about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

You are under 30 years old. You wonder about sustainability. You have the mic. What would you say? That is this roundtable. It brings together contributors under 30 years old, both inside and outside the sustainability field—students, designers, healthcare workers, artists, activists, and more. Let’s hear how sustainability feels present—or impossibly distant—and explore why meaningful change still feels hard to grasp.

We talk about young people constantly—in policy documents, in conferences, in news headlines, in endless speeches about “the future”. But when do we actually stop and listen? When do older generations hand over the mic, unclench authority, and hear what is already being said by those under 30—the ones who are not some imagined future, but the present moment in flesh, breath, and urgency?

Sustainability isn’t an abstract word for this generation. It’s the conditions of their lives. Rising seas, collapsing ecosystems, extractive economies, and social injustices are not thought experiments and subjects of research and international treaties—they are the ground beneath their feet. Plus, difficult housing markets and radically transitioning economic landscapes. The world they inherit is maybe not the one they would have chosen. And yet, instead of despair, many bring radical imagination, determination, and vision. They are not waiting to be “leaders tomorrow”. They are already organizing, already building, already disrupting, already demanding change.

This roundtable is not about youth. It is youth. It is a deliberate reversal of roles. The older voices step back. The younger voices step forward. We shouldn’t want them to confirm older people’s assumptions or soften their critique. We are not asking them to recite back tired slogans. (Or are we?) We are asking them to tell us what we have failed to hear, what we have been too afraid to admit, and what must come next.

Maybe I should not dare to summarize what these 27 people say — too much of a trope for an old guy to try and summarize young people — but I can’t help myself: I see four themes:

- Distrust of “Sustainability” as Rhetoric

Many reject sustainability as an empty, commercialized buzzword, often used for greenwashing or to justify suffering. They call instead for transformation, justice, and reciprocity as more honest and urgent frames. - Anger, Anxiety, and Exhaustion as Common Ground

Voices across geographies describe climate grief, fear, and burnout—but also shared anger at inaction by governments and corporations. These emotions are not paralyzing; rather, they become fuel for critique, solidarity, and sometimes humor. - The Power of Local and Everyday Action

Even while critiquing global systems, contributors stress the value of grounded action: protecting local species, redesigning cities, circular fashion, grassroots land justice, and sensory connections to place. The local becomes a way to endure and to reimagine. - Reclaiming Imagination and Vulnerability

Whether through poetry, Indigenous knowledge, architecture, or collective care, contributors call for new ways of imagining futures. Vulnerability and hope are framed not as weakness but as practices of survival, empathy, and resistance.

To read these voices is to be confronted with urgency, but also with possibility. They do not speak in the language of delay, or strategic agreements, or moral victories, compromise, or incremental reform. They speak in an urgent language of survival, justice, and re-invention. They demand that we stop imagining sustainability as a distant horizon and start remaking it in real time.

I, for one, hope they don’t “grow up” and start conforming.

So, how about we listen? Listen as if everything depends on it—because it does.

about the writer

Emmalee Barnett

Emmalee is a writer and editor with a love of nature and stories. She is the editor of TNOC’s magazine and various fiction projects and the Co-director for NBS Comics. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Literature from Missouri State University and currently resides in the tiny town of Spokane, MO.

Emmalee Barnett

I want Earth to heal, but I don’t think it should only be up to us to stitch the wounds.

I don’t believe there is a way to be sustainable in this current era of humanity. They tell us recycling doesn’t work, they always switch back to plastic bags and straws when the new biodegradable ones fall apart, they don’t provide public transport for those of us who don’t want to drive everywhere. God forbid we have actual sidewalks to walk on. It’s always convenience over sustainability. The cheapest option over the right one. My generation has been raised in a world that doesn’t care what tomorrow looks like, as long as we can get what we want right here, right now.

I do not live in a city. I live in the rural Midwest, born and raised in the country where the closest building within walking distance is a cattle barn. I’ve had to drive everywhere because everything (groceries, the bank, the doctors) is, at minimum, thirty minutes away. Sure, I grow my own food, raise my own livestock, grow native wildflower patches, buy local whenever we can, I pick up litter on the side of the road and in creeks whenever I can, I thrift our clothes and have an existential crisis every time I have to throw an article of clothing away because it’s too ratty to be a rag and not worth keeping. But it’s not going to be enough.

For every step I take toward a better future, there will always be someone else on this planet shoving their way three steps back. Before I joined The Nature of Cities, I never really thought twice about the ways everyday people can help the environment. That was always the government’s job, or whoever else is in charge of those things. Of course, I’d help spread the word, hang the posters saying that our planet is dying, and we should do something about it, but no one ever told me what to do. Now, I see all these communities and programs fighting back against our ancestors’ misdeeds and, honestly, I just get desperately angry.

I’m angry that no one in these government positions thinks about the environment first. I’m angry that the world is all about money. I hate the white concrete cubes they build. I hate the subdivisions they build, ruining fields of green grasses and wildflowers to create red clay wastelands and then, in a couple of years, manicured lawns. I hate seeing roadkill every time I drive into town because someone couldn’t be bothered to think of the animals when they expanded the highway. I hate it. Why did anyone let it get this bad?

Greta Thunberg spoke so eloquently at the U.N. Climate Action Summit in 2019,

“You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I’m one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!”

No one wants it to be this way. The “youth” are tired of hearing that we’re the future, we’re the ones who have to bring change, when people in the positions to make actual change right now can just pass it off to the next generation, because that’s easier.

I want Earth to heal, but I don’t think it should only be up to us to stitch the wounds.

about the writer

Nasna Mohamedali

Nasna is a postgraduate in Environmental Engineering with four years of experience in environmental and sustainability planning, permitting, and advisory across diverse city scale projects. Based in Abu Dhabi with AECOM Middle East, she specializes in baseline assessments, sustainability rating systems, ecological mapping using GIS, and environmental protection. Recognized for piloting innovative tools and methodologies, Nasna is committed to advancing sustainable outcomes by combining technical expertise with collaboration, innovation, and continuous learning.

Nasna Mohamedali

I remind myself: every step I take toward making cities more sustainable is a drop in the ocean, but without my drop, the ocean would be less.

When I was a 13-year-old in 2010, I was deeply disappointed by how poorly waste was managed in my hometown in India. There were hardly any waste bins, and segregation was unheard of. Frustrated, I convinced three of my friends to raise this issue with our municipality.

I still remember writing a letter all by myself, something I wish I had saved today, so that the 28-year-old environmental and sustainability planner I am now could look back at the moment it all began. With courage, we went directly to the municipal councillor, presented our concerns, and even showed a video we made of waste dumped across town, explaining how it would pollute our beautiful waterbodies and worsen climate change.

The councillor listened but asked his staff to hand us cleaning equipment, suggesting we clean the town ourselves. At thirteen, it felt disheartening, almost like our effort was being treated as a joke. Still, the four of us tried, and though small, that attempt was my first step into a lifelong journey. That little girl had no idea she would one day dedicate her career to protecting the environment. For her, sustainability, climate change, and biodiversity protection were already real.

Fast forward to today. Sometimes I ask myself if I am doing justice to that dream. I once imagined a life working with NGOs, close to nature, rescuing turtles from the shore, nurturing them, and returning them safely to the sea. Instead, I now work in the corporate world, shaping cities and communities. At times, I wonder: am I protecting the environment, or helping developers destroy it? The question haunted me when I first understood what my career as an environmental and sustainability planner really involved, and, truthfully, sometimes it still does.

But I have learned to reframe it. Development will continue, with or without me. If I left to follow a different path, cities would still rise. Instead, by staying where I am, I can influence how they are built: ensuring clean air, protecting habitats and natural areas, preventing unnecessary tree cutting, designing for walkability and bikeability, improving outdoor thermal comfort, integrating renewable energy, and promoting water efficiency in the desert. This, I realized, is rewriting the way cities are designed and lived in.

It is discouraging when sustainability and climate change are treated as buzzwords for marketing rather than real intention. Yet, I remind myself: every step I take toward making cities more sustainable is a drop in the ocean, but without my drop, the ocean would be less.

That was sustainability, climate change, and biodiversity protection for 13-year-old Nasna. This is sustainability, climate change, and biodiversity protection for 28-year-old Nasna.

about the writer

Emma Andrade

Emma is a third-year undergraduate student at Chaminade University of Honolulu double majoring in Environmental Studies and Environmental Science. She is interested in helping to conserve native species. She currently works with the DLNR at SEPP helping take care of the native Hawaiian tree snails, or Kāhuli.

Emma Andrade

We are the generation inheriting a mess we didn’t take part in creating, but we’re the generation with enough empathy to change the timeline; we are the generation that will turn the tides.

As a 19-year-old working in conservation here in Hawai‘i, I’ve seen firsthand the disconnection that occurs between people now and the land. To me, sustainability isn’t something that should be a “goal” or a “buzzword” in conversations; it should be something that we have already reached. I feel similarly towards climate change; people view it as something that isn’t here yet, something that won’t affect them within their lifetime, but it’s here, now, and it is growing continuously, devastating the more time that goes by without action. I am constantly surrounded by stories from my coworkers and their friends, who speak about what the forests once were. How they have seen the last populations of native species, never knowing that it would be the last time anyone will ever see them.

If I had the mic, I’d be speaking to lawmakers, tourists, and everyday people who think this crisis doesn’t affect them. I’d tell them that their sustainability goals and the delay of climate change can’t be achieved without the implementation of indigenous knowledge into our current systems. I’d say that action without Indigenous voices at the center is incomplete. I’d tell them about my dreams and wishes to see a REAL abundant native Hawaiian forest, where all native flora and fauna can live in harmony.

What needs to be heard is that traditional ecological knowledge is not “old-fashioned”, it’s exactly what we need to guide us through the chaos we’ve created. What we need is more action from both the legislature and the public; we need people working in the field, getting more involved with their communities. The issue is no longer only about creating flashy green tech or carbon offsets to help and solve our problems—it’s about restoring our relationship with the ʻāina. It’s about respect, mutuality, and responsibility.

If I could do things differently, I’d push the local community to grow courage and take more of a lead in conservation efforts, not to just wait on the workers on grant-funded projects to set things up. I’d say to the constant influx of tourists, don’t come to Hawaiʻi for the pretty beaches, and “perfect vacations” if you’re not willing to lend us a hand in protecting what makes them so beautiful. This place isn’t your playground; it’s a living, breathing island that many of us consider our home, and it deserves more than your passive concern. It deserves your action rooted in love, humility, and truth. We are the generation inheriting a mess we didn’t take part in creating, but we’re the generation with enough empathy to change the timeline; we are the generation that will turn the tides.

about the writer

Raychel Ceciro

Raychel is a Floridian eco-anthro-archival performance artist, engaging the past with a preposterous present through urgent tenderness and radical responsibility. Their practice focuses on the handling of delicate information from the primary sources of text, mind, body, and collective memory, specifically those at risk of erasure from climate catastrophe. They have been presented along the east coast in New York and Philadelphia, as well as in many parks, museums, and cultural centers throughout Florida. Their work has been supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Florida Public Archaeology Network. raychelceciro.com

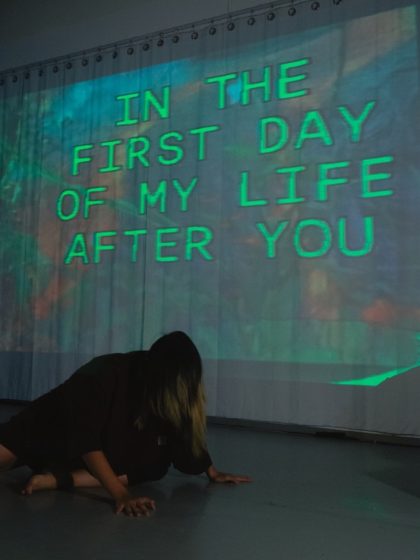

Raychel Ceciro

This isn’t fatalism―it’s an invitation. To destroy what pretends to sustain us. To rip comfort from the root so something unrecognizable, and maybe worth surviving for, can take its place.

I never buy new clothes. I use my wastewater in my plants and garden. I use public transportation to get nearly everywhere with my little OMNY reduced fare card, and nothing about my life is sustainable.

I look around as an NYC transplant from Florida, and it’s just like I’m living in the Capitol from The Hunger Games. I pay rent in the heart of the empire, and nothing I do is sustainable.

Usually, my hot takes around sustainability and the climate crises are, in my opinion, correct, but maybe short-sighted. Cars and the internet should only be allowed for disabled people and environmental workers. Prisons should only be for the rich and their families. Only trans women should be allowed to own guns. Cell phones are fine, but no more Apple products and no more slave labor in the Congo or anywhere. Of course, we should abolish countries and their boarders, BUT if that’s too crazy of an idea (it’s not), only indigenous people should be allowed to run for office. LandBack, duh. Yachts banned, obviously. A liberated and rebuilt Palestine, even more obviously.

The fallout of these changes? None of my business, really.

The first time I had my tarot read in 2022, I pulled the Tower. That year, my dad was hospitalized for 5 weeks, I lost my closest friends, moved away from my home state, started, then dropped out of grad school, and now I am working as an arts administrator with Movement Research while I continue my performing arts practice with the rest of my meager time. My most recent project, WE HAVE TO DO THIS BEFORE WE CAN DO EVERYTHING ELSE, is about the Permian extinction event 250 million years ago: roughly 100,000 years of unbroken volcanic activity that raised global temperatures to 114°F, shredded the ozone layer, and wiped out 90% of all life on Earth. It’s the extinction event scientists study to anticipate what will happen during the current event we are wholeheartedly stewarding to pass. The piece is also about the close queer friendships I lost, and the rage we need to have at the current state of affairs, and how that rage needs to explode and destroy as much as possible, so lichen and moss have the chance to start the growth process over again. If collapse is inevitable, then our work is to clear the ground, so the next era has a fighting chance.

Many of us have heard that entropy is simple, that creation takes the most energy. But the only reason we breathe is because destruction made space for us: ninety percent of species had to burn for the Triassic to wriggle out of the apocalypse; an asteroid had to slam into the planet for mammals to diversify. You are alive because of extinctions before you; you are the fallout of change. This isn’t fatalism―it’s an invitation. To destroy what pretends to sustain us. To rip comfort from the root so something unrecognizable, and maybe worth surviving for, can take its place. Don’t you have to explode?

about the writer

Molly Anderson

Molly is a writer, researcher and creative practitioner from Cape Town. They are interested in how the city is constantly (re)made in rough edges, nests, holes in the road, snags in fences, paths the wind has cleared and places where the grass grows tall.

Molly Anderson

Do we really want sustainability?

No more suffering in the name of Sustainability. We need to transform before we can sustain.

My first reaction to anything mentioning sustainability is to switch off. So much so, in fact, that I missed the other two-thirds of this prompt. I cringe at the word. The concept has been so commercialised, so neatly packaged, that it feels like an empty marker. If someone mentions sustainability, I distrust their motives. I don’t want to talk to anyone about sustainability. I want people with the mics to stop using the word.

But, given there are another two-thirds of a prompt to get through, Kevin and I (Molly) attempt to illustrate why now is not the time for Sustainability in a South African context.

Sustainability: the ability to meet our own needs and maintain our average standard of living without compromising the ability of future generations to do the same. Often, those employing the term pay no attention to whether our “needs” or “standards of living” are appropriate. When people with the mics talk about Sustainability, it is not to ask if or why something should be sustained… just how. While the term refers to the present and the future, it somehow fails to convey the urgency with which we need to act. Sure, we need sustainability, now. But first, we need change, now.

The etymology of the verb “sustain” stems from the Old French sostenir, sustenir, meaning to “hold up, bear; suffer, endure”. These associations provide some insight into our discomfort with the concept: certain people are still required to bear, suffer, and endure in the name of Sustainability (with a big S). Even as young people, we’ve seen promises made and broken.

There are, of course, people and groups doing amazing work to counter climate change, biodiversity loss, and ensure true sustainability, but generally, these people are without the mics and seldom use the term Sustainability. At the recent National Farmworker Platform conference in Cape Town, 17 grassroots organisations gathered to discuss food sovereignty, workers’ rights, and land restitution in the agricultural industry. Despite centring on issues of just social and environmental agricultural practices, the term Sustainability was not used once.

Instead, it is the commercial agricultural industry―a huge contributor to CO2 emissions and biodiversity loss―that uses the term to greenwash extractive social and environmental practices. This is not the status quo that farmworkers and food growers want to sustain. What these organisations want is transformative action and social justice.

A recurring demand at the conference was that of “One woman One hectare”. This, on the surface, is a far humbler goal than that of ‘Sustainability’, but it offers direct steps to address biodiversity loss, social inequality, and contributors to climate change, and has the potential to radically improve lives in an immediately tangible way. Smaller-scale land stewardship allows for more (bio)diversity, while the focus on women and land addresses long-standing social and environmental injustices. The project effectively returns land to those who have been longstanding caretakers of the land and historically dispossessed of it.

No more suffering in the name of Sustainability. We need to transform before we can sustain.

about the writer

Danielle Bongiovanni

Danielle Bongiovanni is a lifelong New Jersey resident who loves local journalism, genre fiction, and her dog. She earned a Bachelor of Science in environmental science at Ramapo College of New Jersey, and is in the process of becoming a Registered Environmental Health Specialist.

Danielle Bongiovanni

Fear is a poor motivator. Guilt is worse. Anger is better, but it burns out. Caring is tiring. No, caring is exhausting. To sustain care, it must be witnessed in marches and the public comment portion of city council meetings. It is the action that comes from the connections with people.

If I could go back in time and talk to the college freshman who declared a major in environmental science and had panic attacks every night thinking about climate change, I would shake her. She wasted so much time feeling alone and hopeless. She spun in circles and did almost nothing of substance. In retrospect, her state of crisis is almost amusing.

When I finished shaking her, I would tell her how first-world countries are and will continue to be comparatively unscathed by climate change. The endless new coverage of deaths, destruction, and evacuations caused by extreme weather events is meager compared to what is happening off-screen. I would give her a moment to find a sick relief in the knowledge that she is exponentially less in danger than billions of people and that, regardless of what she does or what the future holds, she will not see the worst of it.

Then, I would shake her again. I would give her the quick, simple truths that took years to learn. Fear is a poor motivator. Guilt is a worse one. Anger is better, but it burns out quickly. Caring is tiring. No, caring is exhausting.

To sustain care, it must be borrowed from other people. It must be witnessed in marches and the public comment portion of city council meetings and canvassing. In-person is essential. If she misses a day of signing online petitions, sharing posts, and sending pre-written emails to representatives, no one will notice. If she misses an in-person commitment, people will ask if she is alright and help her make the next one.

I would explain how the actions she takes have little to do with her own survival or proving she is a champion for a greener future. Their significance comes from the connections they form with people in her community. If all she looks forward to is the day when the world runs entirely on renewable energy and the only cause of death is old age, she will never be happy. If she looks forward to seeing familiar faces and working together so no one feels alone against insurmountable odds like she once did, she just might.

about the writer

Alba Ortiz Naumann

Alba is passionate about people, nature and outdoor sports. After 10 years working in the environmental movement, across business and non-profit sector, she now researches how social media can foster environmental action through the BIG-5 Project at ICTA-UAB and the Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

Alba Ortiz Naumann

Ultimately, I think of sustainability as a practice of connection: messy, human, and always evolving.

Trying to make sense of these complex issues, especially with so many other injustices going on in the world at the time, is overwhelming. It is no wonder we may feel stuck between apathy and guilt. There is confusion, uncertainty, and the fear of not doing enough or not doing the right thing. But it is worth stepping out of our comfort zone to dare to ask and find answers to these questions.

If I am honest, talking about climate change and sustainability sometimes feels shallow. Not because these aren’t serious issues, far from it, but because they have become buzzwords, overused in so many vague contexts that I feel like they have lost meaning and weight. Sustainability, climate action, net zero. These words are everywhere: on product packaging, in company mission statements, in political speeches. Somewhere along the way, the urgency got replaced with marketing, and the message got watered down into something palatable, clickable, and quick to fix.

The conversation around these issues has always been difficult, and I feel like it is often speaking to those already convinced. It lives in this “eco-bubble”, full of idealism that can alienate others more than it inspires. But what if, instead of focusing on individualized guilt and striving for an eco-perfect lifestyle, i.e., how many flights we take or whether we eat fully plant-based, we shifted the frame entirely? From blaming and finger-pointing to belonging. From “giving up” to “working together to win”. In fact, we are not just consumers making choices. We are citizens with the capacity to act, influence, and shape the spaces and systems we live in. To me, that shift is a transformative act. Sustainability shouldn’t be a product we can purchase or something we can add to our lives when convenient. It needs to be interwoven into how we live, work, and relate to each other. That requires acknowledging not only that we are co-dependent on the people and places that nourish and support us, but also that life holds many contradictions that need to be addressed. Navigating those without falling into the greenwashing trap is a real challenge. For me, the antidote to apathy has always been movement, and what we need now is to sustain our collective movement: action grounded not in fear, but in care. Care for people, places, and the shared visions of our future. Care that moves us out of isolation and into community. We don’t need more facts or inspiration, but the systems in place that support our visions of sustainability.

Ultimately, I think of sustainability as a practice of connection: messy, human, and always evolving. We can both hold the grief of the climate crisis alongside the joy of participating in solutions. We can acknowledge complexity without using it as an excuse for inaction. If we stop searching for the “right” way to be sustainable and instead look for the authentic ways to connect, support, and act, then we might stand a better chance. Not because we were perfect, but because we cared and showed up. Together.

about the writer

Roos Mouthaan

My name is Roos Mouthaan, I’m a 20-year-old Environmental Sciences student with a strong passion for the interplay between society and nature.

Roos Mouthaan

Het is een collectieve taak, en alleen samen kunnen we nieuwe sociale en reproductieve vormen van organisatie bouwen, waarin natuur en samenleving kunnen bloeien.

Wanneer ik met mensen praat over vraagstukken als klimaatverandering en biodiversiteitsverlies, krijg ik vaak dezelfde vraag: waarom zouden we daar energie aan besteden, als er zoveel urgentere en meer tastbare problemen zijn? De prijzen blijven stijgen, jongeren vragen zich af hoe ze ooit een huis zullen kunnen kopen, en zelfs gezinnen waarin fulltime gewerkt wordt, hebben moeite om rond te komen (nog los van de genocide die op dit moment plaatsvindt).

Voor mij kunnen deze uitdagingen niet los van elkaar worden gezien. Economische crises, sociale ongelijkheid, klimaatverandering en biodiversiteitsverlies horen in hetzelfde rijtje thuis. Het zijn symptomen van een systeem dat ons in de steek laat. Overheden, en in nog grotere mate bedrijven, en in bredere zin de samenleving als geheel, blijven jagen op groei, geld en bezit. Deze waarden laten weinig ruimte voor zorg, welzijn en de mogelijkheid om een goed leven te leiden.

Als we echte verandering willen, moeten de problemen bij de wortel worden aangepakt. Een aanpassing in ons dieet of het vermijden van drie vliegreizen per jaar naar een favoriete vakantiebestemming kan ons geweten verlichten en onze ecologische voetafdruk verkleinen, maar het zal niet voldoende zijn. Wat nodig is, is iets fundamentelers: een verschuiving in het systeem dat ons leven vormgeeft.

Dat betekent echter niet dat onze persoonlijke inspanningen er niet toe doen. Ik geloof dat elke kleine actie betekenis draagt. Hoewel “pleisters” de gapende wonden niet zullen sluiten, creëren ze wel rimpelingen van impact. Ze herinneren ons, en onze omgeving, eraan dat een andere manier van leven mogelijk is.

Echter moet ik opnieuw benadrukken dat de verantwoordelijkheid voor een duurzame toekomst niet uitsluitend bij individuen ligt. Het kan overweldigend voelen wanneer we de last van de wereld op onze schouders nemen, terwijl anderen wegkijken of de vooruitgang traag verloopt. Het is een collectieve taak, en alleen samen kunnen we nieuwe sociale en reproductieve vormen van organisatie bouwen, waarin natuur en samenleving kunnen bloeien.

* * *

It is a collective task, and only together can we build new social and reproductive ways or organization where nature and society are able to flourish.

When I talk with people about issues like climate change and biodiversity loss, they often raise the same question: why spend energy on these when there are more urgent, tangible problems? Prices keep rising, young people wonder how they will ever afford a house, and even families working full-time jobs struggle to provide for themselves (not even to touch upon the genocide currently ongoing).

For me, these challenges cannot be seen separately. Economic crises, social inequality, climate change, and biodiversity loss all belong in the same row. They are symptoms of a system that is failing us. Governments, and even more so businesses, and by extension society at large, keep chasing growth, money, and possessions. These values give little space to care, well-being, and the opportunity to live a good life.

If we want real change, the issues need to be addressed at their root. A shift in diet or not flying to your favorite holiday destination 3 times a year may ease our conscience and downsize our carbon footprint, but they will not suffice. What’s required is something more fundamental: a shift in the very system that shapes our lives.

However, that doesn’t mean our personal efforts don’t matter. I believe every small action carries weight. Even though “patches” alone won’t close the gaping wounds, they do create ripples of impact. They remind us, and those around us, that another way of living is possible.

Yet, I must emphasize again that moving toward a sustainable future is a responsibility that does not belong to individuals alone. It can feel overwhelming if we tend to shoulder the burden of the world while others look away or while progress moves too slowly. It is a collective task, and only together can we build new social and reproductive ways or organization where nature and society are able to flourish.

about the writer

Igor Menezes Oliveira

Hi, my name is Igor Menezes Oliveira, I’m 17 years old, I live in Contagem, which is located in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. I study at the Federal Institute of Minas Gerais, on the Ribeirão das Neves campus, where I am studying technical education, studying administration.

Igor Menezes Oliveira

Com esse meu conhecimento básico sobre esse conteúdo, já fica bem evidente que precisamos mudar o mais rápido possível, para que possamos transformar a Terra em um local seguro e habitável para todos!

Eu, como um estudante de ensino médio, acredito que sem a sustentabilidade presente nas nossas vidas, não teríamos a mesma condição de saúde que temos atualmente. A sustentabilidade promove uma consciência dos nossos recursos naturais, presentes no planeta, que, ao mesmo tempo, não provoque diversos desmatamentos de florestas, ecossistemas e muito mais.

Temos que ter consciência de viver bem o nosso presente, pensar no nosso futuro e das novas gerações e, por fim, ser justo com todos, para que ninguém seja afetado com as atitudes dos outros. Sem esse pensamento de que temos que cuidar do agora para vivermos o amanhã, como consequência, podem surgir duas crises graves e as principais: as mudanças climáticas e uma grande crise na nossa biodiversidade (que, infelizmente, está acontecendo nos dias atuais).

A sustentabilidade busca meios que evitam a grande emissão de gases poluentes, mas, sem ela, os gases soltos de maneira irregular criam uma espécie de nova ‘camada’ na nossa atmosfera, sendo assim, aumentando a temperatura do planeta. Já com a perda da biodiversidade, temos uma chance alta de perder diversos recursos naturais que poderiam ser usados para a produção de remédios, matéria-prima e muito mais. Ou seja, seremos impossibilitados de produzir curas para doenças ou até mesmo de encontrar recursos que nem tivemos a possibilidade de conhecer.

Vemos bastante casos de classes mais baixas serem completamente afetadas com essas mudanças e com a falta da sustentabilidade, já que possuem uma maior exposição a essas causas, como, por exemplo, deslizamentos, alagamentos que geram uma destruição enorme e, além do mais, a proliferação de bactérias.

Com esse meu conhecimento básico sobre esse conteúdo, já fica bem evidente que precisamos mudar o mais rápido possível, para que possamos transformar a Terra em um local seguro e habitável para todos!

* * *

With my basic knowledge of this content, it is already quite clear that we need to change as quickly as possible, so that we can transform the Earth into a safe and habitable place for everyone!

As a high school student, I believe that without sustainability in our lives, we wouldn’t have the same health conditions we enjoy today. Sustainability promotes an awareness of our planet’s natural resources while also avoiding deforestation of forests, ecosystems, and more.

We must be mindful of living well in the present, thinking about our future and that of future generations, and, ultimately, being fair to everyone, so that no one is affected by the actions of others. Without this mindset that we must care for the present to live for tomorrow, two serious and major crises could emerge: climate change and a major crisis in our biodiversity (which, unfortunately, is currently occurring).

Sustainability seeks ways to avoid the massive emission of polluting gases, but without it, the irregularly released gases create a kind of new “layer” in our atmosphere, thus increasing the planet’s temperature. With the loss of biodiversity, we have a high risk of losing numerous natural resources that could be used to produce medicines, raw materials, and much more. In other words, we will be unable to produce cures for diseases or even find resources we haven’t even had the chance to discover.

We see many cases of lower classes being completely affected by these changes and the lack of sustainability, as they have greater exposure to these causes, such as landslides, floods that generate enormous destruction, and, furthermore, the proliferation of bacteria.

With my basic knowledge of this content, it is already quite clear that we need to change as quickly as possible, so that we can transform the Earth into a safe and habitable place for everyone!

about the writer

Alex Rivera Campo

I am a student of Political Science and Public Management at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and of Philosophy at the Universitat de Barcelona (UB), majoring inInternational Relations and Political Analysis and minoring in Economics, Politics and Law, respectively. I am also contributing to the interdisciplinary research of BIG-5 a project granted with an ERC on the identification of nature values in digital communities and their impact on environmental stewardship.

Alex Rivera Campo

El reconeixement i la reciprocitat han de ser pilars fonamentals, però cal que siguin dirigits per una visió d’emancipació apuntalat a la idea del reeiximent humà.

M’agradaria anomenar al conjunt de conceptes mencionats (sostenibilitat, canvi climàtic, crisis de biodiversitat, etc) com a crisi de la naturalesa. Una naturalesa de la que formem part i de la qual som agents transformadors actius.

No només una crisi de naturalesa, sinó de naturalització. La modernitat ha buscat comprendre les vicissituds d’aquesta, a través de la ciència empírica, l’economia de mercat i els valors liberals. Aquests pilars constitueixen la crisi de la naturalesa i de la seva naturalització, de la seva normativitat, de la seva inamobilitat, o almenys això creiem.

Vivim en una forma de vida normativament i social empobrida pel domini de l’interès econòmic i la normativització de la naturalesa. Per a revertir això cal comprendre el sistema econòmic del capital com a una forma de vida que ens dirigeix a l’alienació de la mateixa vida, on la mercaderia, diners o capital generen formes de no-reconeixement. De no reconèixer allò que produïm, allò que consumim, aquelles persones que ens envolten, no ens reconeixem ni tan sols a nosaltres mateixos.

És necessari comprendre-ho així, per tal de poder fer ús pràctic de les eines que ens permeten comprendre l’alienació experimentada en el dia a dia, i la persistència dels intercanvis desiguals, entre humans i naturalesa i entre humans mateixos. Eines que no només ens permeten comprendre, sinó que ens dona la possibilitat de construir reconeixement i reciprocitat.

El reconeixement i la reciprocitat han de ser pilars fonamentals, però cal que siguin dirigits per una visió d’emancipació apuntalat a la idea del reeiximent humà. Un reeixir en una terra fèrtil i llum clara on broti i s’edifiqui una societat al voltant de relacions socials interdependents de llibertat humana, natural, total.

* * *

Recognition and reciprocity must be fundamental pillars, but they must be led by a vision of emancipation underpinned by the idea of human flourishment. Flourishing.

I would like to call the set of concepts mentioned (sustainability, climate change, biodiversity crises, etc.) a crisis of nature. A nature of which we are part and of which we are active transforming agents.

Not only a crisis of nature, but of naturalization as simplification. Modernity has sought to understand its vicissitudes through empirical science, market economy, and liberal values. These pillars constitute the crisis of nature and its naturalization, of its normativity, of its immovability, or at least that is what we believe.

We live in a normative and social way of life impoverished by the domination of economic interest and the simplification of nature. To reverse this, it is necessary to understand the economic system of capital as a way of life that drives us to the alienation of life itself, where commodity, money, or capital generate forms of non-recognition. We do not recognize what we produce, what we consume, or those people around us; we do not even recognize ourselves.

It is necessary to understand it in this way, in order to be able to make practical use of the tools that allow us to understand the alienation experienced in everyday life, and the persistence of unequal exchanges between humans and nature and between humans themselves. Tools that not only allow us to understand but also give us the possibility of building recognition and reciprocity.

Recognition and reciprocity must be fundamental pillars, but they must be led by a vision of emancipation underpinned by the idea of human flourishment. Flourishing in the fertile ground and clear light of a society built around interdependent social relationships of human, natural, total freedom.

about the writer

Emily Bohobo N’Dombaxe

Emily Bohobo N’Dombaxe Dola is projects, campaigns and research professional active in the climate justice movement since 2018. Holder of a BA in International Development and an MA in Social Anthropology, Emily focuses on issues and solutions surrounding agri-food systems, nature and biodiversity, adaptation and resilience, and livelihoods and just transition.

Emily Bohobo N’Dombaxe

Whether we sustain, challenge, or transform, civil society should see itself as not a cog in the machine, but as representing all those who give the machine a raison d’être in the first place.

Hope. Disappointment. Resolve. Burnout. Hope. An inevitable cycle one experiences when witnessing power struggles play out within the distant, cold halls of international environmental processes. There, language becomes both a weapon and a shield, a way to settle and escape accountability. Meanwhile, if one remembers to look outside the windows of those seemingly soundproof rooms, the latest episodes of flash floods, heatwaves, and typhoons may very well be eroding the life and harmony that those halls were set up to protect. One can be a firm believer that these processes are necessary to impede further erosion and still understand the increasing cynicism and resentment towards global diplomacy and international institutions. This is an issue that extends beyond environmental politics, also visible in forums concerned with trade, development assistance, human rights, and humanitarianism.

In such circumstances, what’s the role civil society is meant to play? Support or put pressure on governments and institutions to deliver? Mobilise concerned or disaffected members of the public? Work with businesses and corporations to improve their operations or hold them accountable? Should we sustain, challenge, or transform? NGOs, academia, associations, and social movements operate in a third space that gives us plenty of flexibility, but also constrains the impact of our work. Whether it is for funding or for policy impact, we often rely on the power players for our actions to feel effective. That’s what makes the mentioned cycle inevitable; there is (just) so much we can do. Could things be different? While I wish so, I think our difficult position is essential to the fight against the climate and ecological crises. So, the question is: how can we build emotional resilience within our work? Simply being mission-driven or having altruistic values is not enough to remain driven and energised.

To me, the answer is going back to what started it all: life. The ground. Whenever international processes leave me feeling hollow, only the vitality and preciousness of nature can make me feel replenished. We must root our resolve not in the strength of our arguments, the quality of our data, or the measurement of our performance, but in the living beings, communities, and sceneries that make our everyday lives worth it. They, and by extension we, are worth protecting, healing, and maintaining. Furthermore, if those halls of power tend to feel desolate at the end of middling negotiations, maybe it is by design to alienate us as non-parties to these processes? Whether we sustain, challenge, or transform, civil society should see itself as not a cog in the machine, but as representing all those who give the machine a raison d’être in the first place. That’s the only source of resilient hope, hope that won’t easily chip away each time the machine does not deliver.

about the writer

Sally Carpenter

Originally from Wilmette, Illinois, Sally recently completed a Master’s in Smart and Sustainable Cities from Trinity College Dublin. She holds a BA in Psychology with a minor in Environmental Studies from Boston College, where she graduated in 2024. Her research has explored sustainability, social psychology, and communal space design, including her dissertation on communal space in Dublin’s Liberties. Professionally, she has worked with Arup in Strategic Advisory Services and as a Community Development GIS Analyst at Boston College.

Sally Carpenter

When social sustainability is placed at the center, climate action becomes not just a fight for survival, but a chance to build cities and communities where everyone can thrive.

My academic career began in psychology. I went into college interested in the study of human behavior, and drawn to the broad opportunities that a degree in psychology would provide. Looking to explore other topics at my liberal arts college, I took a class in my first semester called Planet in Peril: The History and Future of Human Impacts on the Planet. This was my first real introduction to the field of sustainability and climate change. In that class, we took a historical and sociological perspective on sustainability, reexamining the relationship between human beings and nature. It was from these lectures that I first began to contemplate the complex topics of climate action and environmental justice.

Since that first class, I knew on some level that I wanted to pursue sustainability in my career. However, I also remained dedicated to psychology. In my third year, I joined the Social Influence and Social Change (SISC) Lab at Boston College. I learned during this time that my interest in sustainability and my degree in psychology were not in conflict with one another, but complementary. The people I met working in the SISC Lab were dedicated to the idea that concepts and principles of psychology can be used to influence human behavior in a positive way, particularly in regards to sustainability.

Sustainability is rooted in human behavior, and if there is any hope of climate action on a global scale, then it will depend not just on technology and policy, but on our ability to understand and shift this behavior.

After I graduated, I pursued a Master’s in Smart and Sustainable Cities at Trinity College Dublin, which has recently completed. My dissertation focused on the role of communal spaces in fostering social inclusion and cohesion in dense urban areas.

More specifically, I focused on Dublin’s Liberties, a neighborhood historically underserved in terms of green space and now under pressure from redevelopment. I focused on two contrasting case studies: Bridgefoot Street Park, a public park, and Newmarket Yards, a private development. Through interviews and document analysis, I explored how the design and governance of communal spaces in each case influenced residents’ sense of inclusion, belonging, and justice. Ultimately, the dissertation argues that communal space must be treated not only as a design feature or planning requirement, but as a form of social infrastructure—one that plays a key role in shaping how residents experience inclusion, belonging, and justice in the city.

Sustainability, climate change, and the biodiversity crisis cannot be solved through technology and policy alone. They are human problems at their core, and they demand human solutions rooted in equity and inclusion. When social sustainability is placed at the center, climate action becomes not just a fight for survival, but a chance to build cities and communities where everyone can thrive.

about the writer

Xueyuan Liang

I am Xueyuan Liang. I came from China. I got the Bachelor and Master degree of Landscape Architecture in China. Now I am a Joint PhD student between Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain) and Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium). My research interest is on human-nature relationships and social media data. My PhD research focus on how digital relational values in urban nature environments are expressed and shaped on social media platforms.

Xueyuan Liang

Read this in English.

如果我有发言权,我最想对各国的领导人和企业家说:请不要再把环保当成负担了,它其实是未来发展的机会。

一直以来,我对野生动植物的保护都非常感兴趣。但我经常会听到某些濒危生物灭绝的新闻,这让我很难过也很不安。地球,是人与其他生物共同生活的家园。但为了让步于经济发展,人类挤压并侵占野生动植物的生存空间,进而引起地球环境和气候的变化,最终反噬人类自身。

可持续发展的理念能够引导人类合理地利用自然资源。如果我有发言权,我最想对各国的领导人和企业家说:请不要再把环保当成负担了,它其实是未来发展的机会。比如清洁能源、循环利用、生态农业,这些方向不仅能减轻环境压力,也能带来新的工作和市场。真正的长远利益,是把环境保护放在核心位置,而不是只写在报告里。

与此同时,更多长期被忽视的声音需要被听到。土著居民与生态环境密不可分,他们的日常生活与野生动植物的保护息息相关。但在很多保护或回复项目中,这些土著居民的想法往往被边缘化。因此,我呼吁政府决策者在制定保护策略时能够将当地居民的观点、想法和利益。

行动层面可以分成两个层面。一个是从政府和管理者层面,需要制定更严格的制度,把排放、开发和保护都放在明确的政策框架里。另一个是个人和社区层面出发,每个人都能从小事做起,比如减少一次性用品、支持环保产品,或者参与一些保护野生动物和自然环境的活动。

对我来说,保护野生生命和可持续发展并非遥远的口号,而是我们每天的选择。只要我们愿意去倾听、去行动,就有机会找到一种更平衡的生活方式,让人类和自然能够真正共生下去,实现人与自然的和谐关系。

* * *

If I had a voice, what I would most want to say to world leaders and entrepreneurs is this: Please stop viewing environmental protection as a burden.

I have always been deeply interested in wildlife conservation. Yet I frequently hear news about endangered species going extinct, which saddens and unsettles me. Earth is the shared home of humans and other living beings. However, in the name of economic development, humans encroach upon and seize the habitats of wildlife, triggering changes in the Earth’s environment and climate that ultimately backfire on humanity itself.

The concept of sustainable development can guide humanity toward the rational use of natural resources. If I had a voice, what I would most want to say to world leaders and entrepreneurs is this: Please stop viewing environmental protection as a burden. It is actually an opportunity for future development. Areas like clean energy, recycling, and ecological agriculture not only alleviate environmental pressures but also create new jobs and markets. The true long-term benefit lies in placing environmental protection at the core of our actions, not merely writing it into reports.

Simultaneously, voices long overlooked must be amplified. Indigenous peoples are inextricably linked to ecosystems; their daily lives are intertwined with wildlife conservation. Yet in many protection or restoration projects, their perspectives are marginalized. I therefore urge government policymakers to incorporate local communities’ views, ideas, and interests when formulating conservation strategies.

Action can be divided into two levels. One is at the governmental and managerial level, requiring stricter systems to place emissions, development, and conservation within a clear policy framework. The other originates from the individual and community level, where everyone can start with small actions—such as reducing single-use items, supporting eco-friendly products, or participating in activities protecting wildlife and natural environments.

For me, protecting wildlife and pursuing sustainable development are not distant slogans, but daily choices. By listening and taking action, we can discover a more balanced way of life—one where humans and nature truly coexist, achieving harmony between people and the natural world.

about the writer

Caio Menezes Oliveira

I am Caio Menezes Oliveira, a 20-year-old Brazilian Computer Science student at the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV). I am interested in technology, sustainability, and innovation, and I have participated in projects involving data, machine learning, and environmental initiatives, such as developing an app to support the conservation of the Ribeirão do Onça watershed in the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte.

Caio Menezes Oliveira

It is also of great importance that governments listen to those who truly understand these issues, such as environmentalists, researchers, scholars, and traditional communities, including Indigenous peoples.

For me, sustainability, biodiversity, and climate change are sensitive topics that must be discussed. I say “sensitive” because, in today’s world, there are still people who don’t even believe in these issues.

In my daily life, I often notice small actions connected to these topics. For instance, at my college there are electronic waste collection points and the classic colored recycling bins. In the small city where I live, we also have selective waste collection — a practice I haven’t even seen in some larger cities. Beyond these everyday examples, I also took part in creating an app with my school friends to support the conservation of the Ribeirão do Onça watershed, located in the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Despite this, I know that those actions are too small to really resolve our world’s climate problems, even more so when we consider that this is on a small scale. In view of this, for me, the governments of all the world must be more responsible and held accountable for those questions! Just the hands of governments have the power to improve real changes in effective sustainability, reduce gas emissions into the atmosphere, conduct research into less polluting alternatives, and pressure companies to implement sustainable practices. It is also of great importance that governments listen to those who truly understand these issues, such as environmentalists, researchers, scholars, and traditional communities, including Indigenous peoples.

It is important to emphasize that when I mention governments, I especially mean those in the Global North. These countries should take even stronger measures to support sustainable practices—for example, protecting the Amazon rainforest. Although the Amazon belongs to the Global South, it is of extreme importance for the entire planet, and therefore must be preserved by the whole world. The Global North cannot continue to benefit from global resources while leaving the responsibility of protection solely to the Global South.

about the writer

Roy Fox

Entering Final Year in National College of Art & Design, Dublin, completing a B.A. in Product Design. Alumni of NCAD Field, Spring 2025. Interested in ecological design, permaculture, urban commons, and facilitating interaction with more-than-human worlds.

Roy Fox

Ask how an ant helps you.

There is a gap between what people expect for a sustainable future and what that actually means, for the ability to imagine sustainable futures is constricted to what can happen inside growth economies.

Why is a conversation about conservation always coupled with talking points about GDP or progress?

Has our ability to imagine true change receded over time?

Many of these future visions still exhibit the rhythms of the industrial world of the last two centuries.

It may practice marginally more restraint, but never completely departs from 9-5 work cycles, mass commerce, bananas available any time we want.

These things remain unquestioned for so long that a discussion about ecology seems to entail tearing the entire worldview of most of the urban populace.

What continues to be upheld in nearly every sector is the paradigm that nature serves us, not the other way round.

At times, I believe that no one really cares about things beyond our anthropocene chambers.

Many do not share my sense of awe about bugs in soil, snails in water, ecosystems in micro and macro scales.

It’s not about being unaware of things that lead to environmental destruction; it’s a baseline lack of interest in any other forms of life, bordering on hatred.

Just recently, at a friend’s house, several people were shrieking and flailing after seeing a crane fly hovering around, minding its own business, taking turns trying to kill it, ignoring my suggestion they hoosh it out of the room. Their defense simply amounted to the bug creeping them out. If even this one creature that can’t even bite caused this much of a visceral reaction, I don’t want to imagine how they’d perceive a colony of ants, beetles, creatures that have the audacity to just be alive.

Turns out it doesn’t take much to imagine what that reaction would be.

Walk into any hardware store, and you see this attitude echoed in the explosion of weapons available for little cost.

Entire rows full of slug killer, bug spray, pesticides, herbicides, fly traps, swatters, mouse traps―whole industries built around the systemic erasure of life.

I don’t deny that flies in soup is harmful and should be avoided. Every organisation of species entails a certain level of destruction. But when the feeling remains that anything scary ought to be eliminated, it’s an uneasy foundation to build any discussion on biodiversity.

Even when nature is appreciated, it is so often objectified as a special zone that should exist over there, available to withdraw from when it becomes inconvenient. A garden should be landscaped, pruned, sitting neatly on the edges of cities, but never crossing over. Only containing plants that are appealing to us, even when it doesn’t make sense for the soil networks.

Ask how an ant helps you.

When thinking of a new biodiverse world, before considering only our aesthetic needs and sensibilities, shifting this perspective elsewhere, ever momentarily, may result in a world that is actually fair, now and after we’re gone.

about the writer

Lila Glanville

Lila Glanville is a senior at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York, studying Political Science and Psychology. Lila is originally from Newton, MA, a city outside of Boston.

Lila Glanville

Cities centered around humans are inherently more sustainable.

If I had the mic, I would tell everyone to take a deep breath. I am not going to pretend to be a sustainability, climate change, or biodiversity expert. But it is really easy to get lost in the spiral of climate anxiety. While I believe that climate change and the biodiversity crisis are things we need to be aware of and concerned about, at the same time, I think that intense climate anxiety is counterproductive. Obsessing and stressing over each decision or choice―feeling guilt about using a plastic straw or flying somewhere is unhelpful and unrealistic. Sometimes you have to fly or use that plastic bag.

In middle and high school, I was in on climate change. I rallied with my friends to attend marches, and I was involved in climate change clubs. I attended the NH Youth Climate and Energy Town Hall in 2020. However, the narratives of weather crisis after crisis create an alarmist narrative and generally assume that all weather events are caused by climate change. Whipping people up into a frenzy is not helpful. Climate alarmism? Counterproductive. Yes, in the U.S., it is scary to watch the current President roll back research and regulations from the EPA. Yes, we should all be concerned. But take a breath. I am going to play devil’s advocate here―was it really realistic to cut economy-wide net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 35% of 2005 levels by 2035 (Biden White House, 2024)?

My response to these concerns is that we need to prepare. We need to construct cities for a sustainable future. Cities are homes for people. So, they should be created for people, right? Last year, I spent my junior fall abroad in Copenhagen. I took a course on Urban Livability, which opened my eyes to the design of cities. We learned about how Copenhagen centers and prioritizes people and bikes over motor transportation. I am not saying Copenhagen is the perfect city, but it does much better than most American cities at prioritizing people. After coming back to car-centric America, it was a shock. We discussed Jan Gehl, a Danish architect and urban planner, a champion of “human-centered cities”, cities built on a human scale and urban spaces that promote movement and community, rather than car-oriented design.

The reality of cars is that the assumption was that cars = freedom. However, the reality is that more cars mean more traffic, which leads to less freedom, not to mention the pollution that they bring.

My point is that cities centered around humans are inherently more sustainable. Large cities are lost to parking lots, roadways, and highways, taking away space from the people the city is intended for. The biodiversity crisis is driven by habitat loss and degradation of natural spaces as a result of human activities. This should be addressed by gradually designing cities centered around people.

about the writer

Liseth Carolina Ramirez Canon

I am a young Colombian architect guided by curiosity, care, and collaboration. I’ve had the opportunity to lead and co-create in interdisciplinary groups focused on sustainability, landscape, and social transformation. As a volunteer with Fundación Cerros de Bogotá, I found a deeper sense of nature—its rhythms, resilience, and wisdom—which continues to shape my practice.

Liseth Carolina Ramirez Canon

Read this in English.

Si tuviera el micrófono en mis manos, lo usaría para visibilizar las experiencias que ya demuestran que el cambio es posible.

La sostenibilidad la comprendo hoy como un entramado complejo de interdependencias que sostienen la vida en todas sus dimensiones. No puede reducirse a metas fragmentadas ni a una suma de indicadores, porque responde a sistemas dinámicos donde las relaciones entre elementos generan resultados emergentes que trascienden la lógica lineal. Enrique Leff lo ha señalado al afirmar que la crisis ambiental es también una crisis del conocimiento, resultado de haber intentado comprender la realidad de manera reduccionista. Superar esta mirada exige un pensamiento sistémico y transdisciplinario, capaz de articular saberes científicos, comunitarios y culturales.

La sostenibilidad, en ese sentido, no es un único modelo ni una receta universal, sino una construcción situada, que se alimenta de experiencias comunitarias, de prácticas de cuidado y de vínculos que reconectan lo social con lo ambiental. Más que un concepto abstracto, se consolida en la práctica y en los gestos cotidianos que sostienen la vida. Arturo Escobar lo expresa al señalar que lo que está en juego es la posibilidad de construir alternativas al desarrollo desde las realidades locales y la diversidad de formas de habitar.

En diferentes experiencias con fundaciones y colectivos—entre ellos la Fundación Cerros de Bogotá y el colectivo estudiantil CESCA―he participado en procesos que transformaron mi manera de comprender el territorio. En espacios de diálogo como las Cátedras, y en acciones concretas como los voluntariados de Pacas Digestoras, entendí que la sostenibilidad se aprende en el encuentro: en la acción conjunta, en el cuidado compartido y en la construcción con otros actores y saberes. Estas experiencias no solo tienen un impacto ambiental inmediato; también fortalecen la cohesión social, generan aprendizajes colectivos sobre el valor de los territorios y confirman que lo que no se conoce no se cuida. El contacto directo con la naturaleza despierta conciencia y compromiso.

Como arquitecta concibo mi oficio como una herramienta para interpretar y traducir el territorio, y también para tejer relaciones entre disciplinas, escalas y actores sociales. Cada línea que dibujo no es neutra: puede fragmentar o puede sanar, puede excluir o puede fortalecer el tejido comunitario. La arquitectura, para mí, es una práctica de traducción y de vínculos, una manera de acompañar procesos que reconecten a las personas con lo vivo. La responsabilidad de proyectar, en un contexto de crisis climática y de biodiversidad, es orientarse hacia propuestas que contribuyan al cuidado de la vida y a la construcción de comunidad.

Si tuviera el micrófono en mis manos, lo usaría para visibilizar las experiencias que ya demuestran que el cambio es posible. A mi generación la invitaría a no heredar pasivamente, sino a ser coautora de futuros distintos. A quienes toman decisiones, les recordaría que la juventud es conocimiento y acción, y debe estar incluida en los espacios de gobernanza. Y a la sociedad en su conjunto, le reafirmaría que la vida no se negocia: se protege, se cultiva en simbiosis.

Lo que merece ser escuchado hoy son esas experiencias que demuestran que el cambio es posible. El llamado es a reconocerlas, apoyarlas y aprender de ellas. Todavía estamos a tiempo de construir un futuro donde la vida sea el centro de nuestras decisiones, y ya hemos empezado a hacerlo.

* * *

If I had the microphone in my hands, I would use it to highlight the experiences that already demonstrate that change is possible.

I understand sustainability today as a complex web of interdependencies that sustain life in all its dimensions. It cannot be reduced to fragmented goals or a sum of indicators, because it responds to dynamic systems where the relationships between elements generate emergent results that transcend linear logic. Enrique Leff has pointed this out when he affirmed that the environmental crisis is also a crisis of knowledge, the result of attempting to understand reality in a reductionist manner. Overcoming this view requires systemic and transdisciplinary thinking, capable of articulating scientific, community, and cultural knowledge.

Sustainability, in this sense, is not a single model or a universal recipe, but rather a situated construction, nourished by community experiences, caring practices, and connections that reconnect the social with the environmental. More than an abstract concept, it is consolidated in practice and in the everyday gestures that sustain life. Arturo Escobar expresses this when he points out that what is at stake is the possibility of building alternatives to development based on local realities and the diversity of ways of living.

In various experiences with foundations and collectives—among them the Cerros de Bogotá Foundation and the CESCA student collective—I have participated in processes that transformed my understanding of the territory. In spaces for dialogue such as the Chairs, and in concrete actions such as the Digester Bale volunteer programs, I understood that sustainability is learned through encounters: through joint action, shared care, and building on knowledge and knowledge with other actors. These experiences not only have an immediate environmental impact; they also strengthen social cohesion, generate collective learning about the value of territories, and confirm that what is unknown is not cared for. Direct contact with nature awakens awareness and commitment.

As an architect, I conceive my craft as a tool to interpret and translate the territory, and also to weave relationships between disciplines, scales, and social actors. Each line I draw is not neutral: it can fragment or heal, it can exclude or strengthen the community fabric. Architecture, for me, is a practice of translation and connection, a way of accompanying processes that reconnect people with the living. The responsibility of designing, in a context of climate and biodiversity crises, is to orient ourselves toward proposals that contribute to the care of life and community building.

If I had the microphone in my hands, I would use it to highlight the experiences that already demonstrate that change is possible. I would invite my generation not to passively inherit, but to co-author different futures. To decision-makers, I would remind them that youth is knowledge and action, and must be included in governance spaces. And to society as a whole, I would reaffirm that life is not negotiable: it is protected and cultivated in symbiosis.

What deserves to be heard today are those experiences that demonstrate that change is possible. The call is to recognize them, support them, and learn from them. We still have time to build a future where life is at the center of our decisions, and we have already begun to do so.

about the writer

Samuel Thuo

Samuel Thuo, also known as Sanjotz, is an architect and multisensory design thinker from Nairobi, Kenya. Known as “The Senses Architect,” he explores how buildings and cities can engage all human senses to foster health, happiness, and well-being.

Samuel “Sanjotz” Thuo

I want to see a movement where sustainability is more about people than the planet. Where sustainability is sensorial, intimate, and human.

If I Had the Mic: Sensible Sustainability

When I hear the words “sustainability” or “climate change”, the conversation almost always turns to the planet, carbon emissions, energy metrics, melting glaciers, or disappearing species. Of course, these matter. But what about people, us? What about the billions of us who spend 90% of our lives inside buildings and cities?

As an architect, I feel let down by society, planners, and even my own profession. We preach sustainability through certifications, checklists, and energy models, but we rarely ask: Does this place make people feel alive? Does it touch their senses, foster well-being, and create dignity? Does it connect people with nature?

My frustration is that our cities are majorly designed for efficiency, not experience. Glass towers that trap heat. Highways that drown out silence. Interiors that sterilize touch, smell, and even memory. Places that disconnect us from something bigger than us: biodiversity. We cannot talk about climate action while we continue building environments that deplete our humanity.

We hide “green” features where no one can experience them. A roof garden nobody sees. A rainwater system nobody hears. These may reduce impact on the planet, but they don’t shape human connection. Sustainability becomes invisible, abstract, and ultimately irrelevant to the people it is supposed to serve. When we live in “non-sense” environments, where our senses are starved of biodiversity, we normalize disconnection. And disconnected people cannot truly protect the planet.

Yet, I believe sustainability can be visceral. A naturally ventilated classroom that breathes with the climate teaches children resilience. The smell of timber and stone in a library roots us in place. Courtyards filled with birdsong or filtered light nurture both mental health and ecological systems. This is sensible sustainability: design that heals the planet and the people. In sensible, I don’t mean logical, but smelled, heard, and felt.

If I had the mic, I would say this:

To policymakers, stop treating sustainability as a numbers game.

To architects, stop designing sustainability only for the eye; design for all seven senses. For tactile warmth, thermal comfort, acoustic comfort, and olfactory quality.

To citizens, demand places that nourish all your senses for your health and happiness, not just save kilowatts.

What needs to be heard is simple: sustainability is not only about saving the planet for tomorrow, it is about the people. If people don’t feel sustainability in their bodies, in their daily spaces, they will never care enough to act. We must design cities, buildings, and lifestyles that rekindle our sensory connection with nature. I believe that Sensible buildings facilitate dialogue with nature, while ‘nonsense’ buildings shield us away from nature. Yet, We’re nature, and of nature.

I want to see a movement where sustainability is more about people than the planet. Where sustainability is sensorial, intimate, and human. Not just “sustainable” in technical terms, but sustainable in a way that can be felt, smelled, and heard to all our senses.

That is the sustainability I want to live in. And that is why I act.

about the writer

Jenifer Keyci Soares

Jenifer Keyci Soares, 25 years old, born and raised in Ribeirão das Neves, metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. A sixth-year Pedagogy student at Unopar in Ribeirão das Neves, I currently work as a parliamentary advisor. I became an entrepreneur at 16, creating an online thrift store. Today, through networking and professional experience, I work as a model, stylist, tutor, and image consultant.

Jenifer Keyci Soares

Read this in English.

Não dá mais para esperar: lutar pelo meio ambiente é também lutar pela justiça social.

Sou uma mulher preta, de 25 anos, moradora de Ribeirão das Neves. Sou estudante de pedagogia, já fui professora e hoje trabalho como videomaker na assessoria de uma vereadora. Também sou apaixonada por moda e por bazares, que para mim são mais do que uma forma de vestir: são um ato de resistência, de criatividade e de consumo consciente. É a partir desse lugar que quero falar sobre sustentabilidade, mudanças climáticas e a crise da biodiversidade.

A primeira coisa que me vem à mente é que a nossa cidade precisa se posicionar de forma muito mais ativa nessas questões. Vivo em Ribeirão das Neves desde sempre e, sinceramente, não conheço nenhum projeto consistente da prefeitura voltado para o meio ambiente, para a educação ambiental nas escolas, para o cuidado com nossos resíduos ou para a preservação de áreas verdes. Essa ausência de políticas públicas concretas me preocupa, porque mostra o quanto ainda estamos distantes de uma prática cidadã voltada para o futuro.

Se eu tivesse um microfone na mão, falaria diretamente para duas pessoas: para a juventude da periferia e para os gestores públicos. Para a juventude, diria que sustentabilidade não é só uma palavra bonita: é sobre pensar nosso futuro, nossa saúde e nossa sobrevivência. É entender que quando a gente reutiliza, recicla, compartilha, dá nova vida a uma peça de roupa num bazar ou escolhe uma prática de consumo consciente, a gente está construindo resistência contra um sistema que destrói e descarta.

Para os gestores, eu diria que não dá mais para tratar meio ambiente como um tema secundário. O lixo que se acumula nas ruas, a falta de coleta seletiva, os córregos poluídos, a ausência de espaços verdes e de lazer, tudo isso impacta diretamente a vida das pessoas — especialmente as mais pobres, que são as primeiras a sofrer com enchentes, doenças e falta de qualidade de vida. Precisamos de projetos sérios de arborização, educação ambiental, incentivo a cooperativas de reciclagem e políticas que conectem meio ambiente com geração de renda.

O que precisa ser ouvido é que mudanças climáticas e crise da biodiversidade não são problemas distantes ou abstratos. Elas já estão acontecendo aqui, no nosso cotidiano. Elas estão no calor cada vez mais insuportável dentro das casas sem ventilação, no lixo acumulado que atrai doenças, na água que falta em alguns bairros, nas roupas que chegam até nós de forma barata mas às custas de exploração do trabalho e destruição ambiental.

O que eu faria de diferente é começar pelo exemplo, porque acredito que transformação começa de baixo para cima. Já faço isso no meu dia a dia com os bazares, com a valorização da moda circular e com a consciência de que cada escolha importa. Mas também quero usar meu trabalho, minha voz e meu lugar na política para cobrar da cidade uma postura diferente. Ribeirão das Neves precisa se enxergar como parte do mundo e assumir sua responsabilidade ambiental.

Sustentabilidade é sobre vida. E como mulher preta, sei que nossas vidas sempre estiveram na linha de frente da desigualdade. Não dá mais para esperar: lutar pelo meio ambiente é também lutar pela justiça social.

* * *

We can’t wait any longer: fighting for the environment is also fighting for social justice.

I’m a 25-year-old Black woman living in Ribeirão das Neves. I’m a pedagogy student, a former teacher, and now I work as a videographer for a city councilor. I’m also passionate about fashion and bazaars, which for me are more than just a way of dressing: they’re an act of resistance, creativity, and conscious consumption. It’s from this perspective that I want to talk about sustainability, climate change, and the biodiversity crisis.

The first thing that comes to mind is that our city needs to take a much more active stance on these issues. I’ve lived in Ribeirão das Neves my whole life, and honestly, I’m not aware of any consistent city government project focused on the environment, environmental education in schools, waste management, or the preservation of green spaces. This lack of concrete public policies worries me because it shows how far we still are from a forward-looking civic practice.

If I had a microphone in my hand, I would speak directly to two people: the youth of the periphery and the public administrators. To the youth, I would say that sustainability is not just a pretty word: it’s about thinking about our future, our health, and our survival. It’s understanding that when we reuse, recycle, share, or give new life to a piece of clothing at a thrift store, or choose a conscious consumption practice, we are building resistance against a system that destroys and discards.

To policymakers, I would say that the environment can no longer be treated as a secondary issue. The trash that accumulates on the streets, the lack of selective waste collection, polluted streams, the absence of green spaces and leisure facilities—all of this directly impacts people’s lives—especially the poorest, who are the first to suffer from floods, disease, and a lack of quality of life. We need serious tree planting projects, environmental education, incentives for recycling cooperatives, and policies that connect the environment with income generation.

What needs to be heard is that climate change and the biodiversity crisis are not distant or abstract problems. They are already happening here, in our daily lives. They are present in the increasingly unbearable heat inside unventilated homes, in the accumulated garbage that attracts disease, in the water shortage in some neighborhoods, and in the clothes that reach us cheaply but at the cost of labor exploitation and environmental destruction.