The people living in Mumbai generally associate nullahs with dirt, filth, and odor. City authorities have channelized these waterways, building impervious concrete walls along their edges, thus further severing their ecological and environmental attributes, and separating them from the people. This must change. It is changing.

Madhav Gadgil, an eminent scientist and author of a landmark report on the conservation of the Western Ghats said in an interview, published in The Indian Express (another daily), that the scale of the disaster would have been smaller had the state government of Kerala and local authorities followed existing environmental laws. He further said that the problem was “man made”. “Unfortunately our state governments are in the grip of, and in collusion with, vested interests that do not want any environmental laws to be implemented, and the local communities to be empowered”. …“In terms of unregulated growth of illegal constructions, and creation of real estate all over, there are disturbing parallels (in Kerala) with Uttarakhand (another state in India)”. He said, …“These are not just natural events. There are unjustified human interventions in natural processes which need to be stopped”.

The understanding of nature, rather of every earth system, by most governments and their consideration in city-building endeavors is not considered important, rather deliberately ignored—submerged in the complexity of socio-political conditions that is often ridden with short-term material and financial gain. Tragically, this trend continues in spite of the devastation of land, property, loss of life and uncertainty of human existence caused due to climate change. It is people’s empowerment, participation and their movements for democratization of land and resources that would provide incredible possibilities, also being the most effective means, for the achievement of social and environmental justice.

The need for organizing participatory movements to check the ongoing destruction of natural systems and for achieving a sustainable ecology of cities is urgent and compelling. Re-envisioning cities through nature-based development plans and programs have become a priority. The Irla nullah reinvigoration movement in Mumbai is one such attempt and an example for bringing about structural changes in the way our governments conceive cities, prepare development plans and policies and undertake projects. Furthermore, this movement aspires to transform how Mumbai’s institutions approach open space and provide equitable access to ecosystem services for millions of people across the city, encompassing biophysical and social justice goals.

Mumbai is a city on the water with rich natural assets covering an area of 140km2 that define its geography. Sadly, the city has turned its back on such assets and considered these areas as dumping grounds, both physically and metaphorically. This has led to their degradation and environmental risk—such as flooding and pollution—that are threatening life and property. The central objective of this Irla movement is to revive and restore these natural assets and integrate them across the city, through participatory plans and programs, to achieve a sustainable and livable future for all.

This Irla initiative addresses the abuse and exclusion of over 300 km of watercourses, including four rivers within the city that have been turned into nullahs, or drains. These nullahs were originally natural watercourses, or rivers connected to the sea, thereby regulating ground water and assisting in dispersal of stormwater.

The people living in Mumbai generally associate nullahs with dirt, filth, and odor. Over the years there is little public knowledge of them being rivers and natural watercourses that defined the landscape. City authorities too have been apathetic towards the protection of both natural and open spaces, and have neglected their integration with the city’s Development Plan. They have channelized nullahs, building impervious concrete walls along their edges, thus further severing their ecological and environmental attributes, and separating them from the people.

This must change.

The Irla nullah movement

The Irla nullah movement was launched at the beginning of 2012 for the conservation, re-invigoration, and re-integration of a 7.5km nullah in Juhu, Mumbai. At the time, the Municipal authorities wondered why this was important. Battling such impediments, the movement continued: comprehensive plans and implementation programs were created through active citizen participation. Meetings were held in public places with posters and a Vision Juhu book, communicating the project. The gathered momentum could no longer be ignored by the city officials: the Municipal Commissioner finally approved the project eleven months later.

The central objective of the movement was to re-invigorate the nullah, including treating the waters and arresting silt formation. Although the nullah precinct and the neighborhood area contain vast number of public spaces, they are idiosyncratic, disconnected, and some are not open to the public. They are disparate in nature and function in isolation. These spaces include, the iconic Juhu beach, open spaces, gardens, parks, playgrounds, various public institutions like schools, colleges, training centers, music and dance schools, markets and health-care and community centers. There are over 20 such institutions along and in the precinct of the nullah.

These connected spaces could be further networked, as per the Vision Juhu plan, with neighborhood streets and marginal open spaces for integration and accessibility. The nullah itself physically weaves through the entire neighborhood as, potentially, a linear park, connecting various disparate spaces. Such networking of spaces realizes the high potential of networking different communities: fisher folk, slum-dwellers, hawkers, and all other classes. Almost 40% of the approximately 250,000 population of Juhu live adjacent to the nullah, while the remaining numbers reside within a 10-minute walk. Through this linear park, we could generate an active and pulsating system of public spaces, including the nullah that would form the spine of Juhu. This effort would continue to nourish community life, neighborhood engagements and participation, truly symbolizing our democratic aspirations.

Participation and the movementThe Irla nullah movement and the plan are conceived and executed through an active participatory process involving local citizens, elected representatives, officials of the government, celebrities, a host of educational and commercial institutions, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM), and certain state and national government agencies. An extensive public communications campaign backed by surveys and data, have led to wider participation in the project.

[Importantly, the movement and project exemplify the need for engaging multiple and diverse stakeholders in the people’s “Right to the City”, and their key role in scripting urban growth. To claim such a right is to assert peoples’ power over the ways in which our city spaces are created, with a determination to build socially and environmentally just and democratic cities. This requires systemic change in city institutions, and how the people participate in the democratic process. The challenges are significant, and include the conservation of a variety of vital natural assets; their integration with the urban landscape; and expanding public spaces (both physical and democratic). It is a model a paradigm shift in understanding Mumbai’s sustainable ecology and use nature-based solutions to improve, with equity, the quality of life for more Mumbaikers.]

Engaging people from all sections of our society continue to challenge such movements. It is largely the middle class who continues to control and lead this project. This is in spite of the widespread campaign by the proponents to involve all people, including the slum dwellers, fishing communities, business establishments, and the rich. As the project has evolved, only a few from the leadership of the poor have continued to participate, but others did not show up in large numbers. Probably projects such as these do not seem to be their priority or they do not see nor realize any short-term tangible benefit, caught in their daily struggle for survival. Addressing social conditions such as these and overcoming them requires much greater mobilization, public campaign for dissemination of information, enhancement of public knowledge on environmental matters and their integration.

Sadly, the understanding of many such significant public interest projects are considered to be a part of the many “beautification” works that certain sections of the upper and middle class propose constantly and consider as their contribution towards the making of a better city. Governments too have been proposing and encouraging many such projects in the city in order to divert peoples attention from more significant public interest works that are kept under wrap.

In keeping with the dominant upper and middle class desire for an exclusive and beautified city, most elected representatives have developed gardens and landscaping of traffic islands or medians along important roads where visibility is of prime concern, visible manifestation being necessary to win elections. While most elected representatives have supported public gardens and other beautification works, they seldom, perhaps never, proposed or actively supported policies and works relating to the ecology the city. Such indifference is the biggest barrier in the 300km of nullah re-invigoration.

Often, due to weak social and political engagements with diverse communities, various citizens’ demands and movements are termed elite. But this is dangerous, as often experienced, in the understanding of the larger ecological and environmental battle for the achievement of sustainable development. The destruction and degradation of the ecological conditions in Juhu and the city warrants various social and political movements to understand the impact this has on the poor and marginalized communities in particular. As a matter of fact, it is the marginalized people who suffer the most due to climate change impact that has been heightened due to the continuing abuse of the natural conditions. Urban floods is just one of the many threats that we experience.

Neighborhood-based development

The nullah and related projects serve a larger objective also. Both the Irla nullah plan and the Vision Juhu Plan, of which the Irla nullah project is part, demonstrate that through a neighborhood-based development approach it is possible to decentralize and localize projects, thus breaking away from monolithic planning and design ideas that are disconnected from most people (and often serve the interests of the few, not the many). “Master Plans” for cities are generally drafted by elite groups of designers, and fail to engage with citizens on their ideas. It is through neighborhood based projects that it is possible to maximize participation of the local area people and in that process achieve a greater sense of collective ownership. Importantly, it creates the opportunity for a more collaborative approach to city and place making, as clearly realized in this case. For citizens of Juhu, this project has allowed the immediate reclamation, redesign, and re-programming of public spaces.

The current mindset of formal planning exclusive to “experts” has to be challenged. Sustainable ecology and environment has to be the central aspect of city development plans, prepared with people’s participation right from its inception. It is with the objective of participatory planning that the rejuvenation and integration of the natural areas and the wider city is set out to be our mission.

A new geography

Projects such as the Irla nullah work can help us re-envision our city with streams of open spaces and water, thus defining a new geography. We can restore these nullahs to their past glory, and contribute towards the ecological regeneration of these natural assets. We can simultaneously break away from large monolithic spaces and geometric structures of parks and gardens into fluid stream of linear open spaces, meandering, modulating and negotiating varying city terrains. We can re-design nullahs to be linear parks, accessible to many people across various neighborhoods.

Considering citizens participation as the basis and strength of such ecology movements, the Irla project demonstrates the importance of neighborhood based planning and design for the preparation of the city’s development plans and projects. Considering neighborhoods as the basis for organizing movements for effective democratization of urban planning and design is key. Such an approach facilitates local people’s active participation in matters concerning their area, which they know best, while influencing the city’s planning and development decisions.

With the nullah and the public spaces being the main planning criteria, we hope to bring about, over period of time, social change: promoting collective culture and rooting out alienation and false sense of individual gratification promoted by the market. Our experience of neighborhood actions such as in Bandra, Juhu, and the Irla plan implementation in particular, has come to confirm that such initiatives can influence long-term change in the way development of the city is understood.

De-barricading the city and its unificationThere is a constant effort in carrying out public campaigns to explain the need for de-barricading the city and achieve unification, particularly its public spaces and the natural areas. This has been successful in the seafront projects in Bandra– another coastal suburb of the city, where spaces are open. In spite of the many significant social and environmental merits of the Irla movement and the project, the leadership there has gone ahead in proposing fences around the public parks and walls between the nullah and the adjoining gardens. Thus, public spaces, as much as the city, are yet again vulnerable to fragmentation and restrictions on free movement. They may have their reasons: vandals have abused and vandalized these places even during their construction.

Also, it is a constant struggle for achieving equality amongst the participants within a movement. Many significant movements that have been popular to start with have over time collapsed due to the hierarchical order within their organizations. Such social relations pose continuing challenge to the struggle for democratization of public spaces, indeed of the movements themselves.

To begin with, public campaigns as were undertaken by the Juhu residents’ movement to promote public dialogue and participation in decision-making would be necessary. Mapping of the area may follow this: documenting different conditions that exist, including the various changes that have taken place over time. People’s collaborative mapping of their own area is necessary in order to produce their own data and information that would, in most instances, differ with those that are constantly put up by the state. The issue is not limited to the production of people’s data, but evolving through that process their needs and demands pertaining to ecology, environment and development. The various studies conducted and the learning’s from the Irla movement is a telling story. The success of these efforts will hopefully propel people in different parts of the city to engage in similar movements.

Through this plan, we will generate an active and pulsating system of public spaces that would form the heart of Juhu. This will also provide a distinct identity to our neighborhood and all the people. Women, children, the aged, the young, will find opportunity to walk, cycle, play and intermingle. Groups, both formally and spontaneously, will be able to organize various social and cultural activity and get-togethers, including in the 500 capacity amphitheater built in a park adjoining the nullah, like music, dance, art festivals, and games for children, literary sessions and plays. The various schools and colleges in the area would be able to organize various students’ programmed too.

Keeping social, ecological and environmental values in place, the project has developed, with the active support of the Municipal Corporation, a forest of thousands of trees all along the first phase of the 1.5 kilometers of the nullah. This forest is a part of the larger idea of developing city-forests across neighborhoods and the city. Under this project the various forest parks that have been developed include the Kishore Kumar Baug (Kumar was a legendary Bollywood singer and actor), the Kaifi Azmi Udyan (Azmi was an eminent poet, writer and social activist) and a Children’s Forest Park. In the midst of these two parks a landmark amphitheater has been built that encourages spontaneous and formally organized cultural functions, named after Vijay Tendulkar (Tendulkar was an eminent theatre writer and director). In first phase, walking and cycling tracks and areas for children to play, pavilions for rest etc. have been developed. Good lighting and landscape have turned these places to be popular destinations. Thousands of people of all classes and communities throng these areas.

Building human resources

What this project has produced in terms of human resources is noteworthy. Through this project it has been possible to demystify and democratize the planning and design process. Citizens have actively interacted, and participated in various discussions and conferences, weekly site visits and interactions with the contractors, contributed to the formulation of design ideas and details, including the selection of materials and finishing’s. Many actively participated in the planning and design decisions from the inception. The myth of design and planning being the prerogative of trained professionals is, in more ways than one, dispelled through such collective efforts. The democratization of planning and design, and thereby of cities, has got a major thrust through this project. The mobilization of the collective to such an extent as in this project has successfully leveraged human resources at a neighborhood level. These citizens are now empowered to actively participate in decisions concerning planning and design of other projects of public interest in their area. This also reinforces the idea of participatory governance with the preparedness of an army of vigilant neighborhood residents taking ownership of their public assets.

These active citizens are now participating in meetings to discuss the forthcoming Development plan 2034 for Mumbai. Going beyond the interest of their area, they are prepared now to address matters across the city and build bridges with other citizens.

The key to the success of this pilot Irla project of addressing the issue of the watercourses of Mumbai has been the successful leveraging of all resources at a hyper-local, immediate and neighborhood scale. Residents of an area who feel strongly for their public assets can collectively assert pressure on government agencies for change; actively oppose disruptive forces to safeguard the larger interests of the environment as well as contribute towards the building of many more public assets, thereby leading to a mode of active and democratic development.

Collaboration and transparency

Fortunately, an earlier Juhu citizens’ movement for the restoration of the iconic Juhu beach and the experiences gained from it has forged for Irla nullah project important alliances and collaboration with many other neighborhoods and citywide citizens’ struggles. Such relationships generate enormous impetus to the localized movement, making it possible to sustain Irla and similar works in continuation and sustenance of initiatives in the future. As an example, Juhu citizens have participated along with other movements and projects through the form of Mumbai Nagrik Vikas Manch (Citizens Development Forum), in which over 20 citywide organizations have participated actively and engaged with several crucial city issues, like the ill-advised Coast Road, the elevated Metro and the opening of Aarey Colony, an eco-sensitive zone, for construction.

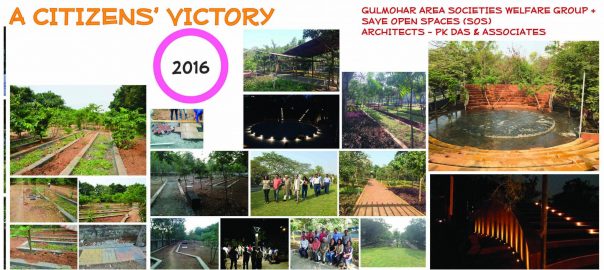

Collaboration and transparency are indeed the high point of Irla nullah. From the very inception of the plan, its execution has been possible due to the collaboration of multiple stakeholders at various levels. It is a unique story of teamwork. The list of collaborators includes the MCGM, which is the owner of the nullah and open spaces in its precinct; MHADA, the agency charged with the responsibility for its implementation; National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) which has provided designs for the water filtration and cleansing systems; PKDas & Associates architects supervised this project on an entirely pro bono basis; the Mumbai Waterfronts Centre along with Kamala Raheja College of Architecture (KRVIA) which jointly undertook the neighborhood study of Juhu, resulting in the Juhu Vision Plan along with its publication in 2006; final year architecture students from KRVIA who partook in a design studio exploring the redevelopment potential of the Irla nullah precinct in 2017; PUDDI that is currently taking further the study and primary research for the re-invigoration of all Mumbai’s watercourses; Gulmohar Area Societies Welfare Group, the citizens’ group that has spearheaded the daily supervision and vigilance of the project with the support of other local area residents associations: JVPD Housing Association, Juhu Scheme Residents Association, Juhu Residents Association, Rotary Club of Juhu, Gaothan (Village) Area Residents Association of Juhu, and Juhu Scheme Residents Association.

This movement has also seen participation of several individuals from the area that include Javed Akhtar, who’s MPLAD Funds not only financed the project, but whose active participation in contributions key decisions has lent a fresh perspective. It is also important to mention several designers who have contributed as consultants to PKDas & Associates on an entirely pro bono basis: Ganti Designs, for lighting, Enviro designers for landscape and SACPL, for structures.

The complexity of the logistics in establishing this extensive collaboration and carrying out the multiple tasks of planning and implementation on a entirely honorary basis is a testament to the transparency of the process, without which such collaborative efforts would collapse due to misgivings and communication gaps, which are common in such kinds of projects. The movement involved the publication of several booklets, public campaigns and exhibitions, round table discussions, public meetings, press coverage and constant liaison with various authorities and this effort helped to foster trust in the project.

Such processes as evident in the Irla movement highlight the dedication shown by all collaborators equally and these have not only contributed to the success of the project, but have also reinforced the values and importance of such endeavors for larger public interest works within our cities. The Irla nullah movement and the project has demonstrated the need and significance of participatory, collaborative and co-operative endeavors as the foundation for building a robust, resilient and sustainable city.

P.K. Das

Mumbai

with input from Darryl DeMonte and Samarth Das

Leave a Reply