Nous vous invitons à embarquer pour un voyage artistique qui connecte l’urbain et le rural dans un désir de créer des formes artistiques qui nous relient à la nature locale // Join us on this artistic journey between urban and rural, featuring art and actions that connect us with the larger landscape to which our cities belong.

LES SAVOIRS VIVENT DANS LA TERRE

KNOWLEDGE IS IN THE LAND

a story by Carmen Bouyer

CHER.ES LECTEUR.ICES,

Soyez les bienvenu.es! Nous vous invitons à embarquer pour un voyage artistique conté par l’artiste Carmen Bouyer et diffusé ici grâce à l’équipe de The Nature of Cities. Cette histoire connecte l’urbain et le rural dans un désir de créer des formes artistiques qui nous relient à la nature locale. Cette courte histoire est une invitation à imaginer nos propres façons d’écouter et de nous connecter avec les lieux que nous habitons. Nous suivrons ici l’histoire de l’artiste qui revient en France, en région parisienne, après des années de vie urbaine à l’étranger. Comme beaucoup de citadin-es dans les villes d’Europe occidentale, Carmen avait le sentiment que les cultures locales de reliance avec la terre avaient été perdues depuis longtemps. Elle se sentait désorientée, attirée par des pratiques lointaines qui honorent la nature, mais consciente de la violence de l’appropriation culturelle dont celles-ci souffrent. Elle a dû regarder d’où elle venait: du centre de Paris. Les mots qui suivent l’ont magnifiquement aidé. C’est lorsque Robin Wall Kimmerer, mère, scientifique, professeur émérite et membre de la nation Citizen Potawatomi a déclaré dans une interview à la radio For The Wild:

La connaissance elle-même peut disparaître du peuple mais elle n’est pas perdue car cette connaissance réside en fait dans la terre. C’est la terre, nos rivières, les plantes et les animaux qui vont nous enseigner et c’est notre relation avec eux qui va nous permettre d’apprendre.”

introduction

de retour au pays

APRÈS SEPT ANNEES PASSÉES A L’ÉTRANGER

Entre les Etats Unis d’Amérique appelés Turtle Island par certaines Nations indiennes et la Turquie, je rentre à Paris en France, ma ville natale. C’est un profond chamboulement. Au contact des personnes magnifiques qui ont croisé mon chemin j’ai compris l’importance de connaître la nature des lieux où l’on a grandi. C’est pour tisser profondément ces liens que j’ai choisi de m’immerger dans la nature dans la forêt de Fontainebleau au bord de la Seine à une heure au Sud de Paris, la ville où j’ai grandi, et de m’y installer. Le village s’appelle Samois-sur-Seine, paisiblement accroché à un coteau en bord de fleuve, on peut s’y baigner le matin, et l’après midi se promener dans les bois. Aller vers un en-sauvagement comme introduit par l’éco-philosophe Joanna Macy, une fusion avec le paysage. C’est ainsi que j’ai installé mon atelier et ma vie en bord de rivière et de forêt.

back home

AFTER SEVEN YEARS LIVING ABROAD

Between the United States / Turtle Island one of the Native American term and Turkey or Türkiye, I return to Paris in France, my native city. It is a profound change. In contact with the magnificent people who crossed my path, I understood the importance of knowing the nature of the places where one grew up. It is to deeply weave these links that I chose to settle in nature in the forest of Fontainebleau on the banks of the Seine, an hour South from Paris, the city where I grew up. The village is called Samois-sur-Seine, peacefully clinging to a hillside on the banks of the river, a place where you can bathe in the morning and walk in the woods in the afternoon. A greening of the self as introduced by Joanna Macy, a melting into the landscape. This is how I set up my studio and my life on the river banks by the forest.

sagesses

JE SUIS RENTRÉE AU PAYS

Imprégnée des spiritualités et sagesses liées à la terre rencontrées au cours de mon long séjour. Des enseignements amérindiens du nord-est et du sud-ouest de Turtle Island, des nations Haudenosaunee, Algonquin, Poté Watami, Diné et Lakota, au cosmopolitanisme New Yorkais, à la spiritualité mésopotamienne et soufi rencontrée dans la région égéenne de la Turquie, je me suis sentie profondément nourrie par les façons d’être des personnes que j’ai rencontré. De cette grande période d’introduction aux différentes cultures de ces régions, j’ai réalisé l’importance de me connecter aux pratiques culturelles qui maintiennent et honorent la connexion intime avec la Terre Mère ici aussi en Europe, en France mon pays d’origine, et plus spécifiquement dans le Bassin parisien où j’ai grandi en tant que parisienne. Ici, les voix des personnes détentrices de connaissances écologiques traditionnelles ont été réduites au silence, souvent depuis des siècles, par diverses formes de honte, d’interdiction et parfois d’extermination au nom de la religion ou d’une idée de la modernité. Des pratiques violentes à l’encontre des gardiens des sagesse de la terre qui ont été imposées à l’étranger par la colonisation des Européens.

Aujourd’hui, alors que les mouvements de décolonisation des idées et des pratiques prennent plus d’ampleur, de plus en plus de personnes s’intéressent aux traditions et innovations locales qui tentent de restaurer et de régénérer des patrimoines culturels situés respectueux de la nature. En m’installant dans ma nouvelle vie dans le village de Samois-sur-Seine près de Paris, j’ai plongé dans un espace d’introspection. J’ai fait des recherches sur les écosystèmes spécifiques du bassin parisien, les modes de subsistance traditionnels associés ainsi que les univers symboliques associés à ces lieux. Une région du monde si familière et dont j’avais pourtant tant à apprendre. Archéologie d’une indigénéité francilienne, et traces de pratiques culturelles dans la tendresse et le respect de la terre… C’est cette histoire dans laquelle je puise pour développer mon parcours artistique et que je souhaite vous raconter aujourd’hui. Merci d’être là. Embarquons.

wisdoms

I CAME BACK TO MY COUNTRY

Full with the land-based spiritualities and wisdoms encountered during my long journey abroad. From the Native American teachings of the Northeast and Southwest of Turtle Island from the Haudenosaunee, Algonquin, Poté Watami, Diné, and Lakota Nations, to New York’s cosmopolitanism, to the Mesopotamian and Sufi spirituality encountered in the Aegean region of Turkey, I felt profoundly humbled and nurtured by the ways of the people I could encounter. From this great period of introduction to different cultures, I realised the importance of connecting with cultural practices that maintain and honour the intimate connection to the great whole of Mother Earth here too in Europe, in France my home country, and more specifically in the Parisian Basin where I grew up as a Parisian. Here the voices of people holding traditional ecological knowledge have been silenced sometimes for centuries through various forms of shaming, interdiction and at times extermination in the name of religion or of an idea of modernity. Violent practices against wisdom keepers of the land that were brought abroad through colonization by Europeans.

Today, as more movements focus on the decolonisation of ideas and practices, an increasing number of people are paying attention to local traditions and innovations that are restoring and regenerating geographically specific nature-honouring cultural heritages. While settling into my new life in the village of Samois-sur-Seine, I plunged into a space of introspection and research of the Parisian basin ecologies and traditional ways of subsistence. The location was favourable, the village being ideally situated between the largest forest in the region, that of Fontainebleau, and the river Seine just upstream from Paris. A region of the world so familiar and yet of which I had so much to learn from. Archaeology of a Francilien indigeneity, and traces of cultural practices in tenderness and respect of the earth… It is this history in which I draw in order to develop my artistic path and that I wish to tell you today. Thanks for being here. Let’s embark.

acte I — enracinement et régénératioN

rootedness and regeneration

temps géologiques

CONNAITRE LES TEMPS ANCIENS ME RELIE A LA TERRE

C’est en m’intéressant aux évolutions géologiques et préhistoriques de la région parisienne, que j’ai pu trouver les histoires de reliance à la terre les plus puissantes. Toucher du doigt les temps anciens de cette terre me bouleverse, ils renversent ma perception étroite du monde en l’élargissant fantastiquement, une expérience qui m’ancre dans une humilité calme et ancestrale. C’est comme si le temps m’accueillait, si minuscule, au creux de ces mains d’infini.

Imaginez il y a des milliers d’années, le temps d’avant, bien avant la construction de la ville de Paris. S’étendait ici un océan dont on trouve encore les larges étendues de sable parmi les arbres de la région et sous les pavés de la ville immense. Je perçois la végétation mouvante au fil des temps, la grande épopée nomade des arbres. Imaginons la dernière ère glaciaire, l’ère froide du genévrier, du pin et du bouleau de la Pléistocène, qui en migrant vers le Nord alors que les climats se réchauffent laisseront la place au chêne, à l’orme, au hêtre, feuillus des temps doux de l’Holocène que nous connaissons aujourd’hui. Les steppes où erraient les troupeaux d’élans, se transforment en forêts où règnent les cerfs et les sangliers. Des temps océaniques, il reste de larges chaos rocheux, grès intemporels qui modèlent l’espace de façon surréaliste dans toute la forêt de Fontainebleau.

deep time

KNOWING ANCIENT STORIES CONNECTS ME TO PLACE

It was when I got interested in the geological and prehistoric histories of the Paris region that I was able to find the most powerful stories of connection to the land. Getting to know the ancient times of this earth moved me. It reversed my narrow perception of the world by enlarging it fantastically, an experience that anchored me in a calm and ancestral form of humility. It is as if time welcomed me, so tiny, in the palms of its infinite hands.

Imagine thousands of years ago, the time before, well before the construction of the city of Paris. An ocean stretched out here, and you can still find wide stretches of sand among the trees of the region and below the city pavements. I perceive the vegetation moving across times, the great nomadic experiences of trees. Let’s imagine the last ice age, the cold era of juniper, pine and birch of the Pleistocene, which by migrating northward as the climate warms up will give way to oak, elm, beech, hardwoods of the mild Holocene that we know today. From the steeps where roamed the elks, comes the forested times were the stags and the wild boars ruled. From the oceanic times there remains large rock formations, timeless sandstone that shapes the Fontainebleau forest’s landscapes in surreal ways.

La forêt de Fontainebleau est le premier espace occupé par des groupes humains dans cette steppe qu’était alors l’île de France.

The Fontainebleau forest is the first space occupied by human groups in this steppe that we now call l’Ile de France.

S’y niche de nombreux rochers ornés, témoins magnifiques d’une empreinte humaine artistique sur le paysage. L’art rupestre de la région Ile de France se développe particulièrement au Mésolithique (9500 à 5500 avant J.-C). Plus de 2000 abris ornés on été inventorié par l’association locale de sauvegarde de l’art rupestre, le GERSAR. Ceux-ci sont gravés de motifs géométriques répétitifs (stries, quadrillages) dont la symbolique a été interprétée de divers façons selon les époques: imitation des structures géométriques des huttes, traces de rites répétitifs, etc. Nous en parlerons plus tard. Cet ensemble rupestre, totalement méconnu des parisiens, est enfaite le second plus important en France après la Vallée des Merveilles situé dans l’arrière pays de Nice dans le Mercantour.

Ces gravures nous révèlent un monde vibrant, où la culture s’est mêlée au paysage de façon totale. Ces marques imprégnées dans le rocher, comme une peau magique striée, elle nous parle de se qui se qui se passe sous la notre, dans l’espace magique de notre être.

“La montée en puissance de l’empire a été en partie facilitée par la déracinement des mythologies locales. Alors que l’effondrement du climat s’aggrave, un retour à la mythologie multi-espèces pourrait bien être ce qui nous sauvera.“

écrit Sophie Strand dans son article Rewilding Mythology. Quelles mythologies profondément ancrées dans le territoire pouvons-nous faire vivre, ici dans la région de Paris?

There, numerous ornamented rocks can be found, magnificent witnesses of an artistic human imprint on the land. Rock art in the Ile de France region developed particularly in the Mesolithic period (9500 to 5500 BC). More than 2000 decorated shelters have been inventoried by the local association for the protection of rock art, the GERSAR. These are engraved with repetitive geometric motifs (striations, grids) whose symbolism has been interpreted in various ways depending on the period: these include the imitation of geometric hut structures, traces of repetitive rites, etc. We will talk more about it later. This rock group, totally unknown to Parisians, is in fact the second most important in France after the Vallée des Merveilles in the hinterland of Nice in the Mercantour.

These engravings reveal to us a vibrant world, where culture has blended with the landscape in a total way. These marks impregnated in the rock, like a magical striated skin, speak to us of what is happening beneath our own, in the magical space of our being.

“The rise of empire was in part facilitated by the deracination of local mythologies. As climate collapse worsens, a return to multi-species mythmaking might just be what saves us.”

writes Sophie Strand in her article Rewilding Mythology. What mythologies deeply rooted in the territory can we bring to life here in the Paris region?

femininite ancestrale

ACCUEILLIR LES CYCLES DE REGENERATION

En retournant aux traces les plus anciennes de mythe dans la région parisienne, j’ai trouvé celui d’une puissante déité féminine immanente, celle de la mère nature, qui préside aux cycles de mort et de renaissance. En effet, les grottes striées de motifs de la forêt de Fontainebleau ont été interprétées par l’archéologue américaine d’origine lituanienne Marija Gimbutas (professeur d’archéologie Européenne à l’Université de Californie) comme faisant référence à une telle divinité, dans son livre culte “Le Language de la déesse“:

“Des carrés avec des dessins de filet ou des lignes parallèles, ou marqués d’une croix ou d’un X, qui se présentent sous forme de sablier, sont gravés sur les parois des grottes post-paléolithiques. Environ deux mille grottes contenant de telles gravures sont inventoriées en France; elles sont concentrées dans la région parisienne, dans les aires de Seine-et-Marne, de Seine-et-Oise et du Loiret (König 1973). Certaines sont connues sous le nom de “grottes aux fées”. Elles évoquent une matrice ou un utérus, et étaient probablement aussi sacrées aux temps préhistoriques que les grottes similaires abritant des puis sacrés le sont aux périodes historique et moderne (…) Ces lieux mystérieux sont sûrement consacrés à la déesse-celle qui porte l’eau vivante, celle qui donne la vie.”

Imaginer ces centaines de grottes striées qui peuplent la forêt comme autant d’utérus de femmes enceintes, espaces de transformation rituel, m’a beaucoup émue. Un mythe certainement, mais aussi une espace imaginaire que j’invitait à nourrir mon présent et mon art.

Dans son ouvrage, Gimbutas propose une analyse approfondie des motifs géométriques que l’on trouve en Europe durant le Mésolithique et au début du Néolithique, période qui précède l’hégémonie des cultures patriarcales basée sur l’agriculture et l’élevage. Cet “alphabet métaphysique” de motifs est associé selon elle au culte de l’essence féminine du monde. Cette religion de la vieille Europe qui honore “tant l’Univers – corps vivant d’une Déesse-Mère-Créatrice – que tout ce qui en lui participe de sa divinité” selon les mots de Joseph Campbell qui préface le livre.

“Le concept de régénération et de renouveau est peut-être le thème le plus remarquable et le plus dramatique que nous percevons dans ce symbolisme. Il semble plus approprié de considérer toutes ces images comme les aspects d’une seule Grande Déesse avec ses fonctions essentielles – donner la vie, donner la mort, assurer la régénération et le renouveau. L’analogie est évidente avec la nature elle-même; à travers la multiplicité des phénomènes et la continuité des cycles dont elle est faite, on reconnait l’unité fondamentale de la nature.”

ancestral femininity

WELCOMING REGENERATIVE CYCLES

Going back to the earliest traces of myth in the Paris region, I found that of a powerful immanent female deity, Mother Earth, who rules over the cycles of death and rebirth. Indeed, the patterned caves of the Fontainebleau forest have been interpreted by Lithuanian-born American archaeologist Marija Gimbutas (professor of European archaeology at the University of California) as representing the interior of the womb of such a deity, in her iconic book “The Language of the Goddess, Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilisation”:

“Squares with net patterns or parallel lines, or marked with a cross or an X, which appear in the form of an hourglass, are engraved on the walls of post-Paleolithic caves. About two thousand caves containing such engravings have been inventoried in France; they are located in the Paris region, in the areas of Seine-et-Marne, Seine-et-Oise and Loiret (König 1973). Some are known as “fairy caves”. They evoke a womb or uterus, and were probably as sacred in prehistoric times as similar caves containing sacred objects are in historical and modern times (…) These mysterious places are surely dedicated to the goddess-she who holds the living, life-giving water.”

Imagining these hundreds of striated caves that populate the forest like so many wombs of pregnant women, spaces of ritual transformation, moved me a lot. A myth certainly, but also a fertile imaginary space that I invited to nurture my present and my art.

In her book, Gimbutas offers an analysis of the geometric patterns found during the European Mesolithic and early Neolithic transition, a period that marks the arrival of patriarchal cultures based on agriculture and livestock. This “metaphysical alphabet” of geometric shapes found throughout the continent between 7000 and 3500 BC is associated with the cult of the feminine essence of the world. This old European religion honours “both the Universe – the living body of a Goddess-Mother-Creator – and everything in it that participates in her divinity” in the words of Joseph Campbell who prefaces the book.

“The concept of regeneration and renewal is perhaps the most remarkable and dramatic theme we perceive in this symbolism. It seems more appropriate to see all these images as aspects of one Great Goddess with her essential functions – giving life, giving death, ensuring regeneration and renewal. The analogy is obvious with nature itself; through the multiplicity of phenomena and the continuity of cycles of which it is made, one recognises the fundamental unity of nature.”

Alors que mon immersion de le temps long de ma région continuait, à la recherche de références artistiques ancestrales qui honorent la vie, j’ai été frappé par une grande découverte. La plus ancienne gravure trouvée dans la forêt de Fontainebleau montre un pubis féminin entouré de deux chevaux. Dite “de la Ségognole“, elle est littéralement la “grand-mère” de la manifestation humaine dans la forêt, car cette gravure a été réalisée 10 000 ans avant toutes les autres. Elle a environ 20 000 ans et est contemporaine des grottes de Lascaux. Le plus touchant est que cet oeuvre d’art première est aussi une fontaine, elle est dynamique. Les anciens de l’époque ont travaillé la roche pour permettre à l’eau de s’écouler à travers ce symbole du sexe féminin.

Cette oeuvre d’art si primordiale m’a remplie de joie, me faisant accueillir mon féminin de façon renouvelé, fier de sa force. Quelle ressource vive que cet héritage gravé, dans une région du monde où la puissance transformatrice des femmes a trop longtemps été bridée. C’est accompagnée de ces mythologies associées à un féminin ancestral que je me suis plongé plus en avant dans des formes d’exploration artistiques du monde et de moi-même. Ecoutant mon instinct, dans mon atelier et dans la nature, j’ai plongé dans un univers multi-sensoriel, sans normes, en couleurs et en rythmes. Je me reliais alors au mouvement éco-féministe à travers des actions spontanées, reliées à la terre, à l’eau et à mon corps que je percevait alors comme un grand tout sans séparation, ample, immense, et sans fin.

As my immersion in the long time of my region continued, in search of ancestral artistic references that honour life, I was struck by a great discovery. The oldest engraving found in the Fontainebleau forest shows a female pubis surrounded by two horses. This engraving “de la Ségognole” is literally the “grand mother” of human manifestation in the forest, it was made 10,000 years before all the others. It is about 20,000 years old and is contemporary with the Lascaux caves. What is most moving about this early art form is that it is also a fountain, it is active. The ancients worked the rock to allow water to flow through this symbol of female sex.

This primordial work of art has filled me with joy, making me welcome my feminine in a renewed way, proud of its strength. What a living resource this engraved heritage is, in a region of the world where the transformative power of women has been curbed for too long. It was with these mythologies associated with an ancestral feminine that I plunged further into artistic exploration of the world and of myself. In my studio and outside in nature, listening to my instincts, I plunged into a multi-sensory universe, without norms, in colours and rhythms. I connected myself then to the eco-feminist movement through spontaneous actions, connected to the earth, to water and to my body that I could then perceive as a great whole without separation, ample, immense, and endless.

rythmes du paysage

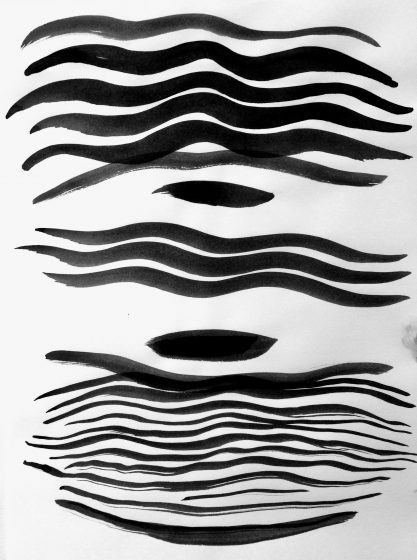

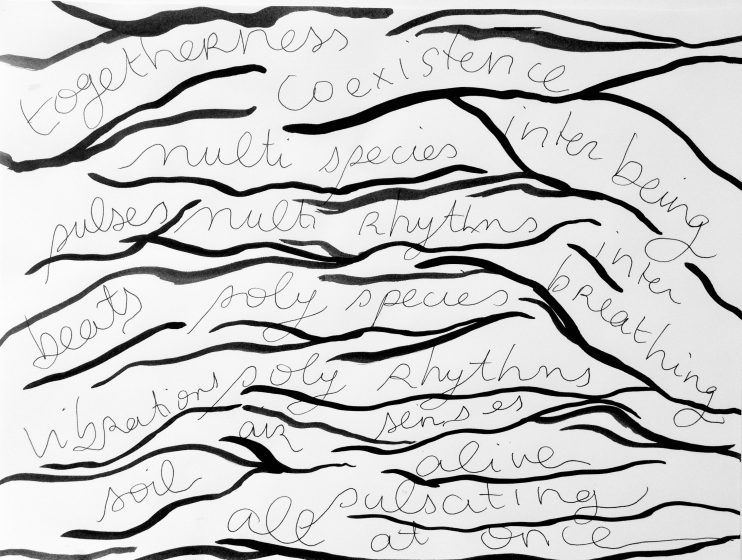

ECOUTER LES PULSATIONS DU MONDE

Les pulsations cycliques du village où j’ai vécu au bord du fleuve, me sont sont devenues évidentes à force de promenades au bord de l’eau, en forêt, et le jour et la nuit, au rythme des saisons, des migrations d’oiseaux, de l’éclosion des fleurs et de la chute des feuilles. Ces pulsations cycliques rejoignant mes cycles féminins synchronisé avec la lune, et l’intime vibration créée par les poly-rythmes de ma respiration conjointe aux battements de mon cœur. Tout vibre, tout tambourine, tout est animé. Je me suis mise à l’écoute le chant subtile des enchaînements de rythmes dans la nature en imaginant qu’ils pourraient nous guider vers une connaissance plus intime de son harmonie vitale.

rhythms of the landscape

LISTENING TO THE PULSE OF THE WORLD

The cyclical pulsations of the village where I lived by the river became evident to me through my walks by the water, in the forest, during the day and at night, with the rhythm of the seasons, the migrations of the birds, the blossoming of the flowers and the falling of the leaves. These cyclic pulsations join my intimate cycles in connection with the moon, with the poly-rhythms of my breathing together with the beating of my heart. Everything vibrates, everything drums, everything is animate. I explored the subtle singing of rhythmic sequences in nature, imagining that they could guide us into a more intimate knowledge of its vital harmony.

Et dans cette voie que j’ai commencé à dessiner.

And in this way I began to draw.

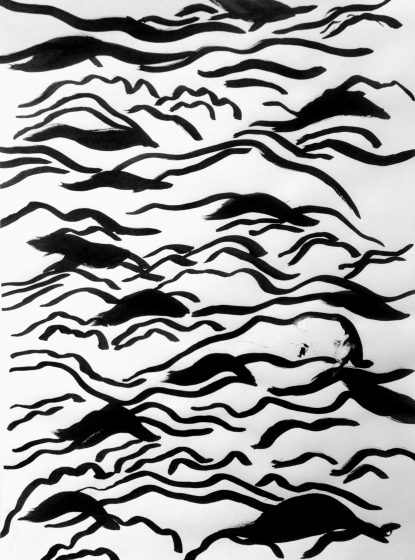

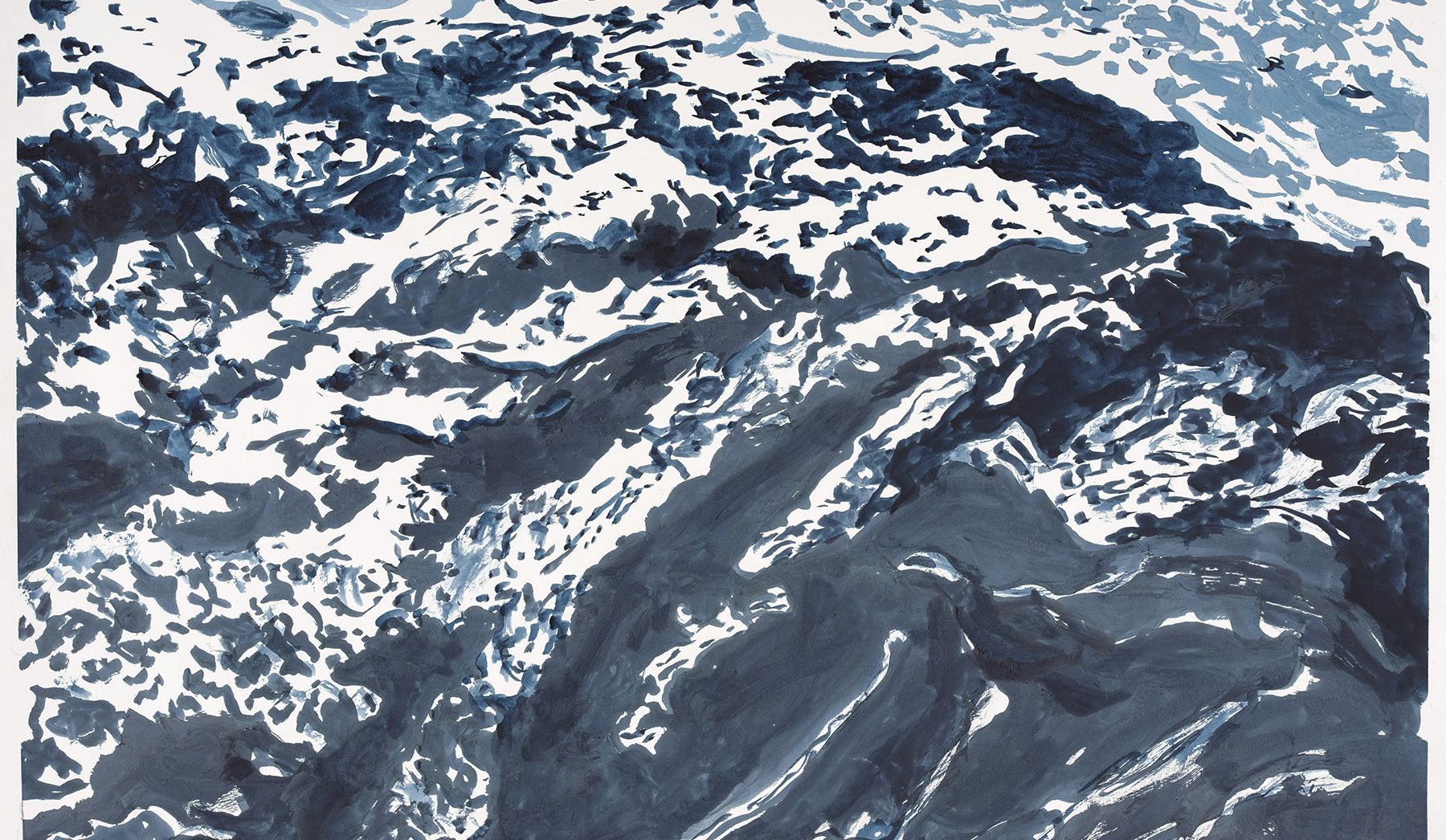

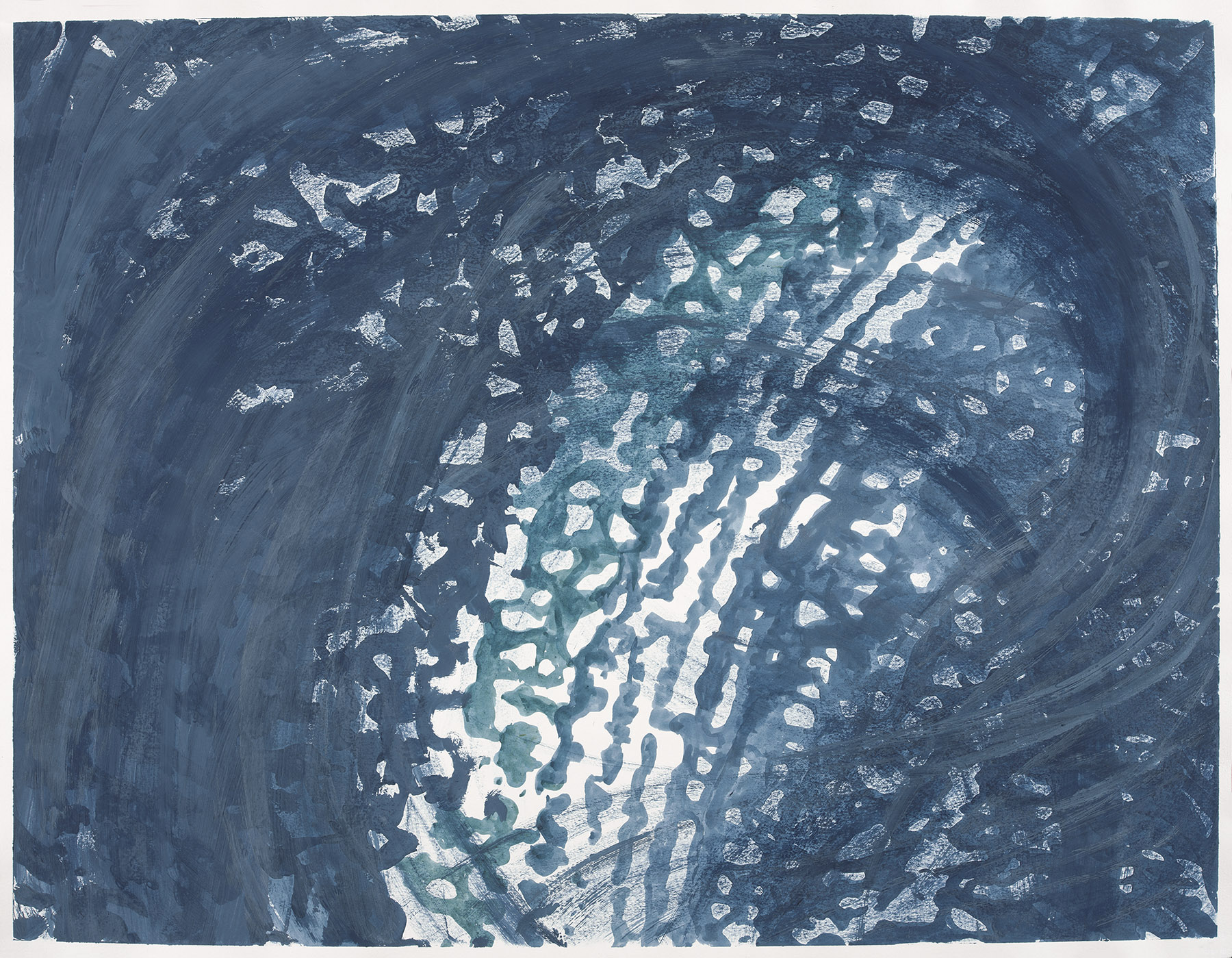

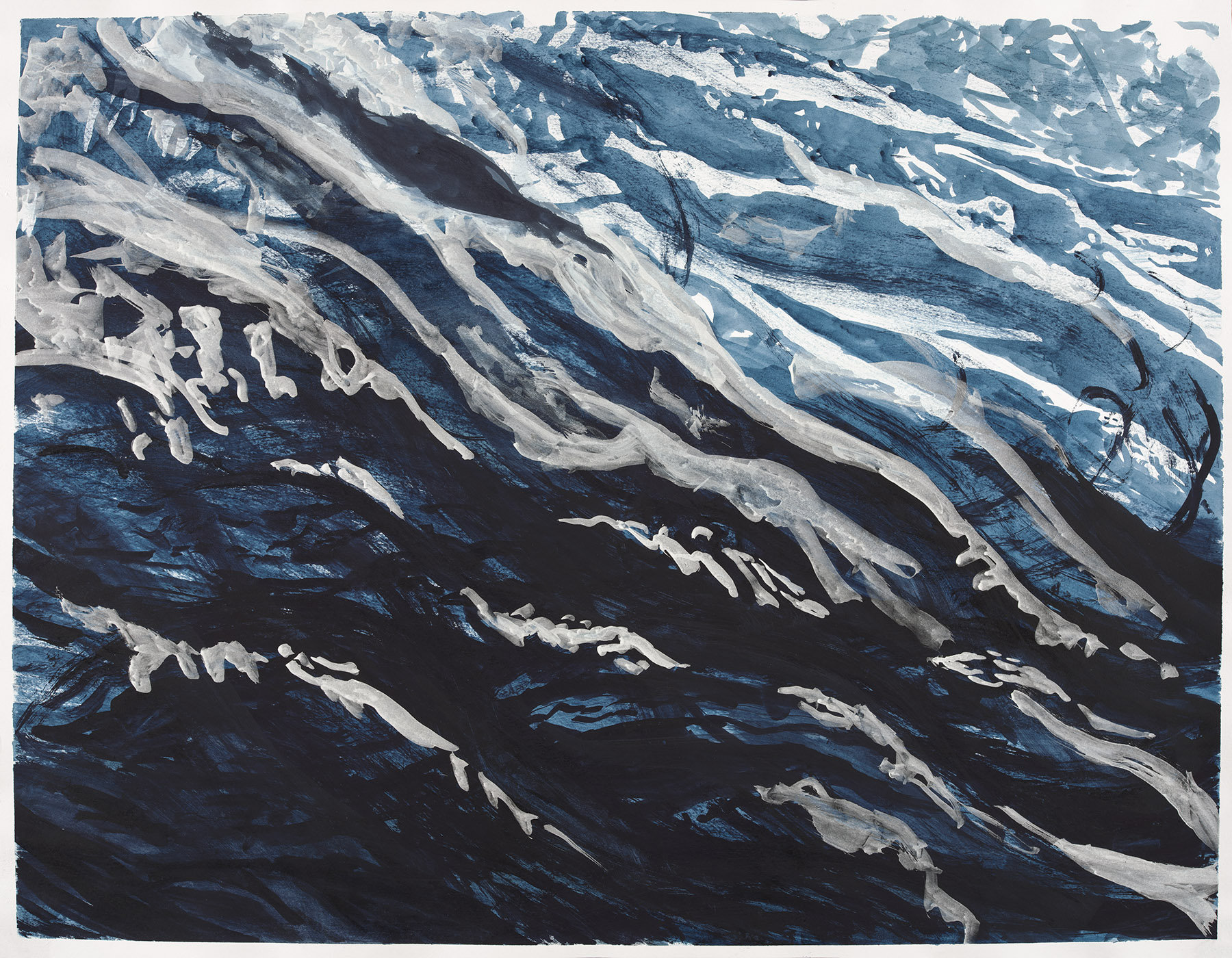

Ondulations des formes des champignons adossées aux arbres, variations de la lumière du soleil à la surface de l’eau du fleuve, le clignement récurrent de mes paupières, la danse des joncs dans le vent, les motifs réguliers sur le dos des insectes, le son régulier des vagues emportant des coquillages… Cette ébullition de formes et de sensations rythmiques m’a amené à m’intéresser aux rythmes visuels de l’écorce crevassée des arbres, particulièrement celle des vieux peupliers et des saules dont la proximité avec l’eau dilate l’écorce en motifs infinis. La vue de ces motifs m’impacte de façon profonde comme si elles harmonisaient mon rythme intérieur.

La représentation littérale de ces écorces vibrantes à la peinture bleue indigo fait rapidement émerger des images qui évoquent l’infini du sentiment océanique.

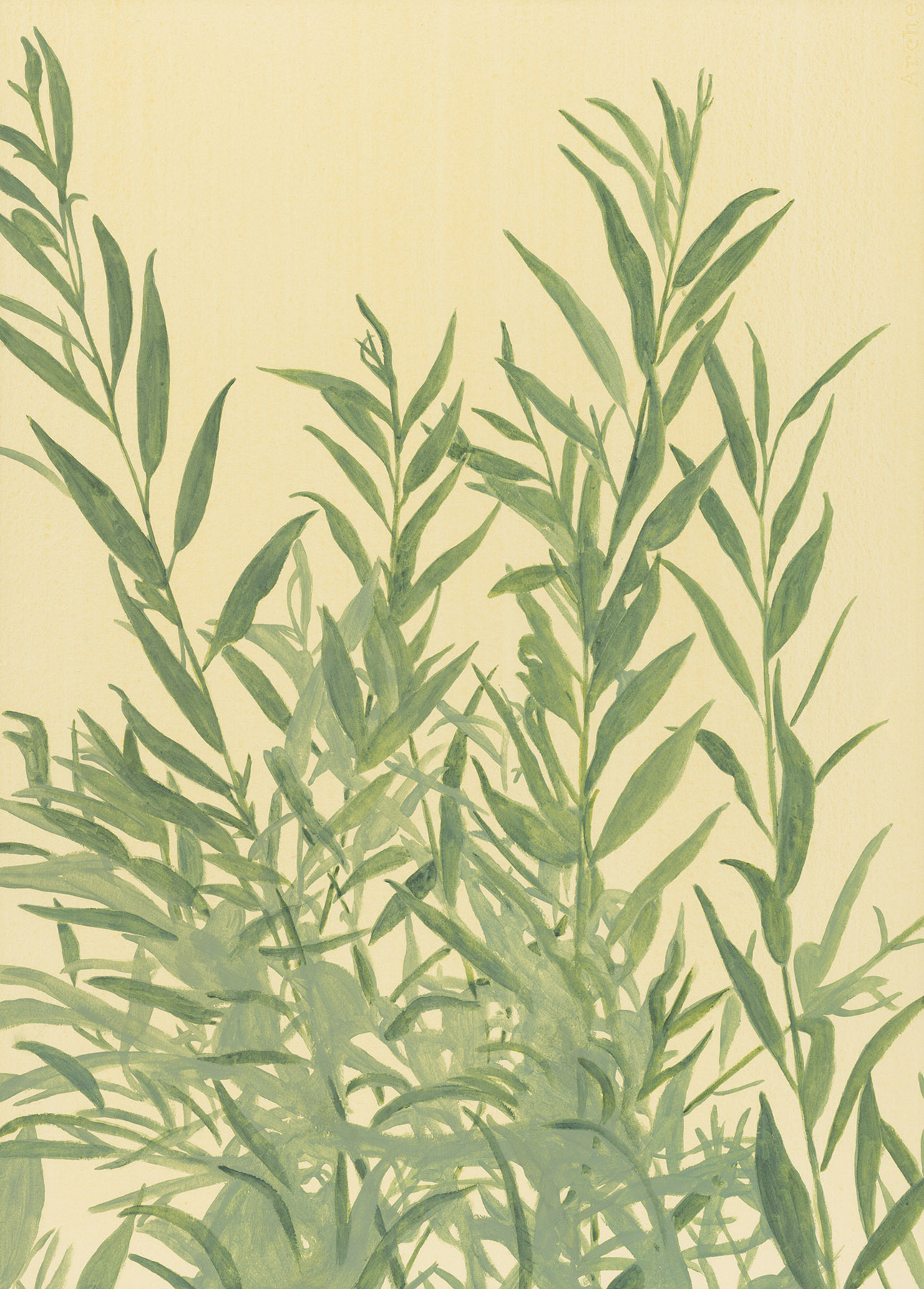

Ripples in the shapes of mushrooms leaning against trees, variations of sunlight on river water, the recurring blinking of my eyelids, the dance of rushes in the wind, the regular patterns on the backs of insects, the steady sound of waves carrying away shells… This ebullition of forms and rhythmic sensations led me to become interested in the visual rhythms of the cracked bark of trees, particularly that of the old black poplar and the willow whose proximity to the water dilates the bark into infinite patterns. The sight of these motifs has a deep impact on me, as if it harmonises my inner rhythm.

The literal representation of these vibrant barks in indigo blue paint quickly brings out images that evoke the infinity of oceanic feeling.

acte II — création

creation

pratique

UNE CÉLÉBRATION DES ARBRES

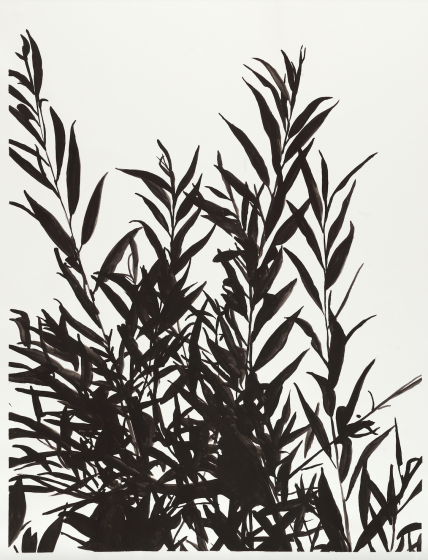

J’ai commencé à peindre avec des pigments bleu indigo qu’il me restait du Sud des Etats Unis ainsi que des pigments très colorés ramenés du Népal par ma tante et qui servent aux décors des statues sacrées et des temples miniatures. C’est l’automne et le rythme de la nature s’exprime en motifs exubérants de feuilles tombées au sol. A chaque lieu des motifs de feuilles agencées par le vent jonchant le sol raconte la diversité des arbres locaux. Au bord de la Seine, je croise les feuilles de l’aulne, du saule, du bouleau, du tilleul, du platane et dans la forêt proche se rencontrent celles du châtaignier, de l’érable, du hêtre et du chêne.

practice

A CELEBRATION OF TREES

I started to paint with indigo blue pigments that I had left from the South of the United States as well as very coloured pigments brought back from Nepal by my aunt and which are used to decorate sacred statues and miniature temples. It is autumn and the rhythm of nature is expressed in exuberant patterns of fallen leaves. In each place, the patterns of leaves arranged by the wind littering the ground tell of the diversity of local trees. On the banks of the Seine I come across the leaves of the alder, willow, birch, lime, plane tree and in the nearby forest I come across those of the chestnut, beech, maple and oak trees.

C’est cette vitalité des lieux qui m’hypnotise, et que je fais danser jusque dans mon atelier.

It is this vitality of the place that hypnotizes me, and that I make dance in my studio.

société

DE L’IMPORTANCE DE L’ESTHÉTISME

Tandis que ce processus intuitif se déroule, mon intention se définit plus clairement. J’ai passé sept années à organiser des actions concrètes pour l’environnement dans des villes françaises, américaines et turques. J’ai co-développé des services d’accès à l’alimentation locale dans des centres d’art contemporain, des ateliers de soin des écosystèmes avec des agences de paysagisme et des municipalités, ainsi que des espaces de réflexion collective. Je ressens à présent le besoin profond de raffiner une esthétique qui puisse accompagner ces actions. A la question de savoir ce qu’un artiste peut apporter en plus que les activistes et des citoyen.ne.s bénévoles qui imaginent et participent à ces engagements, j’ai compris que nous les artistes avons plusieurs rôles à jouer.

Tout d’abord, l’importance de l’esthétique, une attention apportée à la beauté et au sens. Je crois qu’il est important d’offrir des propositions qui apportent des couleurs et des formes au discours écologique. Quel que soit le médium, la pratique artistique permet de partager l’aspect émotionnel et spirituel de cette culture ancestrale du respect de la terre mère. Elle revitalise ainsi une fonction première des œuvres d’art qui est de nous connecter au reste du vivant non-humain. Elle crée des espaces pour que des formes subtiles de communication avec la nature puissent se produire. Cette fonction “magique” de l’objet artistique comme intermédiaire entre l’intérieur (la société humaine) et l’extérieur (son environnement) est au cœur de ma réflexion. Les formes esthétiques qui nourrissent notre sentiment de reliance au tout et qui perpétuent les cultures fertiles du vivre ensemble, se retrouvent communément dans les cultures autochtones et les artisanats vernaculaires du monde entier. Ils ont survécu à qui voulait les relégués au rang de simples formes décoratives. Ces objects perçus comme animés sont des hymnes profonds à la nature qui rayonne sans les mots.

society

ON THE IMPORTANCE OF AESTHETIC

As this intuitive process unfolds, my intention becomes more clearly defined. I have spent seven years organising concrete actions for the environment in French, American and Turkish cities. I have co-developed local food access services in contemporary art-centers, ecosystem care workshops with landscape agencies and municipalities and co-curated events offering shared reflection spaces. I now feel a deep need to refine an aesthetic that can accompany these actions. To the question of what an artist can bring in addition to the activists and citizen volunteers who imagine and participate in these engagements, I realized that we artists have several roles to play.

First, the importance of aesthetic, An attention to beauty and meaning. I believe it is important to offer proposals that bring colors and forms to the ecological discourse. Whatever the medium, artistic practice allows us to share the emotional and spiritual aspect of this ancestral culture of respect for Mother Earth. It revitalizes a primary function of artworks which is to connect us to the rest of the non-human living world. It creates spaces for subtle forms of communication with nature to occur. This “magical” function of the artistic object as an intermediary between the interior (human society) and the exterior (its environment) is at the heart of my reflection. Aesthetic forms that nourish our sense of connection to the whole and perpetuate the fertile cultures of living together are commonly found in indigenous cultures and vernacular crafts around the world, surviving the push to be relegated as merely decorative art forms. These objects perceived as animated are deep hymns to nature radiating without words.

développer un artisanat vernaculaire

UNE PRATIQUE ENRACINÉE DANS UN LIEU

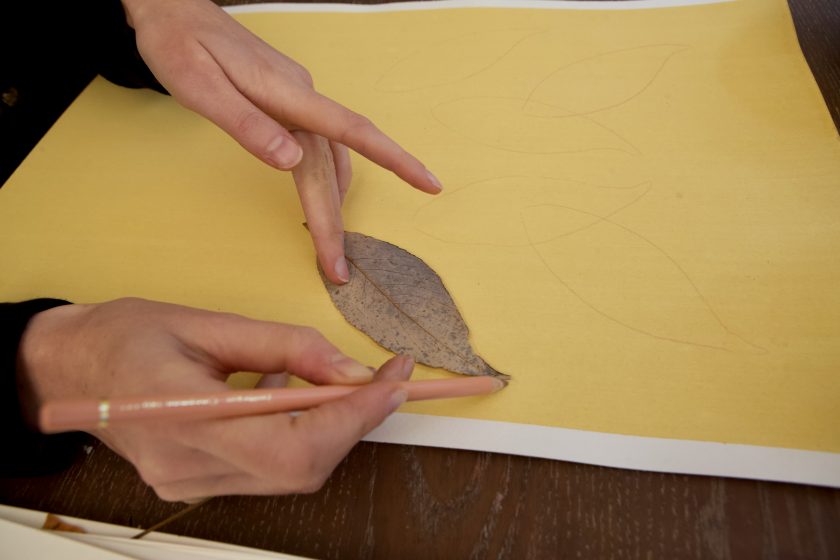

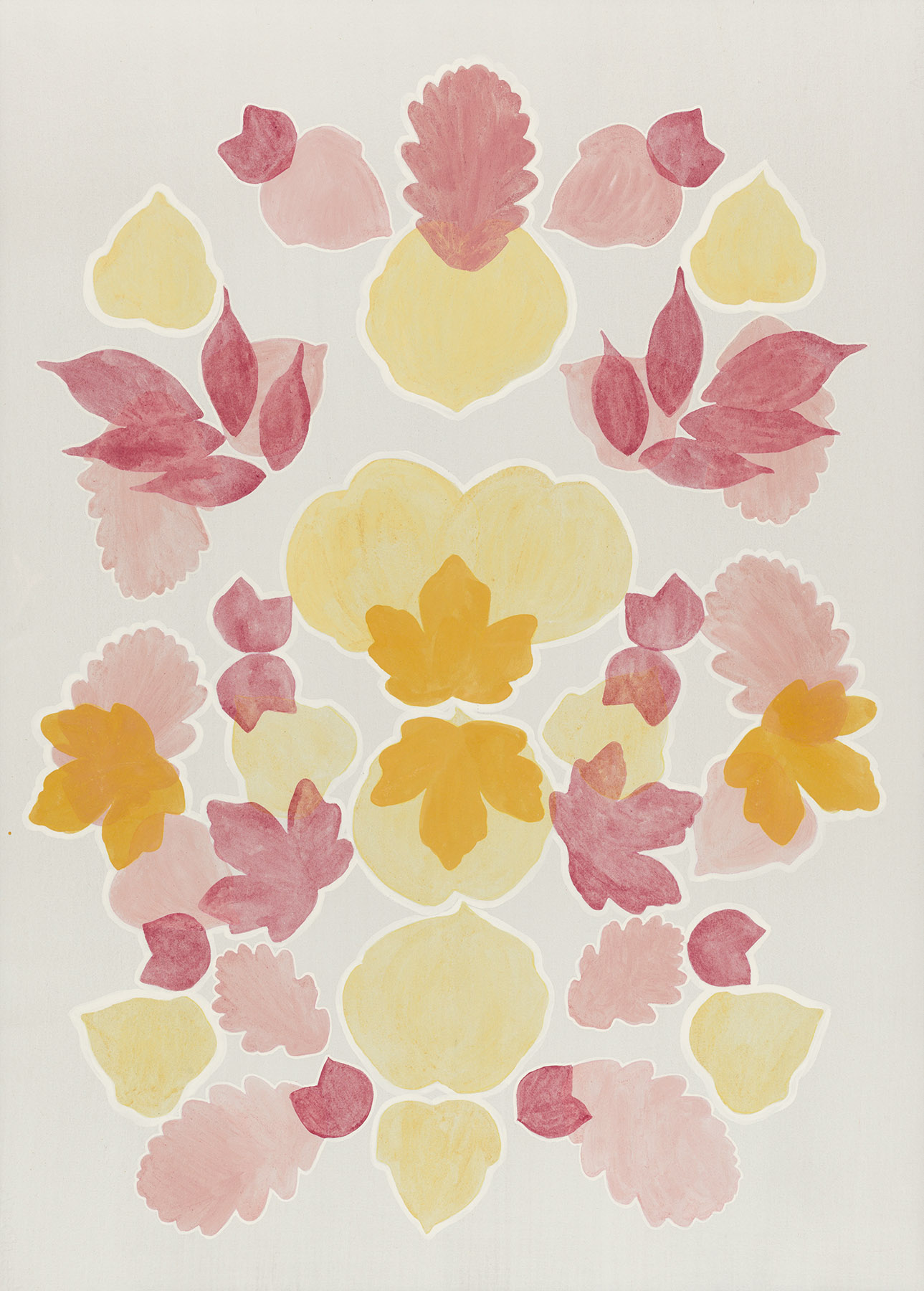

Cet idéal m’invite à m’essayer à la pratique d’un artisanat vernaculaire (propre à un pays), qui relie esthétisme et réciprocité avec le vivant non-humain. Inspirée par les motifs trouvés dans le paysage – écorces, feuilles, calligraphie de l’onde – j’ai d’abord choisi de n’inventer aucune forme et de prendre tel quel les éléments du paysage dont la physionomie m’inspire. C’est ainsi que les motifs de feuilles se sont imposés à moi avec leur anatomie particulière, chacune étant la signature de l’arbre qui les porte. Je fais sécher ces feuilles glanées lors de mes promenades dans un herbier, puis je les agence sur le papier sans réfléchir m’essayant aux résonances spontanées, créant à mon insu des compositions psychédéliques.

En parallèle, j’ai beaucoup réfléchi à la matérialité de mes travaux. Comment créer des images – ces supports d’émotions – qui soient respectueuses de la terre? En me penchant sur cette réflexion je me suis intéressé à la biodégradabilité des œuvres. Polluront-elle l’eau et les sols? J’ai vite dû abandonner la photographie et la vidéo et je suis revenue à la simplicité du papier et des pigments naturels. Se sont imposés les papiers artisanaux en coton recyclé puis en chanvre et lin, les couleurs locales faites d’argiles et de plantes spécifiques, et les liants faits d’huile et de cire. Dans cette perspective d’artisanat local j’ai recherché les couleurs les plus vives issues des espaces les plus proches de chez moi. Ce que j’ai trouvé, grâce aux fabricants de couleurs, sont des terres de Bourgogne, de Provence, du Massif Central, de l’Occitanie, d’Italie et d’Allemagne et des plantes cultivées en France, principalement dans le Sud. Cette recherche a été d’une richesse foisonnante qui m’a fait découvrir l’histoire française et européenne des couleurs. L’utilisation de ces matériaux naturels se révèle d’une grande douceur et facilité, m’offrant des moments de création exquis où les pigments ont une autonomie propre.

developing a vernacular craft

A PRACTICE ROOTED IN PLACE

This ideal invites me to try my hand at vernacular (space specific) craftsmanship, which connects aestheticism and reciprocity with non-human life forms Inspired by the patterns found in the landscape – bark, leaves, calligraphy of the wave – I chose at first to invent only I don’t use any form and take as is the elements of the landscape whose physiognomy inspires me. This is how the leaf patterns came to me with their particular anatomy, each one being the signature of the tree that bears them. I dry these leaves gleaned during my walks in a herbarium, then I arrange them on paper without thinking, trying out spontaneous resonances, intuitively creating psychedelic compositions.

In addition, I have thought a lot about the materiality of my work. How to create images – supports of emotions – that are respectful of the earth? While thinking about this, I became interested in the biodegradability of the works. Could they pollute the water and the soil? I soon had to abandon photography and video and returned to the simplicity of paper, natural pigments, with oil and wax binders. First, I used recycled cotton papers and then hemp and linen. I painted on them with local colours made from specific clay soils and plants. In this quest to produce a local craft I looked for the brightest colours from the spaces closest to home. What I found, thanks to the color makers, were soils from Burgundy, Provence, Massif Central, Occitanie, Italy and Germany and plants grown in France, mainly in the South. This research has been richly rewarding and has led me to discover French and European history of colours. The use of these natural materials turns out to be very gentle and easy, offering me exquisite moments of creation where the pigments have their own autonomy.

Petit à petit se définit un artisanat où les images sont des hymnes et des offrandes.

Little by little a craft is defined where the images are hymns and offerings.

art matriarcal

SOUTENANT LA VIE, PRATIQUE & SPIRITUEL, COMMUNAUTAIRE, EXTATIQUE

La dimension spirituelle de ce travail s’installe ainsi dans les dessins de façon intuitive. Ceux-ci deviennent support d’esprit positif, images porteuses de soin. Je m’intéresse à l’altération possible de la réalité grâce aux symboles peints qui comme des incantations magiques peuvent faire évoluer notre inconscient: des images qui font danser la joie colorée et vitale à l’intérieur de nous. En lisant les textes de Heide Göttner-Abendroth, féministe et philosophe allemande, pionnière des études comparées sur les sociétés matriarcales, j’ai réalisé que sans le savoir c’était une forme d’art et d’esthétisme matriarcale que je cherchais, à tâtons, à restaurer à travers mon travail d’artiste. Des formes esthétiques qui s’inspirent d’une force de vie presque extatique et qui souhaitent véhiculer des valeurs maternelles de soin. Mais tout d’abord, qu’est ce qu’une société matriarcale selon Heide Göttner-Abendroth?

“Les matriarcats ne sont pas simplement un renversement du patriarcat, les femmes régnant sur les hommes – comme le veut l’interprétation erronée habituelle. Les matriarchies sont des sociétés centrées sur la mère, elles sont basées sur les valeurs maternelles : prendre soin, nourrir, être maternel, assurer la paix, ce qui vaut pour tout le monde : pour les mères et celles qui ne le sont pas, pour les femmes et les hommes. Les sociétés matriarcales sont consciemment construites sur ces valeurs maternelles et le travail maternel, et c’est pourquoi elles sont beaucoup plus réalistes que les patriarcats. Elles sont, par principe, axées sur les besoins. Leurs préceptes visent à satisfaire les besoins de chacun avec le plus grand bénéfice. Ainsi, dans les matriarcats, le maternage – qui a pour origine un fait biologique – se transforme en modèle culturel. Ce modèle est beaucoup plus approprié à la condition humaine que la façon dont le patriarcat a conceptualisé la maternité et l’a utilisée pour faire des femmes, et en particulier des mères, des esclaves.(…) Les matriarchies sont des sociétés où l’égalité est complémentaire et où l’on prend grand soin d’assurer un équilibre. Cela s’applique à l’équilibre entre les sexes, entre les générations, et entre les humains et la nature.”

De toutes les régions du monde, l’Europe est la seule où les sociétés matriarcales ont complètement disparues. De la même façon, les formes artistiques qui portent ces valeurs se sont elles aussi progressivement éteintes. Les formes d’art matriarcal ne sont pas basés sur la fiction, ils interviennent sur le réel à travers des symboles dynamiques. De cette façon, cet forme d’art n’est pas figée ou inerte mais est un processus où chacun.e participe à la manifestation des symboles (issus d’une mythologie matriarchal connue de tous) dans la matérialité d’un quotidien partagé. L’on peut imaginer aujourd’hui que cette mythologie connue de tous soit celle de la terre mère telle qu’elle se présente sous son jour à la fois scientifique et spirituel (l’art matriarcal ne faisant pas de distinction entre les deux). En combinant la contemplation, l’identification à et l’action structurés par une série de symboles à la fois concrets et mythiques, cet art peut amener à des états d’être, parfois extatiques, qui ont le pouvoir de faire changer la réalité individuelle et collective.

“Le système de valeurs matriarcal est entièrement différent du système patriarcal (…) L’érotisme est son pouvoir dominant – pas le travail, la discipline ou le renoncement. La perpétuation de la vie comme un cycle de renaissances est son principe le plus élevé.”

Aujourd’hui de plus en plus d’artistes contemporaines font revivre ces fonctions d’un art non séparé de la vie, un art spirituel et social, non hiérarchique, public, relationnel et de transformation. Porté par un sens du soin et de la communauté, il se dédit au soutien du bien vivre de tous en mêlant pratiques symboliques et actions concrètes de terrain.

matriarcal art

LIFE-AFFIRMING, PRACTICAL & SPIRITUAL, COMMUNAL, ECSTATIC

The spiritual dimension of this work then settles in the drawings in an intuitive way. They become a support for positive spirit, images that carry care. I am interested in the potential alteration of reality through painted symbols which, like magical charms, can evolve our unconscious: images that make the colourful and vital joy dance within us. While reading the texts of Heide Göttner-Abendroth, German feminist and philosopher, pioneer of comparative studies on matriarchal societies, I realised that without knowing it, it was a form of matriarchal art and aesthetics that I was trying to restore in my artistic works. Aesthetic forms that are inspired by an almost ecstatic life force and that wish to convey maternal values of care. But first, what is a matriarchal society for Heide Göttner-Abendroth?

“Matriarchies are not just a reversal of patriarchy, with women ruling over men – as the usual misinterpretation would have it. Matriarchies are mother-centered societies, they are based on maternal values: care-taking, nurturing, motherliness, peace building which holds for everybody: for mothers and those who are not mothers, for women and men alike. They are consciously built upon these maternal values and motherly work, and this is why they are much more realistic than patriarchies. They are, on principle, need-oriented. Their precepts aim to meet everyone’s needs with the greatest benefit. So, in matriarchies, mothering – which originates as a biological fact – is transformed into a cultural model. This model is much more appropriate to the human condition than the way patriarchy has conceptualised motherhood and used it to make women especially mothers into slaves.(…) Matriarchies are societies with complementary equality, with great care is taken to provide a balance. This applies to the balance between genders, among generations, and between humans and nature.”

Of all the regions of the world, Europe is the only one where matriarchal societies have completely disappeared. In the same way, the artistic forms that carry these values have also gradually disappeared. Matriarchal art forms are not based on fiction, they intervene on reality through dynamic symbols. In this way, this art form is not fixed or inert but is a process where everyone participates in the manifestation of symbols (from a matriarchal mythology known to all) in the materiality of a shared daily life. One can imagine today that this mythology known to all is that of the mother earth such as it is presented under its day at the same time scientific and spiritual (the matriarchal art not making distinction between the two). By combining contemplation, identification with and action, structured by a series of symbols both concrete and mythical, this art can lead to states of being, sometimes ecstatic, that have the power to change individual and collective reality.

“The Matriarchal system of values is entirely different from the patriarcal one (…) Eroticism is its dominant power — not work, discipline, or renunciation. The perpetuation of life as a cycle of rebirths is it’s highest principle.”

Today, more and more contemporary artists are reviving these functions of an art that is not separated from life, a spiritual and social art, non-hierachical, public, relational and transformational. Carried by a sense of care and community, it is dedicated to supporting the good life of all by mixing symbolic practices and concrete actions in the field.

acte III — passerelle vers la ville

gateway to the city

entrer à nouveau dans Paris

APRES DEUX ANNEES DE VIE A LA CAMPAGNE

J’ai décidé de me ré-enraciner dans Paris, là où je suis née. De la forêt large à la forêt urbaine. Le hasard m’a ramené au point de départ, dans le quartier de mon enfance, au pied de la butte Montmartre. J’amène beaucoup de choses dans mes bagages. La perspective du temps long que je peux appliquer à la ville, regarder sa géographie, sa géologie, sa topographie, ses rivières et canaux, ses monts et ses parcelles de forêt. Le ressenti intuitif en milieu urbain, le lien avec les jardiniers de la ville, avec les arbres, avec les squares, avec les jeunes plantes qui reverdissent ma rue. C’est ma féminité intuitive qui se déploie parmi les bâtiments. Je recherche les espaces de connexion avec la nature urbaine non-humaine, dans les rares parcs et au bord de la Seine.

En fin de semaine aussi je partais à vélo à la recherche d’autres espaces verts à la périphérie de la ville qui puissent eux aussi me connecter au temps lointain, comme le fait la forêt de Fontainebleau. J’ai ainsi exploré la forêt de Rambouillet et les rives de la Marne, espaces régénérants à porter de ville.

to enter Paris again

AFTER TWO YEARS OF LIVING IN THE COUNTRYSIDE

I finally decided to put down roots in Paris, where I was born. From the wide forest to the urban forest. Chance brought me back to the starting point, in the neighborhood of my childhood, at the foot of the Butte Montmartre. I bring many things in my luggage. The perspective of a deep time that I can apply to the city, to look at its geography, its geology, its topography, its rivers and canals, its mountains and its patches of forest. The intuitive feeling in the urban environment, the link with the gardeners of the city, with the trees, with the squares, with the young plants that green my street. It is my intuitive femininity that unfolds among the buildings. I look for spaces of connection with the non-human urban nature, in the rare parks and at the edge of the Seine.

At the end of the week, I also went by bike in search of other green spaces on the outskirts of the city that could also connect me to the distant past, as the forest of Fontainebleau does. I thus explored the forest of Rambouillet and the banks of the Marne, regenerating spaces close to the city.

célébrer la forêt urbaine

PASSER LES FRONTIERES ENTRE EXTERIEUR ET INTERIEUR DE LA VILLE

Le fait de connaitre intimement les forêts qui jouxtent Paris, m’aide énormément à ressentir l’unité de la forêt urbaine et sa présence quotidienne. Comme une entité géante qui n’a que faire des frontières entre ville, banlieue et campagne, enjambant les boulevards périphériques à coup de spores volants, de corridors verts et de graines transportées par les oiseaux.

Un jour, alors que je médite sous l’un des platanes d’Orient oles plus vieux de mon quartier parisien – planté en 1872 au square Montholon – et que je partage en pensée avec l’arbre mon manque de nature, je vois arriver de nulle part une petite camionnette de jardin remplie de jeunes arbres à planter. Ni une ni deux, remplie d’émotion face à cette réponse si belle, je demande aux jardiniers si je peux les aider à planter ces jeunes pousses. Le plus âgé d’entre eux m’a tout de suite rétorqué que c’était impossible en raison des assurances. Mais le plus jeune d’entre eux, surpris et heureux de trouver une comparte, à rétorquer que je serais sa stagiaire pour la plantation! Et c’est ainsi que grâce à Sophoan et au vieux platane, j’ai pu m’ancrer dans la nature de ma ville en plantant une vingtaine de jeunes arbres. Geste que j’avais pu faire à la campagne mais rarement en ville.

Cela m’a rappeler des démarches de jardinage participatif que j’avais eu la chance d’expérimenter à New York, à travers le Super Steward Program, une initiative de la ville qui invite chacun.e grâce à de très courtes formations à travailler au soin de la nature urbaine. Identification des espèces, élagage des arbres, plantation des pieds d’arbres, action de nettoyage, d’arrosage, etc. tout un panel d’action possibles pour créer une relation de “care” avec les arbres de son quartier. A Paris, l’initiative Végétalisons Paris, lancée par la Mairie, permet à tout citoyen majeur de jardiner dans la rue via un permis de végétaliser. Une façon aussi de se rapprocher des arbres.

celebrating the urban forest

CROSSING THE BORDERS BETWEEN OUTSIDE AND INSIDE THE CITY

The fact that I know intimately the forests that border Paris, helps me enormously to feel the unity of the urban forest and its daily presence. Like a giant entity that doesn’t care about the borders between city, suburb and countryside, spanning the city’s ring roads with flying spores, green corridors and seeds carried by birds.

One day, as I meditate under one of the oldest Oriental plane trees in my Parisian neighbourhood — planted in 1872 in the Montholon garden- and as I share in thought with the tree my lack of nature, I see a small garden van arrive from nowhere, filled with young trees to be planted. Filled with emotion at this beautiful response, I asked the gardeners if I could help them plant the saplings. The oldest of them immediately retorted that it was impossible because of insurances. But the youngest of them, surprised and happy to find a counterpart, retorted that I would be his trainee for the planting! And so, thanks to Sophoan and the old plane tree, I was able to anchor myself in the nature of my city by planting about twenty young trees. A gesture that I had been able to do in the country but rarely in the city.

This reminded me of the participatory gardening approach I had had the chance to experience in New York, through the Super Steward Program, a city initiative that invites everyone, thanks to very short training sessions, to work on the care of urban nature. Identification of species, pruning of trees, planting at the foot of trees, cleaning, watering, etc. a whole range of possible actions to create a relationship of “care” with the trees in one’s neighborhood. In Paris, the “Végétalisons Paris” initiative, launched by the City Council, allows any citizen of legal age to garden in the street via a vegetation permit. This is also a way to get closer to the trees.

Je continue mes promenades quotidiennes, comme si j’étais en forêt, à observer les arbres urbains et à essayer de deviner leur nom et leur ressenti.

I continue my daily walks, as if I were in the forest, observing the urban trees and trying to guess their names and feelings.

l’atelier en ville

Rapidement, j’installe un atelier chez moi. Peint toute en blanc, j’y accueille toutes les feuilles, branchages, pierres et autres éléments glanés dans les rues et les squares, au milieu des pigments et des papiers. Je collecte les feuilles d’arbres de ma rue, et mon travail hypnotique se manifeste en de nouvelles compositions. Je fête ma rue venant tout juste d’être végétalisée, comme beaucoup d’espaces du quartier, témoin du verdissement progressif d’un des quartier les moins vert de la capitale.

Au même moment, une jeune galerie L’Atelier Bergère ouvre dans ma rue, où j’expose mon travail in situ, ainsi qu’à la Galerie Marie-Robin dans le quartier du marais non loin de là. Je commence à être invitée à participer à des expositions d’art dans une optique participative. Il est temps pour moi de faire parler l’influence de l’”art matriarcal” en créant des œuvres d’art qui mêlent une esthétique forte symbolisant la flore locale à des questions en lien avec les problématiques de la vie réelle.

the workshop in the city

I quickly set up a workshop space at home. Painted all in white, I welcome all the leaves, branches, stones and other gleaned elements from the streets and gardens, in the middle of pigments and papers. I collect the leaves of the trees on my street, and my hypnotic work manifests itself in new compositions. I celebrate my street having just been greened, like many spaces in the neighborhood, witnessing the progressive greening of one of the least green neighborhoods in the capital.

At the same time, a young gallery L’Atelier Bergère opens in my street, where I exhibit my work in situ, as well as at the Galerie Marie-Robin in the nearby Marais district. I start to get invited to do art shows with a participatory lens, time for me to get the “matriarcal art” influence speak by making art pieces that mixes a strong aesthetic symbolising the local flora with real life issues.

L’atelier devient une petite fabrique urbaine, où se mêle matériaux et feuilles d’arbres des villes en attente de s’intégrer à des actions de soin de la nature: sous formes d’images, de costumes, de drapeaux.

The workshop becomes a small urban factory, where materials and leaves from city trees are mixed together, waiting to be integrated into actions to care for nature: in the form of images, costumes, flags.

acte IV — actions directes

direct actions

LE “CARE” EN ACTION

DES IMAGINAIRES EN PRATIQUE

Ce langage esthétique et cette technique simple d’éco conception d’image dont je viens de vous conter l’émergence, je souhaite à présent les mettre au service d’actions locales communautaires en faveur de l’environnement. A l’image de ce que j’ai pu développer depuis une dizaine d’année principalement à l’étranger, je commence à collaborer en Europe et en France avec des organismes publics ou privés qui entretiennent les espaces verts (municipalité, entreprise, association, etc), ainsi que des lieux de diffusion de la culture ayant une ligne environnementale (musée, centre d’art, galerie, etc) en apportant des supports visuels riches d’un vocabulaire situé.

Pour des centres d’art contemporain comme le Palais de Tokyo à Paris et Pioneer Works à New York j’avais déjà pu co-créer des espaces de rencontres entre activisme écologique et pratiques artistiques: avec la distribution de fruits, herbes et légumes locaux dans ces lieux avec l’artiste Geoffroy Pithon, l’organisation de repas partagés bio & local, de marches artistiques avec la cheffe Anne Apparu Hall et la ferme Red Hook community, ou d’actions soin des écosystèmes adjacents au musée. Ici quelques images d’une performance participative de restoration des écosystèmes de bords de de berges à Red Hook, Brooklyn. Une collaboration avec le Greenbelt Native Plant Center-NYC Parks qui nous à fourni des plantes endémiques à l’estuaire de l’Hudson. Mais le besoin d’un apport artistique plus fort dans ces projets militants était toujours présent.

CARING IN ACTION

IMAGINARIES IN PRACTICE

This aesthetic language and simple technique of eco-conception of image which I have just told you about, I wish now to put at the service of local community actions in favour of the environment. Like what I have been able to develop for the last ten years mostly abroad, I wish to partner with public or private organisations here in Europe and France that maintain green spaces (municipality, company, association, etc.), as well as places of diffusion of the culture having an environmental line (museum, art center, gallery, etc.) by bringing coherent visuals connected to a local vocabulary.

For the contemporary art-centers of the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and Pioneer Works in New York, I was already able to co-create spaces for encounters between ecological activism and artistic practices: distributing local fruits, veggies and herbs in such places with the artist Geoffroy Pithon, organising organic & local community meals with the cheffe Anne Apparu Hall and Red Hook community farm, artistic walks, or actions of wild plantations next to the museum. Here some images of a participative performance of restoration of the ecosystems of edges of banks in Red Hook, Brooklyn. A collaboration with the Greenbelt Native Plant Center-NYC Parks which provided us with plants endemic to the Hudson estuary. But the need for stronger artistic input into those activist project was still there.

Comment croiser véritablement actions locales communautaires en faveur de l’environnement et une esthétique artistique?

How to truly combine local community actions in favour of the environment with an artistic aesthetic?

Voilà quelques exemples des travaux où j’ai tenté de combiner actions concrètes et images situées et éco-conçues. Cela a été le cas lorsque j’ai réalisé des drapeaux en teinture indigo et aux motifs inspirés de la faune et de la flore locale, pour les jardins communautaires des Far Rockaways dans le Queens à New York par exemple. Les drapeaux ont été réalisés sur coton bio en utilisant de la cire d’abeille du Queens pour faire les reserves blanches ensuite teinte à l’indigo du Sud des Etats Unis. Les motifs choisis étaient ceux des joncs de la baie, des élégantes solidages, des traces laissées par les limules sur la plage lors de leur saison des amours, les formes des oiseaux migrateurs, et plus encore. Ces travaux s’inscrivaient dans la restauration de ces jardins potagers suite au terrible ouragan Sandy qui a dévasté ce quartier. Un projet porté par l’agence de paysagisme Till Design pour laquelle j’ai travaillé avec Victoria Marshall et Renae Reynolds et la New York City Urban Field Station intitulé Landscape of Resilience qui ensemble ont participé à restorer des espaces de jardins qui puissent résister au mieux aux futures ouragans dû au changement climatique.

Here are few examples of my past work where I tried to combine concrete actions and eco-designed and space-specific images. This was the case when I made flags in indigo dye and patterns inspired by local flora and fauna, for the Far Rockaways community gardens in Queens, New York for example. The flags were made on organic cotton using Queens beeswax to make the white reserves and then dyed with Southern US indigo. Patterns chosen were those of the bay’s rushes, the elegant golden rod, the tracks left by horseshoe crabs on the beach during their mating season, the shapes of migratory birds, and more. These works were a small part of the restoration of these vegetable gardens following the terrible Hurricane Sandy that devastated the neighbourhood. A project of the landscape design agency Till Design for which I worked with Victoria Marshall and Renae Reynolds and the New York City Urban Field Station, untitled Landscape of Resilience who together participated in restoring garden spaces that can best withstand future hurricanes due to climate change.

Aussi, rentrant en Europe, j’ai été invitée par l’artiste et ami Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro à imaginer ensemble une performance pour le ZKM museum à Karlsruhe, dans le cadre de l’exposition Critical Zones – Observatories for Earthly Politics commissionnée par Bruno Latour, Peter Weibel, Martin Guinard et Bettina Korintenberg. Il était question de relier le musée à un verger voisin abandonné en vue d’en prendre soin sur le long terme. Pour cette performance nous avons imaginé des vêtements, écharpes en tissu brut peint avec du brou de noix et des réserves à la cire. Les formes peintes étaient inspirées des formes des branches des arbres du vergers, principalement des pommiers, poiriers et cerisiers. La performance de “reliance” prit la forme d’une marche entre les deux espaces – musée et verger – parée des formes des arbres. Celle-ci fut introduite par une méditation et ponctuée de lecture de textes. Sur place nous avons procédé à l’élagage des arbres fruitiers avec deux agents des espaces verts de la ville venus nous former. Les formes peintes sur tissu ont accompagnées ce rituel de soin, et chacun à pu les garder comme trace de ce moment et costume pour les futures actions dans le verger.

Also, when coming back to Europe, I was invited by the artist and friend Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro to imagine together a performance for the ZKM museum in Karlsruhe, in the context of the exhibition Critical Zones – Observatories for Earthly Politics commissioned by Bruno Latour, Peter Weibel, Martin Guinard and Bettina Korintenberg. The idea was to connect the museum to a nearby abandoned orchard in order to take care of it long term. For this performance we imagined clothes, scarves in raw fabric painted with walnut stain using wax reserves. The painted forms were inspired by the forms of the branches of the trees of the orchard, mainly apple trees, pear trees and cherry trees. The performance of “connection” took the form of a walk between the two spaces – museum and orchard – adorned by the motifs of the trees. The walk was introduced by meditation and punctuated by readings. On site we proceeded to the pruning of the fruit trees with two agents of the green spaces of the city who came to train us. The shapes painted on fabric accompanied this ritual of care, and everyone could keep them as a trace of this moment and costume for future actions in the orchard.

Cette expérience a été suivie d’un autre projet artistique dans un verger, plus récemment en Bourgogne, en France, à l’invitation d’une association environnementale locale. Cette association, appelée le Ruban Vert, s’investit dans le renforcement d’un corridor vert pour la biodiversité locale le long duquel elle maintient de nombreux points d’accès à l’eau. Lorsqu’ils m’ont contacté pour participer à leur premier festival de Land Art, j’ai proposé que nous créions ensemble une nouvelle mare dans le cadre de mon intervention artistique. Cette petit mare a été créé au centre d’un ancien verger. La région étant réputée pour la qualité de son argile depuis des siècles, nous en avons tapisser le sol pour l’imperméabiliser. En fait, de nombreuses mares de la région étaient enfaite d’anciens trous d’extraction pour les usines de briques ou de tuiles. L’installation artistique se composait également de bancs peints et d’éléments en bois, terre cuite et émaux de la région (terre de Puisaye et Treigny). Ces trois bancs en céramique sont des “tableaux” peints avec des motifs de différents saules, accompagnés de six petits éléments en céramique qui servent de “pierres” artificielles sur le côté de l’étang pour que les grenouilles et les insectes puissent s’y reposer.

This experience was followed by another art project in an orchard, more recently in Burgundy, France, at the invitation of a local environmental association. This association, called le Ruban Vert, literally “the green ruban”, is committed to strengthening a green corridor for local biodiversity along which it maintains numerous water access points. When they reached out to me to participate in their first Land Art festival, I proposed that we create together a new pond as part of my artistic intervention. This little pond was created in the centre of an old orchard. The region being famous for its clay quality since centuries we used it to imperialise the soil. In fact many actual ponds in the region were former extraction holes for brick or tiles factories. The installation was also composed of painted benches and elements made of wood, terracotta and enamels from the region (earth from Puisaye and Treigny). The three ceramic benches are like “paintings” painted with motifs of various willow trees, accompanied by six small ceramic elements to serve as artificial “stones” on the side of the pond for frogs and insects to rest on.

Alors j’ai de plus en plus d’occasions de travailler dans le domaine de l’art écologique, je souhaite continuer à imaginer des expériences poétiques et pratiques qui trouvent leur beauté dans la satisfaction simultanée des besoins humains et non-humains. Cette recherche se fait à tâtons, très progressivement, guidée par le sentiment profond qu’il s’agit d’essayer de réconcilier des images émanant de l’environnement directe et pratiques qui l’honore.

Merci d’avoir plongé dans cette recherche ici avec moi et à celles et ceux qui ont rendu cette publication possible. Je serais ravie de découvrir vos points de vue sur ces sujets dans la section dédié à la discussion ci-dessous. Vous pourrez aussi suivre mon travail via mon site internet.

Au plaisir d’échanger avec vous!

As I get more opportunities to work in the ecological art field, I wish to continue to imagine poetical and practical experiences that find beauty in meeting both human and non-human needs. This research is done by trial and error, very gradually, guided by the deep feeling that it is a question of trying to reconcile images emanating from the direct environment and practices that honour it.

Thank you for diving into this research here with me, and thanks to those who made this publication possible. I would be thrilled to read about your view points on the themes we talked about bellow in the open discussion section. You can also follow my work via my website.

I am looking forward to talking with you!

DISCUSSION OUVERTE

Comment les arts peuvent contribuer de façon concrète à la transition écologique?

OPEN DISCUSSION

How can the arts contribute in a concrete way to the ecological transition?

Takamatsu Iki

Korea

Thank you for this work. You premise this exhibition on the RWK quote about knowledge being resident in the land. Like so many urbanites, I could not fathom this years ago. Of course I could not. Cities seem to have so little ‘nature’ where we can look to for knowledge. However, through your story and work, you remind us that this nature (and these answers) are indeed all around us. I agree that the most deeply moving and impressive art comes in various ways from this ‘nature knowledge’. Art of this caliber reminds us that perhaps we already have all the answers, we just need to look deeper, slower, and linger a bit longer to find them. Now I am wishing to visit Fontainebleau again! Thank you for your beautiful work.

Eloi

France

Les arts n’installent pas d’usines à énergie renouvelable

Mais donnent de l’énergie renouvelable

C’est un dessin, une vidéo, un poème

Qui rappelle que l’on est plus qu’une réussite personnelle

Que l’on est vulnérable

Que ta voisine l’est aussi

Que ton humanité frémit

Et que la forêt, elle aussi

Et tout ça injecte en toi

Le sentiment du Vivant

Et que ce Vivant vive sans que j’arrive à le croire

Cela peut durer longtemps

Jusqu’à ce moment

Où trois mots d’un.e poète me font sentir vivant

À l’intérieur de plus Grand

Et là… seulement

S’installe en moi l’énergie renouvelable de l’agir.

Response 3

Country

Coming soon. Respond above.

Production

The Forum for Radical Imagination on Environmental Cultures (FRIEC) at The Nature of Cities.

Carmen Bouyer, artist

Karen Tsugawa, TNOC web developer

support:

David Maddox, TNOC director

Patrick M. Lydon, TNOC arts editor

credits:

All images (drawings and photographs) are by Carmen Bouyer, unless stated otherwise.