On a path of accelerated urbanization, India is going through substantial changes in its land cover and land use. In 1950, shortly after Indian independence, only 17 percent of the country’s population lived in cities. Today, India’s urban population stands at 33 percent. India contains three of the world’s ten largest cities—Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata—as well as three of the world’s ten fastest growing cities: Ghaziabad, Surat, and Faridabad. In the past two decades, the area covered by Indian cities has expanded by a staggering 250 percent, occupying an additional 5,000 km2 of India’s surface with concrete, asphalt and glass (Nagendra et al., 2013). Projections indicate that more than 50 percent of India’s people will be living in cities by 2050 (United Nations, 2014). This massive urbanization will pose large scale challenges for urban resilience and sustainability, especially for the poorest and most vulnerable: the urban poor, migrant workers, traditional village residents.

“Smart cities,” a program of focus of the Indian government, are considered to hold promise to resolve major challenges of urban sustainability. This approach is driven by a belief in the supremacy of technology for the efficient management of urban growth. Yet other equally, if not more, significant issues of the importance of nature and the restoration of thriving ecosystems for the wellbeing and health of people in cities demand attention. A systematic focus on urban ecosystems, via the protection of urban commons, is essential to provide a robust, adaptive, and resilient pathway towards greater urban sustainability.

The environmental consequences of the rapid growth of cities are starkly apparent. Urban expansion has degraded and destroyed natural habitats across most Indian cities and small towns, transforming urban forests, lakes, and wetlands into polluted travesties of their former ecological vigor, and converting them into vast expanses of concrete construction. Why should we care about the impacts of urbanization on ecosystems? In part, of course, because of their intrinsic value. In addition, though, urban ecosystems are essential for human health and wellbeing and, ultimately, for urban resilience.

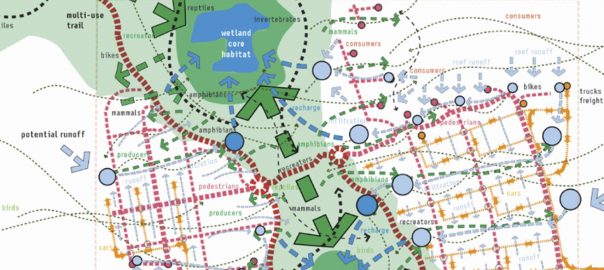

Urban ecosystems provide a range of important ecosystem services that are critical for the sustainability of cities. Wetlands clean up water contaminated with industrial pollutants and sewage, while trees strip the air of pollutants. For instance, coastal wetlands provide protection against flooding to parts of Navi Mumbai, an extension of the city of Mumbai (Nagendra et al., 2013), while inland wetlands buffer the city of Chennai from flooding during heavy rains (Nambi et al., 2014).

Trees in Bengaluru clean polluted air and provide shade for street vendors and pedestrians, reducing the levels of harmful pollutants such as suspended particulate matter and sulphur dioxide (Vailshery et al., 2013). Services such as these are termed “regulating” services because they regulate the environment. Important “supporting” ecosystem services, such as the provision of habitat for migratory birds and bats, are provided by urban ecosystems such as the coastal wetlands of Mumbai and parks in Bangalore (Nagendra et al., 2013).

Urban ecosystems also provide important cultural and recreational ecosystem services. Ecosystems hold an important place in the cultural landscape of urban India through their sacrality and worship (Nagendra et al., 2014). Exposure to green spaces provides wellbeing and psychological relief from urban stress. Parks, lakes and coastal beaches act as important social nodes of congregation, strengthening social bonds between disparate, anonymous urban residents.

The importance of urban regulatory, supporting and recreational services are widely recognized by the public, as well as by policy makers and planners. Yet there has been a systematic decline in the availability of urban ecosystems for provisioning ecosystem services across Indian cities. In almost all Indian cities, lakes, tree cover, grasslands and wetlands once provided food, fodder, fuelwood and other important resources. These ecosystem products are still consumed by many, from cattle owners and fishers to migrant workers and the poor. For instance, the mangroves of Mumbai are used by thousands of local residents for collecting fodder, fuelwood, and food, while lakes in many parts of Bangalore continue to provide fodder for cattle, and supply milk and fish to city residents. These areas historically functioned as urban commons, providing collective resources for the entire community in times of scarcity and need.

However, local planners and governments have permitted the large scale conversion of these areas for urban development. It is only in recent years, in particular after large scale flooding in 2005, that the utility of maintaining mangrove habitats for flood protection and lakes for ground water recharge became recognized, prompting the protection of these habitats (Parthasarathy, 2011). The motivation for such protection has been the urgent need to maintain regulatory ecosystem services, while the importance of production services for the resilience of the poorest and most vulnerable has been largely ignored in official planning discourse. For example, many lakes across Bengaluru are now being restored in response to ground water depletion, following citizen protests by affected local communities.

Yet the protection of lakes has an often ignored, yet important social consequence: while lake ecological condition improves, restored lakes are typically fenced and gated to keep out grazers, washermen (dhobies), fishers and other traditional users.

Urbanization thus not only leads to specific patterns of change in ecosystem use: it also leads to specific types of change in the perceived value of specific types of ecosystem services, shaping wide ranging policies that regulate access to and management of these former urban commons.

Regulatory and recreational ecosystem services have systematically taken precedence over productive uses of ecosystems in the minds of the urban public, the media, and city administration. In turn, urban ecosystems have transformed from commons or common pool resources used by communities for shade, water, grazing, fishing, and fuelwood collection, to protected lakes, parks, and mangrove forests that belong to the state, valued for public ecosystem services such as ground water recharge, recreation, and flood protection.

In this process, many of the urban poor—whose livelihood resilience, health, and nutritional levels depended on access to provisioning ecosystem services—have been the worst affected, losing access to the services provided by natural ecosystems due to the dual processes of privatization for urban land use and public protection for conservation (Mundoli et al., 2014).

The massive scale of urbanization in India will undoubtedly pose challenges for the country’s environment, ecology, society, and sustainability. Responding to these challenges will require sustained attention to devising and implementing appropriate policies for ecologically sustainable urban growth. The current focus on smart cities in India is driven by a search for technological fixes. Yet the restoration of thriving ecosystems as urban commons, which can ensure the wellbeing and health of a wide strata of people in Indian cities, requires equal attention. A systematic focus on urban ecosystems is essential and can provide a relatively inexpensive, adaptive, robust, and resilient approach for enhancing urban sustainability. Better protection, management, and use of urban ecosystems will be essential for urban sustainability in the era of the Anthropocene.

An ecologically smart city may be the smartest city one can envisage! Such an approach would increase the resilience of cities by providing low-cost, adaptive, and efficient ways to deal with the challenges of providing safe food, pure water, and clean air for unprecedented and growing numbers of people. To create ecologically smart cities, a systematic focus on urban ecosystems is required, restoring their original function as urban commons that provide important provisioning, regulatory, recreational, and supporting ecosystem services. Such ecologically smart cities would be low-cost, adaptive, and resilient to a whole host of local and global environmental challenges, from pollution and food insecurity to climate change.

Harini Nagendra

Bangalore

This essay originally appeared on UGEC Viewpoints.

References

Mundoli, S., Manjunatha, B., Nagendra, H. 2014. Effects of urbanization on the use of lakes as commons in the peri-urban interface of Bengaluru, India. International Journal of Sustainable Urban Development DOI: 10.1080/19463138.2014.982124.

Nagendra, H., Sudhira, H.S., Katti, M., Schewenius, M. 2013. Sub-regional assessment of India: Effects of urbanization on land use, biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Urbanization, Biodiversity, and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities, ed. Thomas Elmqvist et al., Chapter 6, pp. 65-74

Nagendra, H., Unnikrishnan, H., Sen, S. 2014. Villages in the city: spatial and temporal heterogeneity in rurality and urbanity in Bangalore, India. LAND 3: 1-18.

Nambi, A.A., Rengalakshmi, R., Madhavan, M., Venkatachalam, L. 2014. Building urban resilience: assessing urban and peri-urban agriculture in Chennai, India. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Nairobi, Kenya.

Parthasarathy, D. 2011. Hunters, gatherers and foragers in a metropolis: commonising the private and public in Mumbai. Economic and Political Weekly XLVI: 54-63.

United Nations. 2014. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York.

Vailshery, L.S., Jaganmohan, M., Nagendra, H. 2013. Effect of street trees on microclimate and air pollution in a tropical city. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 12: 408-415.

Leave a Reply