A research and design framework, lowlands looks at public housing projects in environmentally vulnerable locations—specifically, low-lying lands, often on former marshes. A quick survey of New York City public housing projects demonstrates that this is a common condition; in many cases, land available for public housing wasn’t previously developed because of its ecological vulnerability. Historical research, landscape performance, public space politics, design, and community engagement are key elements of the following two projects, one looking at the intersection of green infrastructure and public space, and the other an interactive kiosk

Low-lying urban neighborhoods are vulnerable on a daily basis due to failings of our combined sewer infrastructure.

A little context

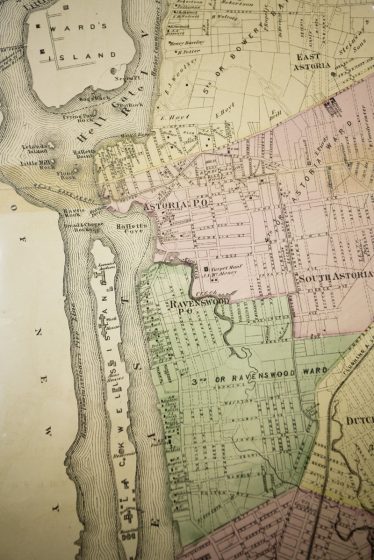

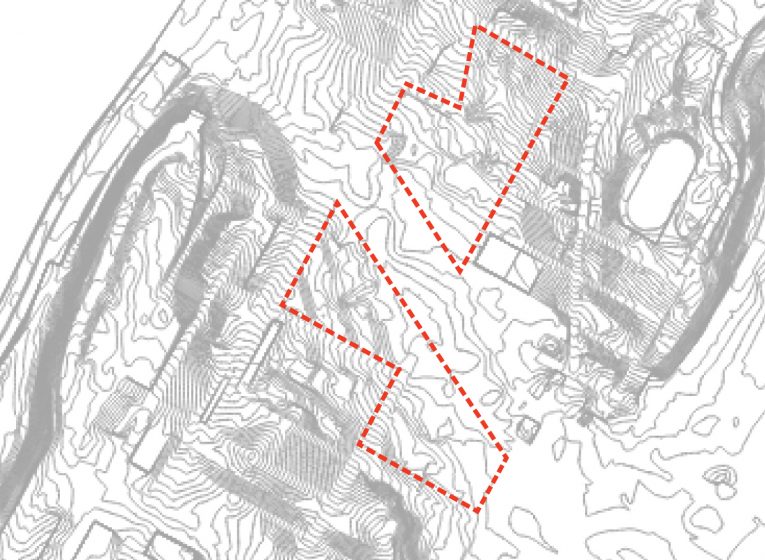

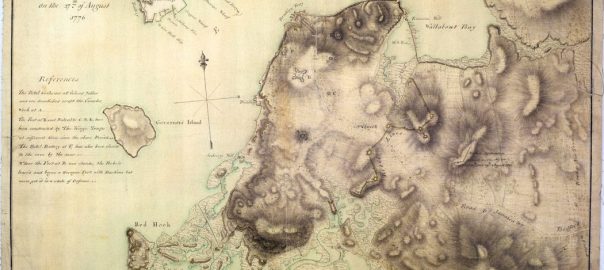

I was working on two speculative projects in New York City—one in Long Island City in Queens and one in the Gowanus area of Brooklyn—during which I was studying historic maps of those areas. I am lover of maps, all maps really, but with a particular affection for topographical ones. I find their fluid lines mesmerizing, the legibility of steep and shallow transforming an abstraction into an imagined physicality. Historic maps, with their odd hatches and nubbly features, communicate folds and ridges in the landscape and the movement of water; topo maps of the past can tell us where water may have once been, now lost or long buried.

![[1] 1776map](https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/1-1776map-700x560.jpg)

In both of these neighborhoods, as is the case throughout the archipelago we call New York City, there were once extensive marshlands. And in both these former marshlands, there are now New York City Housing Authority, or NYCHA, campuses, public housing complexes with multiple buildings and lots of open space. A walk with the official Borough of Queens historian, Jack Eichenbaum, confirmed that the land where Long Island City’s Ravenswood Houses currently are was once a low-lying wetland, with now buried Sunswick Creek running through it. The historic Gowanus Bay and Creek, fully filled in (with the exception of the Gowanus Canal) today hosts two NYCHA properties, the Gowanus Houses and Red Hook Houses.

This got me thinking about the overlap of historic wetlands and contemporary public housing. Low-lying urban neighborhoods are not just vulnerable from one storm to the next, but on a daily basis as our combined sewer infrastructure is increasingly unable to meet the capacity of an expanding city and a changing climate. Such vulnerabilities threaten the viability of our cities: transportation is hindered, homes are flooded, water quality is compromised, and fish and wildlife are threatened. The NYC metropolitan region is increasingly subject to rainfall events above the current 1 inch or less norm. According to Cornell Climate Change Fact Sheet, NYC will experience an increase in average annual precipitation of 5 percent by 2020; 10 percent by the 2050s; and 15 percent by the 2080s; this year has seen rainfall patterns that exhibit these trends.

I am trained as a landscape architect and, along with two fellow Berkeley graduates from the architecture department , Gita Nandan and Mark Mancuso, am a founding principal of thread collective, a multi-disciplinary design firm in Brooklyn, NY. In addition to more traditional built architectural work, we research and explore solutions that require relatively small initial investments and shorter mobilization periods, are integrated and responsive to the particulars of a given context, activate a sense of agency and self-determination, and engage residents in improving the resiliency of their communities. Our designs layer multiple social and ecological benefits, or, to use a Wendell Berry turn of phrase, “solutions that beget solutions.”

lowlands Red Hook

The first iteration of lowlands is a research project focused on the Red Hook Houses, 38 acres in South Brooklyn sited on former wetlands and devastated by Hurricane Sandy. During the summer of 2014, thread collective and Pratt Institute students Acacia Dupierre and Christopher Rice worked closely with the Social Justice Fellows of the Red Hook Initiative to explore the idea of using green infrastructure as a vehicle to develop and improve public space on NYCHA properties. The Social Justice Fellowship is ”a community organizing program for young adults ages 19-24, who work to challenge institutional injustices and bring about positive social change in Red Hook”. How could we leverage the need for stormwater solutions, and the funding available for those solutions, to radically rethink the design of the inaccessible, unactivated lawns that characterize most of public housing’s current open space? And how could our design process create a platform for residents to have a voice in the shaping of their environment?

The scale of NYCHA properties, with their impressive density of mature trees and low pervious-to-impervious surface ratio ensures that they are already positively contributing to the overall ecological health of the city. A conservative calculation demonstrates that around 800,000 gallons of water per year are intercepted, and therefore not directed into NYC’s overtaxed combined sewer system, by the mature trees alone on the two Red Hook Houses sites. How could this role within the neighborhood be further enhanced? Over half of the site, about 25 acres, comprises pervious, fenced-in grassy areas. In addition, there is potential for adding close to 19 additional acres in stormwater capture by retaining or detaining water from building rooftops, impervious sidewalks, and parking lots. Together with the Social Justice Fellows, we developed a set of recommended interventions to create beautiful, socially active places for the residents and to reframe public housing campuses as local assets for their surrounding communities.

![[4] dutchkillstour](https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/4-dutchkillstour-854x560.jpg)

[2] “green infrastructure everywhere”,

[3] access to more diverse activities, such as movie night at the basketball court, outdoor fitness spaces, where you can “sweat and then feel the breeze”, and [4] affordable retail within walking distance—food, particularly, but also beauty salons and banks, and pop up markets for “people to sell things they make”.Other specific design ideas included a Welcome to Red Hook sign, an urban beach, and a craft market in the slightly derelict arbors that bookend the Centre Mall. Old warehouse spaces of Red Hook were re-imagined as spaces programmed with activities that appeal to the youth of Red Hook Houses, including an indoor skating rink and a LGBTQ center.

![[5] charrette](https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/5-charrette-420x560.jpg)

Rethinking Movement included an analysis of both the pathways in the Houses and the city streets, improving circulation, and improving public space through the introduction of green infrastructure. For example, Centre Mall, deemed a tedious and somewhat unsafe space by the Social Justice Fellows, is recast as a linear stormwater garden, maintained by a stewardship program connecting older residents with youth. A preliminary calculation shows significant stormwater capture potential: during a 1 inch rain storm, capturing water from the Red Hook Houses rooftops yields approximately 210,000 gallons, with an estimated 9 million gallons over the course of the year. The current topography supports the movement of water toward the Centre Mall, adding surface runoff to the overall calculation.

![[6] streetendplay](https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/6-streetendplay.jpg)

Red Hook lowlands remains a research project, a set of recommendations that integrate green infrastructure and true public space at a particular NYCHA campus. We are currently developing a set of metrics to assess existing ecosystem services throughout NYCHA property in order to demonstrate, in turn, the current ecological value of these large green spaces and the opportunity to dramatically increase this value through the design and implementation of robust stormwater strategies.

We began the project with an academic understanding of the broken windows policing theory and how it is being applied at NYCHA properties. But the stories from the Fellows made it vividly clear how much the open space use in the Red Hook Houses’ is curtailed by NYCHA policy. Anecdotes included grandmothers gathering with their young grandchildren on a hot summer evening rudely told by the police to go inside (all NYCHA parks close at dusk), and groups of friends being accused of “plotting something”. And as reported recently in the New York Times, “In New York housing projects, police officers can demand identification from people who are hanging out in a public space, like a building lobby. Even if they prove that they live in the building, officers may cite them for ‘lingering.’ It is not a crime, but it is a violation of the New York City Housing Authority’s rules.” In the same article, a NYCHA resident notes, “We can’t even walk in our own parks,” he said. “It makes no sense.” This is certainly the experience of the young adults we talked with. Fundamentally, the project does require a shift in NYCHA policy, to one that does not criminalize basic social behavior, that develops and supports community programming, and that allows open space to become true public space. Now is the time.

lowlands West Harlem

125th street in West Harlem does an odd thing: it diverges from the strict grid that organizes most of New York City, suddenly angling north just before Morningside Avenue. The nature of the shift becomes very clear when one looks at the topography of the area. The street turns to follow a natural valley and former waterway. Known as Moertje David’s Vly during the Dutch era and Hollow Way during the Revolutionary War, the valley was once marked by a series of small creeks, being both an area of inundation from the Hudson River and drainage from the surrounding high points.

![[8] mvilllcreeks](https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/8-mvilllcreeks-762x560.jpg)

West Harlem Climate Action Kiosk

As noted in the NMCA: “After Hurricane Sandy, locally produced signage played an important role in connecting people with networks and resources that supported recovery efforts. Public signs and stands should be created across the City to provide information on cooling center locations, evacuation zones, and other important resources.” Building on this recommendation, thread collective, in collaboration with WE ACT, has recently begun an intensive community design process that will shape the specifics of this interactive public space installation. The Climate Action Kiosk is being developed through CALL/City as Living Laboratory’s BROADWAY: 1000 Steps project in partnership with WE ACT.

A series of design meetings with local residents will determine highest community priorities for the kiosk, consider ways in which the kiosk can catalyze a conversation about engagement and public space, and link the kiosk with local public health and landscape performance data collection studies. Other project activities with Harlem participants include visiting precedent projects in New York City, and workshops and walks addressing climate resiliency in relation to the local ecological conditions. Design charrettes will be held to explore additional innovative elements of the kiosk, such as rainwater collection and air pollution monitoring. In addition to providing event-specific emergency information for local residents, the information kiosk will be a platform for other issues defined by the community. This may include sharing information about current political issues, highlighting relevant historical events, and/or creating a resource exchange program. The primary kiosk will be located within the public housing projects around 125th Street. We are currently analyzing several sites, with particular focus on working with and highlighting existing topography. Ultimately, our hope is that the concept and process, including developing site-specific responses, be replicated throughout New York City Housing Authority properties.

Conclusion

While large-scale, resource-intensive projects seem necessary given the scale of predicted climate change, we believe smaller-scaled, more nimble and precisely targeted solutions are better for creating cities that are not only capable of bouncing back, but that work actively to make our urban environment better ecologically and more socially just. Government investment in essential environmental solutions can and will have an exponential impact when public space solutions are integrated into the ecological systems. Job opportunities, senior and children’s programming, and youth development must also be linked to ecological improvements, creating long-lasting dividends for NYCHA and NYC residents at the same time.

Elliott Maltby

New York City

Leave a Reply