For the first time in our history, more people live in urban vs. rural areas and humans continue to move into cities. Cities have huge impacts on our natural resources. Urban dwellers consume vast amounts of energy, produce waste, and alter landscapes to the point where native plant and animal populations decline precipitously. As cities grow, people have pondered – can we develop land without destroying our natural heritage?

While conventional development has years of inertia behind it, there is a movement afoot to design and manage growing cities in a more sustainable fashion. You most likely have heard the buzzwords – green development, new urbanism, smart growth, conservation development, etc. Urban communities have and will continue to expand, and the aforementioned concepts attempt to reduce our collective impact on local and surrounding environments.

Why are green developments different? The goals are conservation while providing a unique living experience, which includes energy efficiency, alternative transportation, livability and walkability, and water conservation. Biodiversity, however, often is lower on the totem pole of priorities and is not explicitly addressed in urban development plans, unless an endangered species is identified. And even then, it may not be addressed adequately.

Biodiversity, which refers to variety of life and its processes, is unique to each region and country. Metropolitan areas are embedded in natural systems, and the urban matrix dissects and sometimes surrounds natural areas. Often the end result is the homogenization of species within cities. As one travels from one city to the next, exotic species dominate; from turfgrass to ornamentals, it is often difficult to distinguish one city from another. Further, cities impact natural habitats near and far away. For example, both animal and plant invasive exotics can overrun natural environments, and theses invasives (e.g., Burmese pythons and Chinese tallow trees) often originate from peoples’ yards.

As an urban wildlife ecologist, I have been involved with a number of green development projects, not only conducting research but also implementing outreach programs and consulting with planners, developers, and citizens. Often, there are many connections between biodiversity conservation and energy, water conservation, transportation, and walkability strategies. Examples include conserving native trees near buildings (which provide shade to reduce energy consumption during the summer) and clustering homes to reduce vehicle miles traveled (which conserves open space for wildlife habitat). From my experiences, though, many green development projects fail to meet the test of time and the original intent is lost, and the community becomes dysfunctional, at least in terms of biodiversity conservation.

What happens to cause a green design to fail?

The problem boils down to the fact that there is a huge emphasis on site design but little attention is paid to the construction and postconstruction phases.

Of course, site design is very important and one must conserve the appropriate green infrastructure, which translates (among other things) to a compact design where significant natural areas are conserved and connectivity is built across landscapes. Whatever is on paper, though, is only the first step. Construction activities can destroy the conservation areas carefully identified during the design phase. A host of contractors and sub-contractors, with a variety of equipment and heavy earthwork machines, can wreak havoc. Examples include:

• Earthwork machines run over the root zones of conserved trees, effectively killing the trees.

• Construction vehicles park or drive through natural areas, compacting the soil and even spreading invasive exotic plants.

• Silt fences are improperly installed and managed, causing nutrients and sediments to choke nearby wetlands.

• Chemicals and materials on site are improperly managed, changing soil chemistry and killing conserved vegetation.

Even if the design and construction phases went well, over the long term, successful biodiversity conservation is dependent on how people manage their homes, yards, and neighborhoods. The below actions can dramatically compromise the biological integrity of a green community:

• Large amounts of fertilizers and pesticides applied on yards, causing the pollution of bodies of water and killing non-target species (e.g., butterflies).

• People release invasive exotic plants and animals, including cats, killing wildlife in nearby habitats.

• Homeowners remove native plant landscaping and replace it with turfgrass and exotic plants.

• Conserved areas are compromised by improper recreation activities, such as people riding ATVs throughout a designated conserved area.

A Way Forward

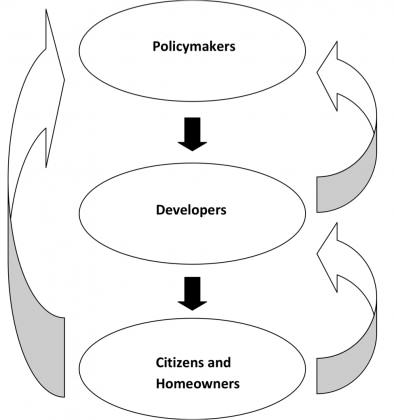

How do we create functional, biodiverse communities? First, a range of stakeholders must understand the dynamic relationship among the three phases of development: design, construction, and postconstruction. Policy makers, planners, regulators, tree survey companies, and green certification agencies must not only create the enabling conditions for a good design, but set in motion incentives and regulations to promote good construction and postconstruction practices. Built environment professionals (including landscape architects, contractors, civil engineers, etc.) need to adopt alternative design, construction, postconstruction practices.

Most importantly, each of us needs to know how to evaluate the “greenness” of a community in order influence future green developments. Collectively, through purchasing power, negative and positive feedback will help raise the bar on what is a green development. The “functionality” of a green city or neighborhood is directly dependent on our actions, and we should reach out to neighbors to share and demonstrate green ideas.

I am utterly convinced the way forward is dependent on creating working models of “green” developments, from whole subdivisions to individual yards, in each county and neighborhood across the country. Do not underestimate the power of a local example. Nothing speaks more to increasing the uptake of alternative designs and management practices than examples that people can see and discuss. I have found building that first, local green subdivision helps to showcase green development practices and provide a catalyst for future developers to adopt new practices. To help promote biodiversity conservation in subdivision development, I recently have written a book titled, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development (University of California Press). This book contains a host of strategies and case studies to create model conservation developments.

I am utterly convinced the way forward is dependent on creating working models of “green” developments, from whole subdivisions to individual yards, in each county and neighborhood across the country. Do not underestimate the power of a local example. Nothing speaks more to increasing the uptake of alternative designs and management practices than examples that people can see and discuss. I have found building that first, local green subdivision helps to showcase green development practices and provide a catalyst for future developers to adopt new practices. To help promote biodiversity conservation in subdivision development, I recently have written a book titled, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development (University of California Press). This book contains a host of strategies and case studies to create model conservation developments.

The time is ripe for action; the current low in the housing market allows some breathing room to discuss and set in motion new ways for communities to grow. The leap towards a new path is not complicated, but it will take a concerted effort from a variety of folks. I welcome comments and even examples of urban biodiversity conservation in your towns and neighborhoods.

Mark Hostetler

Gainesville, Florida USA

Editor’s note: this blog was also published as a Huffington Blog post

Leave a Reply