I want students to think more intentionally about why they are in college and what they want a future society to look like.

In late April 2025, I took my Introduction to Geography students outside on the campus front lawn. Working in pairs, students were tasked to do the following: (1) to record and describe in detail as many elements of the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere and lithosphere that they could see and feel; (2) to describe what they think are possible interactions between different spheres; and (3) to describe how anthropocentric (human) activities might have changed or are changing each of the four spheres. Each student was provided with a paper worksheet to write down their detailed observations, and everyone was situated together in one area of the lawn looking towards the lakeshore so that they all had the same perspective. Creating the sketch map required them to imagine how the landscape might look from above. My instructions specifically stated that no phones, tablets, or laptops could be used, especially for the sketch map (e.g., no using Google Maps). Both the observations and the sketch map were to be submitted at the end of class.

But two things happened as students began the lab. More than half of the students take out their phones and take a photo of the landscape, then begin to write observations, looking at the photo rather than the real landscape. Several other students attempted to upload the photo of the landscape into ChatGPT so that they could prompt it to make the observations for them. Superficially, this seems typical: Students have always tried to find a way to decrease the amount of effort they put into academic work or avoid it all together. Indeed, in an education system where students are incentivized almost solely to obtain the grades that will get them into university and then hopefully a job, it is inevitable that students look for the easy way out. But this situation ― using GenAI to make observations about a landscape that you are physically sitting in ― has become for me a culmination in the steady decline of students’ curiosity and their abilities to think independently and critically.

The entire activity was designed with the aim of getting students outside, off their phones, and having them observe for themselves. No memory recall was required ― this was not a test or assignment that asked them to regurgitate definitions or even analyse a text. This assignment asked them to use their senses to look at and feel the landscape. So, why then did students not trust their own senses? Were they concerned about recording the “right” observation to obtain the “right” grade? Do they have more confidence in their smartphone and ChatGPT than in their own senses? Or is it that such technology is so much a part of their being that they cannot imagine doing anything without it? Do they have no curiosity about what they might observe? Did they think using a smartphone and GenAI would be faster? Indeed, there were more steps involved in using a smartphone and GenAI.

There are many other questions that emerge from this experience. For me, as a geographer, the most important question to ask is how the need to constantly observe the world (social and natural) through the filter of technology shapes the way that young people understand their place in the world and their relationship to the living and non-living elements? As an educator, I also question how much the current crisis in education is about the lack of confidence in students to make their own observations about the world and the lack of opportunities they have had to develop the skills to generate that confidence? If students do not trust their own experiences and observations about the world they live in, then how can they learn not just to make sense of the world but recognise complex problems and imagine creative ways to address them? I should note here that students do not lack confidence in everything. They are very confident in their observations about social media, and while this is part of the world and important, they have difficulties connecting those observations to other phenomena, which is essential for sense-making.

Sense-making, as I understand and apply it, is the ability to gather, evaluate, and interpret information (from a variety of sources), and then to connect that information to previous knowledge and use it to understand real-world phenomena. It requires curiosity and critical thinking. Sense-making enables people to recognise nuance and complexity in the world. Sense-making depends on a diversity of other skills in combination. In order to gather, evaluate, and interpret information from diverse sources, connect that information to previous knowledge, and apply it to understand real-world phenomena, one must have adequate digital and reading literacy and observational skills. I, along with a multitude of other educators, have witnessed a decline in all these skills, especially over the past five years. Let me provide a few examples to illustrate what is happening in my college classrooms.

Students no longer have basic computer skills, which are key to digital literacy. Indeed, I would classify most of the students as having low digital literacy skills. As many researchers have shown, the idea of younger generations (Gen Z and Alpha, in particular) being digital natives is a myth. While they were born into technology, their knowledge and ability are primarily limited to smartphones and tablets. They struggle to adapt to other tools, devices, and platforms, which is the core of digital literacy. My sixteen-year-old daughter has never taken a dedicated computer science course. Perhaps this is particular to Québec. But for my daughter and the students I teach, there seems to be an assumption at the high school level that students already know how to navigate computers as well as their smartphones.

In my geography class, I introduce geographic information systems (digital mapping and data analysis technology). This technology comprises both online and desktop software, but the data that we use for mapping requires students to use the desktop application. In previous years, students could easily navigate desktop software ― they could find, open, and save files. They knew where the C-drive was. They could figure out the toolbar on their own. I now must teach these basic skills before the students can even attempt to map. This takes time away from introducing digital mapping and spatial data analysis. Another example of limited digital literacy skills is email. When I ask them to email a copy of their mapping file to themselves as a backup to the file on OneDrive (even saving on OneDrive is a struggle for them), students stress over not being able to figure out how to get the file to their phone, where their mail app is. They have no idea how to access their email account from a laptop browser. I see so many students become frustrated with technology, despite the fact that society views them as digital natives. Moreover, students have a lot of difficulty actually reading and understanding maps, never mind creating one.

Another skill that almost all educators see a steady decline in is reading literacy. Reading literacy is the ability to understand, use, evaluate, reflect on, and engage with different types of texts. The ability to write is intertwined with reading literacy. The majority of my students at the first-year college level now struggle to read a 1000-word text (about 1.5-2 pages; this essay is about 2400 words) and then reflect on and compare it with other materials in a class discussion or assignment. By majority, I mean at least 25 students in a class of 40. Part of the problem is that the vocabulary level of most of my students is well below what I experienced 5 years ago and definitely less than 10 years ago. If students do not have the vocabulary, then they have difficulties with reading comprehension, and thus understanding any text.

At the start of each semester, I give students a short survey to get to know them better. I always include questions about what they read on their own ― fiction, non-fiction (biographies, self-help), graphic novels, web-comics, news articles, sports analysis, online magazines, etc. Most students respond that they do not read anything on their own. The decline in the desire to read has been well documented, especially with regard to fiction. But it is not just about reading novels. It is about having the curiosity and confidence to read longer texts about topics that interest them (for example, an interview with a pop singer or a sports analysis). Reading any long-form text exposes young people to a greater number and variety of new words in different contexts. Most importantly, the more one reads, the more confident they are when they encounter unfamiliar vocabulary or sentence structure. Reading long-form also improves focus and attention spans, which are desperately depleted. Vocabulary, reading comprehension, and focus are all required for students to be able to evaluate and engage with information ― critical to both reading and digital literacy, as well as what is now being referred to as AI literacy. If students need to learn how to engage with GenAI properly, then they need to be able to read and evaluate the output. In my social science qualitative research methods class, I have a group assignment where each student brings in the prompts and outputs from a GenAI to analyse and compare. Some of the outputs are longer than 1000 words and contain quite a bit of vocabulary unfamiliar to students, so many students fail to actually understand the output, and they cannot assess and compare it. I see a clear difference between students who read on their own and those who do not. The students who read are far better equipped to engage with GenAI and broader society in creative and interesting ways.

Alongside reading and digital literacy as important elements of sense-making are basic observational skills. These skills involve our ability to perceive, understand, and remember our environment using the five senses (sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste). Observational skills are important for our spatial awareness. What I see in my classes, in particular geography, is that students are no longer able to connect how they move through space (such as getting to the college from home) to reading maps. When I show a map of the island of Montréal, very few students can immediately identify the location of the college, their home, and then Mount Royal (a landmark on the island). Because digital maps always put us at the centre of the “world”, looking at a map without that icon indicating our location is disorientating. Spatially, everything is always in relation to us on the digital map (could we call this spatial narcissism?). This has changed how we see ourselves in the world. When my students pull out their smart phones to take photos of a landscape that they are supposed to be observing in real life and fail to “be present” and to use their own senses, they are missing out on recognising spatial and non-spatial information that would help them to better understand and value the environment and their surroundings, and thus helping them to make sense of their place in relation to the world. This takes us back to my concern about sense-making. Digital, reading, and observational skills, alongside curiosity and creativity, all comprise sensemaking. And this is what I argue students are losing out on right now.

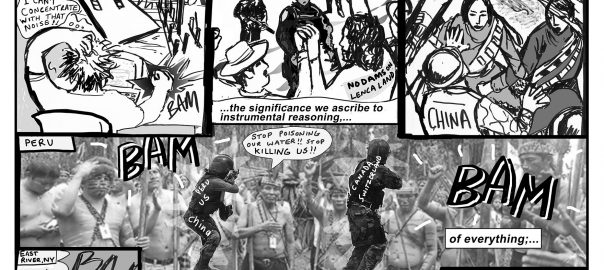

The argument that certain skills are no longer useful today or in the future because we have new technologies (GenAI, etc.) is not helpful, and it puts the future of young people at risk. It limits their capacities as humans to engage intentionally with technology in ways that benefit themselves and society. We are living in a moment of so many complex and serious issues, and if young people are not able to make sense of the world, then addressing problems such as climate change becomes increasingly difficult. There is an opportunity in the current educational crisis (brought on by GenAI) to recognise that all skills are important and that all students should be provided with the possibilities to develop those skills needed to more fully make sense of the world. Technology needs to be adopted more critically and intentionally in education. Educators play a critical role in preparing young people to be engaged and critical citizens, so we need to take this seriously.

Perhaps we need to revisit Donna Haraway’s cyborg manifesto to help us think through how to re-think being human in our techno-social-natural world. Haraway wrote that a cyborg is “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism” (1991, p. 149). With the naturalization of smartphones (and thus social media) and the proliferation of different forms of AI, present-day humans are cyborgs. People are rarely without their smartphones; it is very difficult to carry out everyday tasks without them. They are no longer just tools, but extensions of our bodies and minds.

But Haraway complicates the idea of the cyborg. It is not just the merging of human and machine (and thus nature and culture), but rather a politics and possibility for emancipation. Her concept of the cyborg, as she conceived of it in 1985, was a way to rethink and reconstruct gender and sexuality by challenging or destabilising boundaries. The cyborg is “a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” (p. 149). It is both the concrete materiality of the intertwining of humans and technology (e.g., our smartphones as an extension of our bodies), which reflects and re-configures real-world social-political hierarchies (e.g., who creates, controls, and benefits from technology) and a fictional imagination that serves as reminder that we have the agency to create alternative and intentional ways of being in our social-technological-natural world.

Haraway’s cyborg helps us ask better questions about cyborgs. We can start by asking how we want to be human? What does being human mean? How do we challenge the binary between the material, biophysical (natural) world and our online (cyber) worlds and recognise that both are important in different ways (and not privileging technology just because it exists)? And how do we reconfigure our relations with other humans and the non-human (non-technological) world?

Next semester, I will be starting my classes with Haraway’s cyborg to get students to think about how and when they rely on technology in their everyday lives. I want students to think more intentionally about why they are in college and what they want a future society to look like.

Laura Shillington

Montréal

Leave a Reply