Tim Beatley (2000: 224) cites Portland, Oregon as one example of progressive regional, bioregional, and metropolitan-scale greenspace planning in the country. Portland is also known for its land use planning and sustainability practices. Indeed, the city has more LEED (Leadership in Environmental Design) buildings than any other city. While the nation had increased greenhouse gases by 13%, Portland’s fell by 12% between 1990 and 2001. During a comparable period public transit ridership grew by 75% and bicycle commuting by 500%. Between 1990 and 2000 the Portland region’s population grew by 31% but consumed only 4% more land to accommodate that growth. By contrast the Chicago region grew by 4% yet consumed 36% more land (Chicago Wilderness, 1999: 21).

However, until the late 1980s Portland’s urban nature agenda had lagged behind other sustainability initiatives. Competing policies pitted otherwise progressive planning objectives against natural resource protection. Urban planners’ focus on compact urban form and containing sprawl to protect farm land had dominated their thinking. Protecting “too much” urban greenspace, they argued, would result in loss of the buildable lands inside the region’s Urban Growth Boundary (UGB). Many politicians also made this argument. As a result the Portland metropolitan region had failed to adequately protect natural resources within the region’s Urban Growth Boundary (Houck and Labbe, 2007, 40) (Wiley, 2001).

My involvement in urban nature issues began in 1982 when I was approached by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) with a proposal to fund Audubon Society of Portland to take the lead role for inventorying fish and wildlife habitat as part of our statewide land use planning process. Each city and county in Oregon was, and still is, responsible for conducting inventories of their wetlands, open space and fish and wildlife habitat. ODFW felt their resources were better focused on “real” habitat beyond the urban and urbanizing portions of our region. With a $5,000 grant from the state’s nongame wildlife program our new Urban Naturalist Program began work in three counties and twenty-four cities in natural resource protection.

Lessons Learned

Between 1982 and 2007 we engaged with local and regional governments, sewer and stormwater agencies, federal and state agencies, and an emerging NGO network to build support for urban natural resource protection, restoration and management. Presently, we have moved from a planning philosophy which held there was “no place for nature in the city” to where access to nature is now considered an essential element of local and regional planning programs and park and recreation agendas. How did we achieve that shift in thinking? Why are health providers such as Kaiser Permanente and Moda Health, outdoor outfitters, and state and federal wildlife agencies, on board with urban nature programs? There are numerous lessons learned regarding how to mobilize political and public support for an urban nature agenda. The following are a few examples.

Power of the Outside Expert: I met Dr. David Goode, then Director of the London Ecology Unit in London, England at an urban wildlife conference in 1984. We invited Dr. Goode to Portland on five occasions, one of which was to speak at Portland’s premier civic organization, City Club. He said very little that diverged from what we had been saying for the past decade, the fact that he was from London and he spoke with a British accent, accorded him the gravitas that we lacked locally. His presence boosted our efforts considerably.

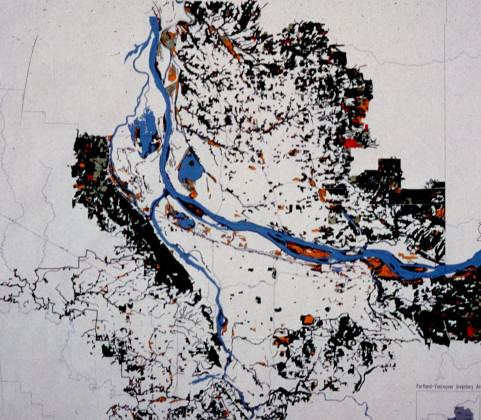

People Love Maps!: Prior to 1989 we had antiquated black and white aerial images of our region’s natural areas. In the spring of 1989 we flew the Portland-Vancouver region with color infrared photography that Portland State University digitized, producing for the first time in our region a map depicting all remaining natural areas. Maps are powerful organizing tools. People love maps! The first response I got when the map was released were angry phone calls, not from people who might have concern about private property rights, but from people who wanted to know why their favorite greenspace was not on the map. I used the map with an acetate overlay to begin generating lists of people who wanted to know the location of the closest greenspace near their home. The map became the rallying point for a regional vision for an interconnected system of natural areas.

Icons are Important: In 1986 I persuaded Portland’s mayor, Bud Clark, to designate the Great Blue Heron as the city’s official bird. While that may sound trivial, each year since Portland’s city council issues a proclamation for the annual Great Blue Heron Week, late May to early June, that spells out what the city will do to ensure herons continue to co-exist with the urban population. It’s our opportunity work with city council to spell out what conservation initiatives we can celebrate having been completed and which ones we will undertake the following year.

Have Fun: The day the Great Blue Heron was adopted as Portland’s city bird several of us met to have a beer at Bridgeport Brewpub, Portland’s first microbrewery. The brewmaster walked by and asked what was new in the world of urban nature. After we told him that we’d just adopted the Great Blue Heron as the city’s official bird he said he’d just brewed a new ale he had yet to name. Voila, Great Blue Heron Ale was born. Again, that may sound trivial, but Blue Heron Ale became the official beer of the Metropolitan Greenspaces movement and Bridgport Brewpub “greenspace central” for meetings, planning sessions, and celebrations.

Build Social Capital: It’s All About Relationships: We have been rigorously intentional about establishing strong, long-term relationships among NGOs, government agencies, and the private sector. Many of those involved in the regional greenspaces movement have known one another for twenty to thirty years. During that time, frequently over Blue Heron Ale, good friendships and trust have been forged. Those relationships and trust have been essential to moving the urban greenspaces agenda forward.

Find Good Models: In our case we took elected officials and park professionals on two visits to East Bay Regional Park District to show an on-the-ground example of what we had been describing. Having elected-to-elected and park professional-to-park professional discussions with East Bay staff and their board provided our elected and park professionals with a fifty-year old system that we could emulate in our region. Our efforts to describe what we wanted to create in our region was made real by using East Bay’s program as a template. Similarly, visits to and by Chicago Wilderness allowed Chicago and Portland to enter into a friendly rivalry and to share best practices. As will be explained later, these relationships have expanded to a national Metropolitan Greenspaces network.

Results

Today, we’ve begun to give serious attention to protecting nature in the city. We’ve passed three regional bond measures totaling more than $400 million to acquire and manage more than 16,000 acres of natural areas within and in close proximity to the region’s UGB.

Stormwater and sewage management agencies have retooled and evolved into broader based watershed health organizations and have begun to incorporate green infrastructure into their formerly grey infrastructure dominated sewer and stormwater programs. No longer mere “sewage” agencies, they now address issues related to state and federal endangered species; they have robust invasive species removal initiatives; and they have recently begun to integrate the natural and built environments at the street-scale and neighborhood scale through innovative, “green” stormwater management programs. And local park providers, such as Portland Parks and Recreation, have re-discovered natural areas as a legitimate element of their parks systems.

Moving To A Collective Impact Model: The Intertwine Alliance

Moving To A Collective Impact Model: The Intertwine Alliance

As successful as our efforts have been, they have for the most part been “one-offs.” For each effort we had to mobilize elected officials, civic leaders, and non-profits anew. Each of these efforts, for example the regional bond measures, required an inordinate amount of sweat equity and financial capital to succeed. By 2007 it was clear that we needed a more sustained, efficient model to carry the work forward.

In 2007 David Bragdon, then President of the Metro Council, convened leaders from around the region and brought leaders from around the country, including Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, for a Connecting Green symposium. The parks visionaries from around the US told their stories, and the lesson was clear. Behind every significant achievement, whether it be the completion of Millennium Park in Chicago or the River Ring trail network in St. Louis, there was a common denominator. Behind every accomplishment stood a coalition of public, private and nonprofit organizations and leaders.

With new inspiration and a clear confirmation of the power of the coalition model we set out to grow our coalition and to make it permanent. We thought: “rather than put this coalition together each time we want to do something big, why not put it together and keep it together and keep doing big things?”

The coalition started with four committed partners and quickly grew. Metro Council President David Bragdon and the Metro Council* took the emerging coalition under their wing for its initial four years, giving it time to grow and get stronger. The Alliance launched as a 501c3 on July 1, 2011 with 28 partners. In less than three years it quadrupled in size to 112 public, private and nonprofit partners.

* Metro is the only directly elected regional government in the United States. By law all twenty-four cities and three counties within its jurisdiction must amend their local plan to conform to the region’s land use planning, transportation, and natural resource regulations. Metro is an important convener of parties with interests in issues or regional importance (www.oregonmetro.gov)

The scope of The Alliance is broad

The Alliance exists to ensure the region’s trail network gets completed; that our natural areas get restored, and that people of all ages discover they can enjoy the outdoors near where they live. We exist to make our region more attractive to new businesses and to help our existing companies attract talent. We’re here to reduce utility and transportation costs and keep our water clean. Finally, we’re here to help our partner organizations build their capacity and become more successful.

Our coalition is diverse. It includes parks agencies, from the smallest municipality to the National Park Service. It includes nonprofit conservation organizations, active transportation organizations, sportswear companies, chambers of commerce, landscape architecture firms, water utilities, and health organizations. It has become a virtual “who’s who” of organizations that have a stake in more deeply integrating nature into the metropolitan region. While our partners share a commitment to nature, their individual missions can differ significantly and it is not uncommon for our partners to be on opposing sides of a local issue. To succeed the benefits of working together must be greater than the benefit of individual action. The forces bringing us together must be stronger than the forces that divide us. We’ve addressed this in three ways.

Focus on investment and engagement

We found that there are two things that our partners universally agree on:

1) We need to attract new investment in nature and better leverage existing investment, and 2) We need to more deeply engage the region’s residents and civic leaders.

We focus on the big things, investment and engagement, where the power of a coalition is truly needed, rather than the smaller issues that are more easily addressed by individual organizations and where there is less universal agreement.

Attend to fundamentals

Attend to fundamentals

The “lessons learned” outlined earlier apply as much today as they did early in our evolution. Social capital is particularly important. We host two summits per year and they always have a strong networking component. We celebrate our progress and set our sights on the next big thing. We don’t know what our successes will be, but we know for sure we’re going to celebrate them twice a year.

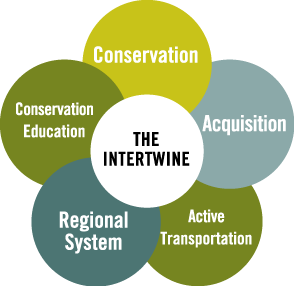

Our vision for the Portland-Vancouver region is made up of many inter-related parts and likewise our coalition is made up of many interrelated groups of interests. For example, some of our partners are primarily interested in building out our region’s trail network. Others are focused on natural area acquisition and restoration. Others operate parks. Rather than pick one or the other, we build and support these individual strands and weave them together into whole cloth. When we started our work, we focused on five issue areas, in the illustration at right. We quickly outgrew this model, and now, in addition to those in the diagram, we support initiatives focused on public engagement, race and equity, economic development, ecosystem services, and nature and health.

All these years we’ve been feeling our way along, trying things, keeping what worked and discarding the rest. We assumed we were pioneers, until we stumbled onto the Collective Impact Model. In 2011 an article appeared in the Stanford Social Innovation Review titled “Collective Impact.” The article described, with academic rigor and authoritative case studies, how the really complex challenges facing society today can’t be addressed by individual organizations working independently. They required coalitions of public, private and nonprofit organizations working in close alignment towards a set of shared outcomes.

Collective Impact is more rigorous and specific than collaboration among organizations. According to John Kania and Mark Kramer, Collective Impact’s originators, there are five conditions that, together, lead to meaningful results from Collective Impact:

- Common Agenda: All participants have a shared vision for change including a common understanding of the problem and a joint approach to solving it through agreed upon actions

- Shared Measurement: Collecting data and measuring results consistently across all participants ensures efforts remain aligned and participants hold each other accountable

- Mutually Reinforcing Activities: Participant activities must be differentiated while still being coordinated through a mutually reinforcing plan of action

- Continuous Communication: Consistent and open communication is needed across the many players to build trust, assure mutual objectives, and appreciate common motivation

- Backbone Organization: Creating and managing collective impact requires a separate organization(s) with staff and a specific set of skills to serve as the backbone for the entire initiative and coordinate participating organizations and agencies

Collective Impact has been enormously helpful to our work in several ways:

- We now have a global network of peers. Practitioners are applying collective impact across the globe to issues from education, to human health, to world hunger. We now have colleagues around the world to exchange best practices with.

- Our approach has been validated. The approach we are taking is now being recognized as best practice when approaching complex social challenges. The United Way has adopted it for their community work nationally. Many foundations are supporting further development and application of the approach and we’re starting to see federal RFP’s calling for a collective impact approach.

- We get new tools. Collective Impact is a framework to guide our work. It is helping us get much more intentional and disciplined about how we guide Intertwine Alliance initiatives.

- There’s a name for what we do. What we are doing is a new way of doing business, which has always made it a little harder to explain. Collective Impact has given us language to describe what we do.

The Intertwine Alliance has sister organizations in other US cities, which have banded together to form the Metropolitan Greenspaces Alliance (MGA). Representatives of The Intertwine Alliance were in Denver March 13 through 15th for an MGA summit and conference. We themed our work at the conference around collective impact. Cities that have or are developing conservation coalitions like ours is almost doubling this year, from seven cities to thirteen. Each is applying the collective impact framework in their own fashion. It should make for a very dynamic and productive era for conservation in urban regions.

Mike Houck and Mike Wetter

Portland, Oregon

about the writer

Mike Wetter

Mike Wetter is Executive Director of The Intertwine Alliance, where he leads a coalition of 112 organizations working to integrate nature into the Portland-Vancouver region.

Leave a Reply