Yesterday upon the stair

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

Oh, how I wish he’d go away

— William Hughes Mearns 1922

Learning to forget

When the early settlers headed west across the American continent their cultural baggage weighed lightly when it came to reading the landscape. Oak trees were recognisably oak trees and the pathways made by the first peoples bore the same legibility and logic as trails through European woods; so they followed them, and assimilated them into their own transport networks. In 1847, Cayuga chief Wa-o-wo-wa-no-onk observed that the land of the ‘Empire State’ was “…once laced by… trails worn so deep by the feet of the Iroquois that they became (the settlers’) own roads of travel…” (McLuhan p.100).

Old ways may have been forgotten but memory is the essential substrate of culture. Some memory of the paths made by the Cayuga remain etched beneath the blacktops of New York. Memory, in the form of books, transcripts, recordings, oral history, song and building is how we transfer essential information from each generation to the next. Each generation doing something like their predecessors did with imperfect recollections, passing on patterns of the past. So cities and architecture evolved over time on the foundations of things that people have found to be functional. Wipe that memory clean and a subtle form of chaos begins to take hold. A society that forgets its history is like a person with dementia — trying to orientate themselves and live competently in the present without the benefit of being able to draw on years of accumulated knowledge and experience.

Too often, when we construct our human nests and lace our habitat with roads and sewers and all the paraphernalia of infrastructure we forget history’s lessons and no longer follow well-worn paths made with the inter-generational logic of ancient trails. The best we manage is to follow the guidelines of rule books (albeit they are also the consequence of cultural record keeping). As a result, our newest cities and urban spaces tend to be delivered with little palpable sense of place and with a kind of emotional emptiness. Modernist experiments like Brasilia perfectly express the kind of alienated thinking that has ruled the way we have shaped and reshaped our cities since the early 20th century, abandoning the intuitive evolution and understanding of place in exchange for an abstract set of rules derived from crude, simplistic, early-industrial logic.

How and where we live is crucial to the health of the natural environment and to our well-being. Modern humans have evolved to need shelter to the point that, unless specifically trained to do otherwise, we cannot survive without it. Yet all too often, the mainstream disciplines of architecture and planning offer superficial views of the built environment in which design is about making fashionable choices of cladding whilst communities are mostly disregarded and the natural world is treated as an inanimate backdrop to design rather than a living system that encompasses it.

Efforts to understand the ecology of the built environment is muddled by the kind of revisionism that sees an architectural culture hero like arch-Modernist Le Corbusier, who celebrated the city as ‘an assault on nature’, as a prototypical ‘green’ architect (Farmer 1996). One might reasonably ask how architects and planners can hope to see past such sophistry, stuck as they are within the frame of a severely damaged picture of the world.

As if the absence of memory was somehow cleansing and good, the enterprise of Modernism has always trumpeted the joys of kicking over the traces of the past and celebrated the triumph of the new over the old. Anxious to prove its superiority, Modernism has long conflated ‘new’ with ‘freedom’ and ‘progress’ and confounded attempts to conserve the old by portraying it as reactionary. We have learned to forget lest we become somehow corrupted by the past. The preferred canvas of Modernism is a tabula rasa, a place like a blank sheet of paper, without definition or limits. Lost in this indeterminate ‘space’ fetishized by Modernist architectural and planning training, the practice of design is restrained only by the limitless bounds of a designer’s ego, whilst the facts of life and the natural limits of place are willfully ignored.

However, natural systems don’t have the luxury of being able to ignore what designers choose to practice and try as we might, there is no way to maintain civilization outside of the constraints of the actual context of place.

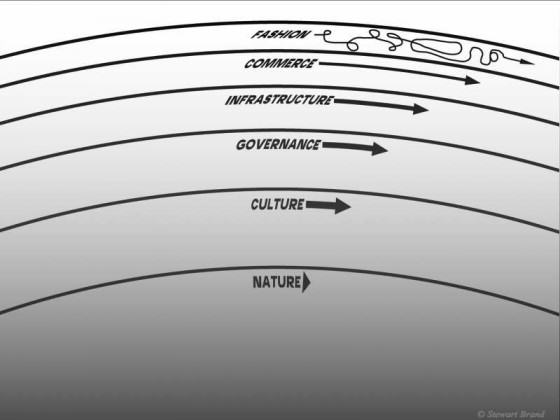

Layers of Change

Stewart Brand explored how different rates of change apply to the various layers that make up civilisation. The ‘slowest’ layer is nature. That’s where we find the slow churning of geology and climate. Resting on that is culture. The fundamental settings of culture are determined by the nature of the environment in which the culture evolves, so desert customs and technologies are markedly different from those associated with rain forests. Culture changes faster than nature. Then, with increasing pace, comes governance, infrastructure, commerce and the flibbertigibbet of fashion. At least that’s how it used to be, maybe for ten thousand years — since the beginning of civilisation.

But in the Australian ‘Age’ newspaper in October 2007, Rachel Wells reported that leading international fashion designers and industry experts were claiming unpredictable and typically warmer weather worldwide was wreaking havoc on the industry and the whole fashion system would have to change. “So worried are some fashion houses about the impact climate change is having on the way we dress and shop,” said Wells “they are calling in the climate experts.” Brand’s layers of change have suddenly flipped. The climate is changing faster than the fashion industry.

Not only is the climate changing, the nature of every place is being systemically undone by ecological poverty as human disturbances range from the introduction of pest species to the clear-felling of ancient forests.

(c) DJTaylor / www.fotosearch.com Stock Photography

What used to be the world’s fourth largest lake, the Aral Sea, has all but dried up. People are being dispossessed of places that have shaped their lives and old certainties are turning into conundrums. In the face of such changes, it is no wonder that some resort to denial. Losing your place is disorientating.

Despite the gloomy evidence that we are better equipped to diminish or destroy the quality of places rather than enhance them, or perhaps because of it, I would argue that there remains a profound need for maintaining a ‘sense of place’ and responsiveness to place in the making of our built environments. There are sound reasons to reinforce whatever skerrick of sense we might have about where we live. Like the thread of an ecological corridor in a degraded landscape maintaining the connections of diversity and life between human-sundered species, even the slightest sense of what a ‘place’ might have been can catch the thread of memory and pull us into its orbit. Humanity is part of nature, after all.

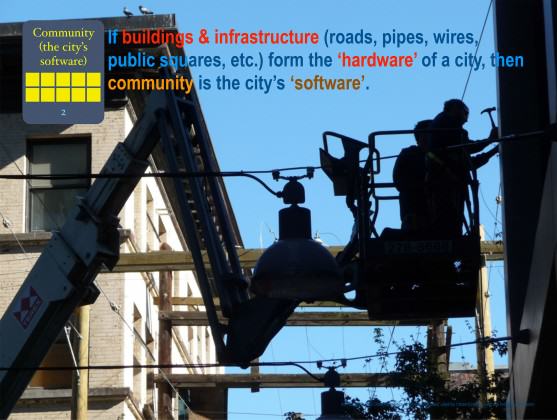

And humans are integral to the ecosystem that is a city. An unoccupied urban environment is different from an occupied urban environment — one is a mere assemblage of physical stuff, the other is alive. One can be studied by an archaeologist, the other demands the attentions of an ecologist. Pioneering urban ecologist Ian Douglas wrote about the difference between the civitas – the functional, cultural entity, and the urbs – the physical entity. Douglas proposed that “No biophysical study of the city can… be divorced from the ancient view of the city (polis) as a political conception.” (Douglas 1983). To reinforce the idea that there is a difference between the inhabited and uninhabited states of buildings and cities, in a presentation toolkit I put together recently for Urban Ecology Australia I described the physical built environment of the city as its hardware, and community as its software.

Off with their heads!

Cities occupy territory and gradually change it. Industrial civilisation has taken that process of change and put it on steroids. Symbols of the ‘old’ become unwanted, even hated, as brave new worlds jostle for attention. Modernists don’t like pitched roofs because they symbolise another time. Even in climates that command the logic of tilted planes to shed rain or snow the Modernist passion to cut clean across the skyline runs unfettered, slicing off the determinedly irregular patterns of the past in favour of the indeterminate horizontal line. Clearing the city’s collective memory of its weather by decapitating it.

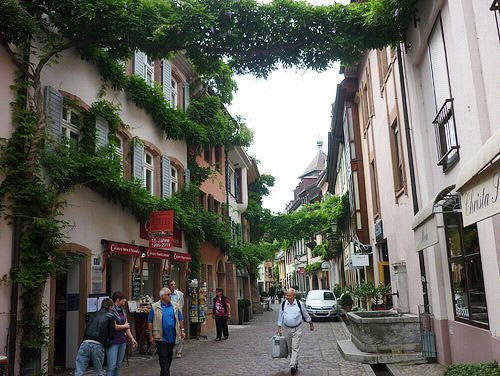

After the Second World War, eschewing the conventional logic of the time, which favoured a Modernist rebuilding agenda that would rid it of the past, Freiburg recognised that its history went back much further than the years usurped by Nazism and set out to reclaim its heritage and its memory. Its citizens took to hard-wiring the city’s built form as a memory of what it used to be. It was very unfashionable — and it has proved very successful in creating a city with a strong sense of itself with progressive communities that harbour the resilience and determination to tackle, amongst other things, the challenge of climate change.

To restore the deeper memories of place we need to go back beyond the cultural baselines established in more recent times. In his book ‘Feral’, George Monbiot writes elegantly and powerfully about the concept of ‘rewilding’ in which nature is given the opportunity to restore landscapes by letting them evolve without heavy-handed management — without, in effect, being shaped by the prejudices of human culture.

On those terms, is rewilding possible in our cities? We have seen the introduction of meadow lands instead of ‘conventional’ parks in many cities including, Dublin, London’s 2012 Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and Bristol, England, where at least there is some memory of its pre-urban past as “Many hedges several centuries old survive in Bristol, and many of the city’s older streets follow the lines of hedges they replaced.” The Shifting Baseline Syndrome (see below) is alive and well as the Bristol City Council website has that piece of information listed under ‘Fascinating facts about Bristol’s wildlife’ (my emphasis). Hedges (and most meadows) are anything but wild.

There is a need for wildness in the heart of civilisation, there is a need to maintain some threads of historical continuity and there is a need to try and recover a sense of how the world was before the baselines shifted. These things, once discovered, are like itchy wounds; they are irritants reviving the memory of a previous condition and with luck, like an itchy wound, the itch could be a sign that the damage is being healed, provided it isn’t scratched away.

And if we were to rewild our cities, how far back do we go? Some say there were elephants in Europe just a few thousand years ago. There were certainly wolves. Wolves are being reintroduced to landscapes in Europe and North America — is it even possible to conceive of cities that include wild wolves in their cityscapes?

To do so, a cultural shift is needed.

Evoking place

The evocation of a sense of place can come from small, specific memories. Using reclaimed bricks and masonry pillars, the verandah along the street front of Christie Walk’s largest apartment building is a partial restoration of the verandah that used to front an old house on the site. To those who knew the site before the apartment was built it offers a trigger for memory from which can cascade stories about the place. For those who never knew what was there before, it provides the basis for asking questions about the place and its history.

The evidence that people want to hold on to the past remains strong. Sadly, that evidence is often in the form of debased replicas of old things and places, or the memories of words and meanings applied to things that bear no relation to their origin. Whereas specific memories can evoke a particular sense of place, generic ‘pseudo-memories’ of place corrupt its very essence — one thinks of shopping ‘villages’… Is it possible to recover the deeper past as a means of informing the making of the present?

Solastalgia and the Shifting Baseline Syndrome

In a world that’s quickly heating up and drying up, you can’t go home again — even if you never leave.

— (Thompson 2008 p.70)

Making architecture and building cities is about manipulating the material and processes of the natural environment to create artificial places of firmness, commodity and delight. When those manipulations took place relatively slowly (several hundred years in the case of medieval cathedrals) people were able to adapt to their changing environments whilst maintaining a sense of belonging and of being in place. With more rapid change those senses become unanchored and fossil-fuelled industrial society has been delivering accelerating rates of change for over two centuries.

Developments like open-pit coal mining rapidly and radically change familiar environments and can create a sense of displacement so severe as to raise suicide rates. Climate change may seem to have barely begun but it has already brought about such rapid changes in the natural environment that people in some places are reported to be feeling a “deep, wrenching sense of loss as they watch the landscape around them change.” (Thompson 2008 p.70). Environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht’s word for this “new type of sadness” is solastalgia: “the pain or sickness caused by the loss or lack of solace and the sense of desolation connected to the present state of one’s home and territory. It is the ‘lived experience’ of negative environmental change. It is the homesickness you have when you are still at home.” (Albrecht 2008). Albrecht describes the syndrome as “that feeling you have when your sense of place is under attack.” His more formal definition is that solastalgia is “an emplaced or existential melancholia experienced with the negative transformation (desolation) of a loved home environment.” And he suggests that with the speed and spread of environmental change, particularly that associated with shifting climate regimes, it is going to become much more common.

Whilst the on-the-spot remaking of places might afflict individuals with solastalgia, the flip side of that remaking is the creation of new baseline normalities for each generation — the ‘Shifting Baseline Syndrome’. The term, according to George Monbiot, was coined by fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly to describe a kind of collective amnesia in which “The people of every generation perceive the ecosystems they encountered in their childhood as normal.” Monbiot cited Pauly’s term to reinforce his argument that many of the supposedly ‘wilderness’ landscapes of Britain are, in truth, severely degraded — the bare hills of “sheep-scraped misery” that are the Cambrian uplands were once rainforest. In the same way, the climate that has been experienced since childhood by anyone in the younger generation is different from the climate that us older folk are likely to recall from when we were growing up.

This is even more true of the villages, towns and cities of childhood, almost anywhere across the globe. As populations have increased, urbanisation has accelerated, technologies have shifted, and the shape of daily life in the world’s towns and cities has changed. What people remember as ‘normal’ varies between generations, what they think of as ‘traditional’ depends on how old they are — if traditional used to mean ‘what our great-grandparents used to do’, it now means ‘what our parents used to do’.

The upshot of this is that, intuitively, we have lost any sense of perspective on history and place. To know what a place is about with any degree of historical depth, we must consciously study and interpret the scattered and damaged evidence of whatever information we can get hold of.

Living-in-Place

Back in the 1970s, the ever-iconoclastic Peter Berg, with Raymond Dasmann, described a phenomenon they called ‘reinhabitation’ and defined it as a process that involves learning to ‘live-in-place’.

‘Living-in-place is an age-old way of existence, disrupted in some parts of the world a few millenia ago by the rise of exploitative civilization, and more generally during the past two centuries by the spread of industrial civilization. It is not, however, to be thought of as antagonistic to civilization, in the more humane sense of that word, but may be the only way in which a truly civilized existence can be maintained.’

Living-in-place, they said, “means following the necessities and pleasures of life as they are uniquely presented by a particular site, and evolving ways to ensure long-term occupancy of that site.” Industrialisation and urbanisation have reshaped and redefined the nature of every place they’ve touched so to get to know the landscape of where a modern city now stands you need to somehow stand in that place as it was before the city was there. We can’t go back in time, so in the absence of a TARDIS, the temporal relocation required has to be all in the mind – fed by whatever data, experiences, fables and history that remains of the original place.

The final boundaries of a bioregion are best described by the people who have long lived within it, through human recognition of the realities of living-in-place.

— Berg and Dasmann 1977

Berg and Dasmann’s concept of a bioregion differs from purely biogeographic or biotic definitions by extending the term to include both a geographical terrain and its related ‘terrain of consciousness’. By incorporating this cultural perception of place the Bergian concept of a bioregion knits human occupation into the fabric of our understanding of ecosystems. It places people firmly in the picture and reminds us that even the idea of ‘wilderness’ is a cultural construct. By seeing the changes in the nature of a place as a continuum of human-induced changes it may be easier to make logical connections between pre-industrial and pre-urban environments and the present.

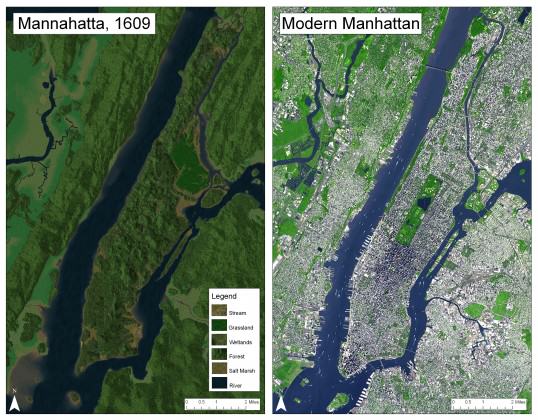

There are ways to recover a deeper sense of place, by understanding the nature of a city before it became a city. Said to be ‘the most detailed scientific reconstruction of an ecological landscape ever attempted’, the Mannahatta Project by Eric Sanderson and the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society is perhaps the best attempt yet to recapture an in-depth sense of what a place was like before being worked over by industrial-urbanism. The project does not explore bioregional terrains of consciousness, but it does demonstrate how thoroughly retrospective mapping can be and provides good evidence for the power of mental temporal time machines.

Shadow Plans

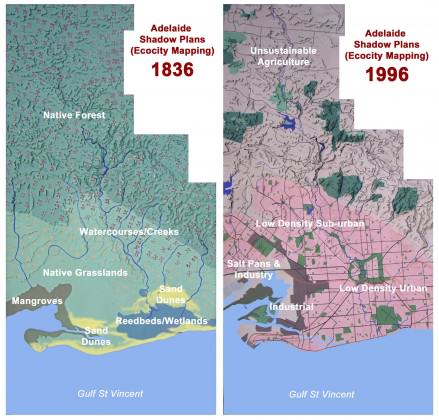

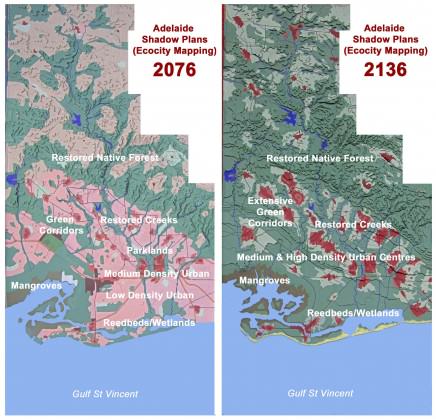

Inspired by numerous discussions and Richard Register’s ‘Ecocity Zoning Maps’ in ‘Ecocity Berkeley’ (1987) I became intrigued by the idea of using physical models of a region to assist in planning and conceptualising the perception of place. In 1994 I ran a third year studio in the architecture program of the University of South Australia called ‘City as Organism’ in which we explored ways to plan for the future of Adelaide’s Tandanya bioregion. Students were asked to look at the city as if it was a living organism and they began by investigating the creeks of Adelaide and trying to imagine the place as it was prior to the arrival of Europeans and urbanisation.

The students then began constructing large scale relief models (2.4 x 1.2 metres) of the River Torrens Catchment, extending from the coast all the way to the source of the Torrens near Mt Pleasant. This was inspired by Register’s proposition that creeks should be restored, and informed by the photographic and historical study, edited by Warburton, of the five creeks which drain into the River Torrens (Warburton 1977). The series of three-dimensional contour maps of the watershed were later completed by volunteers, trainees and interns at the Centre for Urban Ecology (notably Digby Hall and later, Nina Creedman).

In a visit to South Australia to address the 1991 National Greenhouse Conference Richard had observed the phenomenon of a ‘shadow ministry’ in Australian governments and noted:

Shadow ministers belong to the party that is not in power at a particular time. These people are those most likely to assume the ministry positions should a new government be formed…The shadow ministers have great influence and are sought out by the media as key critics of the present administration and are a channel for new ideas into the system.

Following this convention of having ‘plans in waiting’, we renamed the zoning maps ‘Shadow Plans’. They spanned some 300 years, from before Europeans came along and started altering the landscape (1836) to Adelaide’s 300th anniversary in the year 2136. The plans are snapshots along that timeline, intended to show how things might evolve in a society that had reinvigorated its culture of city making with deeper ideas about memory, reinhabitation, ecological regeneration and a sense of place. Although focused on the River Torrens Catchment the plans employ and display principles that can be applied to any bioregion in the world and help us remember where our cities really are and what they could be. As I finish this blog, I’ve been told by David Maddox that Eric Sanderson’s current project is ‘2409’ – a simulator that lets people plan NYC the way they want to see it, with user-editable consumption patterns, and feedback on what ecological results ensue. I’d call that a nicely sophisticated shadow planning tool!

Shadows of the past affect every moment of the present — which is damaged when memories are damaged — while the more we imagine and learn about the way things could be, and the more skillful we become at communicating and sharing those imaginings, the more likely it is that shadow plans of the future can enable us to anticipate the accelerating changes in our biosphere, and form cities that properly reflect the reality that, whether smart or dull, cantankerous or harmonious, humans are part of the functioning nature of the world.

Paul Downton

Adelaide, Australia

Ω

The pen drawings are taken from illustrations I did for ‘The Second Blitz: The demolition and rebuilding of town centres in South Wales’ written by Bob Dumbleton, illustrated by Paul F Downton, published by Bob Dumbleton in 1977 in Cardiff, Wales.

McLuhan, T.C. (compiler), 1973, Touch the Earth, Abacus/Sphere Books, London.

Leave a Reply