about the writer

Margherita Muriti

Margherita Muriti is an Italian artist and professor based in Paris, France. Her multidisciplinary practice—spanning photography, installation, video, sound, and textiles—explores the materiality of images and sensory perceptions as a way to reimagine relationships with the other-than-human world and the landscape.

Introduction

In a time of ecological urgency, revitalizing our relationships with the other-than-human world has never been more vital. The Kinship Series roundtable brings together artists, scientists, biologists, activists, and thinkers from diverse fields to reflect on the unique ways human practices can reveal and nurture the intricate web of reciprocal relationships that shape our world. To speak of a tree, a river, or a landscape is also to speak of the network of beings—human and other-than-human—that makes, surrounds, and sustains it.

Our human gestures, both personal and collective, hold the potential to uncover and deepen the relationships between beings. By widening our perception and attuning ourselves to the subtle languages that emerge from these interconnections, we open up new pathways of listening and responding to the living world.

This process involves rekindling bonds through sensitive, creative, and situated acts—gestures capable of fostering renewed attention, care, and presence. From these efforts, new alliances may arise, supporting and amplifying affinities between species and environments.

Ultimately, the notion of kinship invites us to imagine long-term forms of interspecies coexistence—futures grounded in reciprocity, solidarity, and mutual flourishing. These reflections call us to listen to the wisdom of the Earth and envision ways of living together that are collaborative, embodied, and deeply intertwined.

As part of this series, the Kinship with Trees and Forests roundtable is an invitation to explore practices that cultivate reciprocal relationships with trees and forest ecosystems. Through gestures of care—artistic, scientific, ritual—we deepen our understanding of these living systems and nurture new ways of relating to them.

Drawn from various corners of the world, the participants in this roundtable bring a rich diversity of perspectives, stories, and practices that celebrate trees as beings. Their personal and situated approaches offer unique ways of honoring trees, engaging with them not merely as symbols or resources, but as companions, teachers, and kin.

Such practices invite a shift in perception: from seeing trees and forests as inanimate, isolated entities to embracing a porous, relational understanding of them—as living beings shaped by, and inseparable from, the elements and other life forms with whom they co-create their environments. They call us to recognize trees as subjects entangled with us in shared relations.

By exploring these correspondences—between bodies, rhythms, and ecologies—we expand our capacity to respond to the world we live with, and to the fragile continuities that sustain life. Empathy becomes a vital energy in the weaving of these interspecies relationships.

As anthropologist Tim Ingold beautifully reminds us:

“Where does the tree end and the rest of the world begin? (…) Considering, too, that the character of this particular tree lies just as much in the way it responds to the currents of wind, in the swaying of its branches and the rustling of its leaves, we might wonder whether the tree can be anything other than a tree-in-the-air. Is the wind, then, not as intrinsic to the tree as its wood?”

Read The Kinship with Rivers here.

about the writer

Emilio Fantin

Emilio Fantin is an artist working in Italy on multidisciplinary research. He teaches at the Politecnico, Architecture, University of Milan, and acts as coordinator of the “Osservatorio Public Art”.

Emilio Fantin

Si sente la forza vitale dell’albero che esce dal suolo e, attraverso il seme, scorre lungo il tronco.

Alcuni anni fa, a Rafah, un mandorlo caduto, ci raccontò un sogno: la profezia dell’incendio della foresta.

Disse: voi siete coloro che possono trasformare la realtà in un incubo.

I rami le foglie la corteccia

brucia tutto

fuoco fuoco fuoco

il fumo nero si alza dal tronco

Le Querce ardono avvolte tra le fiamme

Un odore acre di legna bruciata si espande

La temperatura liquefa farfalle impaurite

corteccia contorta e frutta cotta

Tizzoni ardenti brillano, tra ceneri sparse

Un liquido nero scorre tra gas primordiali

un assordante sinfonia di crepitii tra braci scoppiate

la linfa ribolle tra rivoli di resina

i rami contorti neri come archi bruciati

Brucia tutto

fuoco fuoco fuoco

roveti ardenti scompaiono

piante fiori sublimano in fumo

lingue di fiamme illuminano il cielo.

È notte la luna si ritira

in cielo appare la striscia bianca

di un F35 ormai lontano.

Vogliono “ripulire” tutto, eliminare completamente i vecchi mandorli e i piccoli ulivi piantati di recente. Dopo aver bruciato quanto più possibile, hanno bloccato i canali che permettono l’accesso dell’acqua agli alberi. I pochi alberi sopravvissuti vivono accanto al resto della foresta bruciata, cercando di attingere acqua dalle poche gocce rimaste dall’ultima pioggia. Ciò che resta delle giovani piante si staglia contro il cielo come scheletri neri. Molte voci gridano allo scandalo, ma nessuno muove un dito. Da una parte bombardano per distruggere gli alberi, dall’altra negano l’accesso all’acqua.

https://naturaartis.blogspot.com/p/scorri-per-la-versione-italiana-some.html

Alcuni anni fa un ulivo ci raccontò la profezia dell’olio d’oliva

Disse: abbiamo un sogno

C’è un seme d’ulivo sull terreno.

Il seme penetra rapidamente nel terreno.

Il seme è pulito e lucido, ma terribilmente solo, ormai completamente separato dall’albero che lo ha generato, dall’alveo madre.

Per questo motivo, il seme d’ulivo disgrega la struttura molecolare e i flussi di energia.

È il caos, ma ciò permette al seme di ricevere le forze del cielo e della terra.

Improvvisamente il seme spinge verso il basso le radici e spinge verso l’alto il cotiledone dal quale emerge lo stelo che, attratto dalle forze del cielo, buca il suolo, vince la forza di gravità e si libra verso il sole.

Lo stelo cresce rapidamente.

Il suo colore è verde, quasi trasparente, la sua brillantezza riverbera la qualità più raffinata delle forze del cosmo.

Presto iniziano a spuntare alcuni rami con le loro delicatissime foglie.

Si sente la forza vitale dell’albero che esce dal suolo e, attraverso il seme, scorre lungo il tronco.

L’albero cresce, ma all’improvviso accade qualcosa di molto speciale: i rami si contorcono in figure drammatiche a causa del sacrificio del loro anelito al cielo.

Invece di salire, tutte le forze si dirigono verso’estremità dei rami, dove crescono le olive.

L’oliva è un simbolo di congiunzione tra terra e cielo: le sfumature del suo colore, che vanno dal verde al nero, ci ricordano non solo la terra, ma anche i misteriosi fossili che giacciono sotto il suolo.

All’interno delle olive c’è un succo dorato e trasparente che porta sole, calore e luce.

La luce illumina il seme e il seme genera luce e così per sempre. Gli alberi difendono e trasformano la terra in piantagione fertile. Gli alberi invitano tutte le persone a celebrarne la crescita, ad assaggiarne i frutti, a berne il succo. L’ombra delle foglie è sempre presente anche quando il sole è troppo forte, le radici sono sempre lì e bevono l’acqua dalla terra anche se il fiume è piccolo, le stelle sono sempre lì per indicare la strada nel buio della notte.

Il sogno diventa realtà: non più fuoco, morte, distruzione ma luce.

You can feel the vital force of the tree coming out from soil and, through seed, flowing along the trunk.

Some years ago, in Rafah, a fallen almond tree lying on the soil, told us a dream: The forest fire prophecy.

He said: you are those who can turn reality into a nightmare.

Branches Leaves Bark

Everything burns

Fire Fire Fire Black

Smoke rises from trunk

Oaks burn in flames

A bitter smell of burnt wood expands

The Temperature liquefies fearful butterflies

Twisted bark and cooked fruit

Burning embers shine between scattered ashes

A black liquid flows between primordial gases

A deafening symphony of crackles between broken embers

Sap boils between streams of resin twigs black as burnt arches

Everything burns

Fire Fire Fire

Burning bushes disappear

Plants and flowers sublimate in smoke

tongues of flames illuminate the sky

it is the night, the moon retreats

In the sky appears the white stripe of a Mig now far away

They wanted to “clean up” the place, completely eliminate the old almond trees and small olive trees that had recently been planted. After burning as much as they could, they blocked the channels that allow water access to the trees. The few surviving trees live alongside the rest of the burnt forest, trying to draw water from the few drops left over from the last rain. What is left of the young plants stands out against the sky in the form of skeletons. Many voices cry out in scandal, but no one lifts a finger. On the one hand, bombing to destroy the trees, on the other hand, denying access to water.

https://naturaartis.blogspot.com/p/scorri-per-la-versione-italiana-some.html

Some years ago, an olive tree told us: I have a dream. The olive juice prophecy.

There is an olive tree seed on the soil.

The seed goes quickly in the soil.

Actually, the seed is clean and polished but terribly alone, completely detached from the tree that generated him, cast out from the mother tree.

Because of that, the olive tree seed breaks the order of its molecular structure and fluxes of energy. That is chaos, but this chaos allows the seed to receive sky and earth forces.

Suddenly the seed pushes down roots, and pushes up cotyledon from which emerges a stem, which, attracted by sky forces, holes soil, wins gravity force, and hovers toward the sun.

Stem grows up quickly.

Its color is green, almost transparent, and its brilliance reverberates the finest quality of cosmos forces. Soon, some branches start to grow up with their very delicate leaves.

You can feel the vital force of the tree coming out from soil and, through seed, flowing along the trunk.

The tree grows up, but suddenly something very special happens: branches twist in dramatic figures due to the sacrifice of their yearning toward the sky. Instead of going up, all forces are directed to the edge of the branches, where the olives grow.

Olive is a symbol of conjunction between earth and sky: nuances of its color which go from green to black, remember us not only soil, but also mysterious fossils which lay under the ground.

Inside olives, there is a gold and transparent juice which brings sun, heat, and light.

Light illuminates the seed, and the seed generates light forever. The trees will defend and transform this soil into a fertile plantation. The trees will invite all people to celebrate the growth, to taste the fruit, and drink the juice. The shadow of the leaves is always there, even when the sun is too strong, the roots are always there and drink water from the earth, even if the river is small, the stars are always there to show the way in the darkness of the night.

The dream becomes reality: no more fire, death, destruction but light.

about the writer

Mary O’Brien

Mary O’Brien is a multi-disciplinary artist—a writer and sculptor who initiates the research and community engagement plans for Studio of Watershed Sculpture the practice she co-founded with artist Daniel McCormick. Using an aesthetic lens, the Studio creates restorative interactions on damaged lands and waters through a scientific trajectory.

Mary O’Brien

Outliving

Maybe the question should be this: will the tree remember what we did in order to live in its presence, for as long as our lives would allow?

This is a story of a 150-year-old maple tree that witnessed native peoples’ displacement, white settlement, logging, summer shacks, prohibition, hippies, rock band rehearsals, landslides, neglect, tech booms, and eventually became part of our family.

What are trees in a human’s life? And what are we to them? Many trees will live as long as several of our human lifetimes. Will they remember us, the infrastructure we create that crowds them, or our own nostalgic approach to living with them?

I have known a few significant trees in my life. A couple of them, I have been privileged to live alongside. When I was younger, I thought it was enchanting to live under a giant tree. And indeed, the massive Chinquapin Oak in my parents’ backyard was very special in our post-war tract neighborhood. It was, perhaps, one of the trees that loggers of the late 1800s left behind. No matter its age, it was huge and is still deeply seated in my memory.

For 35 years, my partner and I lived with a 175-foot-tall Big Leaf Maple tree, its canopy shading most of our house on a steep slope in the foothills of Northern California’s Mount Tamalpais. Our house is tucked up against the tree’s massive trunks—a cluster of 11 trees, woven together and supporting each other on the slope. Arborist estimates identify it as the largest of its species in the region. It resembled a miniature old-growth forest outside our window.

At our first introduction to this tree, we were naive. We felt the tree belonged to us. It didn’t take long to question that notion when a large branch fell and destroyed a section of our deck. An arborist, motioning in a gesture that animated the tree, told us the limb was reaching out to get more sun. Eventually, the limb got tired of stretching and detached. We started pruning. Regularly.

The tree grew fast. Constant pruning made the tree safer, even if it did render it into the shape of a large bouquet of flowers choked at the bottom by the narrow distance between our house and the neighbors’. For over 30 years, the cluster of 11 trunks grew healthy with a full canopy and strong branches. It filled the windows of our dining room with the outdoors. It became the backdrop of family gatherings and serious discussions. Maple leaves on the kitchen floor were a common sight. In the winter, the trunks bloomed with bright green moss, fluffy and wet. In the summer, a singular lower twig would fill with 12-inch-wide leaves brushing softly against our windows. It was like living inside a tree, and it kept us a bit wild. Eventually, we realized we belonged to the tree.

I want this tree to remember the best of us, though I know that’s not entirely within my power. Another intelligence has been speaking through this tree for over 150 years.

And now the tree is dying.

There are many and none, when it comes to causes—too much or too little rain, climate warming, old age, or all of them. More than a few of the high branches are showing signs of die-back. Mushrooms appear at the bases. Our wildfire prevention district declared it unsafe, and we made the tough decision to cut it down. I mourned the tree for months before the actual cutting.

A community grant assisted with the costs, and neighbors offered help in the form of parking, road clearance, and moral support. We chafed at the thought of creating a decaying stump field. This beautiful being needed a better end. We wanted a monument.

We left the tree with 20-foot high trunks standing tall, angled the tops, and sealed them with bright orange paint—the kind loggers use for clear-cutting. Much of the carbon that the tree stored for over 150 years is still sequestered in its massive trunks, as well as in beautiful furniture made from the cut logs by a local sawmill. We titled the effort Spears of Influence for the community it engaged and the tree that kept on giving. It is meant as an act of art and climate activism.

This spring, the edginess we felt during the years the tree was dying was replaced with hope and confidence. Always a possibility with deciduous trees, new shoots are sprouting from the ground, but near the cut tops, bright green buds are also pushing out. And suddenly we have an abundance of healthy leaves we could never see up-close when the tree was 175-feet tall. A canopy is growing in front of our windows. A family of house finches perch on the cut tops, claiming the area previously dominated by squirrels. An entire new environment is emerging. We are not sure yet if those delicate leaves and branches are going to come back next season, but it is certain that parts of this tree will have a new life.

So, maybe the question should be this: will the tree remember what we did in order to live in its presence, for as long as our lives would allow?

about the writer

Martina Artmann

Martina Artmann is a professor at the Weihenstephan-Triesdorf University of Applied Sciences and leads the Leibniz Junior Research Group URBNANCE (Urban Human-Nature Resonance for Sustainability Transformation) at the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development. Her work takes an interdisciplinary approach to studying cities as socio-ecological systems and exploring their potential to contribute to sustainable development.

Martina Artmann

“The Spirit of the Forest ― A Childhood Memory That Shaped My Relation with Nature and Research”

I would like to use this roundtable to apologize to the ghost of the forest for harming the plants—and to thank him for the mystical experience that shaped my values of kinship, respect, and care for the web of life.

Some time ago, a close sibling said to me that he couldn’t imagine what I actually do all day as a scientist. A fair question. Although I conduct research on urban human–nature resonance, most of my days are spent indoors, sitting at a computer: handling administrative spreadsheets, preparing lectures, applying for project funding, and writing papers. Ironically, my own daily experience with Nature is often quite limited—perhaps even alienated from the more-than-human world I study.

Still, for me, being in resonance with Nature is about more than simply being outdoors. Don’t get me wrong—I love being in forests and mountains and wish I could do it more often. However, what matters to me most is not the frequency of Nature visits, but the quality of the relationship we cultivate with Nature. It’s about recognizing more-than-human nature as a soulful, animated partner—someone we care for, listen to, and communicate with. However, how do we engage with these relational qualities not just intellectually, but as whole human beings in an accelerating and often numbing world?

When I received the kind invitation to this round table, I wondered how I could contribute. To reflect, I went on a hike in the mountains. As I entered the forest, childhood memories came rushing back. I was lucky to grow up in a small village right next to a forest in the south of Germany. As a child, I spent countless hours there, alone and with friends.

One hot summer day, some friends and I wandered into a dense area filled with plants we believed to be dangerous, carnivorous. Of course, this was southern Germany—no such plants exist there. But in our imaginations, it was our mission to destroy them. We stormed in with sticks, beating the plants. Then, suddenly, everything went silent. Without a word, we all froze and looked up into the conifer canopy. And there he was: the ghost of the forest. We felt him move through the trees, ordering us to stop and leave. In a flash, a group of kids burst into tears and sprinted out of the forest— over hill and dale and through stinging nettles —straight to my parents’ house, where we hid under the table. Once we’d calmed down, we tried to make sense of it. We all agreed: the forest spirit had protected the plants. Even now, writing about it, I get goosebumps. As an adult, I could rationalize it—group dynamics, imagination, fear. But the memory is vivid, and I know it shaped how I see forests today: as soulful, autonomous beings within a living web we relate to in multidimensional ways.

Over thirty years later, I feel privileged and grateful to dedicate my professional life to exploring how we can overcome anthropocentric worldviews and muted human–nature relationships. I understand science as the endeavor to depict and understand the big picture of the relations we hold with the world and all its segments. If research aims to reflect reality, it must not ignore the invisible and non-material dimensions. Therefore, I see the urgent need to re-integrate transcendent and spiritual connections with Nature. For this, we need tools beyond statistics or remote sensing—we need openness to shift our perspectives, an openness such as children have very naturally. This roundtable, I believe, is one such playground where we can explore how to overcome anthropocentric human-nature relations. A space where we can begin to see Nature not as a lifeless object but as a relative in the Earth family to which we all belong.

I would like to use this roundtable to apologize to the ghost of the forest for harming the plants—and to thank him for the mystical experience that shaped my values of kinship, respect, and care for the web of life. As a token of my gratitude, I would like to share a poem with you. I wrote this poem during a time when I was engaged in a workshop on shamanic energy work. Some might dismiss such practices as strange or esoteric—but for me, it was grounding and deeply clarifying. Just as mountains and forests are part of my physical home, these ancient practices brought me home on an energetic level through a shift in frequency. This frequency is vibrating and alive and feels peaceful, warm, clear, and full of vitality. It reminded me of our profound connection to the world—across time, space, the visible and invisible, the living and the dead. Remembering this can be a vital step in nourishing kinships with trees and forests. This poem didn’t come from my mind alone, but from another source informed by this resonating frequency. The words and pictures captured in this poem have flowed out of me without thinking about them. By connecting with these different forms of knowing that address our mind, body, and spirit, we can begin to build a truly relational paradigm for both science and society.

Inside me ‒ inside us

Talking with the deer and rabbits

Cooking with the moon and the stars

Flowing in being, vibrating with the divine feminine

Infinite power and wisdom in our veinsThe sparkle in my eyes shows of eternity

We are born in the light and by the fire

Facing the moon, Mother Earth in our womb

One out there in the forest with me and everything

Alone together with the entity of the magic energyGreen the frequency flows

From head to toe to the beat of the drum

In the circle the spiders dance

And weave their web of life

In resonance with the mystical world

Of fairies, goblins, animals, and stonesAll join in a song of cosmic tones

From the bellies and eyes sparkles the moss green diamond

Dips the night in the baptism

Of life full of lust and wildness,

Gentleness and goodness ‒ everything vibrates

Everything is, then, now and forever

Inside me – inside us

The original poem was written in German and can be read here: https://urbnance.ioer.info/blog/blog-essay5/index.htm

Acknowledgement

Martina’s work is supported by the Leibniz Best Minds Competition, Leibniz-Junior Research Group under Grant J76/2019.

about the writer

Laura Nova

Laura Nova is an artist, educator, and activator who lives and works on New York’s Lower East Side, connecting generations and diverse communities around public health and the environment. She is currently designing and teaching in the CareLab at The New School and an Urban Field Station Collaborative Arts fellow advocating for the care and longevity of humans and trees.

Laura Nova

Care as Kinship

We observe that caring for trees also cares for us, in a reciprocal relationship.

How can artists nurture relations of care between people and trees throughout the lifecourse? What difference do attention, play, and ceremony make in cultivating these relations? Here we share three projects led by artist Laura Nova, who collaborated with social scientist Lindsay Campbell, that are rooted in co-learning, and composition―composing music, movement, designs―all with a goal of strengthening intergenerational and interspecies ties.

Sounds for the Tree Hotel ― storytelling and music making

Sounds for the Tree Hotel explored sonic kinship between humans and the more-than-human world at M’Finda Kalunga Community Garden’s Tree Hotel—a London Plane Tree enveloped by English Ivy serving as habitat for birds and urban wildlife. This interactive listening event conducted with radio producers Sara Kramer and Nina Porzucki, used deep listening practices inspired by R. Murray Schafer and Pauline Oliveros to cultivate reciprocal relationships with our acoustic environment. The space was accessible to all; participants of all ages and abilities were able to drop in and take part in the event without any prior preparation.

Participants engaged in guided acoustic ecology exercises, closing their eyes to attune to layered soundscapes: natural sounds, human body rhythms, and technological frequencies. Through shared sound memories and collective discussion, we explored how caring for acoustic spaces parallels caring for the trees that sustain us. Framing the world as a continuous musical composition, we tuned into the garden’s symphony and co-created a concert together. This practice of listening with love demonstrated how acoustic awareness can deepen our kinship with urban ecosystems. Attuning to the tree’s perspective allowed participants to nurture the interspecies relationships that sustain all life within the garden’s contested yet vital canopy. This realized relationship was celebrated with improvised instruments and the garden sounds providing a concert for the trees and humans alike.

“Sounds for the Tree Hotel,” conducted on June 15, 2024, at the M’Finda Kalunga Community Garden, in the Lower East Side of NYC.

Tree Loving Care ― Public performance

Tree Loving Care was a street performance exploring kinship through embodied care practices, performed with Sara Koller, Michelle Kahane, and CareLab during Art In Odd Places: CARE Festival. We blended our expertise in art, design, education, and meteorology to address the care crises, fostering empathy and solidarity in public space. We transformed street trees along 14th Street into care stations, inviting participants to connect with urban trees while highlighting their ecological and social benefits.

The performance included experimental movement with tools used in street tree care, embodying trees through gesture, collecting trash, and eliciting haikus and tree wishes from passersby. We wrapped trees with cyanotype-printed ribbons displaying collected wishes like “Swaying in the breeze / Willows’ arms create a room / graceful, patient giants”. Street tree care became performance art, demonstrating how nurturing relationships between humans and trees can spark attention, inquiry, and joy. These practices inspire people to notice trees differently, cultivating the care that sustains interspecies kinship in urban environments.

There were multiple levels of involvement in the performance. Performers could join Zoom visioning meetings and attend practices before the date which helped connect the group together. There were performers of all ages–including a 6-year-old “sapling”, and they engaged the public throughout the performance―some people laughed, some nodded, and some wrote tree wishes or made a haiku.

“Tree Loving Care,” transforming street trees into care stations at the Art In Odd Places: CARE festival on 14th Street, October 18-20, 2024.

Salons and Co-Learning ― Photokinetic Stewardship

Photokinetic Stewardship workshops use movement, photography, and acts of care to create intergenerational kinship through a collaboration between Weinberg Senior Center and Seward Park Conservancy’s indigenous pollinator meadow. This four-part salon series introduces seniors to photography as a creative expression and nature documentation, fostering deeper connections with local ecosystems. Participants (many newcomers to photography) explore digital and alternative processes while engaging in environmental stewardship and fostering a deeper connection to the nature of Seward Park, which many already consider a second home.

The workshops have come to be after integrating and synthesizing a year of working, thinking, and learning together through the NaturePLACE Collaborative Arts Program, especially through collaborating with Lindsay Campbell and the Stewardship Salon model. Each salon begins with embodied introductions—sharing names alongside movements inspired by the meadow, observations of seasonal changes, or memories triggered by place. The introductions aim to ground participants in the physical space but also foster connection with each other so they can engage comfortably and wholeheartedly in the activities.

Workshop activities span movement composition and botanical collection, lighting techniques for nature portraits, cyanotype printing, and nature face collages using garden materials. Through hands-on learning, participants document the Seward Park Conservancy’s mission while strengthening community bonds. Sessions conclude with reflections on how photographic skills transform perception and deepen place-based connection. Echoing Cicero’s wisdom that “If you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need”, these workshops cultivate reciprocal relationships between seniors, photography, and the more-than-human world that sustains urban community life.

* * *

Overall, these practices help inspire people to notice, to pay attention, to laugh about trees, and we believe that this inquiry and joy can spark further interspecies kinship and care. We observe that caring for trees also cares for us, in a reciprocal relationship.

about the writer

Adrina Bardekjian

Dr. Adrina C. Bardekjian leads the Research and Engagement department at Tree Canada, driving strategic initiatives like the Canadian Urban Forest Network and the National Urban Forest Conference, as well as collaborating with diverse partners on a variety of research. She has contributed to numerous publications, created engaging short films, such as Women Branching Out, writes poetry to share her research with wider audiences, and co-created of the discussion series Where Women Choose to Walk: Paths to Improving Cities and Nature.

Adrina C. Bardekjian

Branches of Belonging

by Adrina C. Bardekjian

Come plant a tree, then walk with me

On trails that weave our ancestry —

Through orchards ripe with roots and dreams,

Where kinship knits our hope as teams.

Forests wide and oceans deep,

Are mirrored twins whose secrets keep,

Earth’s timelessness expounded by,

Diverse biomes that kiss the sky.

What does forest kinship mean to me?

It means childhood laughter — wild and free.

It’s sweet nostalgia in my aching core,

It’s climbing trees until my knees are sore.

It’s lullabies hummed in a swaying breeze,

Being cradled in branches with new stories.

It’s leaves, like tongues that speak of love,

And shade that shelters from high above.

Because forests are deeply human things —

They inspire art, and offerings.

Echo faith, hold grief, and mirror fate,

And as sentinels, for justice wait.

For our children, their enchantment lingers —

With bark beneath their painted fingers.

For us grown-ups, they are sacred space,

Where roots of hope and home, mean place.

Where generations sang and prayed,

In global cultures, born and made.

Where seeds of certain species sown,

Weave memory in stewards grown…

*****

The oak spreads wide, a presence grand

Its trunk a pillar in the shifting land.

Long limbwalks bridge to paths unknown,

As acorns fall in fierce winds blown.

The sycamore bent beside a stream

Connects us with the in-between —

Repelling harm and warding strife,

A gateway to the afterlife.

The apricot, in sunlit air,

Whose blossoms dance through Yerevan’s square.

In volcanic soil thrives within —

From its wood we carve historic hymn.

The walnut wise, protecting kin

From cries still raw that tear within.

Of ancient legends, tomes of lore,

Fertility and wisdom, at its core.

The baobab stands through arid earth,

A beacon of hope and new rebirth.

It’s broad trunk a refuge, a school, a room,

Where elders gather and directions bloom.

The hawthorn tree with thorns so long

Is woven deep in Celtic song.

Blossoms balance — yet move with care,

For unseen guardians wander there.

The maple tree, our northern pride

Its vibrant colours, new seasons guide.

With flowing sap at winter’s end,

We toast to health, both foe and friend.

*****

In urban parks or country lanes,

On boulevards or windowpanes —

Trees soften life, they give us peace,

Like leafy chants that never cease.

We plant them, climb them, mourn when lost,

Forget their worth, but not their cost.

Yet still they give us shade and air

A stalwart presence, always there.

And as our cities change and grow,

Let’s learn the trees our neighbours know.

A forest shaped by every race,

Where cultures grow in shared embrace.

So, come plant a tree and walk with me,

To raise a world more kind and free.

Where our children bond with roots together,

And faith in trees, our futures tether.

— Adrina C. Bardekjian, MFC, PhD (2025)

Many cultures have connections with trees that have been deeply woven into their traditions, stories, mythologies, and survival throughout history. Certain tree species are ascribed cultural values and symbolic functions; they provide and inspire, and offer meaning to people around the world. They offer opportunities for communities to bond and for children to learn and grow with nature. They are also a touchpoint for new immigrants to feel familiarity to their new home. This poem celebrates the evolving cultural diversity of people through our connections with trees, and how we can engage and grow vibrant, open-minded cities and communities.

about the writer

Mauricio Tolosa

Born in Chilean Patagonia, Mauricio Tolosa’s work unfolds from a singular question: how can humans regenerate their bond with plants—listening deeply, co-creating with them, and even following their lead? His creative process integrates writing, photography, resonant gardening, and vibrational explorations, fostering interdisciplinary collaborations across art, philosophy, and ecology in an evolving dialogue with the Kingdom Plantae.

Mauricio Tolosa

Je suis les arbres. Not because I wish to become something else, but because I remember I’ve always been part of them.

Je suis les arbres

In French, “je suis” can mean both “I follow” and “I am.” This duality is central to what follows, meditation on becoming with the trees.

For over a decade, plants have shaped my life and work. I create with them through poetry, photography, gardens, workshops, essences, and videos. A year ago, I came to Paris for an art residency. When people ask what I’m doing here, I answer: “Je suis les arbres”. The phrase often draws a smile, sometimes curiosity.

A Latin American

My South American roots influence how I interact with the natural world. One of Latin America’s most defining traits is the presence of nature on a scale very different from what one finds in Europe. Tropical and temperate forests, along with other kinds of untouched vegetation, cover about 60% of South America. This presence is not just visible; it’s visceral. Even in cities, the ancestral vegetal world seeps through the cracks—it is a living, breathing force, always ready to reclaim its space. As humans, we are not above or outside this world. We are in it, sharing the land with an ancient, patient life force that dwarfs us in age and scale.

Many Indigenous cultures—such as Aymara, Mapuche, Guaraní, and Maya—continue to live in tune with that force. Their traditions have withstood centuries of European rationalism and Christianity, surviving since the conquest of 1492. These cosmovisions persist in the Latin American collective unconscious, shaping our relationship with the more-than-human world. They offer a less rational, more magical, and sensory way of understanding life. The boundary between ourselves and the rest of the living world is more porous. We are more receptive to the presence and vibration of nature.

That kinship is more than a metaphor for me—it’s practice. I once spent five years with an apple tree. Day after day, I sat beneath it. I wrote, meditated, photographed, and listened. Over time, I began to sense its rhythm. I moved slower and breathed differently. I entered its time.

Spiritual traditions often emphasise the importance of being present—of living in the here and now. The “here” is tangible. But the “now”—that’s harder. Time isn’t just clocks and calendars. It’s cosmic, seasonal, cyclical, botanical. Plants live in layered tempos, revealing time not as something passing but as something unfolding.

Following a tree means stillness. And in stillness, awareness deepens, making room for heightened sensitivity and a deep connection with plants. One can see flowers open, hear the crackle of buds, or merge with a plant in a cloud of aroma. Shared consciousness with plants becomes clear. Senses sharpen, and new perceptions emerge—of energy, vibration, breath—revealing a more evident shared world. The boundary between observer and observed begins to dissolve.

“I follow the trees” becomes “I am the trees.”

This shift in being opens unexpected space. A different world perception emerges—one where we’re not outside looking in but already inside, already part. We stop standing apart from plants as separate, civilised humans and begin to feel how deeply entangled we are with everything living.

It’s not a theory—it’s a felt experience. Something quiet, sensory, relational. And from this, new ways of thinking and dwelling arise. The idea of “nature” as other falls away. We belong to a shared world. Trees and plants take root in us, and we root ourselves in them.

Je suis les arbres.

Not because I wish to become something else, but because I remember I’ve always been part of them.

Koki Atcheson and Heather L. McMillen

about the writer

Koki Atcheson

Koki Atcheson (she/her) – Koki is an avid crafter with interests in secondhand textiles, utilizing unwanted or invasive plant materials, and gathering with others to make things by hand. In Koki’s work with Kaulunani, the State of Hawaiʻi’s Urban and Community Forestry Program, she practices art and building relationships with trees and people to create bridges between spreadsheets and ʻāina.

about the writer

Heather McMillen

Heather McMillen is the Urban & Community Forester with the Hawaiʻi Department of Land & Natural Resources. She is also an affiliate faculty member of the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Management at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

The engagement with this video product echoes the personal commitment involved in reciprocating with trees and forests.

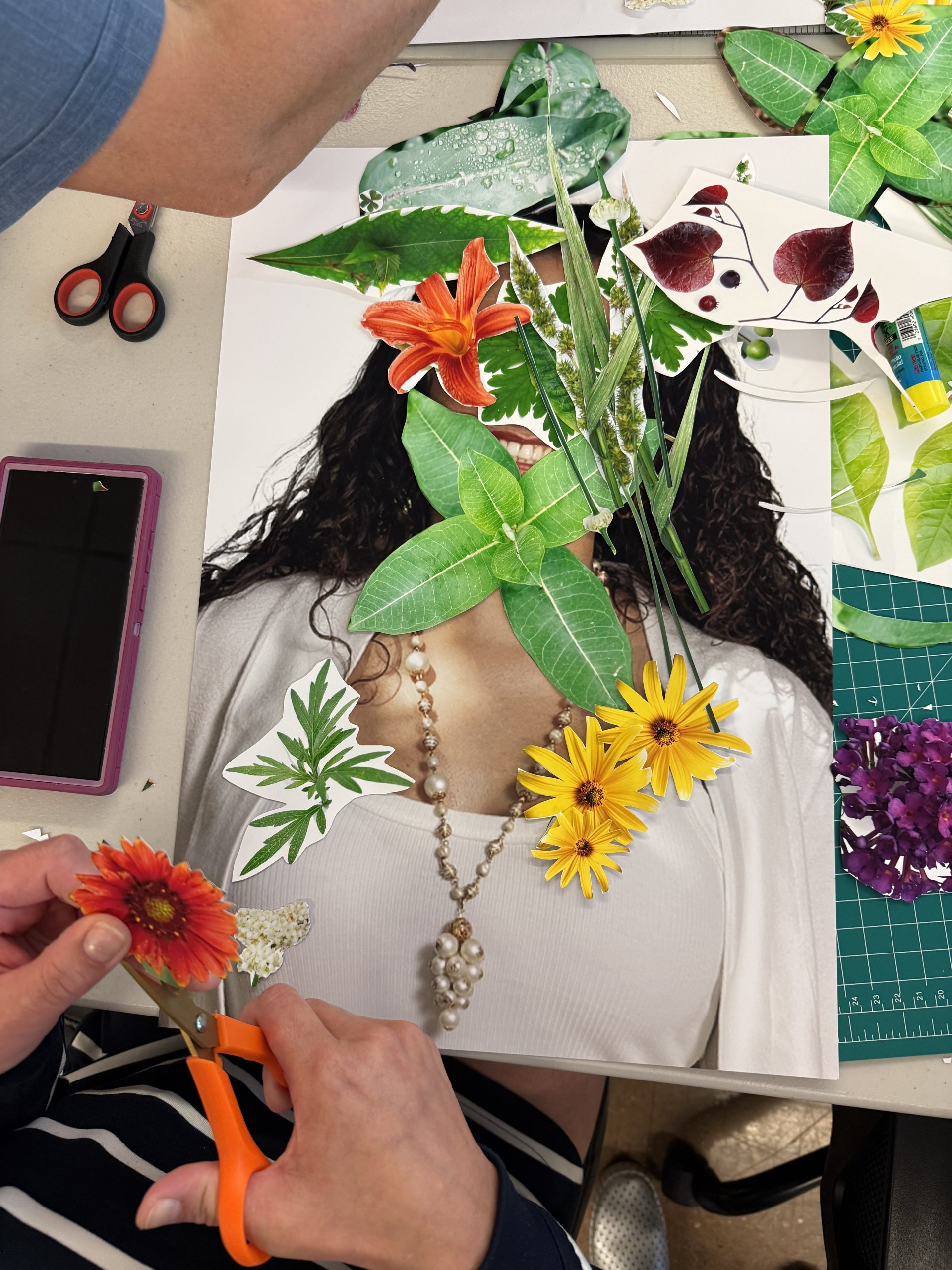

Kinship with Forests through Collage in the Conference Room.

The effort to succinctly express our Hawaiʻi-based group’s thoughts on reciprocal relationships with trees and forests quickly grew beyond the boundaries afforded by written text alone. Using collage as a novel and expansive container, a group of us gathered to connect ideas with text, visuals, and forms, to explore the prompt and tell stories more fluid than those with only words. Materials included paper otherwise bound for the recycling bin (recognizing the sacrifice of trees in being turned to paper), printed emails and favorite photos, illustrations, handwritten notes, invasive and native plant material, a resolution from this legislative session urging community co-stewardship of community forests, and more.

The viewer is asked to curate the meaning from the pieces and positioning of each collage. So, the engagement with this video product echoes the personal commitment involved in reciprocating with trees and forests. We are proud to submit a work that relies on paper and plant materials, and one that is irrefutably made by human hands.

about the writer

Flick Ferdinando

With 35 years of experience as a circus performer, street artist, educator, and director, Flick bring a rich background in physical theatre, comedy, and landscape installations. Holding an MA in Arts and Ecology, her work explores biophilic experiences that connect communities with nature. As a solo artist and collaborator, she creates performances and installation that engage with climate-conscious creativity, often set in both rural and urban landscapes. She is a gardener and treeworker. Her deep commitment to the planet and its natural world shapes every project she undertakes.

Flick Ferdinando

What if trees had their own union? What if the forest floor held not just roots, but resolutions? What if the oak chaired a council of ancient wisdom? The birch, a mediator. The cedar, a warrior poet.

The Tree Union

The people of Britain have a long and complex relationship with trees that runs deep. We revere them, celebrate them, and yet many cannot name them.

I myself am from an era where the message to “Save The Trees” was loud and clear. Over centuries, the land had been decimated to build and construct houses, roads, and ships. The mighty Oak, synonymous with our very being of this island, was felled to build glorious vessels that gave free travel to claim and colonise other lands. Ships returned not only with wealth and resources but with non-native species, imported to line British gardens and estates. Trees arrived like trophies, and people too; both used to plant, build, and serve the wealthy land owners’ vision.

This land lost out, became bereft of its soul. Its bold guardians.

Years later, the message is still the same, and I find myself as an artist and a steward of trees. Also, a person who explores their being and relationship to ecological systems and someone who cuts them!

It is a strange seat to occupy; reverence on one side, responsibility on the other. And yet, to sit in this place brings a broad perspective of the canopy of reciprocity. To prune a tree is not always to harm it. Sometimes, it is to give it breath, light, space to grow. The gesture is not one of violence but of care. A trimmed branch may give the tree more time on this earth and, in turn, give us the air we breathe.

But not all actions stem from such care.

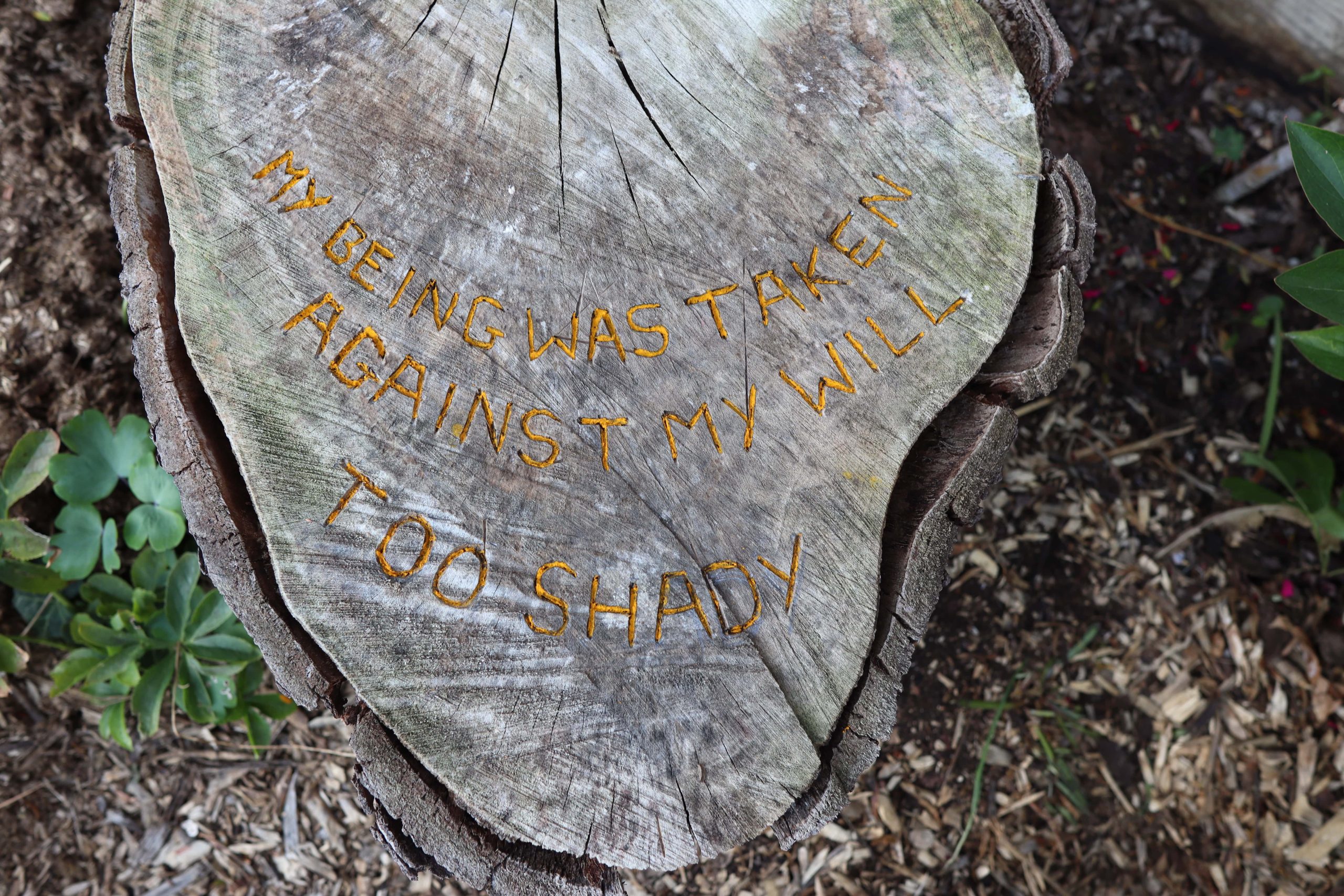

At the end of last summer, I moved into a new place. Before the move, I went to the house to observe it from the outside, to make a guess of the land that I would be tending. I observed a well-established eucalyptus tree on the land, near the boundary of the property. I was looking forward to meeting this tree, often derided as non-native, but to me, a tree of great beauty. When I finally moved in, the tree was gone. Cut down to a stump.

Later, I discovered that the neighbour next door had it felled. They didn’t want the shade in their garden. Their reasoning was simple. And yet their action cast a longer, darker shade over the quiet resilience of a living, breathing being.

As humans, we have jobs, all sorts of jobs, many of those jobs draw us away from the trees, the names of trees a distant necessity. In those jobs, there are unions to make sure the hierarchy within the human realm is kept in check, to make sure those hard workers have a voice and can call upon the stewards of their work to help when in need.

What if trees had their own union? What if the forest floor held not just roots, but resolutions? What if the oak chaired a council of ancient wisdom? The birch, a mediator. The cedar, a warrior poet.

We know that trees communicate with each other underground through their mycelium network. So, what if the eucalyptus could have sent a message to call on their steward to help with this negotiation? Imagine the eucalyptus filing a grievance for wrongful dismissal.

We forget the stories embedded in bark, the colour-enriched leaves. But what if we returned to a position of listening? What if we regarded trees not as a dressing for our gardens and streets but as co-workers in our shared task of planetary survival?

We should continue to hold a sacred agreement of give and take. We are deeply connected to trees for the survival of our current climate narrative. In my role as artist and tree steward, I hope to honour that agreement. When I cut, I try to cut with care, and, in this instance, with this work, I lay down some words that might give voice to the dear eucalyptus. Cut into the very eucalyptus that the neighbours shady behaviour brought to a swift end.

If the eucalyptus had had a union, maybe it would still be standing. Maybe it would have spoken, and maybe, just maybe, we would have listened.

about the writer

Marjolein van der Loo

Marjolein van der Loo is a Dutch curator, researcher, and artist whose practice explores ecological relationships, collective learning, and embodied knowledge. She develops long-term, collaborative projects engaging with plants, landscapes, language, and feminist and decolonial thought.

Marjolein van der Loo

To drink Linden tea is not just to soothe the nerves. It is to step into a lineage of listening. Of honoring. Of remembering. It is to take part, however briefly, in the linden tree’s quiet campaign for memory.

In Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the narrator dips a Madeleine into a cup of tea and is suddenly overcome by an involuntary memory—a moment so vivid it seems to resurrect an entire world. While it is the small cake that gets most of the literary attention, it was linden tea—tilleul—into which it was dipped. Warm, fragrant, and subtle in taste, the tea becomes the true alchemical agent, transforming the present into a portal to the past.

The linden tree, quietly lining city streets and standing in the corners of parks, carries within it an ancient kind of presence. Its golden blossoms announce early summer with a scent that seems half floral, half memory. To walk beneath a linden in bloom is to feel something stir—a softness, a slowness, perhaps even a recognition. It is not hard to imagine that the tree means for this to happen.

Long before its urban popularity, the linden held sacred status across Europe. Among the Celts and Germanic peoples, it was seen as a feminine force—wise, protective, and just. Villagers gathered beneath its branches for refuge, for justice, and for decisions. It was a place not only of shade but of clarity, as if the tree itself offered guidance, rooted in time.

The linden’s blossoms, harvested just as summer begins, are not merely beautiful or useful—they are emissaries of memory. Their scent lingers in the mind. Their tea soothes not only the body but the heart. Known for calming anxiety and aiding sleep, they seem to soften the edges of life, making space for reflection. Perhaps, as Proust’s scene suggests, they do more than comfort—they awaken. They remind.

In this way, one could speculate that the linden tree does more than passively exist. Through its generous offerings, it may actually want us to remember. To taste, to feel, to tell. What if the tree’s deeper purpose—beyond beauty, beyond medicine—is to help us carry memory forward? Not just our own, but that of places, of kin, of relationships with the more-than-human world. Could the subtle work of its blossoms be to keep stories alive?

Though now more common in urban landscapes, the linden’s roots stretch back into old-growth forests, where they once thrived. In places like the Savelsbos and Vijlenerbos in the Netherlands, one can still find ancient lindens standing as green elders. Their decline, traced to early agricultural practices and forest clearing during the Neolithic, parallels the shift from foraging to farming, from deep ecological relationships to control and ownership. And yet, even in cities, the linden persists. It has adapted. It has not given up its vocation. Its scent still travels with the breeze in June, inviting us to pause, to listen, to remember.

To harvest linden blossoms—carefully, respectfully, as Robin Wall Kimmerer describes in her “honorable harvest”—is to re-enter a relationship. It is to acknowledge the plant not just as a resource, but as a partner. A partner in healing, yes—but also, perhaps, in storytelling.

Linden tea, when brewed slowly and sipped in stillness, may not always trigger Proustian floods of memory. But it does open a door. A warmth in the chest. A sudden thought of someone long gone. A quiet knowing. In that golden cup lies a gentle voice that says: remember.

In a time when so much urges us to forget, to move fast, to start over, the linden offers something else. A slowing down. A rooting in place. A quiet advocacy for continuity—not as nostalgia, but as grounding. As presence. As the weaving of past and present into something more whole.

To drink linden tea is not just to soothe the nerves. It is to step into a lineage of listening. Of honoring. Of remembering. It is to take part, however briefly, in the linden tree’s quiet campaign for memory.

Leave a Reply