Long-term sustainability necessitates an inherent and essential capacity for resilience—the ability to recover from disturbance, to accommodate change, and to function in a state of health. In this sense, sustainability typically means the dynamic balance between social-cultural, economic, and ecological domains of human behavior necessary for humankind’s long-term surviving and thriving. As such, long-term sustainability sits squarely in the domain of human intention and activity—and, thus, design. This should not be confused with managing “the environment” as an object separate from human action, which is ultimately impossible. Instead, the challenge of sustainability is very much one for design, and specifically one of design for resilience.

Our approach to resilience has been reactive, with little continuing effort to engage long-term, proactive strategies for adaptation, let alone transformation.

A growing response to the increasing prevalence of major storm events has been the development of political rhetoric around the need for long-term sustainability, especially its prerequisite of resilience in the face of vulnerability. As an emerging policy concept, resilience refers generally to the ability of an ecosystem to withstand and absorb change to prevailing environmental conditions. In an empirical sense, resilience is the amount of change or disruption an ecosystem can absorb and, following these change events, return to a recognizable steady state in which the system retains most of its structures, functions, and feedbacks. In both contexts, resilience is a well-established concept in complex ecological systems research, with a history in resource management, governance, and strategic planning.

Yet, despite more than two decades of this research, the development of policy strategies and design applications related to resilience is relatively recent. While there was a significant political call for resilience strategies following New York’s Superstorm Sandy in 2011 and the ice storm of 2013 in Toronto and the northeastern U.S., this was effectively a reactive approach to crisis, rather than a proactive planning practice. In most instances, once the crisis has abated, there is little continuing effort to engage long-term, proactive strategies for adaptation, let alone transformation—both of which are necessary aspects of resilience, particularly in the context of climate change.

Overall, there is still a widespread lack of coordinated governance, established benchmarks, implemented policy applications, tangible design strategies, and few (if any) empirical measures of success related to climate change adaptation. There has been too little critical analysis and reflection on the need to understand and cultivate resilience beyond the reactive rhetoric and to develop specific and proactive tactics for design. Design for resilience demands proactive planning and an evidence-based approach that contributes to adaptive and ecologically-responsive design in the face of complexity, uncertainty, and vulnerability. Put simply: what does a resilient world look like, how does it behave, and how do we design for resilience?

The emergence of resilience rhetoric is tied not only to the emerging reality of climate change, but to an important and growing synergy between research and policy responses in the fields of ecology, landscape, and urbanism—a synergy that is powerfully influenced by several remarkable and coincidental shifts at the turn of the millennium. Most notable is the global shift in urbanism: our contemporary patterns of settlement are tending towards large-scale urbanization. The last century has been characterized by mass migration to ever-larger urban regions, resulting in the rise of the “mega-city” and its attendant forms of suburbia, exurbia, and associated phenomena of the modern metropolitan landscape. According to the World Health Organization, the percentage of people living in cities is expected to increase from less than 40 percent in 1990 to 70 percent in 2050, and the United Nations projects that in 2030, there will be 5 billion urbanites, with three-quarters of them in the world’s poorest countries. By contrast, in 1950, only New York and London had over 8 million residents. Today, there are more than 20 mega-cities, the majority of which are in Asia. Indeed, for most of the world’s population, the city is fast becoming the singular landscape experience.

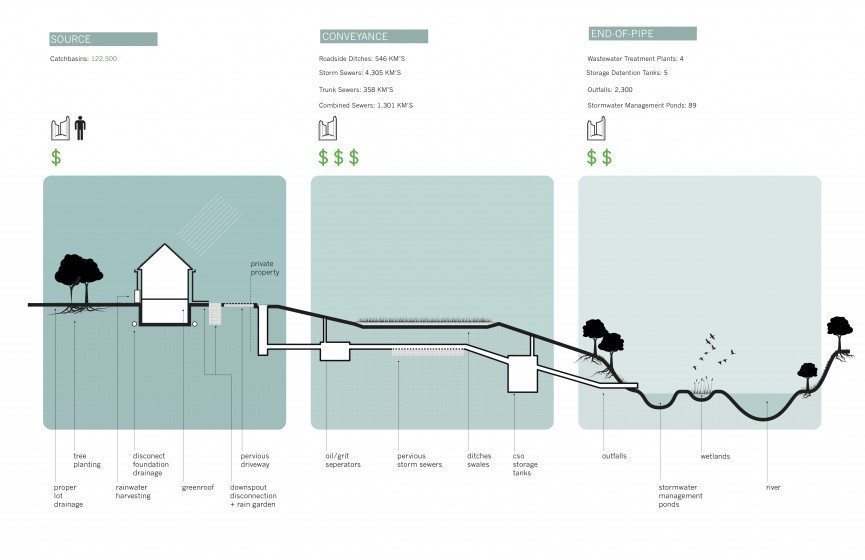

In North America, and the United States in particular, this shift in urbanism has come (paradoxically) with a widespread decline in the quality and performance of the physical infrastructure of the city. The roads, bridges, tunnels, and sewers that were built in the early part of the last century to service major urban centers are now aging (and crumbling), while the political will and the public funds to rebuild outdated but essential public infrastructure are disappearing. As these infrastructures continue to decay, they are increasingly vulnerable to catastrophic failure in the face of more frequent and severe storm events, which compound the cost of their loss and the extent of their loss’s impact.

Embracing dynamism

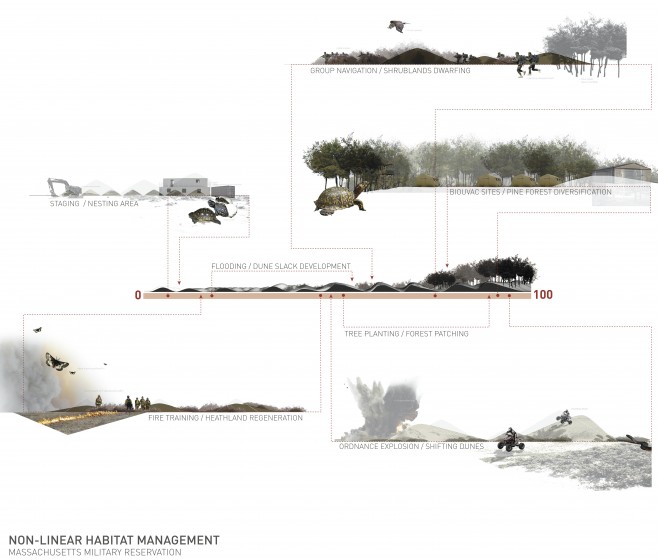

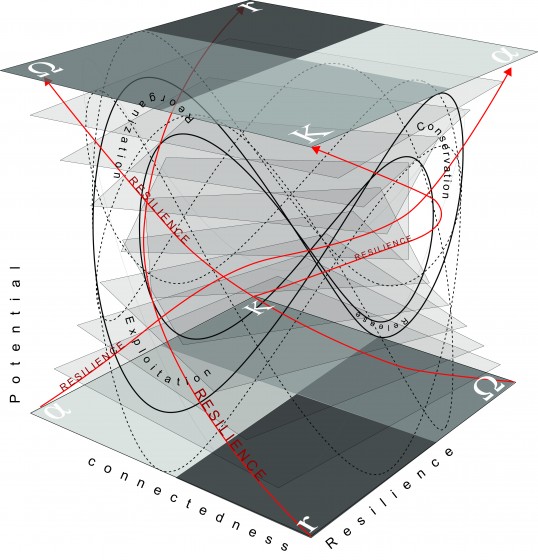

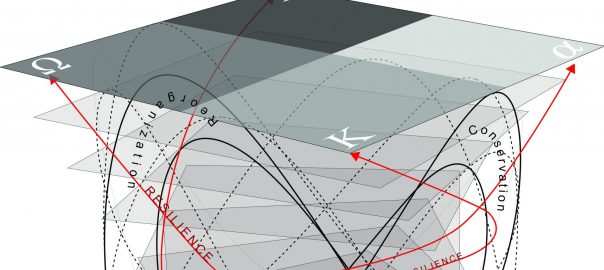

The emergence of a new paradigm in ecology represents another significant and concomitant shift with a change in urbanism and the reality of climate change. In the last 25 years, the field of ecology has moved from a concern with stability, certainty, predictability, and order in favor of more contemporary understandings of dynamic systemic change and the related phenomena of uncertainty, adaptability, and resilience. Increasingly, these concepts in ecological theory and complex systems thinking are found useful as frameworks for decision-making generally, and—with empirical evidence—for landscape design in particular. This offers a powerful new disciplinary and practical space, equally informed by ecological knowledge as an applied science and as a construct for managing change, and, within the context of sustainability, planning for and with change as a conceptual model of design.

With this new ecological paradigm has come another important shift in creating the synergy necessary for resilience-thinking: the renaissance of landscape as both discipline and praxis throughout the last 15 years and its (re)integration with planning and architecture in both academic and applied professional domains. Landscape scholars, such as Beth Meyer, James Corner, Julia Czerniak, and Charles Waldheim, among others, have identified the rise of urban post-industrial landscapes coupled with a focus on indeterminacy and ecological processes as catalysts for the reemergence of landscape theory and praxis. Understood today as an interdisciplinary field linking art, design, and the material science of ecology, landscape scholarship and application now includes a renewed professional field of practice in the space of the city—a phenomenon clearly represented in contemporary design projects.

These shifts in our collective understanding of urbanism, landscape, and ecology have created a powerful synergy for new planning and design approaches to the contemporary metropolitan region. This synergy has been an important catalyst for the emergence of resilience rhetoric, but there is much work to be done to move towards evidence-based implementation of strategies, plans, and designs for resilience. The scale and impact of North American mega-storms such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Superstorm Sandy in 2011 have been effective policy triggers—and design provocation— for a new breed of disaster preparedness planning, particularly for flood management plans.

Recent coastal management policies and flood management plans following these major storm events abound in this language of resilience. The New Orleans Water Management Strategy, Louisiana’s Coastal Management Plan, New York’s Rebuild by Design programme, and Toronto’s Wet Weather Flow Master Plan are examples of notable responses to catalytic storm events and climate change. Yet, they remain predominantly speculative, untested, and unimplemented, relying on a general language of resilience that is conceptual rather than experiential, contextual, or scientifically-derived.

Resilience has origins across at least four disciplines of research and application: psychology, disaster relief and military defense, engineering, and ecology. A scan of resilience policies (see http://resilient-cities.iclei.org/) reveals that the concept is widely and generally defined with reference to several of the origin fields, and universally focuses on the psychological trait of being flexible and adaptable; having the capacity to deal with stress; the ability to “bounce back” to a known normal condition following periods of stress; to maintain well-being under stress; and to be adaptable when faced with change or challenges. However, the use of resilience in this generalised context begs important operational questions of how much change is tolerable, which state of “normal” is desirable and achievable, and under what conditions it is possible to return to a known “normal” state. In policies that hinge on these broadly defined, psycho-social aspects of resilience, there is little or no explicit recognition that adaptation and flexibility may in fact result in transformation—and thus, require the adaptive and transformative capacity that is ultimately necessary at some scale in the face of radical, large-scale and sudden systemic change.

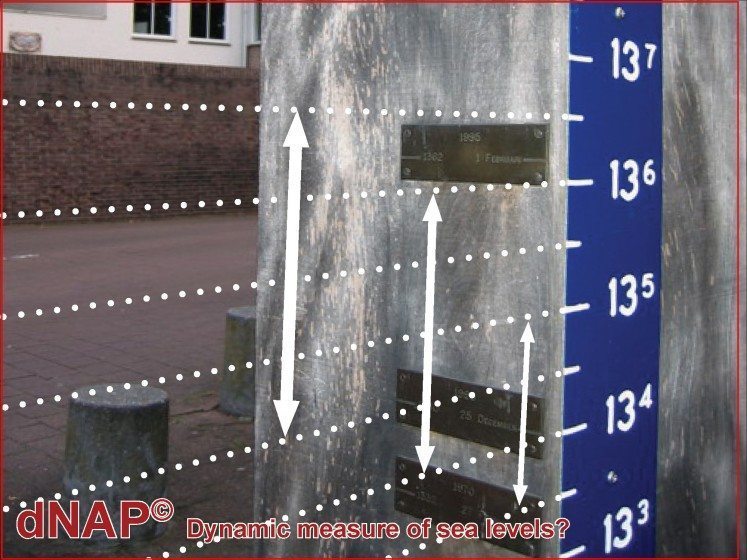

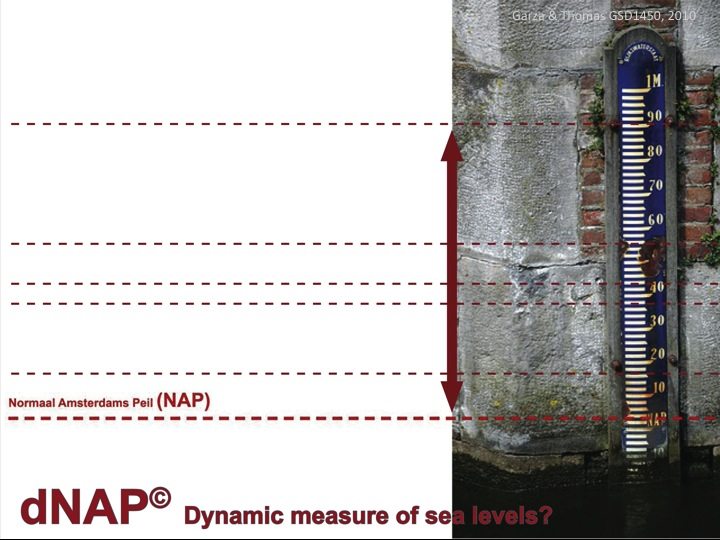

Using sea level as an example, if we accept that waters naturally rise and fall within a range of seasonal norms, we might be better off to embrace a gradient of acceptable “normal” conditions rather than a single static—and ultimately brittle state—that is unsustainable. A more critical and robust, systems-oriented exploration of resilience is necessary, such as the one being developed by Brian Walker, Carl Folke, and others at the trans-disciplinary Stockholm Resilience Centre. This more nuanced, emerging discourse of resilience is essential for confronting the question of how much a person, a community, or an ecosystem can change before it becomes something unrecognizable and functions as an altogether different entity.

Current policies risk the potential power of resilience by emphasizing a misguided focus on “bouncing back” to a normal state that is ultimately impossible to sustain. But if resilience is to be a useful concept in informing design strategies, it must ultimately instruct how to change safely. This includes a need to plan proactively, and to adapt when necessary, with some culturally acceptable risk and loss, and with transformative capacity—rather than to resist change by relying on the illusion of a perpetual normal. Such a subtle but imperative shift in definition caries substantial if not profound implications for contemporary models of governance, in which perceived failure is rarely recognized let alone rewarded as an act of transformative learning. Despite the growth in and acceptance of ‘systems thinking’ in business and governance literature, and the associated rise of complexity science and transition design over the last several decades, there is still high risk and little reward for tangible learning through change. But there are emerging models for infrastructure development and delivery that show signs of promise: private-public procurement, interdisciplinary and collaborative research (via e.g. applied studios, industry partnerships with design) community experiments in design, and growth in rapid prototyping for small-scale projects (emphasizing safe-to-fail rather than fail-safe strategies). These are incremental and often technical steps that cumulatively may demonstrate ‘next best practices’ for more agile responses to changing conditions. Governments must now embrace the social-cultural dimensions of resilience that are essential to building transformative capacity. This is the challenge ahead for a new culture of sustainability and its associated practice of designing for resilience.

Nina-Marie Lister

Toronto

Further reading on resilience & design:

Barnett, Rod, 2013. Emergence in Landscape Architecture. London: Routledge.

Gunderson, Lance and C.S. Holling, eds. 2002. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Socio-Ecological Systems. Washington DC: Island Press.

Irwin, Terry, 2015. Transition design: a proposal for a new area of design practice, study, and research. Design and Culture, 7:2, 229-246, DOI: 10.1080/17547075.2015.1051829

Lister, Nina-Marie, 2016. Resilience beyond Rhetoric in Urban Landscape Planning and Design. In: George F. Thompson, Frederick R. Steiner and Armando Carbonell (eds) Nature and Cities: The Ecological Imperative in Urban Design and Planning. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Mathur, Anuradha and Dilip da Cunha, 2014. Design in the Terrain of Water. New York: Applied Research & Design Publishers.

Reed, Chris and Nina-Marie Lister, eds. 2014. Projective Ecologies. New York: Harvard GSD and Actar.

Steiner, Frederick R. 2011. Design for a Vulnerable Planet. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Resources on Resilience & Design:

Gutter To Gulf: A Water Strategy for New Orleans. www.guttertogulf.org

ICLEI Resilient Cities: http://resilient-cities.iclei.org/

New York’s Rebuild By Design: www.rebuildbydesign.org

Resilience Alliance: http://www.resalliance.org

Stockholm Resilience Centre: http://www.stockholmresilience.org

Leave a Reply