We have been working on a new book of global short (flash) fiction on future cities. Here it is: A Flash of Silver Green

Very diverse in form, these 1,200 stories included science fiction, magical realism, speculative fiction, and fantasy. After many rounds of judging, fifty-seven of these stories from 21 countries were compiled into a book titled A Flash of Silver-Green: Stories of The Nature of Cities. Seven of those were judged to be prize-winners, authored by women from the United States, Canada, and India.

To place these stories in context, literary scholar Ursula K. Heise was asked to write an introduction that offers a cultural backdrop to work that tackles the future of cities from an environmental perspective. Her full introduction is included below, and the collection of stories can be purchased now from Publication Studio.

David Maddox, Executive Director, The Nature of Cities

Curtis Walker, Production Coordinator, PS Guelph

Malerie Lovejoy, Co-Editor, A Flash of Silver-Green

* * *

Floating cities. Flying cities. Domed cities. Drowned cities. Cities that flip over once a day to expose different populations to sunlight. Cities underground, in the oceans, or in orbit. Cities on moons, asteroids, or other planets. Cities of memory, of surveillance, or of violence. Speculative fiction in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has offered an enormous range of urban visions of the future, many of them dystopian, a few utopian, and quite a few somewhere in between.

For good reason: Cities have taken on a new centrality for human futures. In 2008, the World Health Organization and the United Nations published data showing that more than fifty percent of humans now live in cities, for the first time in the history of our species. By 2050, this figure is expected to rise to seventy percent globally. Much of this increase in urban populations will occur in Africa and Asia, often in cities that are not—or not yet—well-known globally. Some ecologists and demographers argue that this shift in where people live will be one of the crucial environmental challenges of the twenty-first century. Where earlier generations of environmentalists had worried about population increase as a problem in and of itself, these researchers shift the focus from the sheer number of people who will inhabit Earth to the kinds of habitats that will be built to house and employ them and to provide them with infrastructures of water, food, energy, health, education, justice, and governance. Since the new cities that will house twenty-first century people are only beginning to be built in many parts of the world, they offer enormous possibilities for constructing sustainable, healthy, and enjoyable places. But the social and ecological challenge is that many will be constructed informally, without the guidance of laws or building codes (or in defiance of regulations), let alone the input of urban planners, architects, or landscape designers—and even with such guidance, sustainability in fast-growing cities is of course far from assured.

The explosive growth in cities over the next century will entail far-reaching political, economic, social, and cultural consequences. And it will unfold in the context of ecological risks that range from local to regional and global scales: from soil, air, and water pollution to altered water and energy regimes, biodiversity loss, and climate change with its increased threats of droughts, floods, fires, and sea level rise. Many cities in the global South as well as the global North are already struggling to address these challenges—sometimes as a matter of sheer survival, sometimes as a matter of health and social justice, and sometimes as a matter of improved urban livability and aesthetics. Many new paradigms and concepts in urban ecology, urban planning, architecture, landscape architecture, design, and environmental activism have developed to engage with these issues over the last thirty years: ecological urbanism, urban political ecology, urban metabolism, urban environmental justice, biophilic design, and climate urbanism, to name just a few, have transformed the theory and to some extent the practice in these fields of research and activism.

Translating such principles and ideas into reality often requires a vision of the future of cities in the face of global ecological change. Between the promise of more livable and sustainable cities and the threat of a “planet of slums”, as the geographer Mike Davis has called it, artists, architects, and writers have frequently sought to outline such visions over the last half-century. From the Japanese Metabolism movement in architecture in the 1960s to the recent advocacy for biophilic design in the United States, architects have incorporated the forms and functions of organisms and biological structures into their building models. New Urbanists have developed principles for more walkable cities with a greater number of parks and green spaces. Designs for green roofs, vertical gardens, and urban farming are seeking to bring back some of the practices and products of nature that were driven out of the city during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Conscious of the global crisis in biodiversity, environmental activists are reintroducing native plants into city centers and educating urban dwellers to use their backyard spaces for the creation of wildlife habitat. Some geographers and anthropologists are even calling for a new “zoöpolis”, cities designed with the awareness that urban spaces are not just inhabited by one species—humans—but by many other species as well. Ideas such as these form part of an effort to transform ecological crises into points of departure for better-designed cities that integrate both humans and nonhumans into their cultural and economic values.

Artists, designers, and writers have all taken up these issues in their works. The 2010 MoMA exhibition Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront, curated by Barry Bergdoll, for example, focused on designs by artists and landscape architects that might protect Manhattan from rising sea levels and increasing storms due to climate change. Robert Graves and Didier Madoc-Jones’ Postcards from the Future, a series of speculative photo illustrations, reimagines London under conditions of large-scale migration and global warming. Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change(2011), a book by architect and New Urbanism founder Peter Calthorpe, explores models for sustainable urban futures. Three volumes by the feminist and environmentalist Rebecca Solnit that focus on San Francisco, New York, and New Orleans, respectively, combine maps and texts to highlight patterns of social, economic, cultural, and ecological change in the three cities now and in the future. And science fiction, from David Brin’s Earth(1990) to Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140(2017), has eagerly explored visions of future cities in their relationship to nature.

What will cities in 2099 look and feel like?

One of the challenges in creating such a brief portrait of urban nature eighty years into the future is finding the right combination of global and local dimensions of urbanization. On one hand, the urban problems and opportunities the story deals with need to be recognizable to current readers hailing from different continents and languages: challenges associated with, for example, pollution, access to green spaces, gentrification, real estate ownership and use, disease, disasters, energy and water infrastructures, and governance, among many others. On the other hand, these general problems that affect cities around the globe need to link up, in a narrative, with enough local specifics to capture readers’ interest in a particular scenario—whether the locale is real or imagined.

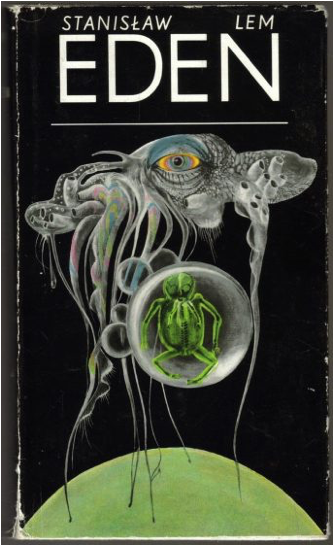

A second challenge concerns the combination of familiar and futuristic problems and solutions in the narrative. The portrayals of futuristic or alternative societies in speculative fiction and science fiction (terms that I will use interchangeably here so as to avoid delving into a debate of several decades’ standing about their identity or difference) need to contain enough familiar elements that they are still at least partially intelligible to readers. (The Polish science fiction writer Stanislav Lem, in his novels Eden[1958] and Solaris[1961], has eloquently thematized the enormous challenges that arise when humans traveling into outer space encounter planets and cultures that they have absolutely no grounds for understanding.) But stories about the future also usually contain what the science fiction scholar Darko Suvin has called the “novum”, the new element that turns a familiar scenario into one that does not quite map on to our present reality and thereby makes us look at our present in a new and different way. In this vein, Jonathan Lethem’s Gun, with Occasional Music(1994) and Sheri S. Tepper’s The Family Tree(1997) feature intelligent animals—descendants of animals used in biotechnological experiments in the twentieth century who are full members of future societies—as a way of making readers think in new ways about humans’ current relationships to nonhuman species.

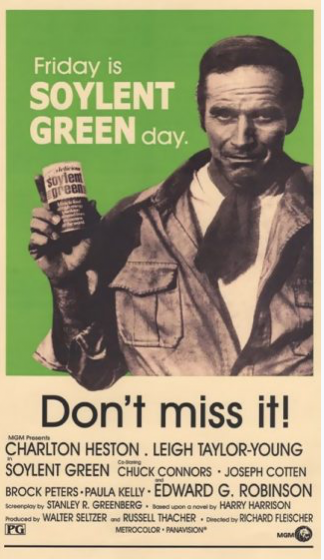

The literary scholar Fredric Jameson has put this in a somewhat different way by focusing on the typical time structure of futuristic texts. Science fiction makes us think critically about the present, he argues, by offering us a future in relation to which we have to re-envision our present as a past, the precursor to what the narrative portrays for us. This is, quite obviously, the principle of “cautionary tales” about the future, stories about societies that are considerably worse than our own or even dystopian. Descriptions of future totalitarian societies, dire scarcities, or ecological disasters in fiction and film—from Soylent Green (1973) to The Day after Tomorrow (2004)—are often meant to call on readers or viewers to beware of undemocratic, exploitative, or anti-environmental trends in the present.

Science fiction makes us think critically about the present, he argues, by offering us a future in relation to which we have to re-envision our present as a past…

The dystopian vision of the future was appropriated by writers interested in new media technologies as well as by environmentalists in the 1950s and 1960s. Kurt Vonnegut’s short story “EPICAC” (1950) and D.F. Jones’ novel Colossus(1960) foresaw computers taking over humans’ most personal relationships as well as world government. Rachel Carson adopted the dystopian genre to introduce her path-breaking book Silent Spring(1962) with a “A Fable for Tomorrow” that warned of a ghastly end to the agricultural heartland of America if the use of pesticides were continued, a vision that Brian Aldiss developed at a more global level in his science fiction novel Earthworks (1965). Paul Ehrlich similarly interpolated dystopian science fiction vignettes between the expository chapters of his nonfiction book The Population Bomb(1968), which warned of future starvation and misery if 1960s population growth rates continued into the future. A similar vision informed Harry Harrison’s Make Room! Make Room! (1966), which inspired the film Soylent Green, a vision that was shared by many other overpopulation fictions and films at the time. Implicitly or explicitly, dystopia continued to function as a tool for political criticism in these environmentalist works.

Over the last few decades, dystopian visions of the future have become standard in futuristic fiction and film. Fears about the loss of privacy and freedom in the digital age, about the consequences of biotechnology, the displacement of state by corporate power, aggravation of social inequality and economic exploitation, and about ecological catastrophe have resonated in texts as diverse as Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash(1992), Edmundo Paz Soldán’s El delirio de Turing (Turing’s Delirium, 2006), Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy (2003-2013), Rosaura Sánchez and Beatrice Pita’s Lunar Braceros 2125-2148 (2009), Efe Okogu’s “Proposition 23” (2012), Hao Jingfang’s “Folding Beijing” (2012), and Dave Eggers’ The Circle(2013), as well as in films such as Roland Emmerich’s 2012 (2009), Tarik Saleh’s Metropia (2009), and Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium(2013). Young adult novels and films such as The Hunger Games(2008-2010) and Divergent(2011-2013) series similarly portray socially and ecologically devastated futures. If the dominant mode in science fiction is to be believed, post-apocalyptic wastelands will be as ordinary as parking lots, anarchy as predictable as taxes, and cannibalism as common as lunch at McDonald’s.

Cities are often central to such dystopian visions. The metropolis has, of course, functioned as the quintessential place where modernity unfolds in many twentieth- and twenty-first-century works of speculative fiction—as well as in many other forms of contemporary art and literature. It is often presented as a material manifestation of societies to come, in both their best and their worst dimensions—from the latest achievements in commerce, communication, and transportation to the worst excesses of squalor, inequality, and oppression. Utopian views of cities have become rare in science fiction in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, though they do still emerge occasionally. Kim Stanley Robinson’s descriptions of New York City in his novels 2312(2012) and New York 2140, for example, foreground the ingenious ways in which New Yorkers have recreated their city after climate change and sea level rise, transforming it into a latter-day version of Venice. Both novels show how what seems to a twenty-first century reader like one of the most artificial and human-dominated environments on the planet can appear as an exhilaratingly natural habitat to off-worlders used to living in sealed-off domes, with the outside accessible only in spacesuits.

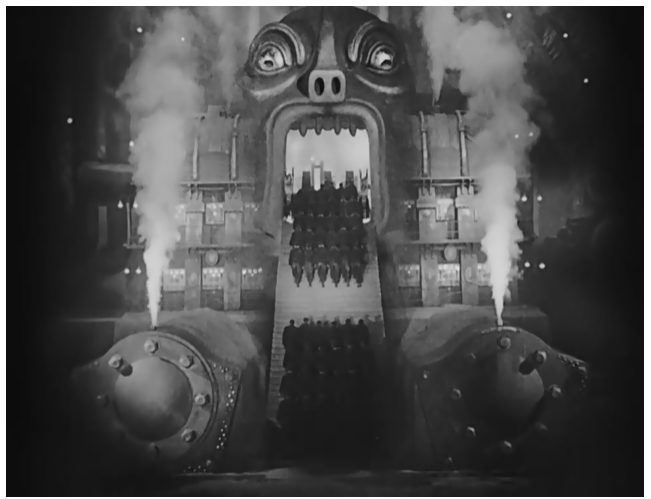

Dystopian views of cities make up the overwhelming majority of futuristic urban literature and film. The nightmarish social inequality of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis(1929) has found echoes in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and Neill Blomkamp’sElysium (2013), all films in which poverty and wealth are made visible through spatial segregation—to the point where in Blade Runner and Elysium, the wealthy migrate off planet, leaving contaminated and impoverished cities behind on Earth. In recent novelistic dystopias such as Eden Lepucki’s California(2014) or Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus(2015), the city is what the protagonists need to leave behind to escape the worst consequences of social and environmental collapse. And in the most extreme story pattern, a science fiction narrative that is by now over a hundred years old, charismatic metropolises need to be reduced to ashes and rubble before a new social order can emerge. In a by now classic essay called “The Literary Destruction of Los Angeles”, Mike Davis, surveying the films and fictions up to the mid-1980s, blamed the persistence of this narrative template on underlying racism. Visions of London, New York, or Los Angeles destroyed, he argued, fulfilled a racist white fantasy of getting rid of the multiracial and multicultural urban masses. In more recent scenarios of wholesale urban destruction, the fantasy arguably addresses a much broader desire to see modern society with its track record of complexity, inequality, and environmental damage erased in favor of simpler, more egalitarian, and more sustainable ways of life. Often, these post-apocalyptic returns to life without the modern city amount to futuristic visions of the pastoral: from the utopian village community in Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time(1976) to Howard Kunstler’s World Made by Hand(2008) and Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam(2013), the life of the future takes place outside the city.

Dystopian scenarios also appeared in the submissions to The Stories of the Nature of Citiescontest, for example in the highly surveilled and controlled cities of Tatiana Shashkova’s “June Bugs in Glass Jars” and Louise Nzomo’s “Escape from the Butterfly Apartments”, or in Tasha Kerry Smith’s “City of the Last Breath”, where those who cannot afford living in luxury compounds are shipped off to work in submarine settlements while drugs slowly kill them. Daniel Uncapher’s “Dandelion and the Floodshark”, meanwhile, approaches dystopia and apocalypse in an ironic vein in the manner of British novelist China Miéville. Many other entries also foreground the persistence of economic inequality and racial discrimination, and they engage seriously with misguided uses of technology, environmental risk, and degraded nature, showing how these problems may continue and even become aggravated in the future. But a great number of stories present far more optimistic visions of urban futures. Quite a few of them show ways in which future urban societies have adapted to changed ecologies and worked to address if not to eliminate the gaps between the rich and the poor.

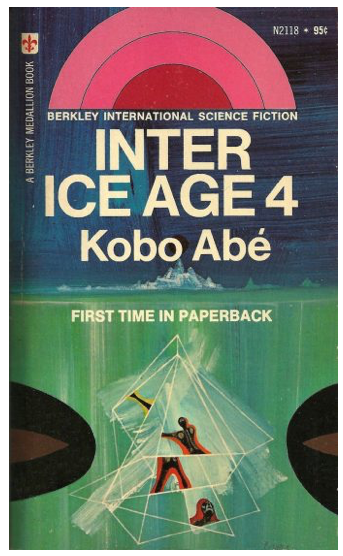

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the recurring theme of the flooded city. The city sinking beneath the waves is an age-old trope of speculative literature that one can trace all the way back to Plato’s Atlantis. In the twentieth century, it features prominently in hundreds of speculative fictions from Kobo Abe’s Inter Ice Age Four (第四間氷期, Dai-Yon Kampyōki[1959]), J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World (1962), and Sakyo Komatsu’s Japan Sinks(日本沈没, Nihon Chinbotsu[1973]) to recent novels such as Frank Schätzing’s Der Schwarm(The Swarm, 2004), Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl(2009), and Megan Hunter’s The End We Start From (2017). Since the turn of the millennium, the drowned city has increasingly come to be associated with climate change and rising sea levels, ecological processes that have given an old literary theme a new contemporary resonance.

Many of the fictions in A Flash of Silver-Green: The Stories of the Nature of Citiesallude to global warming or even focus on it as their central theme. But not all of them envision it according to the familiar story template of the disaster movie—the end-of-the-world catastrophe that only a select few survive, often centrally featuring a nuclear family with a heroic father figure. Instead, Alyssa Eckles’s “Uolo and the Idol” imagines a drowned city where piles of rusting cars have become habitat for new coral reefs and a vibrant marine biodiversity that has replaced agriculture as a food source for the human inhabitants. Claire Miye Stanford’s “Neither Above Nor Below” focuses on one of the currently most precarious cities, the Indonesian capital of Jakarta, which is threatened both by the soil subsidence that has followed from decades of aquifer depletion and by rising sea levels. In Stanford’s vision, Jakarta 2099 is “the only city in the world that had found a way to coexist with the rising tides”, a latter-day Venice that has become a global model by letting the water in and creating an entirely new environment for humans and nonhumans. In stories such as these, the drowning city as the melancholy icon of a civilization’s end morphs into a symbol of hope and a new urban way of living in and with nature.

This hopeful vision also predominates in stories that envision future cities as multispecies environments that encourage new bonds between humans and nonhuman species. In Elizabeth Twist’s “May Apple”, this takes the form of rituals that initiate city dwellers into the care of a particular plant, while in L.H. Metzger’s “Ecology” similar scientific attention to individual plants has led to an abundantly fertile and verdant urban landscape. In Amanda White’s “Listen”, biotranslators allow plants and ants, wolves, and worms to make their voices heard in meetings where humans discuss the future of the city. Mariusz Loszakiewicz’s “Tree” envisions cities that grow in trees, and that even the most recent technology is produced by tree growth.And in Joanne Bristol’s lyrical meditation “from eaves to footfall”, the boundaries between human and nonhuman, city and nature become so fluid that one often cannot be told from the other. Stories such as these see ecological crisis as a gateway to a new awareness and a new attribution of value—both cultural and economic—to the natural world and nonhuman species.

…who gets to benefit from nature and who does not, and who is exposed to ecological risks and who is not.

But Arakali’s, Lakshminarayan’s and Towey’s stories also highlight the underside of this renewed appreciation of green spaces: the gentrification of nature that makes access to parks a prerogative for the elite or only a temporary respite from landscapes that otherwise offer few experiences of plants and animals. In this vein, Sierra Adler’s “The Cathedral” features a domed park, from which the protagonist inevitably has to return to “normal” urban life without nature. Jenni Juvonen takes this scenario one step further in her story “Where Grass Grows Greener” by making the experience of “pure, authentic nature” one that is best accessed through virtual reality and by those who can afford its exorbitant cost. And Ari Honarvar’s “A Child of the Oasis” portrays a futuristic eco-utopian Paris only to highlight that the city is blocked to most of the desperate migrants fleeing from other regions of a planet in crisis. Stories such as these put questions about urban nature in 2099 firmly into the context of environmental justice, the question of who gets to benefit from nature and who does not, and who is exposed to ecological risks and who is not.

The contributors to this volume, then, reflect on a wide range of urban issues, from socioeconomic inequality, energy, water, transportation, and architecture all the way to population control, species extinction, and climate change. They offer vibrant visions of future cities, from tightly surveilled dystopias to urban eco-topias, sometimes democratically open and sometimes oligarchically closed. As the best writers to have emerged from this contest, their stories link their reflections on a particular locale and specific individuals to global urban and ecological processes and crises. In the process, the city often comes to function as a microcosm of planet Earth, challenging readers to imagine both the enormous heterogeneity and the unifying issues and institutions that shape planet-spanning societies. By offering a wide spectrum of visions of what urban futures at the end of the twenty-first century might look like, the stories collected here provide a vibrant inspiration to reimagine our cities even and especially in the face of the radical ecological changes that the twenty-first century has already begun to face.

Ursula Heise

Los Angeles

On The Nature of Cities

Also published by our partner, ArtsEverywhere.ca

Banner art by Katrine Claassens

References

Abbott, Carl. 2016. Imagining Urban Futures: Cities in Science Fiction and What We Might Learn from Them.Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Bergdoll, Barry, Michael Oppenheimer, Guy Nordenson, and Judith Rodin. 2011. Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront.New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Calthorpe, Peter. 2011. Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Carson, Rachel. 2002 [1962]. Silent Spring. New York: Houghton Mifflin. 40th anniversary edition.

Davis, Mike. 1998. Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster. New York: Henry Holt.

—. 2006. Planet of Slums.London: Verso.

Ehrlich, Paul. 1968. The Population Bomb. Cutchogue: Buccaneer.

Heise, Ursula K. 2008. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jameson, Fredric. 2005. Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. London: Verso.

Lee, Kai N., William R. Freudenburg, and Richard B. Howarth. 2013. Humans in the Landscape: An Introduction to Environmental Studies. New York: Norton.

Solnit, Rebecca. 2010. Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas.Oakland: University of California Press.

—. 2013. Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas. Oakland: University of California Press.

—. 2016. Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas. Oakland: University of California Press.

Suvin, Darko. 2016 [1979]. Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre. Ed. Gerry Canavan. Bern: Peter Lang. New edition.

UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs), Population Division. 2008. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2007 Revision. New York: United Nations. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wup2007/2007WUP_Highlights_web.pdf.

UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund). 2007. State of World Population 2007: Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth. New York: United Nations Population Fund. http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2007.

UN-Habitat (United Nations Human Settlement Programme). 2007. The State of the World’s Cities Report 2006/2007: Thirty Years of Shaping the Habitat Agenda. London: Earthscan for UNHabitat. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/11292101_alt.pdf.

Wolch, Jennifer. “Zoöpolis.” 1998. Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature-Culture Borderlands. Ed. Jennifer Wolch and Jody Emel. London: Verso, 1998. 119-138.

Leave a Reply