Cities that take nature into account, that shape themselves to work with, not against, nature, are the cities that will repair the damage of the past and set society on a path toward peace and justice for all.

Our city is called New York. Our state is called New York. But who or what is York? As most readers of TNOC might know, it refers to the City of York, in northeastern England. But like with most city names, the name itself starts in nature. In Old Brythonic, the name was Eburākon, the “place of yews”, later transmuted to the Celtic Ebraucus, Latin Eboracum, and the English, York. The not-so-new York lies on the River Ouse close to its confluence with the River Foss, where it grew to become an important medieval city with a towering cathedral.

But that’s now why my city is called New York. York’s place in the history of the British Isles conveyed ancient power and a sense of domination such that the word was adapted as a title of English nobility, the Duke of York. The first Duke of York was Edmund of Langley, born in Herefordshire, from whom the House of York descended, during the terrible years of the War of the Roses of the 1400s. The title died with each duke and had to be recreated by act of the king. Our city’s name originates with the fifth Duke of York, James Stuart, whose brother became Charles II, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, in 1660, during the restoration of the monarchy after the English Civil War. James would later become monarch himself, King James II of England, etc., and then be deposed for his intolerant views and insistence on the divine right of kings during the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688.

You may be wondering what any of this has to do with the nature of cities. But hold on. There is more.

In 1664, Charles II gave his brother a “letter patent,” a document, drawn up on vellum with fancy seals and decorations, giving James permission to take and own all the land from the Delaware River to the Connecticut River, plus New England and Maine, in North America. What was the legal basis of this grant? The asserted right of the English monarch, which is to say, a dubious claim at best … even at the time it was made. Can you imagine if, in our time, King Charles III gave his brother, Prince Andrew, Duke of York, all the northeastern states, from Delaware to Maine? We would laugh. They would laugh. It would be arbitrary and capricious. Moreover, it would be ridiculous.

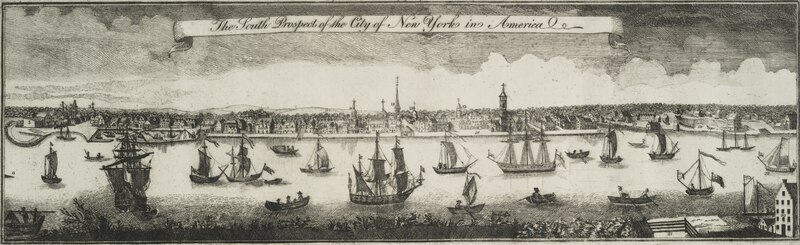

And yet, from this crazy conceit of the 17th century, James derived the Colony of New York. The English set about recognizing all the Dutch land grants and deals made under suspicious and often coercive terms with the Native Americans, who had lived on the land for 8,000–10,000 years already when the Dutch arrived in 1609.

It is from English claims, made under English law, confirming the Dutch land arrangements, that modern New Yorkers derive our property claims. When I apply to the City of New York to add a back bedroom onto my house, the authority of the City to approve my claim derives from the sovereignty of the State of New York, which in turn absorbed its sovereignty from the Colony of New York. When I buy a property, I pay for a title company to confirm the title of the previous owner. The previous owners also presumably had made a title search. If one follows the chain of searches far enough back in time, one would come to some Lenape person making his mark on a paper offered by a Dutchman with a steel pot or a musket, or a barrel of liquor.

These details of New York’s colonization remain important to the nature of the city today, not only because of their inherent injustice and the weakness of the legal claims on which our system of property and sovereignty is built, but because they show how much we live with a culture and ideology derived from those times, even though more than 400 years have passed. From the 17th century, we learned to see the land as natural resources to be extracted, not a community of nature, of which people are only one and not the most important part. From the 17th century, we built into American culture the idea that nature was large, for all purposes, infinite, so no matter how much one person took of those natural resources, there would always be more for others. We assumed that we could pollute the waters and the skies and the land without end because the large and fecund Earth offered continuous new expanses for exploration and exploitation. We bound up ideas of race and gender with uses of nature in ways that explain not only the 17th century but the 21st century as well.

Recovering the nature of New York means more than designing with nature or managing our parklands better. It means more than adapting to a climate caused by polluting the sky or addressing the environmental injustices inherent in the placement of housing and highways. It means changing how we think. It means decolonizing the New York mind.

Central Park in New York City, New York, USA (2012) Photo: Dietmar Rabich

In this vein, it helps to remember that there was a time, and a culture, that had an entirely different ethos about living on this land, in this very place. In the same geographies where we run to the train or make plans or take a meal, the Lenape (Lunapeew) people ran, planned, and ate, in full and unquestioned belief in a clear, obvious, and meaningful connection to nature. They lived in small groups, they practiced matrilineal descent, they recognized distinctions between people and other animals in nature, but didn’t hold themselves above them. Even more striking to the New Yorker, they didn’t need money or higher levels of political organization beyond what a few individuals held in common, and they did just fine.

For thousands of years, 20 times longer than Europeans have lived in this part of the world, the Lunapeew (the “real people” in their language, Munsee) enhanced the biological and functional diversity of the landscape where they lived. They thought of themselves as members of a community of nature. They expressed a profound sense of gratitude and humility to the land and what it gave. One can’t help but wonder, in an alternative version of history, what this place might have been like if their inspired ways of conceiving and living in the world had animated our city rather than the ones brought to us by Henry Hudson, Peter Stuyvesant, and James, Duke of York.

In some sense, I believe that is ultimately what we are seeking in our efforts to bring nature back to the city. Yes, ecosystem services and climate resilience will be provided by restoring nature. Yes, we the people will feel the beneficial effects on our mental health and obtain emotional security from restoring the ecosystems around us. Yes, we will create a habitat that benefits plants and animals. But ultimately, the ambition is to redirect the direction of our civilization. Cities that take nature into account, that shape themselves to work with, not against, nature, are the cities that will repair the damage of the past and set society on a path toward peace and justice for all.

Eric W. Sanderson

New York City

Leave a Reply