about the writer

Carmen Bouyer

Carmen Bouyer is a French environmental artist and designer based in Paris.

Rivers teach us—about relationship, transformation, non-linearity, flow, renewal, and much more. Their waters carry us into a wider realm—intimate, yet infinitely collective.

Introduction

In an era of ecological urgency, reweaving our relationships with the other-than-human world has become a vital undertaking. The KINSHIP SERIES brings together artists, poets, scientists, biologists, activists, and thinkers from diverse fields to explore how human practices—both personal and collective—can reveal and nurture the intricate web of connections that shape life on Earth. To speak of a tree, a river, or a landscape is to speak of the constellation of beings—human and more-than-human—that create, sustain, and are sustained by it.

This gathering invites a shift in perception: a deepening of our ability to listen, to attune to the many languages, rhythms, and gestures that emerge through interrelation. In this attentiveness, we may find ways to rekindle bonds long neglected, to act with care and reciprocity, and to imagine forms of collaboration that cross the boundaries between species. What new alliances might take root when we recognize ourselves as part of a living, breathing community of Earth? And how might these affinities shape shared futures grounded in mutual care, respect, and the possibility of coexistence? These reflections call us to engage with the wisdom of the Earth itself, to imagine kinship not as metaphor, but as a living practice—rooted, responsive, and regenerative.

As part of this series, the Kinship with Rivers roundtable delves into the deep connections we share with rivers, asking how we can cultivate reciprocal relationships with these living, powerful waters.

Our guests share their personal ways of listening to and conversing with the flowing waters that touch their lives. Through their voices, we are invited to attune ourselves to rivers, brooks, and creeks across the world. With the understanding that we are all made of the same elemental matter—water—that links us across time and geographies.

In this publication, this shared water body takes on many names: Merri Creek in Australia; the Cauca River in Colombia; the Seine, Loire, Rhône, and Bièvre in France; the River Wantsum and River Thames in England; the Khoshk River in Iran; Wadi Shab in Oman; Hudson River, Old Wreck Brook, Gowanus Canal, Tuolumne River, Islais Creek, and Los Angeles River in the United States.

Rivers teach us—about relationship, transformation, non-linearity, flow, renewal, and much more. Their waters carry us into a wider realm—intimate, yet infinitely collective. May these reflections help us recognize how rivers care for us at a deep level and, in return, inspire us to embrace our shared responsibility to care for them. “As bodies of water, how do we care for other waters?” asks ecofeminist philosopher Astrida Neimanis. It’s a question for all of us to approach with our gifts and qualities wherever we are.

As we walk alongside the river, we may feel its fluid motion, its smooth unfolding, and something in us begins to soften. Its presence may invite us into a different way of being—one in which the boundaries begin to dissolve. Our sense of self may blur, until we can no longer say where we end and the river begins.

I tasted selflessness,

I hunger for more of it.

I tell your love-drunk eyes,

I want to see like you,

To shine like you,

To have your unmuddied sight.

That’s what I long for.

A crown, a throne—I don’t need them.

To bow to the ground, to serve Love,

That’s what I long for.

— Jalal al-Din Rumi, excerpt from WATER translated by Haleh Liza Gafori

Read the Kinship with Trees and Forests here.

Elliott Maltby and Gita Nandan

about the writer

Elliott Maltby

Elliott Maltby is a landscape and urban designer. She is a founding partner of thread collective, a multi-disciplinary collaborative design studio that explores the seams between city, art, and landscape. Ms. Maltby believes that art and design can improve the sustainability and vitality of the urban environment; she is particularly interested in how an ecological systems perspective can support both urban and landscape interventions.

about the writer

Gita Nandan

Gita Nandan is an architect, designer, educator, and leader in community resilience planning and design. She is a founder and principal of the award winning design firm thread collective, and chair of the Resilient Red Hook Committee.

Walking With Hidden Rivers

In Paris, in New York, in any city shaped by water, the invitation remains: to notice, to walk, to wonder. To understand that water remembers—and waits for us to do the same.

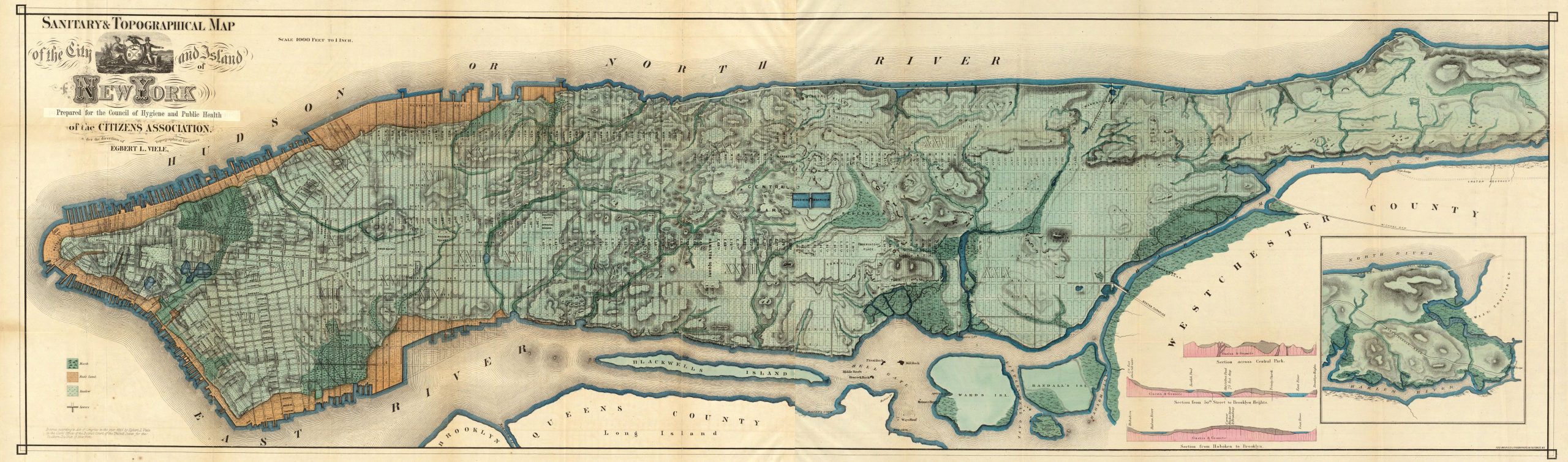

New York City stretches across an archipelago where our many rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The Hudson, Harlem, Bronx, and East Rivers, Gowanus and Newtown Creeks—all move within the vast tidal body of the NYC estuary, one of the most densely populated and deeply altered estuarine systems in the world. This is not just water—it’s brackish memory, a place where salt and fresh, past and future, human and nonhuman intermingle.

For centuries, the estuary sustained life; its oysters filtered the harbor, its wetlands buffered storms, its creeks and marshes held the balance between land and water. And yet, in the drive to build and expand that marks the contemporary human impulse, the estuary was dredged, its wetlands filled and buried, its edges hardened. Today, NYC’s waters are both a site of loss and a wellspring of renewal.

To live here now is to live with that contradiction: to dwell in a place that holds both extraction and abundance, collapse and creativity.

Through research, performance, citizen science, poetic walks, floating gardens, and policy shifts, thread collective is working to create new and diverse cultures of reciprocity. These are practices of collaboration—across species, across scales, across histories – that begin with the willingness to imagine otherwise. To see a polluted canal as a site of potential. To see stormwater as a collaborator. To see the river not as damaged, but as generous and life-sustaining—and to respond in kind.

To understand this relationship, we must reinvigorate our relationship with the Hudson River estuary that cradles NYC. It is not a static backdrop, but a breathing, tidal stage. Its waters move in cycles driven by the moon, shaped by salt and silt, by human labor and buried ecologies.

This short piece unfolds in three acts:

- Act I: The Urban Backstage / Collect Pond Performance

- Act II: The Working Canal / Gowanus Field Stations

- Act III: The Water’s Edge and Beyond / Blue Blocks Gardens

Act I: The Urban Backstage

Beneath the buzz of traffic and scaffolding, New York City hums with an older, quieter rhythm. It is the sound of water, moving, seeping, remembering. Long before the city was a grid of streets and steel, it was a wetland: braided with streams, ponds, and tidal marshes. Though paved over and pushed underground, these waters have not disappeared. They wait in the shadows of infrastructure, tracing old paths in silence. This is the urban backstage, where the traces of the city’s original hydrology still speak.

Collect Pond was a deep, spring-fed lake south of Canal Street, its rich ecosystem a vital source of food and fresh water for the area’s earliest inhabitants. By the early 19th century, it had become a dumping ground for waste and industry, eventually filled in and built over.

Nearby, Old Wreck Brook once linked Collect Pond and Lispenard Meadows, a lush expanse of wetland that absorbed seasonal floods and nurtured wildlife. During particularly high tides, water across the island of Manhattan, connecting the Hudson and East Rivers.

During storms, these forgotten waterways assert themselves. Water pools where it once gathered freely, seeping up through cracks, resisting containment. The city’s vast sewer system, designed to carry water away, overflows, overwhelmed by the very forces it tried to subdue.

To enter into a reciprocal relationship with stormwater, we must first honor these lost ecologies. The Urban Backstage was part of iLAB East River, a collaboration between Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and iLAND [interdisciplinary Laboratory for Art, Nature and Dance] and included the following artists: Julie Kline, Elliott Maltby, Clarinda Mac Low, Jeremy Pickard, Shawn Shafner, and Rachel Stevens. The culmination of six months of creative collaboration, The Urban Backstage is comprised of spaces in the city that, through accident, intention, design, loss, or neglect, allow urban residents to remove their masks, to make mistakes, to expose (or hide) things, thoughts and actions that may not be allowed elsewhere. Water infrastructure is another aspect of the urban backstage; our research explores the individual’s and the city’s relationship to water, waste, and the physical body. Teasing out hidden systems, we trace the systems that connect people to water and use these to connect us to people. This is mirrored in thinking about the tendrils and buried histories of lost waterways, specifically Old Wreck Brook that connected Collect Pond to the East.

Act II: The Working Canal

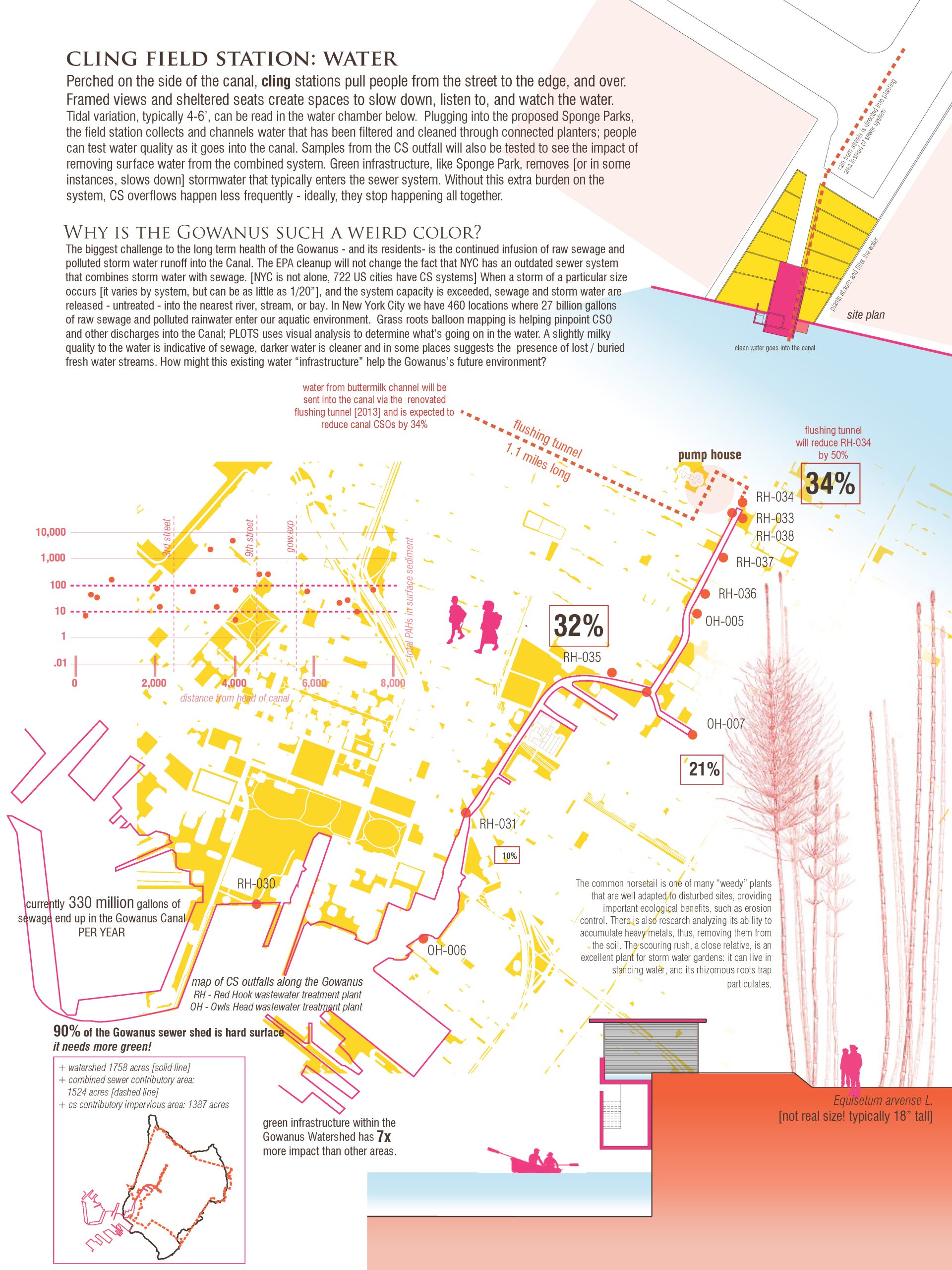

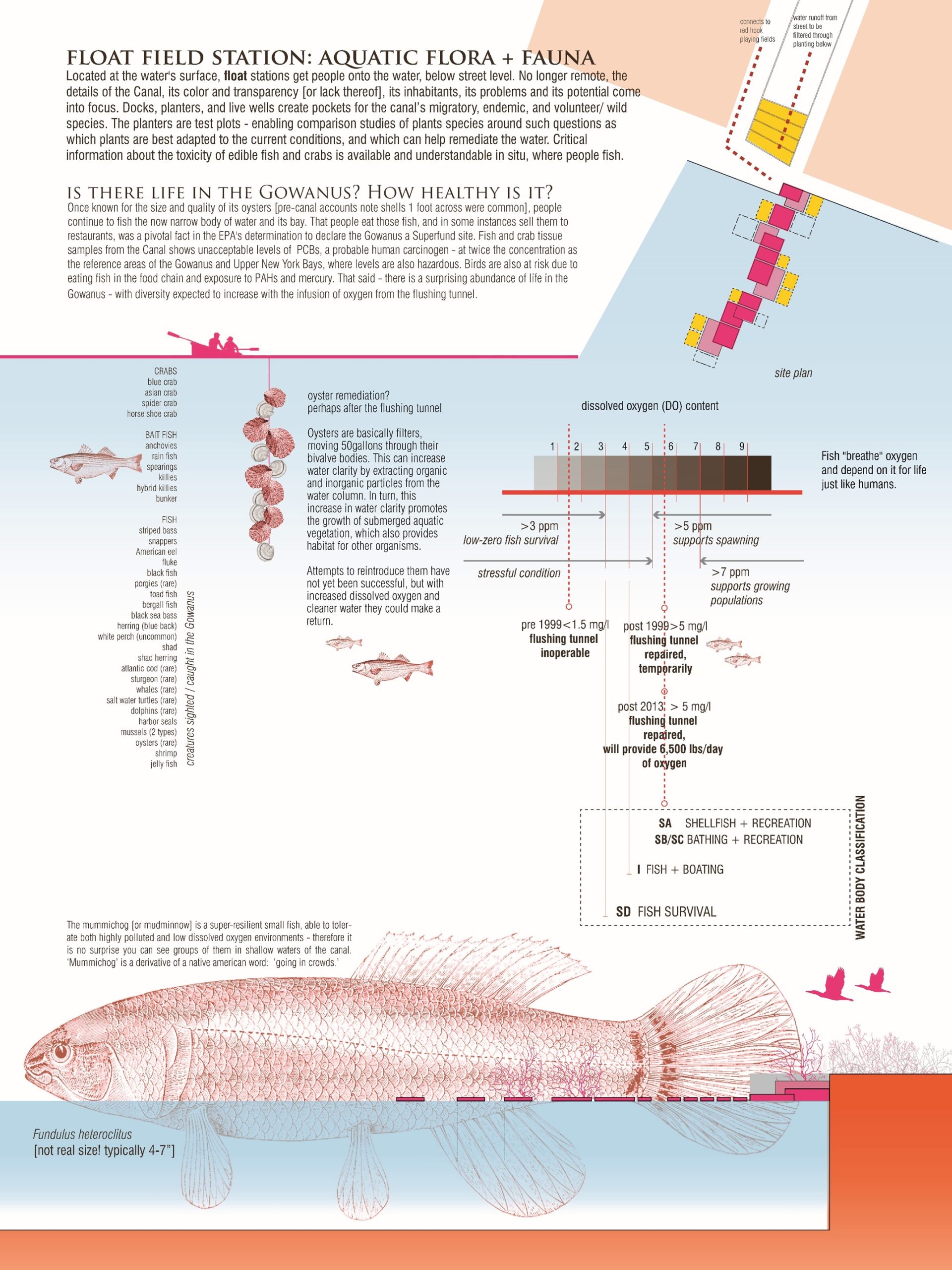

If the urban backstage is where water hides, the Gowanus Canal is where it performs—raw, exposed, and undeniable. The Gowanus Canal is notoriously compelling, a toxic slot cutting into the border of Brooklyn, a public space without much space, full of odd juxtapositions and with a mysterious inscrutability. Hidden at the end of streets and tucked along the side of bridges, patches of spontaneous and some curated ecologies reward the intrepid, the curious, and the local. Dark green waters with a rainbow sheen are home to a surprising number of creatures, their presence and survival seemingly at odds with the complex inherited industrial pollution mixed with contemporary sewage. A constructed waterway, the Gowanus is a sliver of once-extensive wetlands. The canal’s edge is a novel landscape created by years of human use, where endemic striped bass swim under Chinese trees whose seeds were brought to the canal as packing material in the 1800s.

Cut through the body of Brooklyn in the mid-19th century, this narrow, brackish channel was engineered to serve industry: brickworks, tanneries, gas plants. Its waters were not meant to be beautiful—they were meant to work. And they did, absorbing the costs of a city in motion.

It began as Gowanus Creek, a tidal inlet winding through salt marshes and meadows that sustained the Lenape and early settlers alike. But in time, the creek was dredged, straightened, and harnessed for commerce. In its transformation, it became a container for waste, both physical and conceptual. Sludge, heavy metals, and raw sewage accumulated, forming the infamous “black mayonnaise” that still lines the canal’s bottom.

To be in relationship with the Gowanus is to grapple with labor—of water, of people, of restoration. The canal works, still. It receives our runoff, our waste, our attention. The ongoing cleanup is not just an environmental act but a cultural one: an acknowledgment that we have asked too much of water without offering care in return.

Gowanus Field Stations is an exploration of the ecology of the canal through temporary public space installations dispersed along its length. Each field station creates a dedicated space for people to observe and engage with a distinct aspect of the canal: these discrete experiences create a shifting, composite understanding of the area, and recognize the intermingling of human and natural systems.

Act III: The Water’s Edge and Beyond

Where the canal meets the harbor, the city exhales. Gowanus Bay, once a wide tidal basin, now forms the threshold between the industrial heart of Red Hook and the open waters of New York Harbor. Here, the infrastructure of containment gives way to a looser edge—piers, pilings, wetlands in fragments. It’s a place shaped as much by erosion and tide as by planning, where the geometry of the city starts to soften but the hardened rip-rap edge and steel bulkheads hold the imprint of human intervention.

This edge has never been simple. Red Hook itself is a story of marshland filled and refilled, of land borrowed from the sea and constantly at risk of return. Storm surges lap at its boundaries, saltwater rusts its foundations, and rising tides redraw its future. But in this uncertain space, a new kind of relationship is taking form—tentative, imaginative, and alive.

BlueBlocks Gardens are floating, semi-submersible structures planted with salt-tolerant bio-beneficial ecosystems. They now bloom in the harbor’s quiet corners, rafts of native plants rooted in buoyant platforms, absorbing stormwater, providing habitat, and filtering toxins. They are part science, part offering. Unlike bulkheads and sea walls, these floating edges yield rather than resist. They move with the tide. They invite birds, fish, and humans into shared space. They provide a floating footprint for interaction with the water, for marine life to find a home, entice curiosity, and allow for science.

To stand at the water’s edge in Red Hook today is to see possibility layered atop precarity. Behind you, warehouses, trucks, and housing. In front, oyster reefs, floating wetlands, the glint of the Statue of Liberty. Somewhere between, a vision of interspecies coexistence—not perfect, but emerging.

This is not a return to nature, but a making-with—a practice of co-designing futures where water is not pushed away, but welcomed in thoughtfully. Here, at the edge, reciprocity becomes visible: in floating roots, in shared air, in the slow, tidal labor of reweaving kinship between city and sea.

Epilogue: Walking the Invisible River

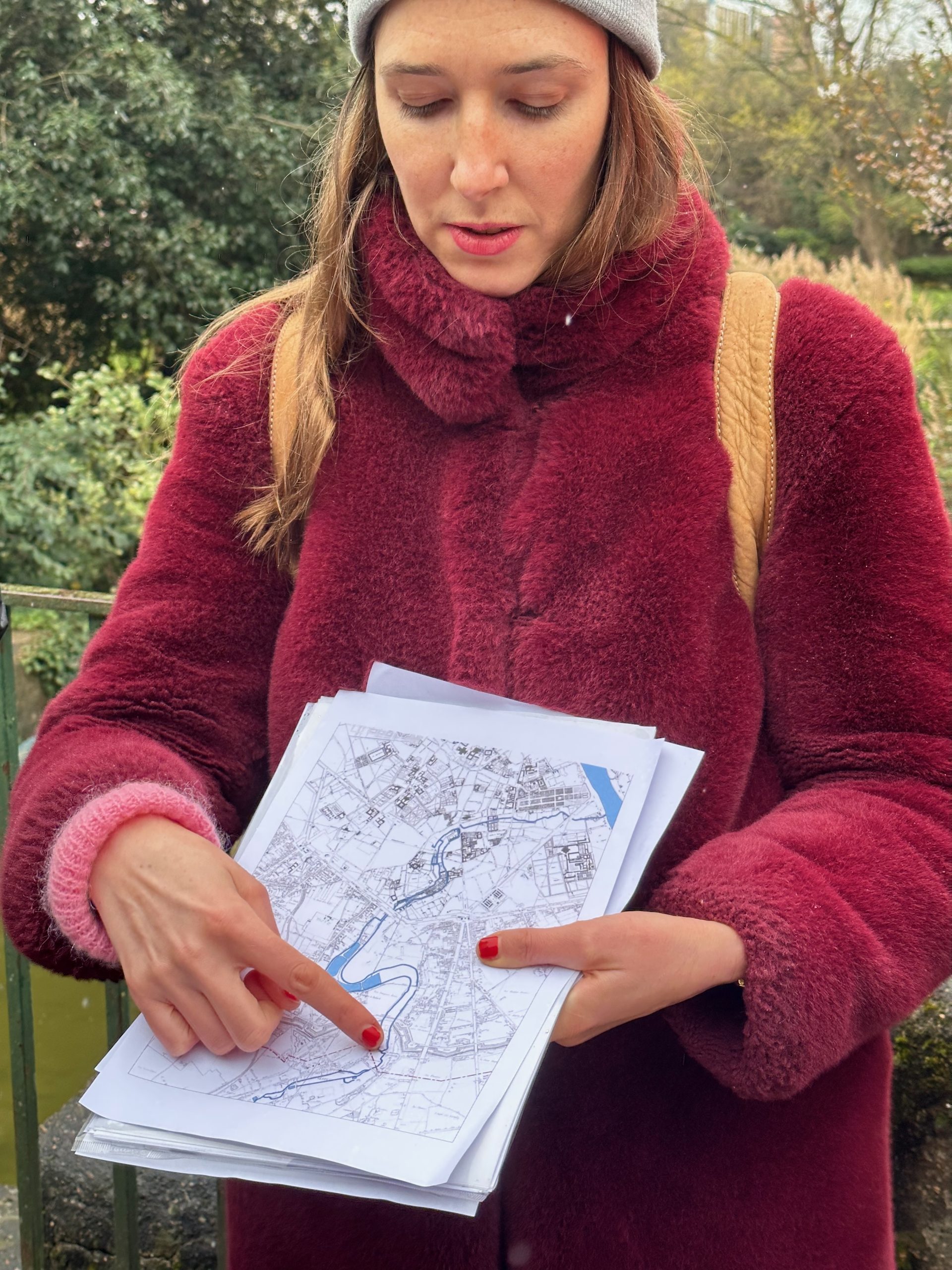

It was raining in Paris the day we walked the path of the Bièvre River, that ancient tributary now mostly buried beneath streets, buildings, and storm drains. Artist Carmen Bouyer led the way, unhurried, attentive, our group of Pratt students following. There were no visible banks, no flowing water. Our map was partial: plaques embedded in sidewalks, subtle shifts in slope, the faint sound of water trapped in infrastructure below.

To walk with a river, even an invisible one, is to enter into a relationship, part imagination, part listening. We weren’t restoring the Bièvre that day. But we were tuning ourselves to it, allowing its absence to shape our awareness.

In Paris, in New York, in any city shaped by water, the invitation remains: to notice, to walk, to wonder. To understand that water remembers—and waits for us to do the same.

Elliott Maltby + Gita Nandan are founding partners of thread collective, along with Mark Mancuso. The studio links innovative and elegant design with multiple ecological and social benefits, including stormwater management, biodiversity, quality public space, and community engagement. As a hybrid architecture and landscape practice, thread collective’s designs explore and are situated within local cultural and environmental ecosystems.

about the writer

Clemencia Echeverri

Clemencia Echeverri is a Columbian artist who explores issues related to violence, memory and the force of nature through video, photography, video installation, sound and interactivity. She currently lives and works in Bogotá.

Clemencia Echeverri

How to Cultivate a Reciprocal Relationship with the Cauca River, Colombia

You need to observe the river: Walk along its banks, observe the health of its waters, the diversity of species it supports, and listen to its sounds. Reconnection begins through presence and observation.

Cultivating a reciprocal relationship with a river means shifting from viewing water merely as a resource to recognizing it as a living entity with which we share mutual responsibilities. In Colombia, this concept has profound meaning, especially with rivers like the Cauca, which has immense ecological, cultural, and spiritual importance. Here’s how you can approach this relationship from a grounded, respectful, and engaged perspective:

- Get to Know the Cauca River Deeply:

The Cauca River (Río Cauca) is Colombia’s second-longest river. It flows for over 1,300 kilometers from the Colombian Massif in the south, through departments like Cauca, Valle del Cauca, and Antioquia, eventually joining the Magdalena River. Understand its ancestral importance: Indigenous groups such as the Misak, Nasa, and Embera have long recognized the river as sacred. It was—and still is—a source of life, transportation, and spiritual significance. You need to observe the river: Walk along its banks, observe the health of its waters, the diversity of species it supports, and listen to its sounds. Reconnection begins through presence and observation.

- It is important to listen to Local and Indigenous Wisdom

- Indigenous communities have lived in reciprocity with the Cauca for centuries. They often see the river as a living relative rather than a resource.

- Participate in or support community rituals, mingas (collective work days), and intercultural dialogues to learn how these communities honor the river.

- Support spaces where traditional ecological knowledge is protected and uplifted.

- Practice Daily River Stewardship

- Avoid contributing to pollution: The Cauca River suffers from heavy contamination due to mining, agriculture, and untreated wastewater from major cities like Cali. Be mindful of your consumption, waste, and how it might ultimately impact the river.

- Engage in restoration efforts: Participate in or organize reforestation projects along the riverbanks, clean-up campaigns, and monitoring of illegal pollution.

- Support sustainable agriculture: Promote practices that avoid chemical runoff into the river basin, such as agroecology and permaculture.

- Advocate for the River’s Rights

- Inspired by the legal recognition of the Atrato River as a legal person in Colombia (2016), some advocates are pushing for similar protections for the Cauca.

- Join or support environmental legal movements that defend the Cauca River from extractivist projects (e.g., hydroelectric dams, mining).

- Pressure local governments to implement existing environmental protection policies and ensure meaningful participation of affected communities.

- Build a Symbolic and Spiritual Bond

- Treat the river as a being: Before entering its waters, ask for permission. After using it, offer thanks. Leave offerings such as flowers or music—not as rituals of consumption, but of connection.

- Create art or writing inspired by the river: This cultivates a sense of reverence and helps others connect emotionally to the river’s story.

- Recognize that reciprocity is not only about taking less—it’s about giving back in forms the river can receive.

Treno, 2007, video projections by Clemencia Echeverr

about the writer

Andreas Weber

Dr. Andreas Weber is a German academic, scholar and writer who holds degrees in Marine Biology and Cultural Studies. Andreas explores new understandings of life-as-meaning or ‘biopoetics’ and ‘biosemiotics’ in science and in the arts, and has authored 15 books.

Andreas Weber

The Seine Is My Mother

I asked the river to allow me to become like water, and what I received was that I became her son.

What follows has been written down during the “Living Waters” seminar in spring 2025, where we explore experimental animism, the communication with rivers. I have been co-teaching this course together with five colleagues from three continents[1] for five years now. About a hundred persons from all over the planet have participated. The seminar relies on two weekly online meetings and regular visits of each participant at their local chosen river. We encourage to approach the river as a person ― introducing oneself, greeting the river, knowing that each gesture is part of a mutual relationship, and spending much time together, as one would in Satsang, guided by a cherished spiritual teacher. The experiences particpants make can be pretty far-reaching, and sometimes even challenging, as they often fall out of the assumption that the world is basically a thing which can only ever be treated as an object[2].

I am in Paris again, or rather right to the west of it, in the suburb of Le Vésinet. The place where I stay is fifty meters away from the Seine embankment. I can see the river from my window. The Airbnb is simple, but the closeness to the river is crucial.

When I came, wheeling my bag with my backpack on top behind me, walking all the way from the RER station, I stopped at the embankment and looked at the glittering reflections on the water. I said my invocation, asked the Seine to allow me to be productive, and pledged to only care for life.

The glitter seemed just that: only life. The river is broad, ships go up and down, those going towards the estuary are hidden behind an island in the middle of the stream, full of trees who are all starting to green these days. The water is grey, green, soft, and shiny. Little waves.

Yesterday, in the night, the Seine to my right, behind some bushes and trees, the water smooth and oily, and barely discernible, I had that moment when She suddenly became a truly living person, a real person, very much like a mother. The whole experience just flipped. The river was my mother.

That’s the state I am still in, although it is weaker now than yesterday. But it comes back in waves, in smooth, low waves like her water. This afternoon I sat in the sun on a bench on the green strip that follows her course, where a path for walkers and cyclists runs along the trees and shrubs that cover the embankment. The river is about five meters below.

I sat there and held that faint feeling of being in the presence of an utmost caring person. Caring for me. Caring for life, for that which needs to be, caring as water is, that always serves the truth as it flows where it needs to flow.

I asked the river to allow me to become like water, and what I received was that I became her son.

I spoke my invocation again. I sat close to the water, in my back two trees covered with pink cherry blossoms and behind them the condo where I am staying. I asked for giving me that experience again, for bathing me in that experience, for never letting me out of it. It is still here, but less strong.

The surface is more green than grey today, very smooth, slow flow, slow waves. I hear a blackbird, a wood dove. There are acacias and plane trees. White wild cherry blossoms. In the oblique light, the glittering, dancing water shows that all wells up just now, everything, the entire reality, just wells up in every instant. Everything is coming into being just now, and I am tended by this being, coming up with it right now.

There is mistletoe in the poplars on the island. A cormorant sits in the barren branches and stretches his wings to let them dry in the late sun. I have just been adopted by the Seine.

Everything is welling up ― the dandelions and the daisies and the pointed blades of the grass, the birdsong and the voices of the passersby in my back. Every movement of every tiny wave is a motion of an immense, soft, pliant body’s flesh. She moves her limbs, her skin, she shivers with life.

“You need to become like water”, the Sufis say. Water, that is loving, because it goes where it is pulled to go, where it is needed. River totally surrenders to being.

But that’s still a thought. The experience that the Seine is a-person-with-me is different. This understanding did not come as intellectual knowledge. It was a stirring within my heart, a breath not taken because of a sudden startle, ―oh, it is so!― and only then it became filled with understanding.

If only we knew what the world truly is. If only this knowledge stayed with us constantly.

It is nearly midnight. I will go to her again in the dark now.

[1] Ezequiel Fugate, Jacqueline Kurio, Freya Mathews, Peter Reason, and Sandra Wooltorton.

[2] For an introduction to this work, it is helpful to look at Peter Reason’s Substack „Learning How Land Speaks“, https://peterreason.substack.com

about the writer

Jessica Taggart Rose

Jessica Taggart Rose is a poet and performer concerned with humanity, nature and how they interact. She lives by the sea in Margate, where she’s part of the Margate Bookie lit fest team and runs Margate Stanza.

Jessica Taggart Rose

What would the river want? To ask this question is a powerful act because it challenges us to step outside of our human-centric perspectives and interests and think in terms of the interests of the more-than-human world.

“Is a river alive?” asks Robert Macfarlane in his latest work of that title. It’s a book he says is written with the rivers that run through its pages. It makes plain our own bodily connection to the bodies of water that flow across our planet:

“Water flows in and through us. Running, we are rivers. Seated, we are pools. Our brains and hearts are three quarters water, our skin is two thirds water. Even our bones are watery.”

Every person likely has at least one river they have connected with. Growing up in landlocked, outback Australia, I spent my summer weekends with my brother in what was mostly a muddy stream, riding airbeds in the current and eating mangoes; thick sticky juices running down our chins into the water.

When I first moved to London, I would walk along the Thames from London Bridge to Rotherhithe, taking leave of the overpopulated metropolis as I sat on a wall watching the open expanse between riverbanks.

Moving to Margate, I have been fascinated by the River Wantsum that once separated the Isle of Thanet from mainland Britain, now silted up to form a flat tract of land demarcating the district boundary.

Restless

There’s something about the continuous movement of a river. The way water makes its way through land and time. How rivers carry us with them. How we carry images and imaginings of rivers in our minds. Somehow, the restlessness of water also calms us. Let it go, it seems to say.

Interconnected

It was a deep connection I sought to make with the River Seine when, studying in Paris during COVID, I found myself walking her banks each day. I was awed at her capacity to house a multitude of species alongside the memories and dreams of human multitudes. I wrote:

Here, beyond the glistening city,

pocket wilderness blossoms:

fungus blooms in creases of steps,

ants, bugs, beetles, venture from nests,

bees get to work, collective.

I match my stride to the river

And we proceed, side by side.

Versatile

Rivers are constantly changing, ever adapting to obstacles, weather, and the activities of species within and around them. They swell and dwindle, race as rapids or meander. In Paris, the Seine regularly floods areas people habitually use, forcing life to work around it.

The river refuses confinement:

scales slopes, floods walks, bursts walls

Enigmatic

While we may think we know a river, its constant shifting means it retains an air of mystery and possibilities for magic. A river is a moving mirror, a mood ring, a perspective shifter. In folklore and stories, rivers can form boundaries or portals between worlds.

Like rain, the river has no colour,

heeds no stereotypes

projects: reflective, subjective, multiple

Reciprocal

Our lives rely on rivers, but can they rely on us? According to the Rivers Trust, in England and Northern Ireland, no single stretch of river is in overall good health. We dump sewage in them, poison and pollute them with chemicals, nutrients, and plastic. So, how do we repair our relationship with rivers?

For me, art and writing have an important role in reactivating our connections to nature, including rivers. When people engage with creative activities using nature as their classroom, a shift occurs.

Professor Miles Richardson’s work on nature connectedness outlines five pathways to nature connection: senses, beauty, emotion, meaning, and compassion. He argues that developing a real sense of connection is more powerful than simply having access to nature and spending time in it. Being both in, and connected to, nature increases our own sense of wellbeing and our propensity to act in nature’s interests.

What would the river want? To ask this question is a powerful act because it challenges us to step outside of our human-centric perspectives and interests and think in terms of the interests of the more-than-human world.

I sometimes wonder whether our polluted rivers miss having people swim in them. I’d like to see cities follow Paris’ lead, taking action to bring our urban rivers back to a point of health where they are safe to swim in. The benefits to all the species that make their homes in and alongside them would be profound.

about the writer

Sareh Moosavi

Dr Sareh Moosavi is a Lecturer in Environmental Planning and Design at the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, The University of Melbourne. Her research and teaching engage with landscape-led and nature-based strategies for fostering climate-responsive urban environments.

Sareh Moosavi

Rivers of liberation, Ecologies of kinship

I cannot help but think that the kinship that we form with rivers is shaped by who we are, where we come from, and our cultural connections to water and land.

The scent of fresh, cool air lingers as the water shimmers in the autumn afternoon light—each ripple whispering stories of the past, present, and future.

As I cycled through the changing landscapes along the Merri Creek (Melbourne, Australia) on a fine Sunday autumn afternoon, thoughts surfaced on how to frame my reflections on kinship with rivers. I kept returning to a feeling of liberation—a quiet, expansive freedom—that rises within me each time I walk or cycle along the winding Merri Creek trail, taking in glimpses of nature amid the bustle of urban life in my second home, Melbourne.

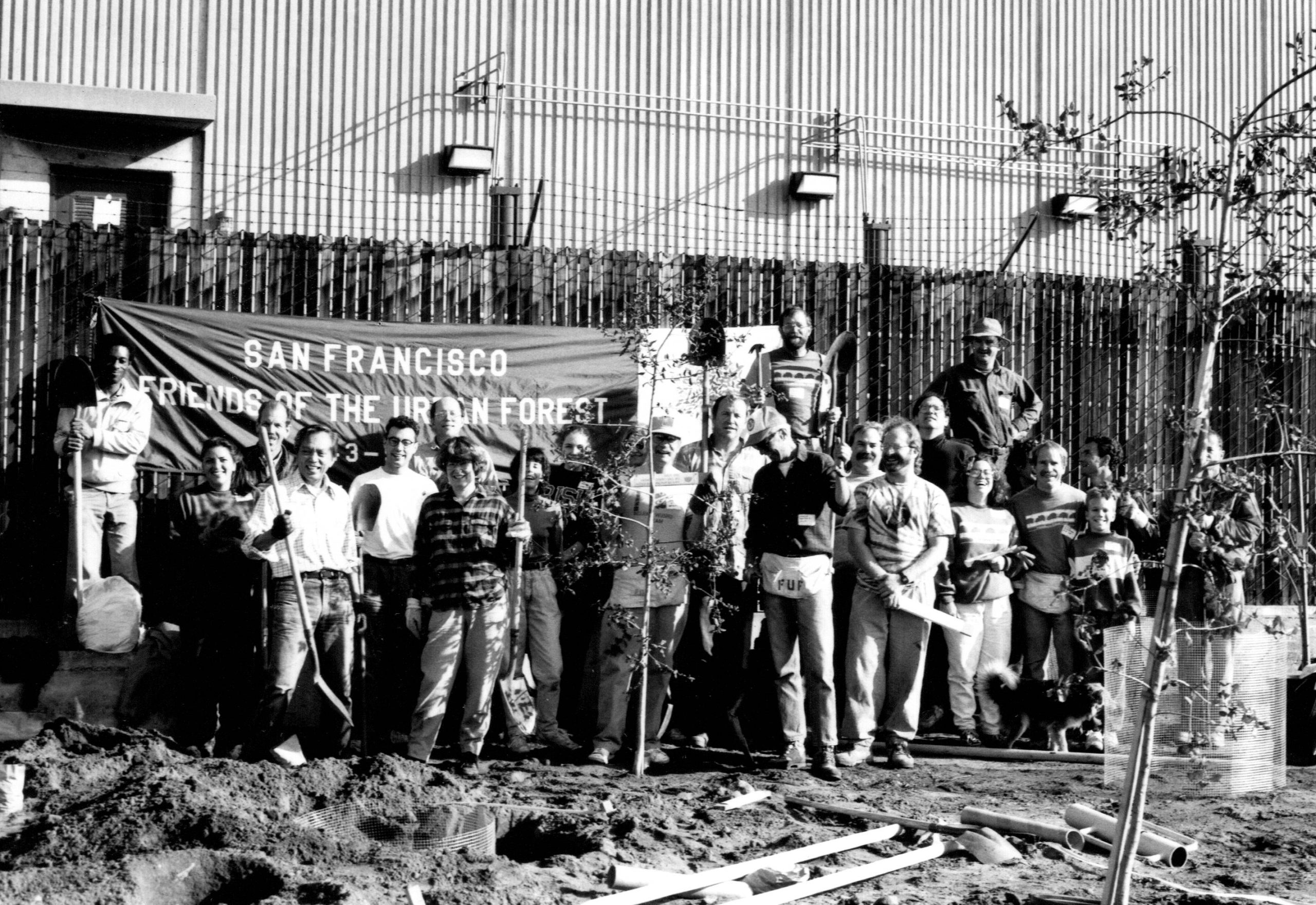

Situated on Wurundjeri Country, Merri Creek was cared for over millennia by its Traditional Custodians. Following colonisation, it endured a period of severe neglect—treated as a dumping ground and overrun with pollution and invasive weeds. Yet, with the help of dedicated stewards, it has been revitalised, and today it’s almost impossible to imagine it otherwise (Figure 1).

I cannot help but think that the kinship that we form with rivers is shaped by who we are, where we come from, and our cultural connections to water and land. This is further influenced by social and political conditions that may have deprived us of a healthy, just, and reciprocal relationship with nature.

To me, urban rivers symbolise both liberation and rebellion—flowing beyond boundaries, crossing borders without permission, carving through concrete, resisting containment, and offering a sense of escape from constructed environments. They are also places of reconnection, a refugium for humans and other-than-humans.

I cannot speak to this roundtable without drawing on my experiences of living in four distinct river cities—Shiraz, Melbourne, Beirut, and Brussels—as well as years of reading, re-imagining, teaching, and researching waterways, including Wadis as public open spaces in aridlands of the Middle East. The line of enquiry into dryland rivers was born out of frustration over what was happening to the Khoshk (dry) River in my hometown, Shiraz: a place where cars have overtaken the lifelines that once nourished its historic gardens (Figure 2). Although I’ve shifted slightly from researching urban rivers to exploring other metabolic flows in cities and the agency of design and planning, I remain deeply intrigued by how our roots and identities, including our ecological interdependencies and political sovereignty shape the ways we perceive rivers as kin, and inspire us to rebuild symbiotic relationships with our landscapes.

As a young woman growing up in Iran, I lived dreaming of the day that I could freely and carelessly cycle along imagined green corridors of the Khoshk River, away from an authoritarian public gaze. These river imaginaries reinforced my perception of rivers as liberating boundaries—symbols of empowerment and freedom.

This is further amplified by their role as spaces of refuge in the face of an increasingly harsh climate reality. I was fortunate to encounter the unique landscapes of Wadis in Oman during my PhD fieldwork in October 2013 (Figure 3). As we walked beneath a scorching sun in search of the renowned turquoise pools of Wadi Shab —about 1.5 hours from Muscat— an oasis appeared, nestled within a narrow canyon of towering, meandering rocks. It offered a refreshing escape amid the extreme heat and arid landscape, evoking feelings of survival, gratitude, and liberation.

Today, these past experiences, memories, imaginaries, and connections continue to shape my quiet conversations with the merry Merri Creek during my daily commutes. Each journey reminds me to slow down and reflect—connecting me to the past while offering a sense of liberation from the present. The story of Merri Creek’s revival also gives me hope for the futures we can imagine for other urban rivers suffering from neglect. Yet, it is a reminder that such transformations require collective care and commitment—they cannot be taken for granted.

References:

- Moosavi, S. (2018). Time, trial and thresholds: unfolding the iterative nature of design in a dryland river rehabilitation. Journal of landscape architecture, 13(1), 22-35. doi:https://10.1080/18626033.2018.1476025

- Moosavi, S., Grose, M. J., & Lake, P. S. (2020). Wadis as dryland river parks: challenges and opportunities in designing with hydro-ecological dynamics. Landscape Research, 45(2), 193-213. doi:10.1080/01426397.2019.1592132

- Moosavi, S., Daniela, P., & and Stephan, A. (2025). Metabolic thinking in planning and designing urban landscapes: practitioners’ perspectives on agency. European Planning Studies, 1-24. doi:10.1080/09654313.2025.2501565

- Jafari, G. (2024). Woman, Water, Freedom. Journal of Architectural Education, 78(1), 104-114. doi:10.1080/10464883.2024.2303926

about the writer

Mary O’Brien

Mary O’Brien is a multi-disciplinary artist—a writer and sculptor who initiates the research and community engagement plans for Studio of Watershed Sculpture the practice she co-founded with artist Daniel McCormick. Using an aesthetic lens, the Studio creates restorative interactions on damaged lands and waters through a scientific trajectory.

Mary O’Brien

Ugly Little Creek

Many waterways have been overused for decades, defiled, then forgotten.

When Yosemite National Park was largely accessible for wilderness camping, we could sit on the banks of the Tuolumne River, high above a 9000-foot altitude, cooling our hike-weary feet in a little whirlpool that formed in front of our campsite. We were close to the source of the river that sprang over massive boulders stacked all the way through the water course, pushing the water up and over in beautiful sprays. We listened to this glorious sound all night long—white noise better than from any app.

Eventually, the River reaches the giant reservoir called Hetch Hetchy, sitting on top of what was once the Little Yosemite Valley, reputed to be even more visually stunning than its larger namesake. A dam funnels water into massive pipes that carry the water downhill via gravity for 160 miles until it nearly reaches the Pacific Ocean. This is San Francisco’s drinking water supply.

San Francisco used to provide its own water, but over a century ago, the city’s many creeks traversing the hills were buried or culverted under buildings, roads, sidewalks, and eventually freeways. The city’s largest creek was one of two that survived. Islais Creek provided 85% of the growing city’s water supply until the early 1900s. The creek ran from a watershed in the center of the city to its eastern border on San Francisco Bay. It dominated the city’s eastern terrain with a series of marshes, traversing streams, and pools nearly two miles wide. But today it is a fragment of its real self. Its valleys and flood plains were developed, and after the 1906 earthquake, the creek’s many channels were filled with demolition debris.

By 1990, Islais Creek had become a 3/4-mile-long concrete channel that begins under a freeway ramp and flows into San Francisco Bay south of the city center. Scores of long banished Gold Rush era slaughterhouses were replaced with a landscape of industrial buildings, warehouses, car dismantlers, and work-yards.

I am reminded of my first introduction to the channel. A tiny triangle of land where I carefully lifted my kayak over strewn slippery chunks of algae-coated asphalt to launch. I didn’t really care about the harsh urban surroundings; I simply wanted to get my boat in the water. This is also where I got my first experience working as an environmental artist and where I met my future partner, and with him, started the art practice we call Watershed Sculpture.

That waterfront spot became the anchor for a restoration project. A largely volunteer effort, we planted nearly 30 native trees. City contractors helped us reactivate large slabs of discarded stone and concrete into seating and picnic tables. An accessible kayak launch and combined viewing ramp was created through state grant funds. Extra lighting was installed at the urging of the community.

On a recent visit, a group of young men jostled on the ramp, casting for fish, but mostly just talking and enjoying beer on a hot July day. I walked to the small sandy beach we had uncovered over three decades ago where our teams helped us remove asphalt debris. The adjacent car dismantlers have left, and a kayaking group stores boats in shipping containers instead.

Islais Creek is still somewhat unattractive. The creek is the same 3/4 mile channelized waterway it was 35 years ago. It has no resemblance to the original source of San Francisco’s original water supply, but we and many others are attracted to the remains of a mighty creek. The human need to be close to the nourishment, expediency, and quenching coolness of waterways runs throughout history. Today, however, it is difficult to find any stream, creek, or river that has been unaltered by humans. This is the story of thousands of water courses across the globe.

Including the Tuolumne River. From late May through September, it refreshes the stunning Tuolumne Meadows which John Muir fought to protect from grazing and other overuse. But today, Yosemite’s infrastructure is getting old, and it is understood that we humans are encroaching too much, even in remote places. The Park Service is pulling campers back from the pristine river we love very much.

Many waterways have been overused for decades, defiled, then forgotten. Some are restored through regulation or citizen action. Like Islais Creek, these streams and rivers will never reach their former glory. However, they can still be sources of life and liveliness in altered environments. Thousands of residents can now get close to the short urban channel, where I paddled my small boat and found love and vocation. Islais Creek is, by definition, a channel, and an ugly channel at that. But it became our ugly little creek, available to neighbors, kayakers, fishers, and others who want to be near accessible water in a city that is surrounded by it, but off limits to most.

about the writer

Marie Saint Bris

Marie Saint Bris is a French poet and ceramic artist living in Paris. Her work sprouts from a profound dialogue with the Earth and its elements. Shaping clay, she explores archaic forms, blending the human with other animal and vegetal realms, honoring influences from Ancient Japan and China. Through her written words, she invites the teaching of rivers and oceans, of her childhood memories, shaping poetic initiatory tales.

Marie Saint Bris

SABLES DE LOIRE

Les arbres vivent des rumeurs passagères

Et le vent courre en farandole.

Sur la crête poudreuse du sable grège,

Des vagues immenses de feu follets

Valsent autour des teintes vertes.

La mouette ivre est remontée jusqu’à nous

Et la mer dégage une odeur de chanvre et de sel.

Elle vibre pourtant très loin d’ici,

Là -bas vers Nantes.

De l’autre côté de cette plage angevine,

Des silhouettes grandioses se dessinent

Sur la presqu’île :

Des vaches maquillées au vert de feuille,

Grimées de noir et de blanc comme de malins échiquiers.

Quelques pêcheurs alanguis près d’une belle génisse orangée,

Sirotent la Loire par gouttelettes, ténébreux accrochés à leur ligne.

D’autres autochtones plus fiévreux traversent un bras de Loire,

La main haut levée afin de protéger leurs chausses,

Quitte à tenter une mission impossible à contre-courant

Et s’embarquer plus loin sur une île aux maisons abandonnées sans toits et sans panache.

English Translation

SABLES DE LOIRE

The trees are alive with fleeting rumours

And the wind runs in a farandole.

On the powdery crest of the grey sand,

Immense waves of will-o’-the-wisps

Float around the green hues.

The drunken seagull has come up to us

And the sea smells of hemp and salt.

Yet it vibrates far from here,

Down there towards Nantes.

On the other side of this Angevin beach,

Grandiose silhouettes can be seen

On the peninsula:

Cows in leaf-green make-up,

Dressed in black and white like clever chess boards.

A few fishermen languish next to a beautiful orange heifer,

Sipping the Loire in droplets, darkly clinging to their line.

Other, more feverish natives cross an arm of the Loire,

Hands raised high to protect their shoes,

Even if it means attempting an impossible mission against the current

And embarking further on an island of abandoned houses with no roofs and no panache.

about the writer

Margaux Balloffet

Margaux Balloffet is a French investigative journalist focused on ecological issues, a hydrofeminist, and a curator. She founded Les Femmes en Avant in 2020, an ecofeminist exhibition series amplifying feminist struggles and ecological urgencies.

Margaux Balloffet

The river is not “out there”. It’s within us. In our blood. In our saliva. In our tears.

We are made of water. And that’s not a metaphor.

I am a woman of water. I am made of tides. I disobey imposed currents of thought. My hydrofeminist thinking isn’t born from a manifesto, but from a wild flow—a way of feeling that what binds us—artists, rivers, bodies, fibers, poems is this liquid matter that slips between fixed forms, that insinuates itself where we wanted to block out, freeze, erase.

I look at the works of Clémence Vazard, Angela Jiménez Duran, Kerid Wengilbert—and I immediately feel that we speak the same language: that of water, which needs no grammar to express what is essential.

Clémence listens to water as one listens to a loved one: patiently, humbly, dropping the filters. In The Word of Water, she doesn’t seek to dominate color, but to co-create with the Rhône River, the salt marshes, the irrigation canals. Water is not a neutral solvent—it is a living organism, a collaborator. Its hues speak of pH, minerals, and even suffering—the wounded water becomes darker, it cries out softly.

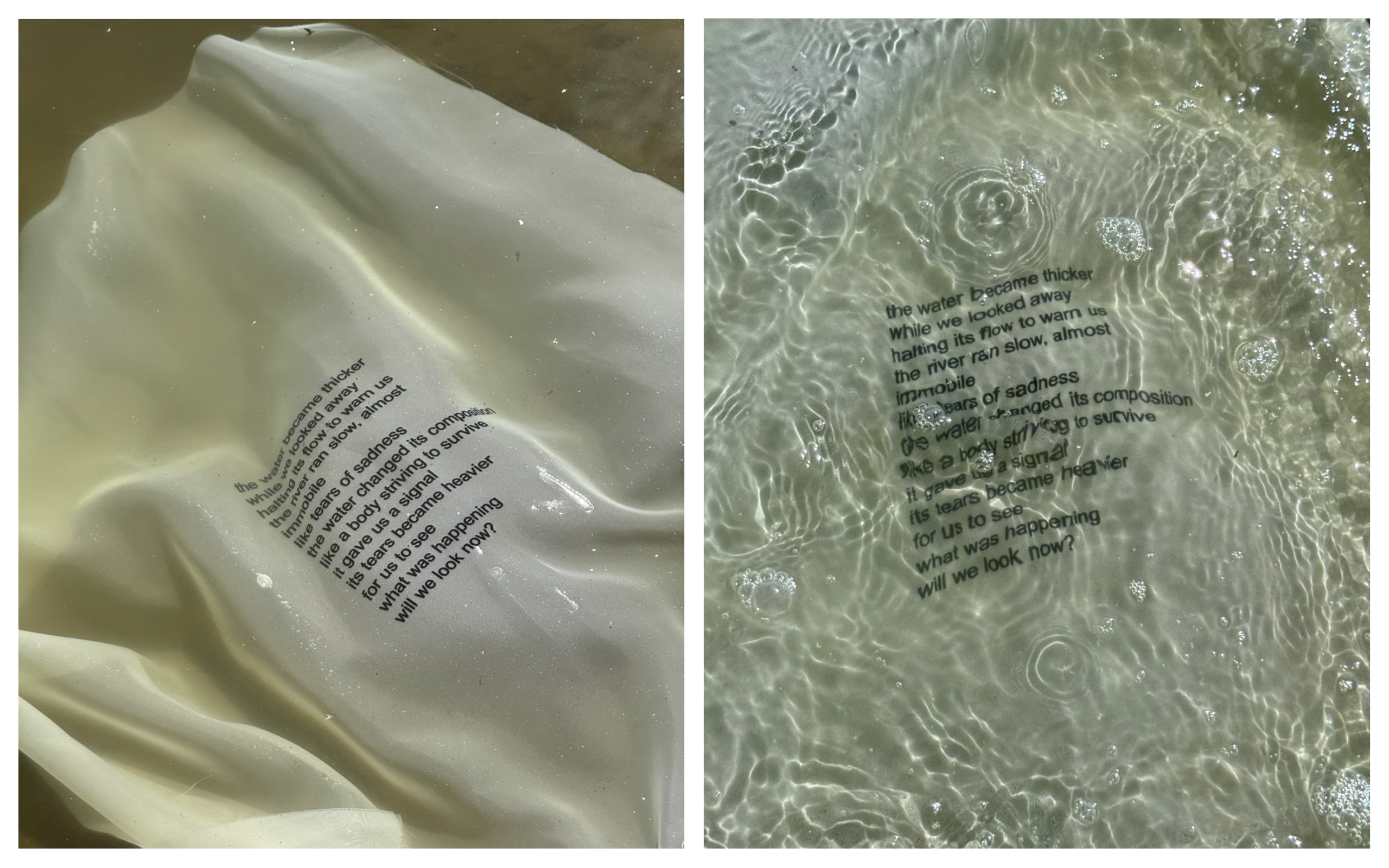

Angela, for her part, makes the poem a floating body. She buries her words in the Los Angeles River, the river that was buried under concrete in the 1930s to silence it. But nothing truly falls silent. The water returns, corrodes, and invents new paths. Her Poems of Inner Water are acts of healing: the words no longer describe the water—they unite with it, they become it. It is a ritual, a science of trouble, a prayer.

Tu étais dans la rivière video by Kerid Wengilbert

I also observe the gestures of students like Kerid, who are exploring this language with their hands, their intuition, their still-raw trial and error—and I identify with them. Because hydrofeminism isn’t a doctrine; it’s a living practice, a fluid experience, reformulated with every drop.

And in my videos, I seek to capture what I call the underwater vibrations of the world. Resistance isn’t always a cry: sometimes it’s a wave, a caress, an ebb. Water gently rebels. It chooses its path. In Local Ebb, I say that we are these slow, thinking waves. That our memory flows through the cracks. That rebellion can be intimate, liquid, sensual.

There is no separation between the body and the river. My uterus is a lagoon. My skin is a delta. Our internal organs are made of ancient water—water that has already passed through glaciers, clouds, and our ancestors.

We are water archives.

Water is not inert. It is chemically expressive.

It carries not only oxygen and mineral salts, but also a molecular memory. In every river today, we find traces of pesticides, agricultural nitrates, endocrine disruptors, and micro plastics. In the Rhône River alone, recent studies show the presence of more than 140 identified chemical pollutants, some at concentrations above eco-toxic thresholds.

In France, according to the IFEN (French Environmental Protection Agency), more than 70% of watercourses are affected by diffuse pollution (nitrates, phosphates, drug residues). And globally, 80% of wastewater is discharged into nature without treatment.

It’s not just chemistry. It’s a form of language. A bioaccumulation: what water absorbs, sediments retain, plants metabolize, fish concentrate, and humans—especially women, through the food chain—carry it in their blood.

When Clémence dyes her fabrics with these waters, the colors tell the story of this invisible chemistry. Water imprints its own biography. It reveals imbalances, wounds: a slightly acidic pH, a high salinity level, a dull color—all clues, silent symptoms of ecological disruption.

Water acts as a witness. It speaks in numbers, particles, molecules. But also in hues, textures, and slowness.

When Angela lets her poems drift, she doesn’t abandon her words—she lets them be rewritten by the water. The ink dissolves, the paper slowly fades, the words become fluid. It’s a form of poetic osmosis, a transfer of meaning between the human medium and aquatic intelligence.

Hydrofeminism, for me, is a poetic science of connection. A way of saying that everything is relational, everything is circulation—the living, language, emotions, pollution. What we do to the river, we do to ourselves.

The river is not “out there”. It’s within us. In our blood. In our saliva. In our tears.

And if we truly listen, not with our ears, but with our skin, our rituals, our fibers, then perhaps the water will agree to speak to us again.

Not to serve us.

But to transform us.

Videos by Margaux Balloffet

1– Local Ebb and Feminist Resistance

This is not a step backward.

It’s a memory that persists.

A curve in the flow, a breath backward.

We are this local ebb,

these waves that gently disobey.

Not to break,

but to remind us that water chooses its paths.

That the dominant current is never alone.

That everywhere there are countercurrents that think,

that dream, that dig.

We are that.

A fluid resistance.

A slow force

An aquatic rebel.

2- Liquid Massage of the World-Sex

I skimmed the surface, where the pink light still pulses. Spiraling, I called the origin,

the hollow, the center. A female sex engraved in the liquid. A gesture of love, a

gesture of resistance. Water, too, remembers.

3- Intimate Magic

Magic pulses like the first cells of life.

A kaleidoscopic trance-dance.

A pink river that allows itself to flow through its intimate flow, allows itself to be traversed by inner glory, and allows itself to shine before the eyes of the world as a woman, creator of humanity and fluidity.

Leave a Reply