ESSAYS | POINTS OF VIEW

-

The Additional Role of the Urban Beaches in the Face of Climate Change

Sun, sand, and sea tourism is one of the most popular and widespread types of tourism worldwide. It originated in the healing practices of the 19th century when…

-

Recognizing Rights and Responsibilities for Plants in the Metropolis

The Landscape Lab, on the campus of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, is a stormwater management landscape designed that serves as stormwater infrastructure but also…

-

Seeing Biocultural Mosaics: The Stewardship Salon Approach

It can be easy to remain in the bubble of your own perspective, thinking that one’s relationship to place might be a universal phenomenon. When the phenomenon, in…

TNOC’S MISSION

Cities and communities that are better for nature and all people, through transdisciplinary dialogue and collaboration.

We combine art, science, and practice in innovative and publicly available engagements for knowledge-driven, imaginative, and just green city making.

ROUNDTABLES | GLOBAL DISCUSSIONS

MORE VIEWS | FROM THE ARCHIVE

SUPPORT BETTER CITIES,

JOIN OUR NETWORK OF DONORS…

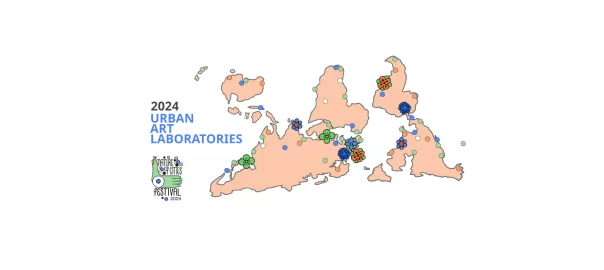

PROJECTS | ART, SCIENCE & ACTION, TOGETHER

NBS COMICS: NATURE TO SAVE THE WORLD

26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity

Now a global project with over ONE MILLION readers, we invite comic creators from all over the world to combine science and storytelling with nature-based solutions (NBS).

JOIN THOUSANDS OF READERS

AROUND THE WORLD…

MORE TNOC PROJECTS | ART, SCIENCE & SOCIAL JUSTICE

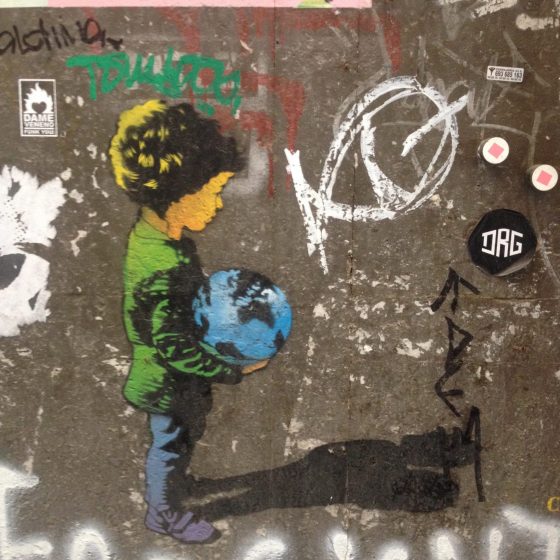

THE NATURE OF GRAFFITI

This is the nature of graffiti. It facilitates speech. It speaks to us. It stakes claims and makes statements. It tells stories.

The Nature of Cities hosts a public gallery about the graffiti and street art that motivates us in public places.

REVERBERATIONS EXHIBITION

Close your eyes. What do you hear?

An exhibition exploring the elements through art, science, and sound, with over 30 contributors from various disciplines in a multimedia experience. Produced by the USDA Forest Service and The Nature of Cities.

THE JUST CITY ESSAYS

26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity

Produced by The Nature of Cities, together with The J. Max Bond Center, and Next City, we ask what would a just city look like, and what could be strategies to get there? We raised these questions to architects, mayors, artists, doctors, designers, scholars, philanthropists, ecologists, urban planners, and community activists. Their responses came to us from 22 cities across five continents and myriad vantages.