West Asian countries Azerbaijan and Georgia recreate themselves and their cities in post-Soviet times.

We consciously and sub-consciously collect details and compare cities as we slowly make our way from Point A to Point B by foot. We have even created a mental game to pass the time during the many hours we are outside.

One version of the game is mentally listing and analyzing the things we perceived about cities in countries that have had a recent shared history but are now left to cast a new footprint in the world. Since we have spent many months walking in Central and West Asia, we often find ourselves stacking up cities that until the 1990s were under Soviet rule, and are now defining their new niche on the regional and global stage.

We started doing this last year when we passed through Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan and stayed for some time in the cities of Bishkek, Osh, Khorugh, Dushanbe, Bukhara, and Samarkand. We consider the look and feel of the cities now, imagine how they were before and guess what direction they are heading in. We notice things like architecture, infrastructure, housing construction, cars driven (a subjective wealth indicator on our list), popular shops, how people spend their time in the city and what products line market shelves (are they locally grown and made or imported?). From this, we make very subjective conclusions about whether the city is thriving or struggling in their new age, and whether we think it’s a livable place, at least in our heads.

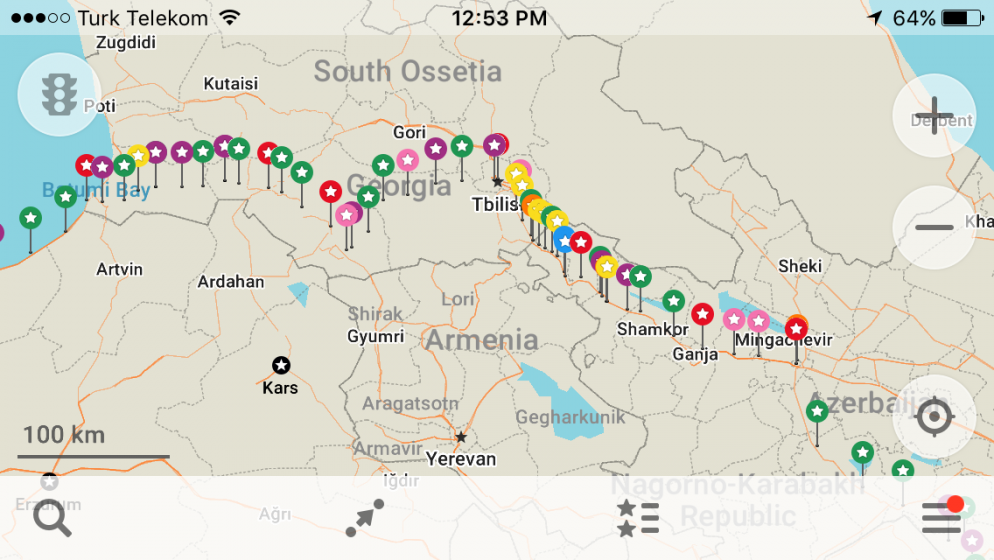

For more in the Bangkok to Barcelona series, click here.

Baku’s influence

Baku is a place where people come to be seen, party, shop, and stroll along the renovated waterfront promenade.

The Azerbaijan capital seems to have a new-found sense of itself, even if the urban zoning and planning elements look randomly assembled rather than thoughtfully and uniformly considered.

Baku’s post-Soviet personality is being built with oil and natural gas money, an image reinforced by the drills holing the dry earth around the Caspian Sea city and the number of tankers and trucks waiting to be loaded near its port. Modern buildings—the most famous of which are the flaming towers, which when lit, resemble flames of fire—are located a short walk away from historical sites and traditional houses.

Commercial centers and pedestrian areas lined with shops selling Western brands, trendy and crowded restaurants and cafes, expensive, luxury apartments with “For Sale” signs draped on balconies, and this “look at me” feel walking through city center rounds out the picture.

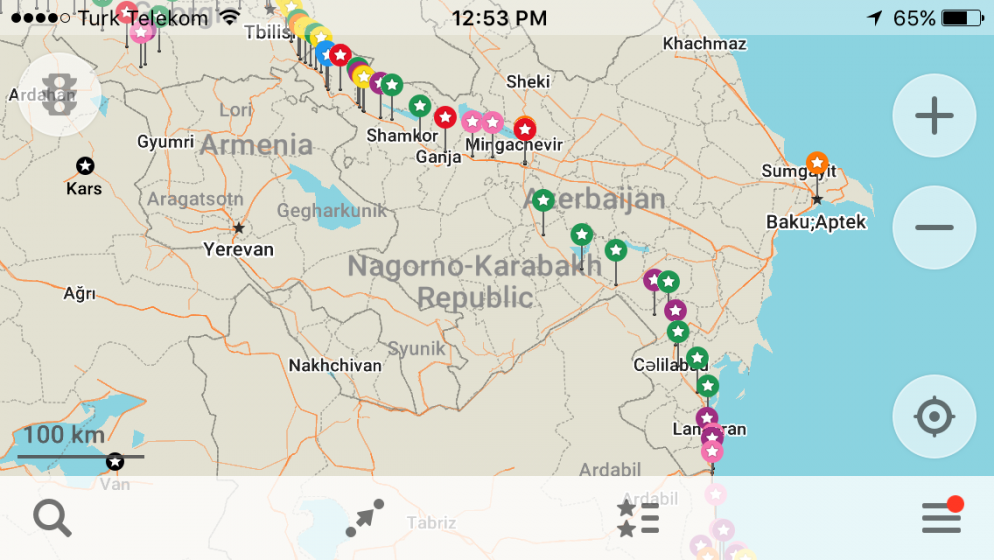

While the city is growing into its new shoes, so to say, and staking an economic claim in its ability to be strong trade partner with its regional neighbors (namely, Iran, Turkey, Russia, Georgia and Europe), Baku’s wealth, at least superficially, seems to trickle out to other cities along our walking route. *

The increasingly obvious movement of goods and money, along with the development of sea and land logistics infrastructure (including the construction of a cargo and passenger train line that will connect Baku with Tbilisi, Georgia, Kars, Turkey and eventually Istanbul, the doorway to Europe), touches other towns, like Ağstafa, Ganja, Lankaran and Yevlakh. These smaller urban hubs have refurbished their city center streets in a way that makes strolling easy. There are sidewalks and benches and conformity in the facades. Men, mostly retired men (never women), play backgammon for hours on patios of tea houses in nicely manicured parks. Drivers look for customers in high-end, second-hand Mercedes and Sprinter microbuses, and farmers use Russian Ladas, workhorse-types of cars common throughout former Soviet countries, to get from their homes to their fields.

Supermarkets have a broad display of products, written mostly in Russian letters, but also in Turkish, which is a cousin of Azerbaijan’s local language.

Although Azerbaijan is still less developed compared to its powerhouse neighbors and may be developing at a pace similar to Uzbekistan, in our walkers’ eyes, it seems to be faring better than, say, Georgia.

Georgia’s hope

Across the border in Georgia, another former Soviet country shaping its place in the 21st Century, a different scene plays out.

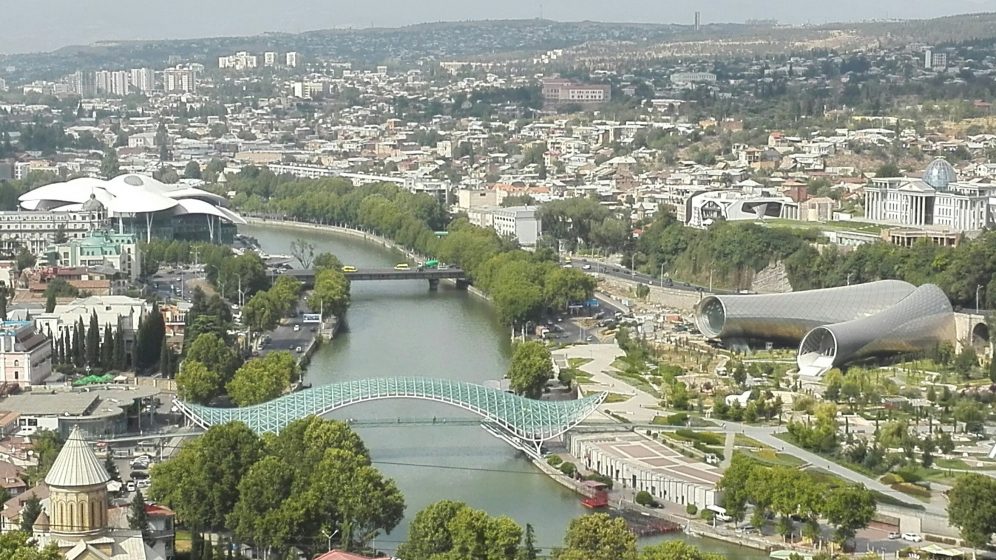

Tbilisi, the capital, feels like a place where legends and fairytales were born. Old bathhouses, churches, a fortress on a hill and riverside buildings embedded into the rock cliffs mark its history. Crumbling apartment buildings that would be condemned as uninhabitable in other places may initially come off as charming pieces time forgot, but, really, they are a reflection of the city’s challenge in levying affordable property taxes and securing local and foreign investment for development.

Bakeries selling hot bread from deep circular ovens and ladies selling fruits, flowers, and churchkhela (candle-shaped, local type of energy bar traditionally made from grape must, nuts and flour) are quaint Tbilisi features, instilling a romantic feel of age-old customs.

Although there are places in the old (and hyper touristic) part of the city and upscale neighborhoods where it’s easy to find Western amenities and brands, the number of second-hand shops, and the number of women inside them, gives me pause. The frequency of these shops, both in Tbilisi and in other cities we walked through, lead me to believe that locals have to manage their budgets, and opt for classic black pieces (black is the popular color for women of all ages in Tbilisi) that can be mixed and matched instead of spending their cash on fast fashion that eats away at the little extra they have at the end of the month.

There are, too, signs of shifting tastes. Tbilisi’s urban development leans towards catering to tourists and creating a European feel. A new park, the elegantly designed Bridge of Peace, trendy cafes and bars playing Russian and Western pop music, and upscale wine shops cover up scars from the civil war that started after the Soviet Union collapsed. Fenced in construction sites usher in the new hope of urban chic, and renovated, modernized apartments are being rented out on Airbnb, a common trend among Tbilisi’s citizens looking to profit from increased tourism.

Outside Tbilisi, we follow a route through the southern mountains. We simultaneously feel Georgia’s natural beauty and its isolation. There are long, stunning stretches of wheat and grass fields being cut and dried for livestock during the harsh winter, and farmers scurrying to pile up their old Soviet-style military trucks with as much hay as possible before the frost comes. Other rural stretches come with miles of barren, wind-swept nothingness. Small villages—with bare-shelved shops where locals buy basic goods like sunflower oil, biscuits, pasta and frozen chicken—are depressing with their abandoned, windowless houses, signs that locals have packed up and moved on.

Throughout Georgia, we walk with a feeling that most people are just getting by, and are struggling to accomplish that. Many Georgians have left the country, migrating to other parts of the world for economic security. And while politicians set their eyes on developing stronger relationships with the European Union, as witnessed by the EU flags flying on nearly every public building and police stations, Georgia’s West Asian geography and mountainous tough-to-mine exports of copper, gold and ferroalloys limits wealth distribution throughout its cities. It feels that way for weeks of walking… at least until we reach Batumi.

Batumi, Georgia’s important port and resort city on the Black Sea,* feels like a circus after the miles of quiet rural areas and small gray towns we passed.

Like Baku, which has a certain appeal for Iranians who are looking for a nearby, easy-visa place to party (many Iranian men told us they go to Baku to drink and dance at night clubs), Batumi attracts its share of Georgian, Russian and Turkish partiers. Its waterfront park, a good green space in its own right, is filled with clubs, bars and restaurants and kitsch tourist amenities catering to summer beachgoers; and for about 100 kilometers in Turkey, we saw billboards advertising Batumi’s luxury hotels, casinos and night life.

But, inside Batumi’s neighborhoods, where locals stroll, there is something subtle that makes the city livable.

There is a bustle that moves at a more relaxed, less heavy pace than Tbilisi. Whiffs of sea air catch us as we criss-cross city streets and parks, and there appears to be more investment in making the city a nice place to call home.

Still, though, locals want more.

“How do you like Batumi?” we ask a 20-something-year-old woman working in a fast food shop.

“It’s okay, but it’s too small for me,” she answers handing a customer an orange Fanta. “I want to live in a big city. I’m going to Russia…in Moscow, there is a lot to do”.

This is a sentiment we have heard in many former Soviet cities across Central and West Asia.

Young people, faced with limited job opportunities in their recovering and developing countries, want to go to Moscow, Istanbul, Berlin, New York, anywhere but where they are.

We walk on wondering who will stay behind to build whatever comes next for Baku, Tbilisi, Batumi, and all the cities in between.

* Baku and Batumi were not directly on our walking route. We took public transportation to visit them.

Jennifer Baljko

Bangkok to Barcelona on Foot

All photos by Jenn Baljko.

Baku, Azerbaijan

Baku’s development, which is being fueled by the oil and gas industry, has “look at me” feel. Its post Soviet style blends modern buildings, a recently built seaside promenade and restoration for old monuments.

Other cities in Azerbaijan

The wealth being generated in Baku, Azerbaijan’s capital, seems to trickle out to other main and smaller cities. Outside Baku, we found pretty main streets, modern buildings and parks where residents shade themselves on benches or play backgammon.

Tbilisi, Georgia

Tbilisi reminds us of legends and fairytales with its old castles, fortress and churches. New apartment buildings, that may be rented to tourists, are being constructed next to buildings that would be condemned in other places.

Other cities in Georgia

In rural areas, Georgia’s natural beauty captures our imaginations, but that doesn’t seem to be enough to keep the locals living there. Many cities in southern Georgia feel run-down, depressing, abandoned. Those that stay work the land or tend to livestock.

Batumi, Georgia

Like Baku, Batumi has a circus feel, a place where people from neighboring countries come to party on the beach. With that has come new development and renovations to parks, neighborhoods and shopping areas, all of which help make the city livable.

Leave a Reply