The vision for the Carbon Landscape? “It would have to be a thriving place, a green place, a place for people, for wildlife, for recreation, for health, all of those things.”

Now thirteen partners spanning three different local authorities, local wildlife trusts, community groups, government agencies and universities are working together to give nature a helping hand, accelerating the restoration of habitats and creating connections not just between sites to create an ecological network, but between local people and the heritage of their landscape. The Carbon Landscape project is a five-year initiative funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

This initiative is taking an innovative approach to community engagement, drawing on the industrial heritage of the area to raise awareness about possible sustainable futures with the local community, organizations working in the area, and school children. This essay is a montage of many insights drawn from the decades of experience of the project partners that we interviewed in our research project. Many of them have been working and living in the region long enough to remember the coal mining and the vivid scars industrial exploitation left on the landscape.

“I remember someone coming up with the idea that carbon is that unifying factor between the industry and the habitat,” said one of the originators of the Carbon Landscape project. The project emerged from several years of multi-stakeholder and community discussions about how to look after this special landscape. While some people were deeply engaged with the area’s wetlands and the species that inhabited them, many others saw little of value in this place on their doorsteps. Those involved in outreach activities frequently mention how “it’s surprising how people who live very, very nearby don’t know anything about it.” If they do have any thoughts on the area, they are often negative, describing it as: empty, inaccessible, inhospitable, frightening, polluted, scarred, and industrial.

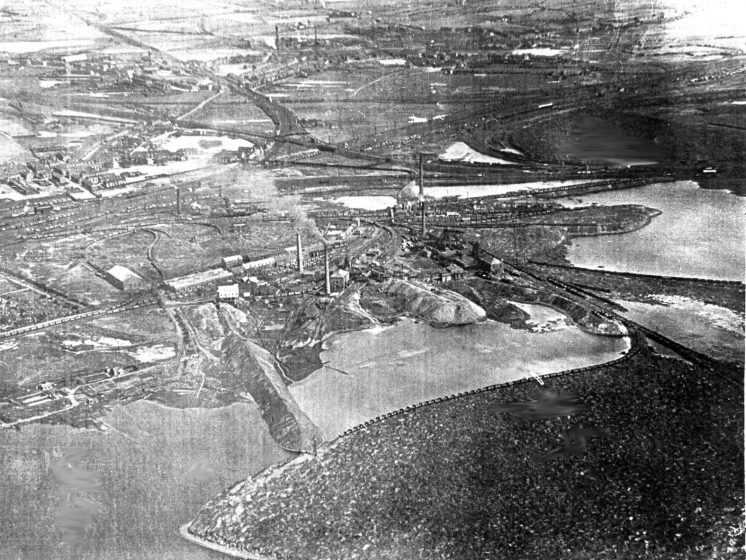

The current landscape is now unrecognizable as the coal dust covered and smoke-besmirched place that fueled the industrial revolution and corresponding urban development in North West England. The industry and associated jobs have gone, but the towns remain and strive to recreate local economies and improve the health and wellbeing of their populations. The surrounding renaturalizing landscape is an important resource in this endeavor. It provides nearby nature for about one million people and interesting opportunities for social and economic development. Many, however, still regard the open space on their doorsteps as a wasteland or a reminder of what has been lost in terms of secure jobs, strong communities and pride. The Carbon Landscape project is trying to shift the narrative to one that incorporates both nature and industrial heritage and sees these as assets and inspiration for a bright future, rather than a story of loss.

As another project partner describes, “I would say it was a landscape connected by carbon but carbon would mean different things for different parts of the landscape…it’s peat, and the carbon stored in that way, but as an ex-industrial landscape where carbon has been the driving force of that landscape for the last few hundred years, [there’s] a cultural heritage point of view from coalmining. So the carbon element ties current restoration work in the bogs and peatlands together with the historic aspects of coalmining in the region…But within that, a project that both tries to ensure that the landscape can adapt to future change, future climate change, and for nature conservation purposes, to facilitate species movement across the landscape, as species may need to move for climate change, in what is a quite fragmented landscape” in the only open area in this densely populated region lying between the urban conurbations of Manchester and Liverpool.

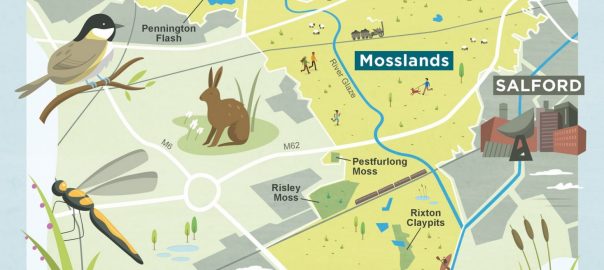

Even without climate change driven migration, this fragmented landscape needs reconnecting and this is an important aspect of the Carbon Landscape initiative. “We want to connect up islands of populations, we’ve got an island in one place, an island in another place and in between nothing at the moment. We want to try and fill the gaps in so that there’s ways the populations can mix,” says one project partner. Connecting up the different parts of the landscape in people’s perceptions is also an important part of the Carbon Landscape project.

The Carbon Landscape has three related but distinct landscape character areas: the Flashes (as the lakes formed by subsidence are known), the Mosslands with their peat soil, and the Mersey Wetlands Corridor bordering the Manchester Ship Canal which connected Manchester to the sea and facilitated its industrial growth—“and the factory is represented every time you go out, by the amount of strange alien weeds from America, that you find from the cotton industry, just growing in the pavement outside the building here.”

All of the areas provide habitat for internationally important species as well as significant recreational opportunities. The Mosslands are less accessible and considered less obviously attractive, as industrial scale peat extraction is only now drawing to a close, as a result of pressure from citizens and action on the part of local government. Peat extraction (for gardening use) along with drainage for agriculture has severely damaged and in many cases destroyed most of the lowland mosses in the UK, with only 3 percent of this habitat remaining, and not much of that in good condition. This has resulted in loss of habitat for a range of species, and other ecosystem services including carbon sequestration and flood mitigation. With interpretation and some access infrastructure, such as that available at Risley Moss, this 10,000-15,000 year old environment becomes an important and accessible recreational and educational resource. “It’s a fairly unique landscape I think, if we look at peatbogs, they tend to be very remote places in the middle of the countryside, in the middle of nowhere, it could be Scotland or the Peak District or the North Pennines. Whereas here, we’ve got that landscape but in a very densely populated area, …and actually, probably one of the most deprived areas in the country as well.”

With so many people living in and around the Carbon Landscape, its success depends on engagement of local communities and uptake of a different narrative about what the landscape means. Some people already have deep attachments to particular places and species, and have worked with others to protect these. There is a history of small groups of people being involved with looking after areas near where they live, often areas that may look quite ordinary to outsiders but where local people had noted the presence of particular species and characteristics. But for others it’s an unknown, and possibly frightening, place or a place with different meaning and uses.

“We sometimes forget in this industry that people don’t know about land biodiversity value, they don’t know about land ownership. If no one looks after it, it’s fair game, so they’ve adopted these landscape places as their own. Throughout generations they’ve gone up there, they’ve fished, they’ve used off road bikes, they’ve done shooting, they’ve just generally mucked around up there. That’s part of their individual story and heritage. For us to come in and take that away from them by putting up barriers without doing efficient community engagement gives a very damaging message in some cases. You have a love for the environment there, but it’s in the wrong perspective, it doesn’t align with our values. …My experience of doing community work is that kids…on nature reserves are seen as antisocial, so what everyone’s vision of what we’re trying to achieve is actually culturally not accepted anymore. If they’re mucking around on a nature reserve, it’s antisocial behavior (If they’re stuck on a computer, they’re ruining their future).”

Fear of antisocial behavior is a significant deterrent for many people in the area. They are wary of entering areas that appear uncontrolled or not looked after. Physical changes in the landscape may be needed to invite people in, as one project partner explained:

“At New Cut they put in this concrete tarmac path, and I was talking to some of the older people, they said, ‘we never used to come down here because we were scared, and now there’s a path and people are on their bikes and we don’t feel scared anymore, we can access this beautiful space’…it’s a change of cultural identity, I would say.”

While a perception of damaged communities in damaged landscapes brings with it many challenges, it also can be a motivator for engagement for some people.

“People get involved to do things if there’s a burning platform, if something’s broken, so one of the reasons we can be so successful with engagement right now is that people appreciate that this is broken, so there is a motivator for them to come out. Once we’re further down the line and things are starting to look good then you could argue that the motivation might drop, and I guess time will tell.”

Hopefully, as has been noted in other areas, seeing the positive results of their efforts will motivate engaged citizens to go further and hopefully attract others who needed to see that such work does make a difference.

Restoring pride is a key element in driving engagement with the landscape. As a project partner points out: “A lot of these communities have had a bad time in the past in terms of all sorts of issues. So it’s about pride in communities and there’s a lot of that going on in Manchester in different places, restoring pride in communities that have had a bad time. And the nature bits should be part of that as well, of restoring local pride.” Another says, “There are communities like ex-mining communities or agricultural communities in places like Irlam and Wigan where there’s real pride in that history and people maybe don’t still connect it with the landscape itself and that, that could be used to really benefit people in terms of having a sense of place of where they live and feeling proud about it.”

Linking this pride to the landscape can be an entry point for a better understanding of it. “I always say, do you know about these internationally important wetlands, we’ve got some species that are as rare as pandas, this is talking at a kids’ level, people connect to that, people like the thought of having super rare wildlife. It’s because it’s this post-industrial landscape that you won’t get these anywhere…this is unique round here and people like that story.”

People learn about what is special about this landscape through simple activities, as one project partner explains: “They didn’t appreciate how much was on those sites, and it was just a wasteland behind where they lived, and by going out and doing events like bioblitzes, walks, we slowly started to change some of those attitudes into there’s more here.” It is also important to start from people’s interests, which is facilitated by having multiple partners connected to different interests and groups of people (local communities, groups interested in cultural history, in protecting species and their habitats, in restoring waterways, etc.).

“You’ve got people who were already interested in recording wildlife and doing it that are now wanting to know more about what is the Carbon Landscape, why is that more important than somewhere else? What is the Greater Manchester Wetlands [of which the Carbon Landscape is part]? It spurs those kinds of conversations. And then the flip side of that, the community guys, they’re telling people the story and then they want to get involved. How can they get involved? There’s these opportunities to start recording, and that helps to write the story going forward.”

“Starting to give that landscape scale picture [is important] as well. It’s not just this site, it’s how that links to the next site, and how that links to the next site.” Seeing the bigger picture helps people to understand that their efforts are part of something larger and impactful, which is an important source of motivation. But it can also be a challenge to get people beyond their local area. “We’ve had many attempts at getting the volunteers to be landscape scale volunteers, and it hasn’t worked yet, and I don’t know if it works elsewhere in the world, but the people from Woolston love Woolston, that’s why they’re volunteering, the people from Wigan Flashes love Wigan Flashes, that’s why they volunteer, et cetera, and the people from Wigan Flashes don’t want to go to Woolston any more than the people from Woolston want to go to Wigan Flashes, because if they’ve got some work to do [at their site], well it’s their volunteering time, they want to be there.”

It’s also difficult because people are often unfamiliar with the other areas of the Carbon Landscape. Greater access, connectivity and interpretation are needed to facilitate their engagement with it. The proposed Carbon Trail and Carbon Loops are seen as key vehicles for this. “One of the things I’m really looking forward to, to actually promote this as a landscape are the Carbon Trail and the Carbon Loops. I’m looking forward to those being in place so that I can advertise them as a Carbon Trail, and it’s the Carbon Landscape and this is the Carbon Landscape story. I know they’re still under development. I’m looking forward to cycling those myself so I can see how the different habitats and spaces blend as you move from the south up into the north.” This contact is expected to lead to engagement, “you’re opening it up and people are seeing things that they’ve not seen before, that makes people care about stuff.”

The Carbon Trail will connect gateway sites with the different areas of the Carbon Landscape. There will also be several interpretive walking trails, ‘Carbon Loops’ that will tell the stories of the different character areas, including a story of sustainability that illustrates what has occurred in this landscape in the past and how it can be transformed in a more sustainable future. These will be based on the RoundView, a way of navigating towards a sustainable future that is being used in community and school workshops in the Carbon Landscape to link our modern understanding of the environmental problems unleashed by the industrial revolution to an inspiring vision for the future, where human activities fit well within the landscape. The RoundView traces the long history of the landscape from the formation of peat and coal through the industrial revolution. It conveys that all of these events, and particularly the anthropogenic effects, are very recent chapters in the history of the planet. It describes how the process of change continues, and with it the opportunity for humans to do things differently in the future.

The Carbon Trail will bring people into the landscape so that they begin to know, use and care for it, and it will also establish connections among the surrounding towns by linking up and signposting active travel corridors. But some partners are concerned about conflicts between access and connectivity for people and for wildlife: “I would love to see proper links in the landscape being developed. Proper wildlife corridors, so that the landscape is working for wildlife. A by-product of that in my world, but equally valid, is that if it’s working for wildlife, it’s probably working for people. Because porosity is porosity. The only problem I have, is as soon as I mention the word, green corridor, somebody says, you can put a cycleway along that, and I instantly lose my green corridor. So, that’s why I separate the two to some extent, my green corridor is primarily the way that hedgehogs, newts, willow tits move through the landscape. Its secondary function in my world, is as an access for people.”

This discussion about the Carbon Trail and connectivity surface a dynamic tension in the Carbon Landscape project, that of balancing protection of nature and access for people. Some people argue that unless people get into this landscape and care about it, it won’t be protected for other species. A lot of the land is privately owned, demands for housing are very high, new economic opportunities are much needed. There is a tension between conservation and development to improve access and also to provide a funding mechanism to finance restoration work, through for example building new homes on the edges of the mosslands.

Discussing the intense pressure for development in the peri-urban landscape, one project partner said: “At the end of the day, if we want to achieve our goal, we have to engage local people, we have to engage people from further afield. We have to make these sites accessible. They are urban, so we have to create a relationship between people and biodiversity.”

“It’s about ensuring, from a sustainability point of view, that the landscape is treasured for its original assets, its natural assets and what that has provided for us, but it continues to evolve to meet the needs of future society, so that they then continue to value it.”

As the Carbon Landscape acts as an illustration of this history of change, including destructive changes, so can it act as a demonstration landscape for different practices that work for both people and nature. Opportunities for more sustainable livelihoods are emerging, including those related to heritage/eco-tourism and sustainable agriculture. The narrative of this region also includes innovation, and that element too can be called up in support of sustainable transitions. “This area used to be the most innovative region in the industrial revolution. We were frontline of technology and the way people were living their lives and thinking. It’s been overtaken now by modern life, but we have an opportunity again to grab that innovation and lead the way to create a green corridor and more sustainable way of living, a happier, healthier community…focusing on the innovation and wanting to change what connects people with their environment…I feel like a story of our site is about innovation into nature.”

The vision for the Carbon Landscape? “It would have to be a place that was a thriving place, a green place, a place for people, for wildlife, for recreation, for health, all of those things.” Through innovative community engagement, active volunteering and working with partners and cities to improve our scientific knowledge of restoration of post-industrial landscapes, the Carbon Landscape project aims to inspire a step-change in the landscape and to bring hope for a sustainable future.

Janice Astbury and Joanne Tippett

Manchester

Many thanks to participants from Cheshire Wildlife Trust, City of Trees, Environment Agency, Greater Manchester Ecology Unit, Inspiring healthy lifestyles, Lancashire Mining Museum, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester Museum, Mersey Rivers Trust, Natural England, Peel Land and Property, Salford Council, The University of Manchester, Warrington Council, Wigan Council, Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester & North Merseyside and Woolston Eyes Conservation Group.

Rererences

Carbon Landscape Partnership (2016). The Carbon Landscape. Landscape conservation action plan part 1. Preston: The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Greater Manchester & North Merseyside.

Great Manchester Wetland Partnership Technical Group (2014). The Carbon Landscape interpretation Report, 28 May 2014.

Tippett, J. & How, F. (2018). “The SHAPE of Effective Climate Change Communication: Taking a RoundView.” In W. Leal Filho et al. (Eds.), Handbook of Climate Change Communication: Vol. 2: Practice of Climate Change Communication, 357–72. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70066-3_23.

Tippett, J., Farnsworth, V., How, F., Le Roux, E., Mann, P. & Sherriff, G. (2010). Learning to embed sustainability skills and knowledge in the workplace. Manchester: Sustainable Consumption Institute. http://www.roundview.org/background/research/

about the writer

Joanne Tippett

Dr Joanne Tippett is a lecturer in Spatial Planning in the School of Environment and Development at the University of Manchester. Action research funded by the Sustainable Consumption Institute and 250 staff in Tesco led to the creation of the RoundView Tool for Sustainability [www.roundview.org].

Leave a Reply