A review of Why Not Ask Again, the 11th Shanghai Biennale at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai, China, on view through 12 March 2017.

It’s not unusual by any means in the contemporary art world, but as an edifice, the Power Station of Art is just about as apathetic to nature as most any building could be. Typifying the space is the view from the observation deck, proudly showcasing the ability of man to build a massive wall of housing towers.

The societal critiques present at the Power Station of Art point, in many ways, to a maturity and openness we don’t normally associate with China.

Given our position in Shanghai, it’s not a bad view.

To its credit, the building was once, as you might have guessed, a power station. It has since been transformed into a truly impressive space for showing art. The dedication of the Chinese government (and municipality of Shanghai) to building a world-class facility is evident here. Both in this exhibition and in previous shows, the space—where shimmering new walls of glass mingle with leftover industrial quirks and kinks—is used well by the curatorial team.

In many ways, the interplay between nature, industry, and technology is firmly planted in the commentary of the work.

The show’s title, “Why Not Ask Again”, is, itself, telling of what viewers will find here: a deeper questioning of the questions to which we might think we already know the answers. In the West, this might seem a timid title, as this process of re-questioning our assumptions has been firmly installed as one of the key foundations of contemporary art as a practice for a long time. But here in Shanghai, it is gently pushing a boundary—and not so gently, in some cases, as one of the works was reportedly censored out of the show just before the opening. This means the exhibition’s curators are walking the tightrope between showcasing complacent, safe art, and getting booted out of the country. It’s a good sign.

Upon entering the building and being scolded for having a backpack, I am almost immediately drawn to a large circular installation of sand on the floor. Many more are, too: it’s surrounded by curious onlookers.

Walking closer, I see that the work, titled Lunar Station, also comprises a large and heavy looking metal pendulum. It swings slowly and steadily, suspended over the sand by a cable running up the better part of three floors, straight through the guts of the power station. The movement of the pendulum and the marks it makes in the sand are mesmerizing, a massive yet simple cooperation between human-made objects and natural forces.

The energy of the universe and earth, brought into view in the middle of an old power station; it is a fitting way to talk about nature within the space.

The work also makes visible intersections between art, science, and nature. As the artist, Marjolin Dijkman, explains, the work “relates to a moment in time when the arts, science and philosophy made up a connected field, open to exploration by amateurs and professionals alike.”

Several minutes go by and my friend and guide, Gianpaolo, remarks “I could stand here all day.” I agreed with the notion. My partner Suhee, however, had already wandered away to a giant trio of woolly monster sculptures fashioned from snow, desert, and forest camouflage .

The sculptures, collectively titled The Water, The Soil, The Jungle, were created by Müge Yilmaz, an artist from Istanbul, the sculptures are at once human and inhuman. For me, they offer a moment to contemplate that difficult-to-tread line of viewing ourselves as both part of nature, yet distinct from it.

On a lighter note, the sculptures honestly keep viewers guessing about whether they’re going to just start walking around. It’s ambiguous, whether they are animate or purely sculptural. Looking at passersby, the sculptures seem either to draw groups of selfie-snappers, or to be completely missed.

Well, they are camouflaged, after all.

Moving up to the second floor, we are greeted with an enormous, self-guided walkthrough installation called The Great Chain of Being—Planet Trilogy.

A sort of exhibition-within-an-exhibition, Planet Trilogy has the feeling of a film set on the surface of a desolate planet. Fittingly, it was envisioned by well-known theater director, Mou Sen. It’s eerie, dark, uncomfortable, and at the same time completely intriguing as we walk through multiple scenarios covering multiple floors, all of which are, at the very least, visually striking.

At best, the scenarios elicit some interesting questions about modern human culture, technology, and the complicated relationships that we hold with this technology. Rather than focusing on our past or current situations, the entire installation seems to elicit questions that hint at possible futures:

What does the future relationship of man, nature, and technology look like? Maybe it looks like a human body physically merged—and burdened with—our inventions, all of it being slowly reclaimed by moss.

What does it look like when humanity, devoid of ample resources on this earth, sets up camp on another planet? Perhaps it looks like an atrium dumped from space onto another planet’s surface, with plants inside struggling to come to terms with an alien atmosphere.

The futures considered here lean towards the dreary.

On the official program, this entire piece is credited to MouSen+MSG. As we exit the artwork back into the main gallery space, we find out that “MSG” is a program which Mou Sen established at the China Academy of Art and, furthermore, that the pieces within this giant theater set were produced by 40 artists, many of them students at the Academy. I am happily surprised by this. The number of thoughtful and well-executed pieces inside Planet Trilogy indicates a high level of thinking and skill mastery from the students.

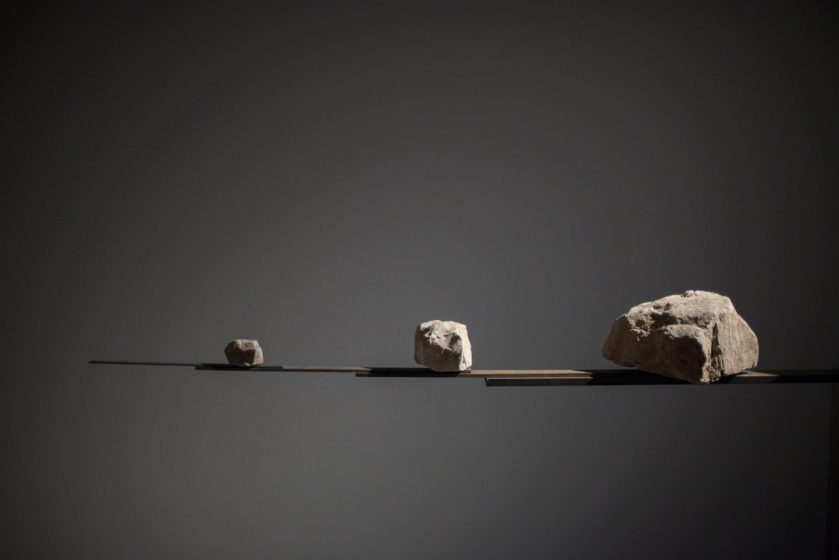

Two other works to catch my eye in the category of natural scenarios are Event and A Straight Line Extended, both works of Liao Fei. The first of these interrogates our scientific understanding of the universe, recreating an orbit with a mechanical arm, lightbulb dangling from the end. All of this moves along slowly through one of the main thoroughfares, revolving around a steel plate and a large stone. The circumference of the orbit is so large, and the movement of the contraption so slow, that it’s easy to miss what is going on. Indeed, quiet yelps and laughs are heard as the “sun” (the lightbulb) occasionally strikes unaware visitors on its slow and steady orbit through the gallery space.

The second of the works from this artist, Straight Line Extended, creates a gentle balancing act that wouldn’t be terribly out of place next to an Andy Goldsworthy piece; a simple, elegant display of natural elements and forces. It might not be the blockbuster of the show, but the worlk necessarily fulfills the mind’s need for playful wonderment, balancing out some of the heavy darkness of other works here, which, for my taste, are a few too many.

I enjoy standing with this one for a while.

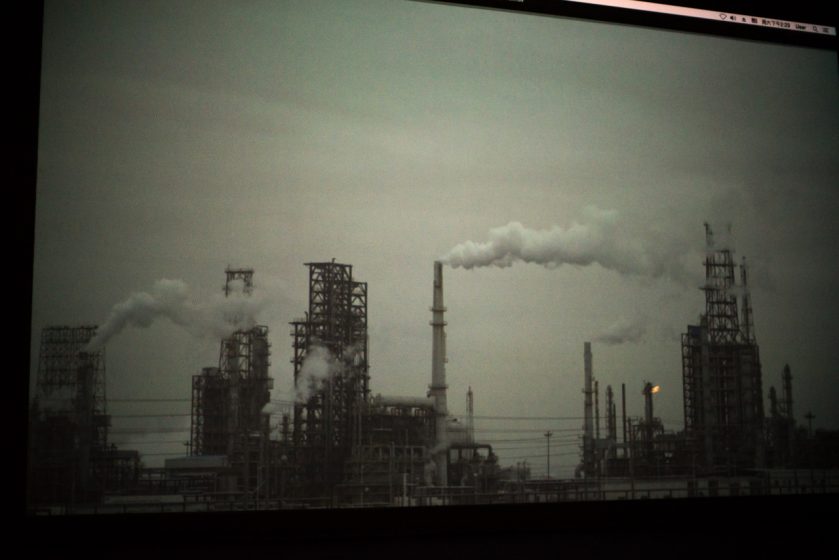

To return to heavy darkness, though, the film installation, Black Ocean, is tucked in the back corner of a 2nd floor hall, behind a giant curtain. Curiously, only two small benches adorn a space that could fit dozens, and though outside is bustling, few people sit down to see this one. I think to myself that perhaps the topic and geography it tackles—industrial resource extraction in the Gobi Desert—hits a bit too close to home for the institution, and perhaps for the audience as well.

The scenes that artist Liu Yujia presents in Black Ocean are of vast oil fields, open trenches, sandy, desolate, otherworldly looking settlements that are home to a vast resource extraction operation. She describes it as “a hallucinogenic phantom place.”

It’s certainly not easy to watch, especially because everyone sitting in the room likely knows what it means: these are the things that have to be done to this earth in order for us to be here at a giant art biennale, in a huge former power station, projectors running, bright lights shining away, climate control blasting, cars and taxis moving about outside.

The aforementioned “massive wall of concrete housing towers” flashes back into my mind.

Some leave the room immediately after coming in; very few others stay, glued to the screen, faces drab, gray, lifeless. Perhaps the reality check is too real for us; this is the cost of business—and art—as we know it today. I am pleasantly surprised, however, that the work, hidden as it is, made it into the bienniale at all, for it offers an abrupt and strong critique of an industrial world in which China, deservedly or not, is often painted in the worst light by international watchdogs.

Say what you will about censorship—it’s present here, as it is at some level in every corner of the art world—but the fact that such a critique is present in this kind of exhibition points, in many ways, to a maturity and openness we don’t normally associate with China.

If you manage to wander all three floors of the Power Station of Art in a day, you’ll be tired. Including artist teams and individual works not noted in the program, there are more than 140 artworks here from nearly as many artists—more visual and intellectual stimulation than a person can take in a single day. Unfortunately, I only have half of a day to see it all.

Although the jungle of works can be overwhelming, the curators of this exhibition, Raqs Media Collective, have certainly delivered a collection that pushes, and in some cases perhaps visibly moves, the boundaries of acceptable self-criticism in China.

They never push as hard as, say, Ai Weiwei’s Fuck Off exhibition, which famously ran in opposition to the 3rd Shanghai Biennale some 16 years ago. That exhibition was so controversial, it was eventually closed down by police.

But perhaps Why Not Ask Again pushes … just enough?

Patrick Lydon

San Jose & Seoul

Leave a Reply