A review of Design for Good: A New Era of Architecture for Everyone by John Cary. 2017. 275 pages. ISBN 13: 978-1-61091-793-3 / ISBN 10: 1-61091-793-6. Island Press, Washington. Buy the book.

Throughout, the book identifies people who have made tremendous contributions, enabling success through their perseverance and selflessness. Such qualities can be emulated by everyone.

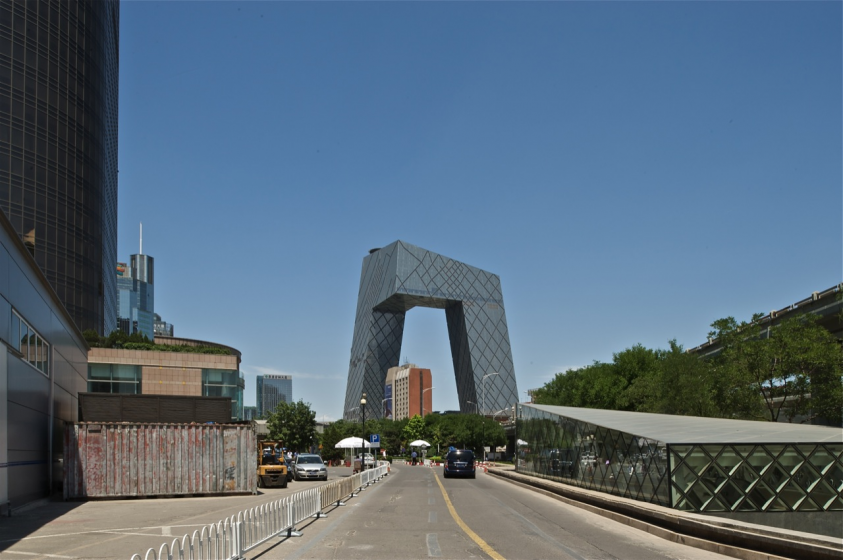

Along similar lines, we find today that architecture has become something that needs to be “marketable”—packaged, marketed, and then sold to consumers—thereby distancing itself from the very processes that we have always associated architecture with. These processes require designers to ideate through multiple scenarios that take into account social, ethical, and even political factors surrounding a project, and promote the want to effect change in the local environment and contribute to it positively. It is quite disheartening when the need to sell a project by means of an image gives rise to projects that are beautiful and exhilarating visually but are hollow and many times soulless in terms of their impact on their surrounding environment—both natural as well as built.

Along similar lines, we find today that architecture has become something that needs to be “marketable”—packaged, marketed, and then sold to consumers—thereby distancing itself from the very processes that we have always associated architecture with. These processes require designers to ideate through multiple scenarios that take into account social, ethical, and even political factors surrounding a project, and promote the want to effect change in the local environment and contribute to it positively. It is quite disheartening when the need to sell a project by means of an image gives rise to projects that are beautiful and exhilarating visually but are hollow and many times soulless in terms of their impact on their surrounding environment—both natural as well as built.

John Cary’s Design for Good comes at a time when it is so important to re-instill the hope that design brings to people—both designers as well as the people designed for. It sheds a ray of light into the design world by demonstrating how, through incorporating public dialogue and involvement, we can achieve end results that are hugely successful. If two young postgraduate aspirants from MIT have the drive and urge to explore beyond their comfort zones to eventually help communities in Rwanda—as did the MASS Design Group in the case of the Butaro Hospital project—then established professionals in the field can certainly take up the mantle and attempt to do the same.

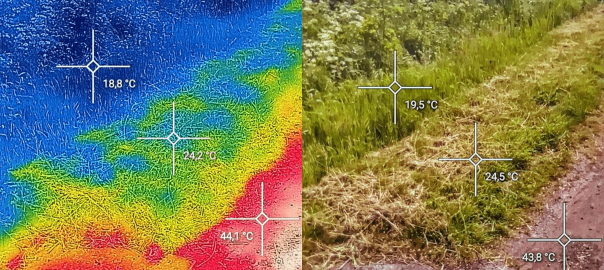

Whether it be the Angdong Health Center in China’s Hunan province, or the affordable housing Cottages at Hickory Crossing in Dallas, a place of worship such as the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka, or the Maternity Waiting Village in Malawi, Cary has carefully assembled an array of projects that are united in one simple ideology, dignity: dignity of the process, and dignity afforded to the people who it is designed for. “Human-centered design”, as Cary puts it, is the only real way for us to engage with projects from this day forward, focusing on the positive effects that can be achieved through the process and by finally building the project along with the community being deeply invested in it personally—physically in most cases and emotionally in almost all.

An important aspect that is consistent amongst projects that are successful at a community level is the larger network footprints that are generated around them. Public outreach and consultation is a prerequisite these days, featured as a part of the project brief put forth by almost every client for any type of project. This important and meaningful exercise of reaching out and receiving public opinion has in many ways been reduced to being a mundane task and very often is simply done because it is mandated. But some projects go beyond simply consulting the communities involved in order to achieve a greater level of integration. Take the example of the Women’s Opportunity Center in Kayonza, Rwanda. A vision of the Women for Women International NGO, founded in 1993, this project not only aimed to restore the integrity of women recovering from the country’s horrific civil war, but also looked to provide a continuing source of employment for them to rebuild their lives. We can no longer look at judging projects based on their individual design brilliance without considering the impact that a project has at a larger scale.

Urban design should not simply be left to the experts. Rather, it should become the responsibility of the promoters of every project as well as those who are involved in it, using basic studies such as impact assessment from an economic, social and cultural standpoint, not just at the neighborhood level but at a larger, city level as well. In the case of the Women’s Opportunity Center the eventual users of the institution were involved in many ways from the inception of the project. A brickmaking cooperative that was set up by Women for Women was already offering vocational skills and that system was scaled up. Women were trained in the process of brickmaking and participated actively in the decision-making of choosing earth blocks or fired bricks based on their strength and sustainability in the longer run. An astounding 500,000 bricks used for the building were made by the women who would eventually use the Center. The multifarious nature of the project also looked to go past stereotypes and break through cultural barriers that are seen in Kayonza. Despite there being a lot of construction activity in the town, women were never seen working on any site. As Karen Sherman of Women for Women said: “architecture and buildings such as this center are a means for achieving longer-term goals of women’s economic empowerment and income generation”.

As mentioned by Cary in his foreword, “human centered design” is a term that has gained a lot of traction in recent years, and one that raises an important question: “What is design if not human centered?” Reading through all the examples showcased in the book, this question keeps reappearing in the reader’s mind, and the realization with it, that once we realize the true potential of design, one cannot “unsee it”. This true power of design is ever more asserted when the processes of design are collaborative in all aspects, not simply to express good intentions, but to go beyond and explore the potential that is unlocked through the vast knowledge that locals have of their place and its resources.

I recently completed work on a documentary film titled Reading Architecture Practice: Mumbai, which I scripted and co-directed with two of my colleagues from the city. The film looks at the state of the practice of architecture through the various fields that architects engage in: design, pedagogy, research, conservation, and activism amongst others. Through interviews, different practitioners from the city were asked for their opinions. One common thought was the impending urgent need for collaboration within our cities. Prasad Shetty of CRIT emphasises what Salman Rushdie says—that living in a city is like watching a movie with one’s cheek pressed against the screen—all one can see are pixels. Similarly, there are others around you doing the same thing. To make sense of the movie as a whole, the only thing that can be done is to converse with one another, and figure out what the bigger picture is about. In my opinion, this really is one of the best analogies with regards life in cities, since it strongly propagates the ideas of participation and collaboration. Design for Good shouts out, through every page in the book, that collaboration is the only way a project can see success and be accepted into a community where it exists. Once collaboration is pursued, design decisions are molded by all those involved, invariably making the design process as well as the outcome truly “human centered”.

The book also lists various “fields” or types of design in an effort to qualitatively assess each project’s impact within its context (so does our film). It attempts to categorize the various ways in which design dignifies, in which design can be perceived, and the ways in which the potential of design should be explored. Design should not be a luxury reserved for a handful who can afford it. Rather, it is something that every person should demand and have rightful access to—a powerful resource especially when applied to some of our world’s challenges. Various impacts of design are encapsulated through the book such as design for all, for resilience, for stability, for security, for intention, for learning, for solidarity, for empowerment, for reclamation, for ritual, and for community, to name a few.

Categorizing projects based on the types of impacts they have is very successful in opening the reader’s mind to the true multi-disciplinary nature of design and its far-reaching consequences when applied sensitively to social conditions within our towns and cities. It is very important for us to break the stereotypes associated with the field of design, to go beyond what is understood as the pre-conceived limits of what a designer is responsible for, and to set new standards of engagement with the field. Design clearly does not start or end on the drawing board in the confines of offices—it begins when designers get to the ground realities and engage with people, convey design intentions, convince authorities for change, use local materials to ensure economic benefits to the community, build sensitively and ensure a sustainable model for future growth. Only then can we consider a design process complete in all aspects.

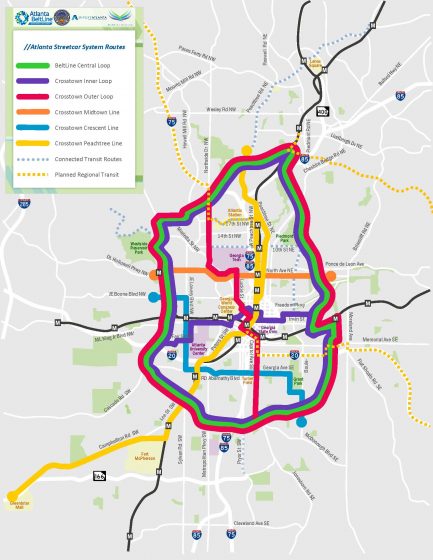

Speaking about the importance of multi-scalar impacts of projects within our urban environments, one of the standout examples documented in this book by John Cary is the Atlanta Belt Line project. What started out as a humble thesis project of a graduate student, became a shining ray of hope for the citizens of the heavily car-dependent Atlanta, supporting accessible walking, cycling, and the public park system. The defunct rail road system, which ran through a once busy industrial corridor, became an opportunity for improving public spaces and, at the same time, integrated the city across the “dividing line between communities”. Here is a case where, through active follow up and perseverance, Ryan Gravel, the brain behind the Belt Line, could persuade district council members to take up the project in their localities as an example for the rest of the districts in the city. Over 20 years of work, Atlanta now has several completed stretches that are used by thousands of people each day for walking, cycling, running, yoga, and other activities. All in all, the transformation of the Belt Line has enabled people to bring a qualitative change to their health and daily lifestyles. Such is the impact of a project that has been borne out of community efforts and implemented through political willingness and cooperation, which paves the way for other cities to analyze their future investments into multi-function public infrastructure.

Along with big investments, cities ought to focus their attention on community level initiatives as well. Easy access to smaller, decentralized public amenities always contributes to a better quality of life at the neighborhood level, thereby improving the condition of our cities in general. The local department store, a community hall, the small park and playground, an affordable school and hospital—these are the fundamental amenities upon which communities are sustained. The Bait Ur Rouf Mosque is Dhaka is a great example of a neighborhood amenity which is not only a place of worship and ritual, but also functions as a space to congregate for the community, and a place for education and learning for those who do not have access to schools. The design by Marina Tabassum plays a big role in creating an image of the community—not simply as a mosque, which is monumental and daunting in scale, but one which is approachable and warm. The humble use of materials and maximizing natural light and ventilation allow this mosque to become a beautiful neighborhood symbol even without typical features such as domes and minarets. The humility that Tabassum brings to the work echoes through this design and supports the core principles of the religion—coming together of people to celebrate a divine power, devoid of any irrelevant symbolism or ritual. Design, in this case, unifies.

Cary’s personal narratives and experiences of each of the projects and sites speaks of his in-depth knowledge. This engagement with projects across the world is, in many ways, another aspect of design thinking and pedagogy. Each example, in Design for Good is narrated more as an experience than as a mode of documentation. The author feels personally invested in each project, and that clearly shows in the way this book has been written. Cary is passionate about the quest for designs and designers that dignify, and his “call to expect more” at the end of the book stands testimony to his commitment to further design that is loaded with social, cultural, and physical impact. Cary manages to invoke within the reader an introspective thought towards projects that one has been associated with. It makes one raise questions that critically look at work through the lens of providing a qualitative benefit to the users. Did the project include a wide variety of user groups, execution teams, and participative owners? Did the project lead to affect any sort of positive change within the community in which it is located? Did the project aim to make the best of all available local resources—material and human? Did the project add dignity to its users and to the lives of those involved with it or affected by it?

Through every project, the book identifies individuals who have made tremendous contributions and have enabled the success of projects through their perseverance and selflessness—this is a quality that can be emulated in projects taken up by others. We should not sit back in our workplaces and wait for opportunities to land at our doorstep—we must define our larger commitments, and from there we need to be proactive, initiating dialogue and facilitating change in whatever ways we can. Design is a tool for use by all of us, let’s pick up the pieces, and move forward with this thought. Let’s empower, let’s dignify.

This book is a must read for all.

Samarth Das

Mumbai

On The Nature of Cities

To buy the book, click on the image below. Some of the proceeds return to TNOC.

Leave a Reply