Whereas biophilia is a popular meme for urban and ecological design, rarely is biophobia addressed. Perhaps it’s easier to pretend the “undesirables” don’t exist, but that’s just not realistic. The “crows of Vancouver” posed a reality check on the consistency of my narrative.

Metro Vancouver’s twice daily crow migration is a sight to behold. Check out this short video for the dynamism

Prior to human settlement, Northwestern crows (Corvus caurinus) in the Pacific North-West were mainly limited to coastlines where they enjoyed seafood, in particular whelks (Thais lamellosa). Their adaptable use of tools and high degree of intelligence was noted by a study that observed their feeding behaviour (selecting prey, then deciding how and where to drop the whelks to crack their shells), (Zach, 1978). Their talent of facial recognition is known by anyone who has purposefully disturbed a nest or a colony. In the meantime, the emotional and social intelligence of crows has been revealed through neuroscience conducted by the Marzluff lab at the University of Washington.

Further to the conditions of our cities, the ability of these birds to thrive in our cities is enhanced by their culture of social behaviour, generational learning, and cognitive sophistication. As with other species that are long-lived and congregate as flocks, and especially given their large brains relative to body size, crows are intelligent and adaptable because of their high behavioural variability. This faculty not only equips them for survival, but allows them to evolve within a single generation via social learning and the development of traditions to avoid random extinctions (Marzluff, 2014). This helps explain why crow roosts across urban North America have grown so large: they’re super smart and socially resilient!

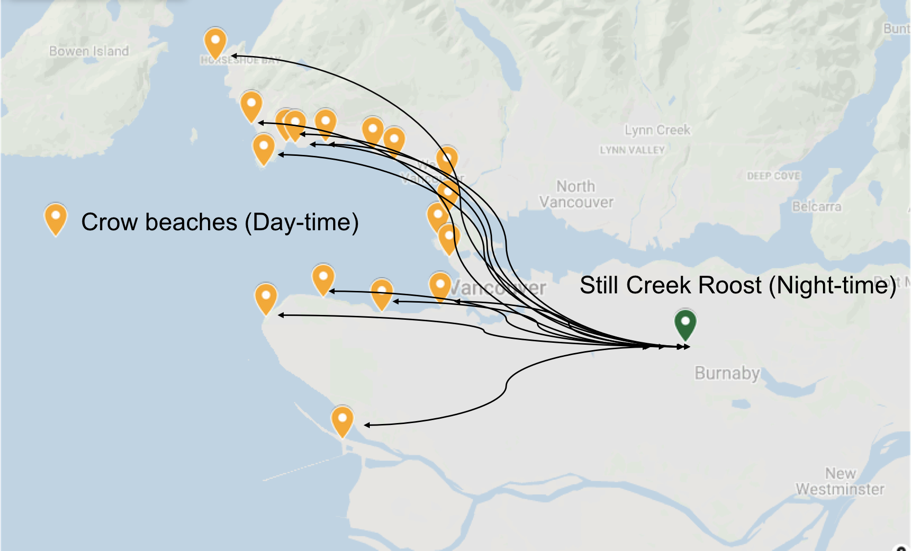

Among the categorisations of urban bird responses as defined by Blair (1996), crows are exploiters. This means that they thrive in our presence. Like other classic exploiters (e.g., the “fab five” that live in nearly every city in the world: house sparrows, European starlings, mallards, Canada geese and rock pigeons), crows live around our homes, eat our waste, walk our streets, and are among our most familiar birds. Not surprisingly, then, the crow population has grown in concert with human activity. Urbanisation and agriculture transformed forested areas into open landscapes, which provide scrubby areas favoured for roosting and an abundance of food. While crows still like to spend their days foraging at the beach (who wouldn’t?), they sleep together in large roosts at inland sites with favourable microclimates.

In Vancouver and the surrounding region, i.e., the Lower Mainland, the Still Creek roost is the bedroom community for all crows. At its peak in the winter, when nesting and mating is but a glimmer in a bird’s eye, the congregation of crows at Still Creek includes adults and juveniles together. In winter 2019, it was estimated at 20,000 birds. Such a large and singular winter congregation is a relatively recent occurrence, apparently, and likely the product of different parameters, like large-scale habitat loss, predator protection, and urban food resources.

The scene

Motorists and fast-paced pedestrian urbanites may be oblivious to the endless river of boisterous black birds moving through the sky above, but when you find yourself in the middle of “crow hour” your senses are so overwhelmed that oblivion is a felt experience. In addition to the sensory overload, it is unsettling to be a minority life form surrounded by thousands of intelligent birds.

The setting in which I experience this phenomenon is on the main campus of the British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT), east of Vancouver in Burnaby, BC. After arriving from their respective day territories, but before bedding down at nearby Still Creek, thousands of crows descend onto BCIT campus in what can only be described as a party. The cacophony deafens the frequency of traffic and planes. Every surface is covered: roofs, parking lots, trees, power lines, lawns, tennis courts, playing fields, paths, etc. Awe overpowers all other emotions, and few can resist stopping and taking photos. This is crow time.

As an urban ecologist, researcher, designer and advocate of green roofs for biodiversity and ecological landscapes, I have been challenged by these birds since coming to BCIT. On the one hand, the crows have created excessive work for me, sometimes drawing tears of frustration. On the other hand, and more disturbingly, the crows have forced me to acknowledge mental states that do not align with my values – aversion, resentment and biophobia– while fundamentally challenging my philosophy of biophilic design. When I realised that most discussion about urban birds refers predominantly to desirable birds (which we want more of), and that most discussions about “nuisance” birds are relegated to commercial enterprises (specialised in keeping them at bay), I felt like I’d touched a nerve.

The challenge

Over two glorious days in November, a crew of volunteers helped to plant BCIT’s newest green roof experiment on the Elevated Lab. Following a pre-randomised experimental design, 4,800 plugs and bulbs were planted into designated spaces across 240 (1m2) plots. It was a lot of work to ensure that the plants were placed as specified by the design. We finished at dusk on the second day, and I was ecstatic and exhausted in equal parts. The autumn rains could begin!

My blissful state of accomplishment was soon replaced by despair and horror, however, as the crows systematically undid our work every day. For several hours each week, I was on the roof re-planting the damage. I had hoped for the best—that the crows would regard the planting with interest and move along—and now realised how meagre “hope” can be. In the months prior, I had in fact toyed with setting up some form of bird protection, but we hadn’t budgeted for this and I dislike bird netting (which seemed like the only option). The regret was tearful and exhausting. The sound and just the thought of crows issued a rush of anxiety in me. It felt unhealthy.

However wearisome the re-planting was, I was most challenged by the experience of coming up against the limit of my feel-good narrative about green roofs and urban ecology. On the one hand, I continued to sing the familiar mantra that “green roofs provide habitat for insects and birds” but now sensed the arising of an exclusion clause: “…except for crows”. I was confronted with a major flaw in my narrative, and one that felt hypocritical and skewed.

What to do?

The outcome

After some reflection and discussion, the issue became clear. I don’t have anything against crows. Rather than anxiety and loathing, disempowerment and resentment, deep down I wanted to celebrate them with admiration, interest, and affection! With regards to the project, I needed the plants to establish successfully. Knowing their abilities of facial recognition, I definitely don’t want the crows to recognise me as an adversary. As it stands, they probably regard me as “crazy woman who waves arms at the sky begging for something called mercy”. I needed to figure out how to reconcile with the birds, at least for the establishment period, and definitely wanted to avoid becoming a dive-bomb target.I consulted with colleagues from BCITs Ecological Restoration program and from the green roof industry, and investigated more seriously into the range of available bird deterrent systems. Crows are highly intelligent and can figure out most scare tactics in a matter of days, which is why scarecrows or stationary owls don’t work.

I decided to invest in a non-lethal,multi-sensory bird deterrent system,in order to discourage crows from loitering around the green roof. This integrated management program uses pyrotechnics and amplified recorded sound on a randomised program, and has been shown to successfully disperse crow roosts, and reduce the appeal of a location. Apparently birds have a strong aversion to lasers, and the type used is similar to the seasonal projection lights that were popular during the festive season. The amplified sound system features calls that make birds uneasy; these include the call of a predatory bird (peregrine falcon) and distress calls by ravens and crows. Taken together, this multi-sensory system should make this area of BCIT campus less attractive for birds, keeping them on edge. We set the timer for dawn and dusk, and a couple random times during the day.

Bird damage after installing the deterrent system was significantly reduced, but not entirely. Given the scale of the population, however, perhaps this is as good as it gets.

The bird conflict on the Elevated Lab was a test of co-existence and a poignant invitation to explore the tensions between love and respect for self and for “other”; that is, respect for the project and for my well-being, and respect for the birds. It was fascinating from a philosophical perspective, as it put me in touch with what feels like a fault or a crack in the bedrock between biophilia and biophobia. Whereas biophilia (“love of life”) is a popular meme for urban and ecological design, biophobia is rarely addressed. Perhaps it’s easier to pretend the ‘undesirables’ don’t exist, but that’s not realistic (and it would be a serious oversight for those who are designing for urban wildlife!).

This situation also got me thinking about how we humans tend to hate successful species that we consider unwanted or undesired. Whether we refer to them as weeds or volunteers, the duality of judgement remains. The irony, of course, is that when we try to eradicate species that we feel are problematic, we may end up creating even more and better conditions for them through the disturbance. The fact is that the urban species most familiar to us are reflecting us back to ourselves: their presence is a direct result of our presence. In this light, reactive hatred for “other” implies self-hatred, too, via our unaware subconscious.

As if to reinforce this hunch, I’ve since learned that cultural responses between people and crows are reciprocal. Marzluff (2014) suggests that we can play a meaningful role in such cyclical cultural phenomena, which means we have a choice in whether we want a human-crow culture that manifests expressions of conservation and care, or otherwise. For example, when birds like corvids are rare, humans either ignore or revere them; but when they become competitors, humans tend to view them as pests. Whether they are persecuted or revered, intelligent birds like crows and ravens will respond with behaviour that accords with the prevalent human attitude. The choice is ours.

My winter crow saga was beautifully closed off with the 8thannual Crow Roost Twilight Bike Ride, curated by the Still Moon Arts Society in East Vancouver. This group ride follows the evening migration along the Central Valley Greenway (parallel to Grandview Highway mentioned earlier), right to the heart of the Still Creek roost. The event attracted about 30 cyclists, and you could pick out the seasoned participants by their crow costumes and range of caws. The organisers introduced this year’s ride with emphasis on respect and acknowledgement for the crows, their culture and territory. This meant that when the ride arrived at the roost, all bike lights were turned off and a quiet respectful atmosphere was maintained. The birds did not fly off in agitation as they had the year before, and for those sensitive to perceive it, perhaps a culture of restoration had been established.

My experience with Vancouver’s crows this winter issued a strong reality check on my narrative with regards to urban wildlife and green roof ecology. I’m grateful to the crows for showing me the middle path between the extremes of love and aversion, such that I can appreciate them for what they are, accept what they represent, and receive what they have to teach. In this era of biodiversity loss and the rising consequences of an over-engineered world our most common species represent an opportunity to reconnect with the dwindling wildness of the Anthropocene. I acknowledge that I have personal agency on viewing my world as alive and beautiful, just as it is, inhabited by the people and species who are my neighbours. As the crows start to nest down, I am now looking for my local corvid families to befriend.

Christine Thuring

Vancouver

References

Blair, RB. 1996. Land use and avian species diversity along an urban gradient. Ecological Applications 6:506-519.

Marzluff, JM. 2014. Welcome to Subirdia: Sharing our neighbourhoods with wrens, robins, woodpeckers, and other wildlife. Yale University Press. New Haven.

Marzluff, JM and KN Swift. 2017. Connecting animal and human cognition to conservation. Behavioural Sciences. 16:87-92.

Zach, R. 1978. Selection and Dropping of Whelks By Northwestern Crows. Behaviour 67(1-2). https://doi.org/10.1163/156853978X00297

Leave a Reply