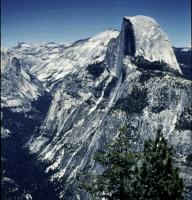

It is interesting that we think of nature in cities only as fauna and flora. Mineral nature—the rocks and inert resources—is the stage on which living nature is set. In cities, this means that the embedded nature all around us, that has been extracted from the Earth like the processed aggregate that we use to make concrete, or the oil (decomposed plants) we lay down for our streets as asphalt, are excluded from the conversation about nature in the city, or city nature. What is it about mineral, inert nature that surrounds us in the city—and is used to create the infrastructure we depend on like buildings—that it gets no attention? We make pilgrimages to see Half Dome in Yosemite, or admire the Palisades along the Hudson River, but the transformation of this inert nature, the rocks, gypsum, iron ores and other metals and minerals, timber and asphalt, are never considered as part of the nature in cities. They are often seen as in the way of planting more trees, allowing water to infiltrate into the soil, and to creating more green open space.

What would happen to our view of city nature if we began to be aware of all the embedded inert nature in urban areas and consider the enormous resource value they contain?

Inert nature, the materials that make up the city and every object in our daily lives, is almost incomprehensibly ubiquitous, and valuable. It represents a sunk investment, sunken fossil energy, sunken human energy, sunken materials that can only be reused (if at all) by applying more energy, labor and ingenuity. Many of the materials are already highly energy intensive, like concrete, aluminum, steel. Energy that is often fossil energy, and to reuse them means more fossil energy expended. These mineral resources in cities are predicated on a vast exploitation of Earth ecosystems and resources. Should we begin to treat this embedded mineral nature with more awareness of what it represents relative to the exploitation of natural resources, ecosystems and people, it might lead to new ideas about how to make cities more sustainable.

The ubiquitous way in which sunken infrastructure is invisible can be seen in the way modern ecology has turned its back on the interactions between natural and modern industrial systems, just like much of neoclassical economics has ignored the physical and biotic underpinnings of economic production. Economic production is treated as sui generis, subject to its own rules and not to natural scarcities or pollution impacts on future biotic or physical resources. Ecologists have little to say about modern industrial systems, despite those systems being derived from, and built upon, physical principles and elements (Hall, Cleveland and Kaufmann 1992). Sustainable city literature seems to have done so as well. Ecological footprint analysis, that measures embedded energy in the city, still does not seem to make us appreciate the actual mineral materiality in our every day urban lives. To realize how much Earth resources our existing cities contain, and to begin to consider those transformed resources as part of city nature, could transform our relationship to the city’s infrastructure.

One of the myths supporting the invisibility of nature in infrastructure is that technological advances and human ingenuity make the issue of resource availability and resource quality irrelevant (Hall, Cleveland and Kaufman 1992). Though modern technology has made the link between natural resources and human existence less apparent, we are still as dependent as ever on the extraction of natural resources to make material goods, and to build infrastructure. The lack of awareness of the processes and impacts of resource exploitation and the often profound disruptions in the ecosystem where that deposit is located, regardless of its scarcity, enable a kind of cavalier approach to the built environment, where not only do we build carelessly as to the local impacts on natural systems, but we are wasteful of Earth resources, building cheaply knowing that things will be torn down and rebuilt in the next economic cycle, or by the next property owner, or that with enough heating and cooling energy expended, the quality of the construction does not matter.

Yet, true resources are expended in rebuilding, resources from nature that come from somewhere. Just like cutting down mature street trees is wasteful, so is our churning of the urban fabric to maximize the next real estate cycle. So, to better take this situation into account, we need to comprehend that the mineral hard surfaces of the city are city nature too. This calls for consciousness in what we use to build, how we build, and ensuring the longevity of that investment.

Over time, as resources become rare, or dissipated, the more energy will be needed to extract them. Geological factors ultimately determine the amount of energy needed to exploit a resource deposit and humans can apply greater and greater fossil energy to extracting resources—to a point. Ultimately there are diminishing returns and the resource is too dissipated to be exploited in any reasonable manner. There are changes in quality of the resource with increased rates of exploitation. All this is important to keep in mind when thinking about the nature in cities and sustainability.

What has already been extracted and transformed into usable materials must be valued for what it is: largely unrenewable. For example, copper deposits, once exploited, do not regenerate. Copper in infrastructure provides important services, it has to be conserved, reused, well managed. Plastics, such as for pipes, may be more abundant since we still have fossil energy, but once disposed of are unrecoverable, and pose disposal challenges.

Understanding that cities are nature—including an inert nature that is harvested, extracted, mined, reprocessed and made into our roads, buildings, pipes, roofs, wiring, doors, windows, mechanical systems, and more—is sobering. It means we need to be thoughtful when we advocate for new LEED buildings, or Zero Net Energy buildings. It means that any new infrastructure, including public transportation infrastructure, means more capturing of mineral nature and the application of fossil energy, to make it and to place it in existing infrastructure, ripping out the existing infrastructure that will then need to be disposed of. All that rubble originally came from somewhere, whose extraction damaged ecosystems.

One approach to better determine how to retrofit the existing built environment is to begin to employ new tools like life cycle analysis more systematically, to reveal the already invested materials and energy in what we have built. Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) is a cradle to grave energy and materials accounting method that reveals the existing sunk costs. Conducting LCAs to better evaluate choices in approaching the already built environment could lead to better use of existing cities, densifying them, repurposing existing buildings, reworking existing transportation corridors, and appreciating the degree to which the cities we live in are expressions of nature in and of themselves rather than disregarding the resources already mustered in what we have built already.

In Los Angeles we have a research project attempting to quantify the city’s urban metabolism—the energy flows in and the waste flows out—in greater granularity and specificity. Concerned with understand the energy and materials already existing in the built environment, we are using county tax assessor parcel data that includes building age, size, type, and material make up. Based on this information we are creating a life cycle assessment of the embedded energy in 27 different building types to begin to account for the nature that we have already used and are living in.

This type of accounting may help in determining the true cost of new building, especially on green fields, and urban retrofitting. We are still in the process of developing the calculations on the LCA of the building types, but according to new studies, there is evidence that retrofitting existing infrastructure for energy conservation has lower life cycle impacts than building new energy efficient buildings – except for warehouses. This adds to the argument that building on green fields is generally less efficient than infill. Additionally, as there is plenty of land already annexed in most American cities new population growth should be accommodated where there is already infrastructure. So, if already existing infrastructure is retrofitted and urban space better utilized, the pressure on virgin resources, and on ecosystems will be lessened. While ecological footprinting has already shown the Earth impacts of cities, it has not really been used to examine the amount of nature captured in city systems; life cycle tools are useful in this regard.

In the end, our immersion in nature is inescapable, even in what we perceive of as the most non-natural of environments—cities. Once this realization starts to change we can really begin to appreciate the nature of cities and treat the mineral resources of cities as lovingly as fauna and flora.

Stephanie Pincetl

Los Angeles

Leave a Reply