureau Stadsnatuur (Urban Ecology Research Department) and deputy director of the Natural History Museum Rotterdam. He is an ecological consultant involved in a wide range of projects for governments and companies in the Netherlands, focusing on urban biodiversity monitoring and advising on spatial planning, nature-inclusive management, and policy.

Niels de Zwarte

De stad is geen exclusief domein van de mens. De nacht is geen niemandsland tussen twee werkdagen. Ze is een gedeelde ruimte. Willen we biodiversiteit behouden, dan moeten we de nacht opnieuw leren waarderen.

Stad in het donker: gedeelde ruimte na zonsondergang

Read in English.

Het is duidelijk welke soort de keystone species is in de stad: de mens. Geen andere soort in dit relatief jonge ecosysteem drukt zo’n dominante stempel op zijn leefomgeving en de processen daarin. Door die dominantie vergeten mensen vaak dat we onze buitenruimte delen met duizenden soorten dieren en planten. We delen niet alleen de publieke buitenruimte, we delen zelfs onze huizen. Ook in de stad. Ook in de nacht.

Wanneer de zon ondergaat en mensen zich terugtrekken, komt de stad op een heel andere manier tot leven. De donkere uren vormen geen leegte of pauze tot het weer licht wordt. Voor veel nachtdieren begint juist dan hun actieve deel van de dag. Denk aan egels, uilen, nachtvlinders en zeker ook aan vleermuizen. In Europese steden kun je ongeveer een tiental soorten vleermuizen tegenkomen, waaronder de gewone, ruige of kleine dwergvleermuis (Pipistrellus pipistrellus, P. nathusii, P. pygmaeus) en de laatvlieger (Eptesicus serotinus). Ze jagen op insecten boven vijvers en in tuinen, volgen boomrijen tussen flats en vinden hun verblijfplaatsen in gebouwen. Ze slapen, overwinteren, paren of brengen hun jongen groot op kerkzolders, achter gevelbetimmering, onder dakpannen of in de spouwmuur. Vleermuizen zijn echt fascinerend. Ze zijn de enige zoogdieren op aarde die actief kunnen vliegen en gebruiken echolocatie om te jagen en zich te oriënteren. Dankzij hun winterslaap en efficiënte DNA-herstelmechanisme worden ze uitzonderlijk oud voor hun formaat.

De co-existentie met wilde dieren in de stad is waardevol. Niet alleen functioneel (vleermuizen eten veel insecten, helaas minder steekmuggen dan vaak wordt geschreven in populaire artikelen), maar vooral intrinsiek. De waarde van een dier afmeten aan zijn nut voor de mens getuigt van een antropocentrische blik. Als sleutelsoort van de stad zouden wij juist moeten leren om de waarde van wilde dieren en planten op zichzelf te zien. Wij zijn onderdeel van de biodiversiteit, niet het middelpunt ervan.

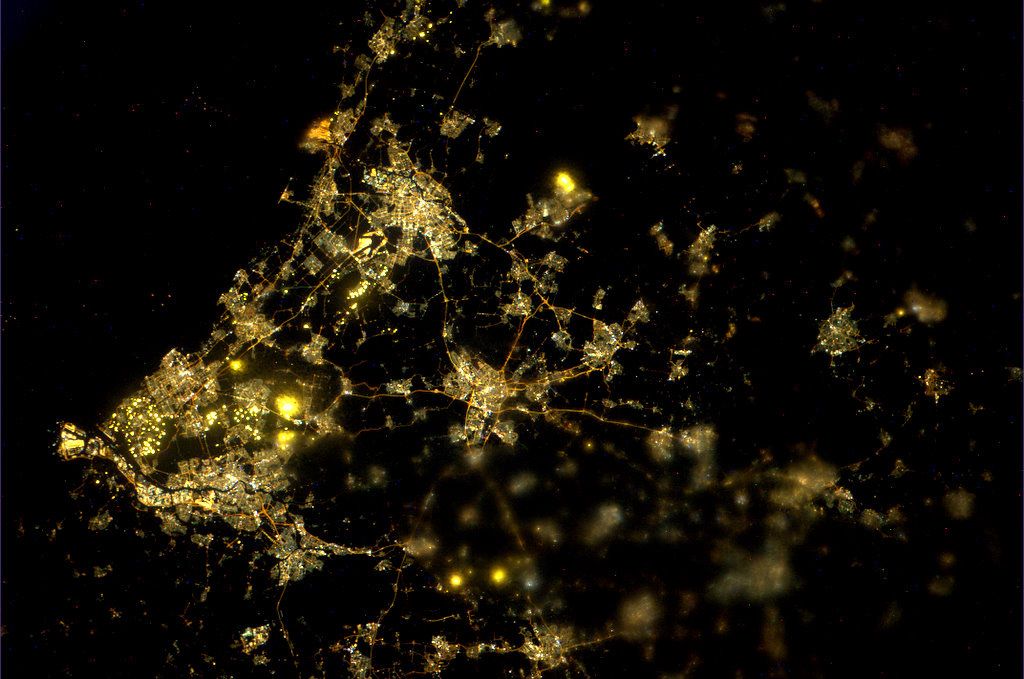

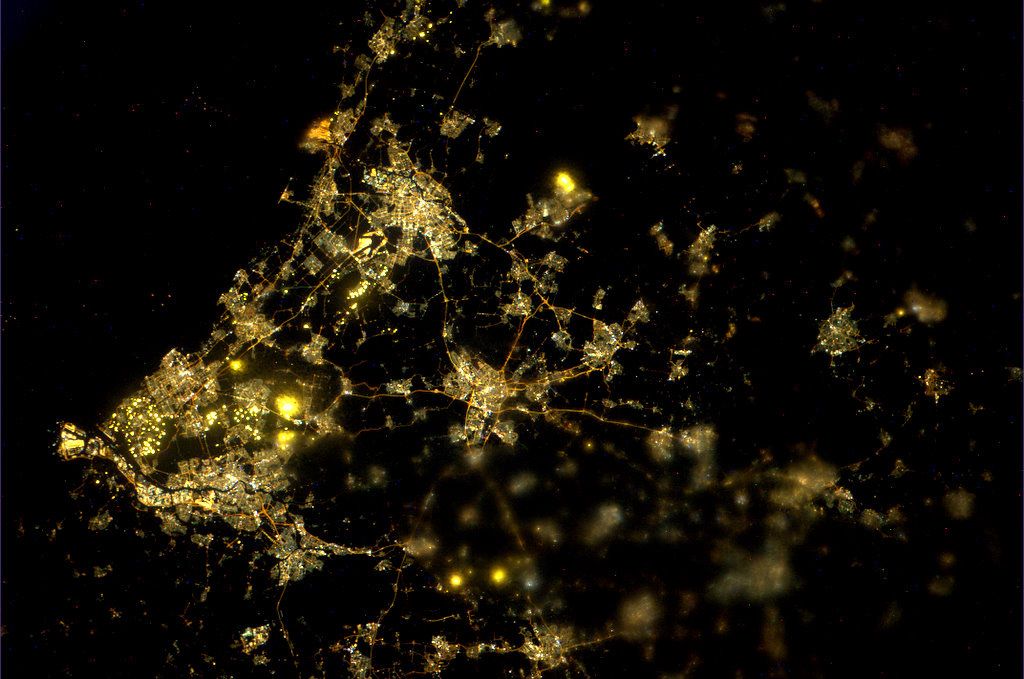

Tegelijk verandert het nachtleven razendsnel. Waar natuurlijke duisternis ooit vanzelfsprekend was, is ze in steden grotendeels verdwenen. Kunstlicht was ooit schaars en kostbaar, maar met de introductie van elektrische straatverlichting vanaf begin 1900, en sinds 2000 vooral ledverlichting, is licht alomtegenwoordig. Ironisch genoeg heeft die efficiëntie van led geleid tot méér licht, niet minder. Wereldwijd neemt nachtelijke kunstverlichting (ook wel ALAN genoemd: artificial light at night) jaarlijks met een verontrustende 2–6% toe. In grote delen van West-Europa is de Melkweg inmiddels niet meer zichtbaar. De stedelijke hemel wordt steeds blauwer door de korte golflengtes van witte leds die rijk zijn aan UV, waarop veel dieren sterk reageren.

Nog een voorbeeld: de lichtsterkte op Nederlandse parkeerterreinen en bedrijventerreinen is vaak 20–50 lux – overeenkomend met 2.000 tot 5.000 lumen per vierkante meter. Dat is veel meer dan nodig is voor veiligheid of zicht. Voor veel vleermuizen betekent dit dat zij routes, drinkplaatsen en jachtgebieden mijden. Insecten worden massaal aangetrokken door lampen, raken uitgeput, sterven, en verdwijnen uit de voedselketen. Ook mensen ervaren negatieve effecten: verstoorde slaap, verhoogde stress en het verlies van sterrenlicht.

Gelukkig ontstaan er hoopvolle tegenbewegingen. In steden als Den Haag, Ljubljana en Bonn zijn zones ingesteld waar de nacht weer donker mag zijn: ‘donkere ecologische corridors’ zonder straatverlichting of met dynamische of aangepaste amberkleurige lampen. Deze verlichting houdt rekening met zowel menselijke veiligheid als ecologische behoeften. Zulke initiatieven tonen dat biodiversiteit en stedelijk leven hand in hand kunnen gaan – mits we ook donkerte in de nacht erkennen als een belangrijke levensbehoefte.

De stad is geen exclusief domein van de mens. De nacht is geen niemandsland tussen twee werkdagen. Ze is een gedeelde ruimte. Willen we biodiversiteit behouden, dan moeten we de nacht opnieuw leren waarderen. Laten we beleid maken dat ruimte biedt aan stilte en duisternis – in het belang van zowel mens als dier. Want samen leven we in de stad. Dag én nacht.

The city is not ours alone. The night is not a void between workdays. It is a shared space. If we want to preserve urban biodiversity, we need to learn to value the night again.

Urban darkness: a shared space after dusk

It’s clear which species is the keystone species in the city: humans. No other species in this relatively young ecosystem leaves such a dominant mark on its surroundings and the processes that shape them. Because of that dominance, we easily forget that we share our outdoor spaces with thousands of other species, wild plants, and animals alike. We don’t just share public green areas; we even share our homes. In the city. Even at night.

When the sun sets and people retreat indoors, the city comes alive in a completely different way. The dark hours are not a pause or void before daylight returns—they are, for many nocturnal species, the true beginning of their day. Think of hedgehogs, owls, moths, and especially bats. In European cities, you can encounter around ten bat species, including the common, Nathusius’, and soprano pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus, P. nathusii, P. pygmaeus) as well as the serotine bat (Eptesicus serotinus). They hunt insects above ponds and gardens, navigate tree-lined avenues between apartment blocks, and roost in our buildings. They sleep, hibernate, mate, or raise their young in church attics, behind façades, under roof tiles, or inside cavity walls.

Bats are truly fascinating. They’re the only mammals capable of true flight and use echolocation to hunt and orient themselves. Thanks to their ability to hibernate and an efficient DNA repair system, they can live remarkably long lives for such small mammals.

Our coexistence with wildlife in cities is valuable—not only functionally (bats eat a lot of insects, though fewer mosquitoes than popular articles often claim), but especially intrinsically. Measuring a species’ worth by how useful it is to us reflects a deeply anthropocentric view. As the dominant species in the urban ecosystem, we should learn to see wild plants and animals as valuable in their own right. We are part of urban biodiversity—not its center.

At the same time, urban nightscapes are changing rapidly. Where natural darkness was once a given, it has now almost vanished from city life. Artificial light was once rare and expensive, but with the introduction of electric streetlights in the early 1900s—and since 2000, a rapid rise in LED lighting—light is now everywhere. Ironically, LED’s efficiency has led to more lighting, not less. Globally, artificial light at night (ALAN) is increasing by an alarming 2–6% per year. In much of Western Europe, the Milky Way is no longer visible. Urban night skies are increasingly blue due to the short wavelengths and UV-rich spectrum of white LEDs—something to which many animals are particularly sensitive.

One striking example: on Dutch industrial estates and parking lots, light levels often reach 20–50 lux—equivalent to 2,000 to 5,000 lumens per square meter. That’s far more than needed for safety or visibility. For many bat species, this level of brightness means avoiding vital routes, drinking sites, and foraging areas. Insects are drawn in large numbers to lamps, where they exhaust themselves, die, and drop out of the food chain. People, too, suffer from disrupted sleep, increased stress, and the loss of natural darkness.

Thankfully, hopeful counter-movements are emerging. In cities like The Hague, Ljubljana, and Bonn, zones have been created where darkness is preserved: “dark ecological corridors” with no streetlights, or with dynamic, low-intensity amber lighting that responds to both human use and ecological needs. These initiatives show that urban life and biodiversity can go hand in hand—if we recognize darkness as a vital element of our shared habitat.

The city is not ours alone. The night is not a void between workdays. It is a shared space. If we want to preserve urban biodiversity, we need to learn to value the night again. Let’s shape policies that allow for silence and darkness—for the wellbeing of both people and wildlife. After all, we live in the city together. Day and night.

about the writer

Gitty Korsuize

Gitty Korsuize works as an independent urban ecologist. She lives in the city of Utrecht. Gitty connects people with nature, nature with people and people with an interest in nature with each other.

Gitty Korsuize

Let’s declare cemeteries as protected nocturnal habitats and build on connecting them with dark corridors throughout our city and to the natural areas surrounding our city. A fourth-dimensional ecological corridor that only will be (un)visible during the night.

Let’s design our cities in 4D!

We think of our world in 3D, but the book The Living Night shows us that we should add a fourth dimension to our perspective: time. There is a whole new world we know little about which we should add to our daily lives, into our research, and into our project designs.

What we do in our daily world impacts the habitat night. Often we do not think about the consequences. Putting fences around your garden will decline the feeding grounds of the hedgehog, by reducing the bushes in our parks we also reduce the cover on routes of a weasel, lightning poles in the streets make moths infertile and if the light also illuminates the waterways along the road, certain bat species will shy away from hunting for insects above these waters. Even in our quest for reducing our carbon footprint the effects on the habitat night are “visible”; wind turbines are put on (night-time) migration routes of birds and bats, cavity walls are filled with isolation materials thus making them unavailable as roosting places for bats (or worse, killing the bats by entrapment) and fields of solar panels reduce the hunting grounds of owls.

If we want to reduce the negative impacts on habitat night, the first quest should be raising public awareness on the nocturnal wildlife that can be found in their city or even their garden. By writing articles, giving excursions, sharing videos of nocturnal wildlife on social media, and daytime events and evening excursions adjoining “national moth night” or “international bat night”.

Citizen science initiatives also contribute to more awareness. Just some examples of possible initiatives: in the Netherlands different monitoring scheme allow citizens to investigate the nocturnal wildlife: they can investigate their own garden during the night with wildlife cameras or place a Moth LED trap in their garden or on their balcony. In London, you can contribute to the night watch survey or join the British Bat Survey (BBatS).

We can also attract more attention to the needs of our nocturnal inhabitants by making their needs more visible: fences with colourful hedgehog gateways, buildings with visible roosting boxes for bats, or hanging bat boxes in the trees in our parks. By using ember coloured light in our lighting poles we can reduce the negative impact on some nocturnal species.

But sometimes we do protect the habitat at night, albeit unintentionally: in Utrecht some parks are closed from sunset until dawn, as are our graveyards. No lightning is needed for social safety and thus making it a dark and undisturbed place for habitat night to come to life. Let’s declare cemeteries protected nocturnal habitats and build on connecting them with dark corridors throughout our city and to the natural areas surrounding our city. A fourth-dimensional ecological corridor that only will be (un)visible during the night.

about the writer

Eric Sanderson

Eric Sanderson is Vice President for Urban Conservation at the New York Botanical Garden, and the author of Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City. His upcoming book, Before New York: An Atlas and Gazetteer, will be released in 2026.

Eric Sanderson

What do we miss not seeing the stars above our cities? The vast everything cast in inscrutable symbols and cosmic histories; pinpricks of light―of hope, of resistance―shining out of the universal night.

Xinkw nëwëmi (The Vast Everything)

What do we miss when we can’t see the stars above us? As Indigenous people of the landscape that became New York City might have said, xinkw nëwëmi, the vast everything. Everything that became the landscape that became the city, including you and me and the shiny photons emitted from your screen, and the energy required for your fingers to click away, began with events some 13.7 billion years ago when the universe suddenly, and for its own reasons, sprang into being: the so-called Big Bang. Everything since―the moon, the stars, the Earth, your city, my city, you and me―is just an elaboration of those primordial potentials into forms and the inherent and resistance of those forms to the inevitable dissolution into a low, universal hum.

What would one see? I like to imagine the evening of September 11, 1609, on the eve of New York’s colonization, by all accounts a clear, cloud-free day, when climbing a tree in lower Mannahatta or paddling out among the waves in the most beautiful harbor of the world, one could turn one’s face upward to see the events of the great beginning. Astronomers tell us that some 300-400 million years after the Big Bang, the first stars collected enough mass to ignite on the distant horizon, and the first stars flamed into being. Stars like people burn, grow, and die, and collections of those stars, and their children and grandchildren, aggregated to form our galaxy when the universe was about 8.7 billion years old. Out on one arm of the many-armed spiral galaxy (the Milky Way), our solar system would eventually coalesce, a tiny instance of the universal story.

Our Sun, a star, caught flame around 4.5 billion years ago. The Earth at your feet formed from dust too far out to get sucked into the Sun, but too close to fly away. Ours is the fortunate planet, near enough to receive enough warmth that water is liquid on the surface, but not so much warmth that all water boils away. The first billion years after formation were rough going, with multiple meteor strikes, massive volcanoes, molten seas, and little to no atmosphere. The Moon is thought to be a chunk of the Earth disgorged after one such massive collision. Such collisions gave the Earth a tilt that gives us seasons. The pull of the Moon generates the tides. The heat of the furious bombardments of the early days remains trapped inside the planet’s core, where it generates a protective magnetic field, causes slight but significant wobbles in the Earth’s orbit that change the climate, fuels volcanoes, and enables plate tectonics. The land, the water, and the sky on the surface reflect in ways both large and small what is happening deep inside.

One of the more curious consequences of the random bumps and accidents of the physical universe is the generation of life. On Earth, life emerged around 3.7 billion years ago, possibly earlier, possibly multiple times, which suggests it also failed multiple times. The evolution of photosynthesis by cyanobacteria resulted in a waste product, oxygen gas. The Great Oxidation Event of 2.4 billion years ago set the stage for eukaryotic life (cells with substructures called organelles) using aerobic respiration which evolved around 1.85 billion years ago. Multi-cellular organisms are about 1.7 billion years old; plants, which evolved from green algae, are about one billion years old; the earliest animals, sponges, and comb jellies are about 750 million years old; the first vertebrates (fish) about 480 million years old; the earliest land plants about 470 million years old; the earliest Humans (Homo sapiens), our ancestors, differentiated from their hominin kin only about 300,000―400,000 years ago. It was only a mere 80,000 years ago that they left Africa to wander the rest of the continents. Only 10,000 years ago (give or take), did people arrive in Welikia (my name for the landscape before New York City), around the same time first proto-cities were developing near the early agriculture fields half a world away.

What do we miss not seeing the stars above our cities? The vast everything cast in inscrutable symbols and cosmic histories; pinpricks of light―of hope, of resistance―shining out of the universal night.

about the writer

Madhusudan Katti

Madhusudan is the Director of Science, Technology, and Society, and Associate Professor of Public Science in the Department of Integrative Humanities and Social Sciences at North Carolina State University.

Madhusudan Katti

Can we turn off or at least dim all these city lights, please? As much for our fellow nonhuman citizens as for our own souls that also evolved to rest at night, looking up into the dark sky pondering our existence.

What shall I tell the Dung Beetles who ask why we hid their Milky Way?

I became a stargazer before I was a birdwatcher, learning to build telescopes and point binoculars high up to spot this comet or that distant galaxy hidden beyond Mumbai’s light dome, years before pointing them into some tree’s canopy in the day to spot birds. Before birds hooked me, I was awestruck by Flying Foxes, giant fruit bats that took wing in the twilight, emerging from their roosts to take over my hometown, India’s Gotham City searching for the myriad figs and other fruiting trees lining Mumbai’s parks and streets.

My obsession with birds amplified my stargazer’s longing for clear dark skies where one could see the Milky Way. I fled the city for a while and went deep into the jungles of southern India to study migratory warblers. There, when waking up at dawn to catch birds, I met another creature of the night, a tiny primate named the Slender Loris, endemic to that region. I learned how important darkness was to both types of creatures: one undertook long nocturnal flights between breeding and wintering grounds while the other shied away even from moonlight.

Just as astronomers fretted about being able to observe distant galaxies to uncover the secrets of the early universe amid the ever-growing glow of city lights everywhere, wildlife biologists also worried about what so much light was doing to all the species that loved the dark but had no say in the matter as humanity sought to banish the night.

Now I am back to living in a city, teaching urban wildlife ecology, and joining my birder comrades in urging cities to turn down the lights at least for a few weeks every Fall and Spring when billions of birds migrate, most flying right over our heads through the night. Bright city lights are a real and present danger because they confuse and disorient birds whose navigational apparatus evolved in the pre-urban dark age. Likewise, I have friends who patrol tropical beaches at night to protect sea turtles that crawl out of the ocean annually to nest along the shore; their hatchlings also get confused by well-lit urban shores because they evolved to find the sea by seeking the lighter sky over the ocean, not land.

Urban light continues to ruin the essential magic of night, yet many creatures are adapting to city life. Even the slender loris can be seen in cities like Bengaluru, where I’ve spotted them sneaking through the tree canopy, right over the heads of oblivious humans afraid of the dark.

One lowly species I find kinship with is the Dung Beetle, who got that name for rolling up the dung of large herbivores into balls in which to lay eggs. Surprisingly, these busy little scavengers who keep us from drowning in a sea of dung actually look up to the sky and use the Milky Way to keep themselves oriented at night while scuttling backward with their precious dungballs. Who would’ve thought? But what of dung beetles that now find themselves surrounded by disorienting urban lights? They latch on to some bright light and end up going in less hospitable directions in the treacherous urban landscape. Just like the turtles who can’t find the ocean, and the birds that fly into brightly lit buildings.

Can we turn off or at least dim all these city lights, please? As much for our fellow nonhuman citizens as for our own souls that also evolved to rest at night, looking up into the dark sky pondering our existence. What shall I tell the dung beetles when they ask why we hid their Milky Way?

about the writer

Mara Cotterink

Mara works as a science communicator at the BioClock Consortium. She bridges science and society by translating research on biological rhythms—of humans and all life on Earth—into accessible stories. Her work highlights the relevance of circadian health and the natural rhythm of life in shaping a more balanced world.

Mara Cotterink

What if we embraced darkness as a shared ecological space? What if urban lighting policies would not only acknowledge human needs but also the nocturnal lives of many other species unfolding around us?

The Unbearable Brightness of the Dark

For billions of years, life on Earth has evolved under the steady rhythm of day and night. This cycle of light and dark is one of the most ancient and universal environmental signals — a daily cue that has shaped the behaviour, physiology, and timing systems of all living organisms.

Some species adapted to darkness to avoid predators; others evolved to take advantage of daylight for foraging or mating. Temperature also played a key role: early mammals, for example, became nocturnal to avoid daytime predators like dinosaurs. Because mammals could regulate their body temperature, they were able to remain active during the cooler nights. Reptiles, on the other hand, rely on external heat and typically need sunlight to warm up before they can move efficiently. Plants, too, anticipate and respond to the light-dark cycle: some open their flowers only at dawn, while others bloom at dusk to attract nocturnal pollinators. This temporal partitioning reduces competition. Even trees use changing day lengths to know when to grow or shed their leaves.

But in just over a century — an evolutionary blink — humans have transformed the night. The invention of artificial lighting has allowed us to extend our activity into nighttime hours, pushing the boundaries of the natural day-night cycle, even though our biological clocks remain closely tied to it. Cities now glow deep into the night, enabling 24/7 economies, social lives, and transportation systems. Light has become synonymous with progress, safety, and prosperity.

Yet this brightness comes at a cost. Our internal biological clock with its 24-hour cycle (circadian rhythm) depends on natural light cues to regulate sleep, metabolism, hormone release, and immune function. Exposure to artificial light at night disrupts these natural clocks. Melatonin secretion, essential for the onset of sleep and nighttime restoration, is delayed. As a result, people may feel tired but find it hard to fall asleep. Over time, chronic circadian disruption increases the risk of sleep disorders, depression, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.

Humans are not alone in this. Light pollution affects virtually all other species. Nocturnal animals may change their hunting or mating behaviors; migratory birds become disoriented; trees near streetlamps may keep their leaves longer, misreading the seasons. Darkness is not just the absence of light — it is a habitat, a condition many organisms depend on to survive and thrive.

In our cities, the night is becoming a lost landscape. Instead of preserving the natural rhythm of light and dark, we have overwritten it with constant illumination. But what if we embraced darkness as a shared ecological space? What if urban lighting policies would not only acknowledge human needs but also the nocturnal lives of many other species unfolding around us?

There is beauty and function in the dark. Moonlight, starlight, even the subtle glow of fireflies — these once defined the nighttime experience. By dimming our lights, we can restore not only the integrity of ecosystems, but also the visibility of the stars. And perhaps, rediscover a more humane pace of life.

Cities that respect the night — through thoughtful lighting, darker zones, and public awareness — can lead the way in restoring this hidden half of our environment. Less light does not mean less safety or prosperity; on the contrary, it can foster greater well-being, biodiversity, and even economic resilience. It’s about rebalancing our relationship with time, nature, and ourselves.

Within the BioClock Consortium, researchers and societal partners from across the Netherlands have joined forces to restore and preserve the health of the biological clock. The project covers the whole of society: from human health and disease to the natural environment and the protection of animals and insects.

Read more about our research and who we are at www.bioclockconsortium.org

Aliyu Barau

about the writer

Aliyu Barau

Professor Aliyu Barau is a trans-disciplinarian climate change expert and landscape ecologist. He is Geographer and Environmental Planner by training and research. Since 2021, he has been a Professor and subsequently Dean of the Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Bayero University Kano, Nigeria.

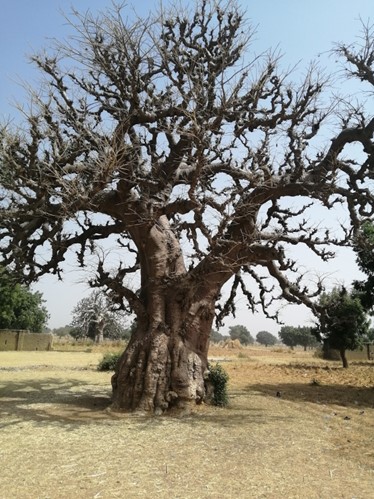

The Depreciation of vibrant night ecology in Kano, Northern Nigeria―A nostalgic sense

When we go to bed, the powerful night ecologies give us more wonders and fears.

My childhood memories of the night-time ecologies are very fascinating. All defined by nature―weather cycles more specifically. The composition of the ecosystem has changed completely in my adulthood―a more intensively lit city and the lost urban greenery and open spaces and architecture. What happens when the first rains drop? In that season, once the sun sets and light bulbs are put on, the bugs would come out en-masse and it is a time of play and joy as we come out to capture the flights of the bugs. Where there are no sufficient lights, the fireflies are most captivating as we had imagination and speculations on firefly engineering and biology wonders. We thought about a micromachine in their bellies in our children’s figment of the imagination. Towards the end of the rains come grasshoppers and locusts―our friends, patients, and specimens that we give surgical operations on their wings, bellies, and heads―we are doctors in the house.

When we go to bed, the powerful night ecologies give us more wonders and fears. Just before the rainy season, the weather would be very hot and hotter in the daytime. At nightfall, we would sit outside the room to take fresh air. When the national grid falls, we have better chances as we will do some astronomy by watching the stars that flicker in the sky and define their mythological meanings. Such sky-watching time could be interrupted by a near stampede scenario as we race to chase mice or rats that emerge from nowhere. Sometimes, it is costly when some scorpions leave their holes and hiding habitats and unleash their weapons, and they are not alone. Spiders, geckos, ants, and cockroaches are feared most by girls while boys try to kill them―a kind of an undying conflict. A ferocious dog barks from the back of the house, signaling the fear of thieves in the neighbourhood. We can distinguish that from normal time barking.

The cats’ fights or attacks on our hens are horrific nocturnal sounds or morning visuals experienced across seasons. Some mornings, we wake up to see what we cannot do with our trees is done very well by the bats and other nocturnal bats. While we cannot climb the top and delicate tree branches bats will do and will throw down half-eaten fruits. These fruits are forbidden for us as we cannot eat the food remnants of bats. The fruit bats that roam the night skies and feast on our trees’ fruits are basically two species―the bigger and smaller ones―Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera. As kids, we understand that both the former (called Jemage in Hausa) and the latter (called Birbiri) cannot fly again once they touch the ground. But we actually confuse the smaller ones for babies of the bigger ones. But in reality, we are afraid of them and can only use small sticks to flip them over and over and just observe. The brave among us lift them up and sometimes they fly and run away.

I am now nostalgic for those great nights of low lights and low noise. My children don’t experience much of sitting outdoors in the night. They don’t play much with insects as they see that as unhygienic. But they all read about fireflies in the storybooks. Why? Everywhere is more lit, and the light is undying because of the solar lights. The grounds are covered by tiles and the house is full of ornamental plants which is too bad for the nature at night.

Seema Mundoli and Harini Nagendra

about the writer

Seema Mundoli

Seema Mundoli is an Assistant Professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. Her recent co-authored books (with Harini Nagendra) include, “Cities and Canopies: Trees in Indian Cities” (Penguin India, 2019), “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) and the illustrated children’s book “So Many Leaves” (Pratham Books, 2020).

about the writer

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

Cities are no longer safe havens for these nocturnal species. As green and blue spaces disappear, destroyed by rapid urbanisation, the denizens of the night are struggling to survive.

Night is not just a time, but a diverse habitat we know little about. What is the nature of the dark hours in cities?

“Now Chil the Kite brings home the night

That Mang the Bat sets free—”

Thus begins the night song of the jungle in Rudyard Kipling’s “The Jungle Book”. Kipling may have written the poem keeping the jungles of Central India in mind, but even we ― who live in congested cities full of traffic ― are fortunate to witness the night that is brought in by the kite, and released by the bat. Nightlife, especially around green and blue spaces, can be quite diverse, no matter how urbanised a place is.

The metropolis of Bengaluru, south India’s information technology hub, is no exception. On evenings around water bodies such as Sankey Tank, we have witnessed black (Milvus migrans) and Brahminy (Haliastur indus) kites settling down at dusk to roost on the trees around the lake, while up in the sky thousands of bats fly from their roosting spots on Ficus trees in a nearby university campus, taking off to range across the city in search of food. Residents, returning home at dusk from work, can glimpse these bats.

Around the lakes of Bengaluru, a night walk in the monsoon is like walking into a wall of sound, a cacophony of frogs performing in an impromptu rock band concern. Bengaluru is also home to endangered and rare species such as the nocturnal slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus cabrera). A primate species, the loris is arboreal and sleeps during the day, active only in the night when it spends much of its life moving from one tree canopy to another, in search of food and a mate. They have a whistling call, and eyes that reflect the light of the torches used to spot them. Slender lorises feature in the cultural beliefs of city residents, especially the old-timers. Some believe that they are bad omens that bring death and misfortune, but others see them as bringing good luck, especially to children.

In Hyderabad, bat species dart among trees such as the Singapore cherry (Mutingia calabura), Indian mast (Monoon longifolium)and cluster fig (Ficus racemosa), feasting on the ripe fruits or snatching insects that are attracted to the streetlights. There are birds too, of many different kinds. The late-night peace of apartment complexes, where families are relaxing after a long day, can be shattered by the eerie screech of barn owls (Tyto alba). And in peri-urban layouts, where the city exists cheek-by-jowl with lakes and wetlands, we can still hear the “did-you-do-it” call of the red-wattled lapwing (Vanellus indicus), flapping its wings as it flies over an open field or grazing area, returning home in the late evening when dusk gives way to nightfall.

In the coastal city of Chennai, the night is the time when the female olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) sea turtles come to shore, laying their eggs on the beach. There are only seven species of sea turtles across the world. A fascinating feature about the olive ridley is that the females return to the very same beach to nest from where they hatched. While there are many theories as to how turtles return to their natal beaches, none have been proven yet. But because they come to the beaches at night, very few in the 12 million population of the metropolis of Chennai know about these fascinating and vulnerable species.

But cities are no longer safe havens for these nocturnal species. As green and blue spaces disappear, destroyed by rapid urbanisation, the denizens of the night are struggling to survive. The slender loris of Bengaluru needs overlapping tree canopies, so that it can jump from the branches of one tree to another, moving across the city in search of food, mates, and nesting spots. As trees are cut down for road widening and to build flyovers, the tree canopy that is critical to their survival is being fragmented. The lakes of Hyderabad are being ‘restored’ by cementing the mud banks, destroying the habitat for reptiles and amphibian species. The sea turtle hatchlings in Chennai are drawn away from their destination by the bright lights from the city—away from the ocean towards their death.

A city is, of course, home to humans. But it is also home to non-human species, and we need to prioritise their protection for the ecological, social, and cultural relevance of these species in our lives. And there are initiatives that give us hope. In Bengaluru, citizen science initiatives, such as the Urban Slender Loris Project, helped to raise awareness about this reclusive species, and the need to protect the avenue trees and wooded patches that constitute their primary habitat. Similarly, the Student Sea Turtle Conservation Network (SSTCN), which began in the 1970s, has conducted turtle walks along the beach to monitor egg laying by females, relocating nests to a hatchery where the eggs have a better chance of survival. The turtle walks draw in people from Chennai and across the country, volunteers who participate in this effort to create awareness and protect sea turtles.

Our cities may not be as rich in biodiversity as the jungles of Kipling’s books. But they need to be more than “concrete jungles” ― a reference to the many unpleasant aspects of city life. With careful consideration for protecting green and blue spaces, and some awareness of how to reduce light and noise pollution in the night ― to protect the city’s nocturnal residents ― we can make the night in the city a more just and safe place and time for non-human species too.

about the writer

Huberth Méndez Hernández

Huberth Méndez Hernández is an architect graduated from the University of Design in Costa Rica. He has developed his professional practice at the intersection of the built environment and the natural environment, participating in the development of strategies, plans, and projects related to territorial planning, climate change, environmental performance of buildings, risk management in human habitats, infrastructure impact assessments, human development, and local government management.

Huberth Mendez Hernandez

For many, moths are portrayed as omens of the night; they became archetypes in mythology and superstition.

Moths Karate

Among the many defense mechanisms that moths possess, the one that stands out most—for us Costa Ricans, at least—is “karate”. Receiving a kick or a punch from a moth, no matter how big our little friend is, would never really harm us. Don’t panic—moths have not been trained in martial arts for self-defense. “Karate” is a beautiful metaphor, and its power comes from a deeper source: vernacular narrative and popular knowledge.

At dusk, a ritual unfolds in most Costa Rican homes: the closing of doors and windows to keep out insects—moths and beetles alike. Looking for shelter or attracted by indoor lights, these creatures often find their way inside, making interaction with them imminent. Moths Karate, as my grandmother Hortensia used to call it, could cause a painful rash or an annoying allergy. The intensity of the effect seemed to change as I grew up. According to Hortensia, the closer you get to them, the stronger the reaction. Touching them was strictly off-limits—yet unavoidable due to curiosity.

Moths belong to the Lepidoptera¹ order. Their wings and bodies are armored with micro-scales that function in thermoregulation, aerodynamics, as well as chemical and physical defense. These alchemists are known to use methoxypyrazines² and pyrrolizidine alkaloids³ (PAs) during both larval and adult phases. For physical defense, they evolved to use aposematic warning⁴ signals and to rely on the pareidolia⁵ effect in humans—a large set of skills designed to deter predators from eating or harming them. By shaking their wings, nocturnal moths release a spore-like, atomized compound from their scales, designed to ward off predators and curious humans alike. Such fluttering also aids in pollination, giving flowers one final push while in flight.

Cultural barriers have long been used to control human behavior—often going against our natural instincts. For many, moths are portrayed as omens of the night; they became archetypes in mythology and superstition. This has been a stronger source of influence than chemicals. Much of their behavior has remained unseen, recorded only by those who dwell in infamous, hidden nightly spaces. This demeanor worked very effectively for moths—having a maleficent and toxic halo has likely secured their survival in urban Costa Rica. Beyond Costa Rica’s worldwide reputation, fear has transformed into respect, and respect has mutated into conservancy.

Hortensia was very effective at teaching respect and love for nature to her progeny. She grew up on a coffee plantation, aware of the balance needed for things to flourish. Coffee landscapes back then were mainly nourished by biodiversity—even with the “animosity” of a mythic creature. Moths helped pollinate the white, reflective blossoms of the coffee plants through the dark hours. Now I wonder: hidden beneath the warning of harm lies a preserving narrative, taught by grandmas—perhaps one designed to keep the land producing coffee 24 hours a day, thanks to the unrecognized labor of moths. Or, as I prefer to think, one guided by colloquial fiction and intergenerational love for all living things.

Footnotes (APA Format):

¹ Lepidoptera is the order of insects that includes moths and butterflies, characterized by scaled wings (National Geographic Society, n.d.).

² Methoxypyrazines are aromatic compounds used by insects as chemical signals or deterrents against predators (Boppré, 1984).

³ Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are toxic compounds sequestered by insects from host plants, often used as a defense mechanism (Hartmann, 1999).

⁴ Aposematic warning refers to bright colors or patterns that signal toxicity or danger to predators (Ruxton et al., 2004).

⁵ Pareidolia effect is the tendency of humans to perceive familiar patterns, such as faces, in unrelated objects or shapes (Liu et al., 2014).

about the writer

Rubens de Andrade

Professor Associado I da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Professor do Curso de História da Arte e Paisagismo da Escola de Belas Artes e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura – PROARQ-FAU-UFRJ. Graduado em Arquitetura Paisagismo pela Escola de Belas Artes/UFRJ.

Rubens de Andrade

À noite, perto do cemitério, não é apenas escura; ela é habitada por uma orquestra de sons que, para mentes permeadas pelo folclore e pela tradição, ecoam os sussurros do além, transformando o habitat noturno em um portal para o mistério e o temor.

A Sinfonia Noturna e os Sussurros Do Medo: O Cemitério de Afuá

Read in English.

Leer en Español.

Localizada na ilha de Marajó, Afuá se ergue como uma cidade ribeirinha que se destaca na Amazônia. Seu ritmo de vida desafia convenções sociais e práticas culturais que caracterizam, em grande medida, as cidades da região, sobretudo devido às características morfológicas, que constituem os espaços urbanos e à tipologia arquitetônica, que desenha a sua paisagem. A água e a floresta são os elementos que definem a vida em Afuá. Rios e igarapés servem como artérias que estabelecem relações essenciais entre as comunidades locais, pois esses cursos d’água além de movimentarem a economia local, garantindo a provisão de sustento do seu povo, fomentam, conexões socioculturais vigorosas diante desse ambiente.

Ao percorrer caminhos relacionados à cosmogonia, aos mitos ancestrais e as referências ligadas ao ambiente amazônico, surgem interações ecossistêmicas na qual é possível se deparar com aspectos instigantes da cultura local que se voltam ao espaço cemiterial e, por sua vez, estão ligados à morte e ao morrer. Nesse sentido as epifanias e tradições amazônicas fomentam visões provocativas sobre a compreensão do viver cotidiano, da finitude da vida e do post mortem. O contexto das alegorias sobre o por vir surgem como pano de fundo para a fabulação de relatos que atravessam mentes e corações a partir do Cemitério de Afuá. O frenesi que evoca o sobrenatural, evidenciado através de presságios e rituais, adquire na paisagem distintas representatividades e suscetíveis visualidades sobre o fim de todas as coisas que se consubstancia no lugar-cemitério. Diante de tal propositura a proposta desta reflexão pretende analisar a simbiose existente entre a finitude da vida humana e a força da natureza, a partir do cemitério da cidade.

O lugar onde a morte habita em Afuá é regido diariamente pela alternância das marés dos rios amazônicos, ou seja, o espaço cemiterial é capturado por longas horas do dia pela água. As águas, elemento onipresente em Afuá, ora tocam as bases das sepulturas, ora recuam, revelando a fragilidade da matéria diante da força da natureza. Desse movimento emerge um ar de simplicidade, uma originalidade que brota da adaptação ao meio, uma beleza melancólica que reside na união entre a criação humana e o domínio natural. Não há a solidez da pedra ou o isolamento da terra firme, mas uma entrega ao fluxo da água, uma aceitação da impermanência como parte do ciclo da vida e da morte.

A noite, em sua essência, transcende a mera ausência de luz; ela é um universo à parte, um palco onde a vida urbana adquire contornos distintos. No caso de Afuá, um lugar cortado por rios caudalosos, cercado por uma monumental floresta e abundante em avifauna, a atmosfera de escuridão e de ruídos, naturalmente inundam todos os espaços e dominam a paisagem noturna. Logo, a densa escuridão e os sons da natureza produzem fantasmagorias em uma população já afeita a superestimar as tradições locais, sejam elas ligadas às histórias de mitos ancestrais ou à epifanias que a tradição amazônica, através dos tempos, construiu. Nesse cenário o cemitério emerge como um espelho da alma da cidade, refletindo não somente a reverência à memória dos ancestrais, como também se tornando um terreno fértil para o florescimento de histórias sobrenaturais.

Diante de um cenário amazônico que potencializa as mais variadas interpretações, o campo santo da cidade adquire camadas distintas quando chega a escuridão. A multiplicidade de sons noturnos, diante das tradições culturais locais, são um convite para experienciar um ambiente cercado de misticismos, medos e tensões. O vento que assobia entre as lápides soma-se ao farfalhar das folhas sob os movimentos da coruja. O chiado de sapos, o morcego em voo e o pio distante de uma ave de rapina também estão presentes. Todas essas sonoridades, provocam a imaginação e se estabelecem como um catalisador para os medos ancestrais que habitam o inconsciente coletivo. Nesse sentido surge aqui um jogo selvagem e sensível entre a natureza e a psique humana. A rica fauna local, com seus hábitos noturnos, associado ao movimento das marés que inunda todo o cemitério, com seu ritmo inabalável, não apenas compõem a melodia da noite amazônica, mas também constitui uma mitologia peculiar que redimensiona a cada doa a relação entre a cultura local e o ambiente que cerca o cemitério.

No silêncio quase palpável da escuridão, cada som indistinto, se torna um convite à fantasia, alimentando a crença no inexplicável. À noite, perto do cemitério, não é apenas escura; ela é habitada por uma orquestra de sons que, para mentes permeadas pelo folclore e pela tradição, ecoam os sussurros do além, transformando o habitat noturno em um portal para o mistério e o temor.

La Sinfonía Nocturna y Los Susurros Del Miedo: El Cementerio De Afuá

Por la noche, cerca del cementerio, no solo es oscura; está habitada por una orquesta de sonidos que, para las mentes permeadas por el folclore y la tradición, ecoan los susurros del más allá, transformando el hábitat nocturno en un portal hacia el misterio y el temor.

Ubicada en la isla de Marajó, Afuá se erige como una ciudad ribereña que destaca en la Amazonía. Su ritmo de vida desafía las convenciones sociales y las prácticas culturales que caracterizan, en gran medida, a las ciudades de la región, principalmente debido a las características morfológicas que conforman los espacios urbanos y a la tipología arquitectónica que dibuja su paisaje. El agua y el bosque son los elementos que definen la vida en Afuá. Los ríos y afluentes sirven como arterias que establecen relaciones esenciales entre las comunidades locales; estos cursos de agua, además de mover la economía local y garantizar el sustento de su gente, fomentan conexiones socioculturales vigorosas en este entorno.

Al recorrer caminos relacionados con la cosmogonía, los mitos ancestrales y las referencias vinculadas al ambiente amazónico, surgen interacciones ecosistémicas en las que es posible encontrarse con aspectos intrigantes de la cultura local que se dirigen hacia el espacio cemiterial y, a su vez, están ligados a la muerte y al morir. En este sentido, las epifanías y tradiciones amazónicas fomentan visiones provocativas sobre la comprensión de la vida cotidiana, la finitud de la vida y el post mortem. El contexto de las alegorías sobre lo que está por venir surge como telón de fondo para la creación de relatos que atraviesan mentes y corazones desde el Cementerio de Afuá.

La noche, en su esencia, trasciende la mera ausencia de luz; es un universo aparte, un escenario donde la vida urbana adquiere contornos distintos. En el caso de Afuá, un lugar atravesado por ríos caudalosos, rodeado por una monumental selva y abundante en avifauna, la atmósfera de oscuridad y ruidos, naturalmente, impregna todos los espacios y domina el paisaje nocturno. Por lo tanto, la densa oscuridad y los sonidos de la naturaleza producen fantasmas en una población ya habituada a sobreestimar las tradiciones locales, ya sea relacionadas con historias de mitos ancestrales o con epifanías que la tradición amazónica ha construido a lo largo del tiempo. En este escenario, el cementerio emerge como un espejo del alma de la ciudad, reflejando no solo la reverencia por la memoria de los ancestros, sino también convirtiéndose en un terreno fértil para el florecimiento de historias sobrenaturales.

Frente a un escenario amazónico que potencia las interpretaciones más variadas, el camposanto de la ciudad adquiere capas distintas cuando llega la oscuridad. La multiplicidad de sonidos nocturnos, en presencia de las tradiciones culturales locales, es una invitación a experimentar un ambiente lleno de misticismos, miedos y tensiones. El viento que susurra entre las lápidas se suma al susurro de las hojas bajo los movimientos de la lechuza. El croar de las ranas, el murciélago en vuelo y el lejano piar de un ave de rapiña también están presentes. Todos estos sonidos provocan la imaginación y se establecen como un catalizador para los miedos ancestrales que habitan en el inconsciente colectivo. En este sentido, surge aquí un juego salvaje y sensible entre la naturaleza y la psique humana. La rica fauna local, con sus hábitos nocturnos, junto con el movimiento de las mareas que inunda todo el cementerio con su ritmo inquebrantable, no solo componen la melodía de la noche amazónica, sino que también constituyen una mitología peculiar que redimensiona cada día la relación entre la cultura local y el entorno que rodea el cementerio.

En el silencio casi palpable de la oscuridad, cada sonido indistinto se convierte en una invitación a la fantasía, alimentando la creencia en lo inexplicado. Por la noche, cerca del cementerio, no solo es oscura; está habitada por una orquesta de sonidos que, para las mentes permeadas por el folclore y la tradición, ecoan los susurros del más allá, transformando el hábitat nocturno en un portal hacia el misterio y el temor.

At night, near the cemetery, it is not just dark; it is inhabited by an orchestra of sounds that, for minds permeated by folklore and tradition, echo the whispers from beyond, transforming the nocturnal habitat into a portal to mystery and fear.

The Nocturnal Symphony and The Whispers of Fear: The Afuá Cemetery

Located on Marajó Island, Afuá stands out as a riverside city in the Amazon region. Its way of life challenges social conventions and cultural practices that largely characterize other cities in the area, mainly due to its morphological features that shape the urban spaces and its architectural typology that defines its landscape. Water and the forest are the elements that shape life in Afuá. Rivers and streams serve as arteries that establish essential relationships among local communities; these watercourses not only drive the local economy and provide sustenance for its people but also foster vibrant sociocultural connections within this environment.

As one explores paths related to cosmogony, ancestral myths, and references connected to the Amazonian environment, ecosystemic interactions emerge, revealing intriguing aspects of local culture linked to the cemetery space and, in turn, to death and dying. In this context, Amazonian epiphanies and traditions promote provocative visions about understanding daily life, mortality, and the afterlife. The allegories about what is to come serve as a backdrop for stories that resonate deeply within the minds and hearts of those connected to the Afuá Cemetery. The frenzy evoking the supernatural, evidenced through omens and rituals, takes on different representations and visualities in the landscape, especially around the cemetery, which embodies the concept of endings and finality. This reflection aims to analyze the symbiosis between human mortality and the force of nature, centered on the city’s cemetery.

Night, in its essence, transcends mere absence of light; it is a universe of its own, a stage where urban life takes on distinct contours. In the case of Afuá, a place cut through by mighty rivers, surrounded by a monumental forest, and abundant in birdlife, the atmosphere of darkness and sounds naturally fill all spaces and dominate the nighttime landscape. Thus, the dense darkness and the sounds of nature produce ghostly images in a population already prone to overestimating local traditions, whether they are linked to stories of ancestral myths or to epiphanies that Amazonian tradition has built over time. In this scenario, the cemetery emerges as a mirror of the city’s soul, reflecting not only reverence for the memory of ancestors but also becoming a fertile ground for the flourishing of supernatural stories.

Faced with an Amazonian landscape that amplifies a variety of interpretations, the city’s cemetery takes on different layers when night falls. The multiplicity of nocturnal sounds, given the local cultural traditions, invites one to experience an environment filled with mysticism, fears, and tensions. The wind whistling among the tombstones adds to the rustling of leaves under the movements of an owl. The croaking of frogs, bats in flight, and the distant cry of a raptor are also present. All these sounds provoke the imagination and serve as catalysts for the ancestral fears that inhabit the collective unconscious. In this way, a wild and sensitive game arises between nature and the human psyche. The rich local fauna, with its nocturnal habits, combined with the movement of the tides that floods the entire cemetery with its unchanging rhythm, not only compose the melody of the Amazonian night but also create a peculiar mythology that redefines the relationship between local culture and the environment surrounding the cemetery each day.

In the almost tangible silence of darkness, each indistinct sound becomes an invitation to fantasy, fueling belief in the inexplicable. At night, near the cemetery, it is not just dark; it is inhabited by an orchestra of sounds that, for minds permeated by folklore and tradition, echo the whispers from beyond, transforming the nocturnal habitat into a portal to mystery and fear.

about the writer

Tanja Straka

Tanja is a guest professor in Urban Ecology at the Freie Universität Berlin, with a PhD from the University of Melbourne. She is passionate about understanding how people and wildlife can thrive together in cities. Bridging ecology and social science, her work explores human-wildlife relationships, the drivers of human behaviour, and the impacts of anthropogenic stressors on urban biodiversity, with a special love for bats. Tanja collaborates closely with NGOs and her career has taken her across Europe, West Africa, India, New Zealand, and Australia.

Tanja Straka

If you have not yet had the chance to experience bats in your city, I want to encourage you: go to a nearby waterbody on a warm summer night.

The dark hours in the city were when my work usually began. I have spent countless evenings and nights standing in urban parks, next to urban waterbodies, or even in parking lots and was waiting for the first signs of movement. There is this special moment after sunset, when the last warmth of the sun fades and the city seems to get quiet. And no matter which city I was in, there was always that moment when I heard the first tiny signal on my bat detector. That moment when I also looked up and could see the first bats fluttering around, passing by, or chasing insects. My working hours have begun.

What is the nature of these dark hours in cities? Although our understanding of nocturnal organisms still lags behind that of their diurnal counterparts (Gaston, 2019), for me, these dark hours are, of course, full of life and diversity. Working with urban bats, I am not only fascinated by understanding which bat species live in the urban environment and why, I also like to think that knowing the bat species of a city tells us more about the nature that the city at night holds. Take Berlin, for example. Of the 25 bat species found in Germany, we have around 17 to 18 bat species here with different traits and needs. This tells us that Berlin offers a wide variety of habitats, not only for the more common urban species such as the noctule (Nyctalus noctula) or serotine bat (Eptesicus serotinus), but also for species such as Daubenton’s (Myotis daubentonii) or the brown-long eared bat (Plecotus auritus), which have more specific requirements, broadly including water, trees, or dark areas. It is similar to Melbourne, where around 20 to 25 bat species are known. Here too, we find typical urban bat species such as Gould’s wattled (Chalinolobus gouldii) or the white-striped free-tailed bat (Austronomus australis), but also the little forest bat (Vespadelus vulturnus), which, as the name suggests, relies on trees also within cities. So, protecting diverse urban habitats also means supporting a wide range of different bat species.

However, not just the presence of nature or diverse urban habitats are important. Anthropogenic drivers impact these habitats, and one particularly significant driver for nocturnal biodiversity in cities is artificial light at night. But as we know, light is not just light. The type of lighting, where it is placed, and when it is used make a difference. We may sometimes see bats foraging around streetlights that attract insects. But in reality, only a few bat species can tolerate artificial light at night. For many bats, but also other nocturnal wildlife, lit areas are barriers. More attention and research are being given to what type of lighting is installed, where and when, whether through testing light spectrums that are less disruptive to both people and wildlife, sensor-based systems, or limiting light to areas where and when it is truly needed. However, while this knowledge is certainly important for biodiversity conservation, expert knowledge has now privileged over the perspective of local communities, who may support or oppose such strategies. This is where we need to think about cities as shared habitats, for both humans and wildlife, also at night.

An interesting example that comes to my mind is the River Severn corridor in Worcester, UK (Ferguson et al. 2023). Here, a collaborative project with different stakeholders transformed a brightly lit riverside path that was once a barrier for lesser horseshoe bats into a “shared space”. People continued to enjoy safe access into the city, and the bats returned, along with, quite possibly, other nocturnal wildlife. I like the idea of seeing bats as “nocturnal pandas”, umbrella species of the night whose protection helps safeguard vital ecosystems and many co-occurring species (Kalinkat et al., 2025). After all, by protecting dark islands and corridors in cities, implementing biodiversity-sensitive lighting, and engaging communities even when our focus begins with ‘just’ bats, we certainly also create opportunities for many other nocturnal species in urban areas.

If you have not yet had the chance to experience bats in your city, I want to encourage you: go to a nearby waterbody on a warm summer night. Wait as the last warmth of the sun fades. Even without a bat detector, you might see the first bats fluttering around the vegetation at the water’s edge or above the surface. And perhaps you will also feel that the nature of the dark hours in cities is not an absence of life, but just a different expression of it.

References

Ferguson, J., Fox, H., Smith, N., Brookes, B., Vongpraseuth, M.,Levine, C., Morton, S., Miles, J., Harrison, P., Harding, G., Bolt, E., & Howard, A. (2023). ‘Bats and Artificial Lighting at Night’ Guidance Note GN 08 23: https://www.theilp.org.uk/documents/guidance-note-8-bats-and-artificial-lighting/.

Gaston, K. J. (2019). Nighttime ecology: the “nocturnal problem” revisited. The American Naturalist, 193(4), 481-502.

Kalinkat, G., Jechow, A., Schroer, S., & Hölker, F. (2025). Nocturnal pandas: conservation umbrellas protecting nocturnal biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution.

about the writer

Carolina Rodrigues

Scientific Coordinator at the Landscape Laboratory (Guimarães), an institution dedicated to Environmental Research and Education. Co-chair of the “Green Areas and Biodiversity” working group within the EUROCITIES network since 2019. Was part of the writing team for the winning proposal for Guimarães as the European Green Capital 2026.

Carolina Rodrigues

If we listen closely to the silence of the mountain, we can hear the echoes of this resilient biodiversity, and feel the responsibility to protect it for generations to come.

Night Sentinels of Guimarães

As the city of Guimarães falls silent at night, the Penha Mountain comes to life. This impressive granite massif, standing 613 meters above sea level, is much more than a scenic viewpoint over Portugal’s birthplace — it’s the stage for a surprising nocturnal spectacle, led by mysterious creatures: bats.

Several bat species inhabit this natural refuge. Among the most emblematic are the Lesser horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus hipposideros) and the Escalera’s bat (Myotis escalerai), both listed as Vulnerable in Portugal. The Western barbastelle (Barbastella barbastellus), a forest specialist protected under the EU Habitats Directive, also glides silently above the native tree canopy. These animals find shelter in caves, old mines, tree hollows, and even abandoned buildings on the mountain, such as the cable car structure.

Though discreet, bats are reliable indicators of a habitat’s ecological health. Their constant presence on Penha, confirmed through ultrasonic recordings, signals that a valuable natural balance still exists there. The surrounding forests, including Quercus robur oak woodlands (habitat 9230pt1) and temporary wetland willow groves (habitat 91E0*), provide ideal hunting grounds for species like the Escalera’s bat, which forages for insects on the ground or among fallen leaves. More urban-adapted species, such as the common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) and Kuhl’s pipistrelle (P. kuhlii), often hunt insects attracted to artificial lights.

As part of the Guimarães Biodiversity Action Plan 2030, bats are being monitored throughout the municipality using simple, non-invasive technology. Small devices (AudioMoth®) record the ultrasonic sounds bats emit during flight — sounds inaudible to humans but rich in ecological information. These devices are placed at heights between 2 and 4 meters and record activity during the first hours after sunset, when bats are most active. The recordings are analyzed using specialized software and reviewed by experts, helping to identify species, understand activity patterns, and track how bats use the landscape throughout the year.

However, this delicate balance is under threat. Invasive plant species, poorly managed vegetation, and increasing recreational pressure on the mountain all pose risks to this sensitive ecosystem. Protecting bats means preserving their habitats, their refuges and minimizing the light pollution that interferes with their natural behaviour.

To ensure this protection, community involvement is essential. That’s why the Guimarães Biodiversity Action Plan 2030 promotes training and awareness activities for Green Brigades, schools, and the wider public. These include field outings to observe and monitor various animal groups such as dragonflies (Odonata), butterflies (Lepidoptera), reptiles, and amphibians (herpetofauna), birds, terrestrial mammals, and of course, bats. Guided by experts from the Landscape Laboratory, these experiences blend theory and practice, sparking curiosity and respect for the natural world.

As Sir David Attenborough wisely said: “If children don’t grow up knowing about nature, they won’t understand it. And if they don’t understand it, they won’t protect it”. In the quiet of Penha’s night, bats are more than just skilled hunters. They are guardians of an ancient balance, still alive. And perhaps, if we listen closely to the silence of the mountain, we can hear the echoes of this resilient biodiversity, and feel the responsibility to protect it for generations to come.

Leave a Reply